The impact of hysterectomy for benign conditions on patients’ life – our experience

Impactul histerectomiei pentru patologia benignă asupra calităţii vieţii pacientelor – experienţa noastră

Abstract

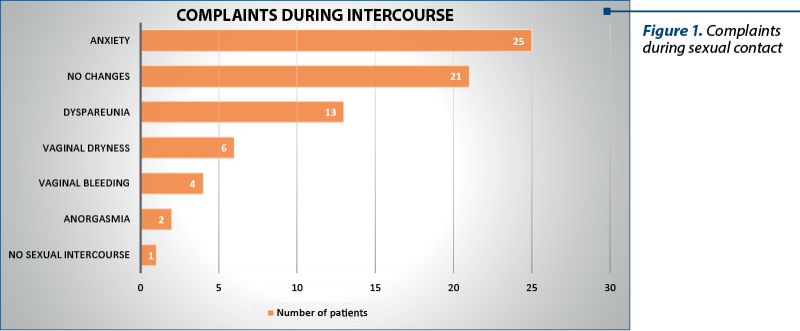

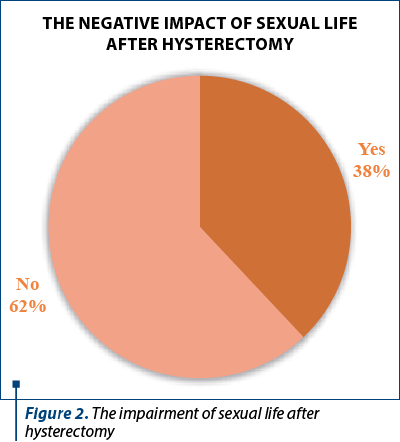

Introduction. Sexual life has a major importance in a woman’s life during premenopause and beyond. Hysterectomy for benign conditions is a frequent surgical intervention in gynecology, indicated for benign reasons. That can cause various issues regarding physical and psychological well-being, both physical and psychological. Materials and method. In our study, we chose 50 patients who had total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy in a period of one year. They were interviewed using a telephone questionnaire, which included questions about the sexual life before and after the operation. Results. The study revealed preoperative symptoms such as metrorrhagia (43%), menorrhagia (39%), pelvic-abdominal pain (24%), secondary anemia (20%) and other related symptoms (2%). After the surgery, the sexual life was affected, and the patients complained about anxiety in 25% of cases, pain during sexual contact (13%), vaginal dryness (6%), bleeding during or after sexual contact (4%) and anorgasmia (2%). However, most of the patients declared that their sex life was not affected after the surgical intervention (62%), while the rest (38%) answered affirmatively. Conclusions. The low quality of sexual life can lead to changes in behavior, in the perception of her own body, to lower self-esteem and subsequently to a lower quality of life, but this is not significantly affected by hysterectomy.Keywords

hysterectomyquality of sexual lifedyspareuniapelvic painRezumat

Introducere. Viaţa sexuală are o importanţă majoră în viaţa unei femei, în timpul premenopauzei şi ulterior. Histerectomia este o intervenţie chirurgicală frecventă în ginecologie. Aceasta poate determina diverse efecte, atât fizice, cât şi psihologice. Materiale şi metodă. În studiul nostru, am ales 50 de paciente de vârstă medie care au avut histerectomie totală cu anexectomie bilaterală. Acestea au răspuns unui chestionar telefonic, care a inclus întrebări despre viaţa sexuală înainte şi după operaţie. Rezultate. Studiul a relevat simptome preoperatorii, cum ar fi metroragie (43%), menoragie (39%), durere pelviano-abdominală (24%), anemie secundară (20%) şi alte simptome asociate (2%). După intervenţia chirurgicală, viaţa sexuală a fost afectată, astfel că pacientele au descris anxietate în 25% din cazuri, dispareunie în 13% din cazuri, uscăciune vaginală (6%), sângerări în timpul sau după contactul sexual (4%) şi lipsa orgasmului (2%). Cu toate acestea, majoritatea pacientelor au afirmat că viaţa lor sexuală nu a fost semnificativ afectată după intervenţia chirurgicală (62%), în timp ce restul (38%) au răspuns afirmativ. Concluzii. Afectarea vieţii sexuale poate duce la schimbări în comportament, în percepţia propriului corp, la scăderea stimei de sine şi, ulterior, la o calitate mai scăzută a vieţii, dar nu este influenţată semnificativ de histerectomie.Cuvinte Cheie

histerectomiecalitatea vieţii sexualedispareuniedurere pelvianăIntroduction

Hysterectomy is one of the most common surgical interventions in the gynecological field. Its indications include benign causes such as uterine fibromatosis, dysmenorrhea, metrorrhagia etc.(1) The surgical intervention can be total or subtotal, with or without unilateral or bilateral adnexectomy, which also involves the removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes together with the removal of the uterus(2). In this study, we talk about total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy performed for benign conditions.

The surgical method can include abdominal, laparoscopic or vaginal approach, each one with different complications, depending on the technique, the operator’s experience and the comorbidities of the patients(1).

Hysterectomy is nowadays an intensely debated surgical operation, which causes concerns among patients and professional communities due to the postoperative potential damage to the quality of life, implicitly to sexual function(3). Sexual life is an important part in a woman’s life. The associated sexual dysfunction is believed to be produced by numerous secondary factors such as psychological ones that accompany both the surgical intervention itself and the postoperative recovery period. Cultural factors have a significant importance, because in many cultures the uterus is associated with femininity and reproduction through the role of women to give birth, therefore its extirpation would lead to the feeling of loss of femininity(3,4). The appetite for life lust can also undergo changes by altering the perception of the body, which seems to be incomplete after the operation(3-5).

According to a study, the attitude towards sexual activity may differ between eastern and western female populations. Moreover, sex is considered a taboo subject that some patients are shy to talk about in the presence of the doctor, that’s why sex education is fundamental(4). Another study claims that a poor sexual education leads to a decrease in the quality of intimate life. Local factors have a major impact on sex life due to surgically induced menopause and the related distressing symptoms(2,6).

This study aimed to evaluate the sexual activity and quality of sexual act, but also the sexual changes and the impairment of the postoperative sexual function.

Methodology

We performed a retrospective analytical observational study on a group of 50 patients from the “Bucur” Maternity Hospital, Bucharest, Romania. Patients who underwent total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy were evaluated over a period of one year.

The core tool of this study was represented by a telephone questionnaire. The patients were enrolled between July and August 2016. This questionnaire included 16 questions with both simple and multiple answers, leaving room for three questions with the possibility of personalized answer.

Contacted by phone, the patients agreed to be included in this research. The processing of personal data was carried out according to the legal norms, with the aim of respecting professional secrecy. The questionnaire included general data such as age, background, marital status, number of births, tobacco consumption, associated medical pathologies, previous surgical interventions, but also data targeted to the subject of the study, such as clinical manifestations present before hospitalization, surgical approach, postoperative complications, changes during sexual contact, and the evaluation of pleasure by intercourse before and after surgery.

The data collected after completing the questionnaire were processed with IBM SPSS.

The inclusion criteria were: patients in whom the physiological menopause did not occur before the surgical intervention, and patients who underwent hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy in the time interval 1.01.2019-31.12.2019.

The exclusion criteria were: patients who underwent surgery for malignant uterine pathology.

Results

From the point of view of the age group, the patients included in the study were in the fourth decade of age. After collecting the data, it was identified that the minimum age was 41 years old and the maximum age was 50 years old; thus, a percentage of 90% was represented by the subcategory 46-50 years old and the remaining 10% corresponded to the subcategory 40-45 years old. Marital status was also considered, and it was observed that 78% of women were married and 22% were divorced. Next, if we refer to the parity of the patient, 90% had 1-2 births, 8% had more than three births and 2% had no birth.

The living and working conditions revealed that the majority of them (70%) came from the urban environment, while 30% were from the rural environment. Regarding the tobacco consumption, there was a high percentage (62%) of non-smokers, and 38% of them were smokers. The importance of tobacco consumption is revealed by the increased incidence of fibromyomas in non-smokers, a pathology that also constitutes a frequent indication of total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy (HTAB).

Regarding the associated medical pathologies, the studied group included a variety of comorbidities, the most significant pathology being obesity, which represented a percentage of 31%. Other diseases were also noted, but with a lower percentage, such as arterial hypertension (15%), diabetes (13%), endocrinological conditions (11%), gastric pathology (6%) and viral hepatitis (4%). However, 20% did not present associated pathologies.

The associated surgical interventions revealed that almost a quarter (24%) of the subjects did not undergo any surgical intervention. Instead, the rest were occupied, with close percentages, by procedures such as history of appendectomy (20%), caesarean section (22%), curettage of any kind (20%) and other interventions not classified somewhere else (14%).

The clinical manifestations highlighted two frequently encountered complains, metrorrhagia (43%) and menorrhagia (39%). Other conditions that can be mentioned were pelvic-abdominal pain (24%), secondary anemia (20%) and other symptoms (2%). As a consequence, total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy was indicated, and the abdominal approach was chosen in 94% of cases. The laparoscopic approach was used in a minority of 6% of patients. The vaginal approach is usually not indicated due to the fact that it does not offer optimal visualization and manipulation of the organs and to the lack of experience in our settings.

In order to determine how HTAB influenced the sexual life, the patients were asked a series of targeted questions about pre- and postoperative sexual life. From the point of view of sexual activity, the majority of 70% were sexually active, followed by a category of 24% less active, and a minority of 6% without constant sexual activity.

Postoperatively, the subjects were asked if they felt changes during sexual intercourse. The patients who had sexual activity declared that they experienced multiple changes, such as anxiety in 25% of cases, dyspareunia (13%), vaginal dryness (6%), bleeding during or after sexual contact (4%) and lack of orgasm (2%). On the opposite side, there were 21% of patients who had no complains – they have not undergone changes, and more than 1% did not have sexual contact (Figure 1).

Pleasure during sexual intercourse was subjectively evaluated both pre- and postoperatively. Before the surgical intervention, 90% of women enjoyed sexual contact, while 8% had a moderate pleasure and, unfortunately, the rest had a satisfactory experience. After surgery it can be observed that in 52% of cases the pleasure during the act was not changed, while 40% described an experience of moderate intensity, and the remaining 8% reported no satisfaction related to sexual activity.

Thus, most of the patients subjected to the study did not think that their sex life was affected after the surgical intervention (62%), while the rest (38%) answered affirmatively, reporting that anxiety was the main reason why their sex life underwent unpleasant changes (Figure 2).

Discussion

Our study shows that the sex life after hysterectomy did not significantly change, even though some patients who described relative pain during sexual contact felt an improvement postoperatively.

At the same time, there were postoperative changes in sexual activity due to the psychological concerns manifested by anxiety, but also physical damage, by the effects caused by surgically induced menopause through bilateral adnexectomy, which is manifested by complaints such as dyspareunia, vaginal bleeding, vaginal dryness or anorgasmia. Not least, the surgical approach plays an important role in affecting the sexual life after hysterectomy in terms of the side effects related to each approach.

An observational study published in December 2020 by Beyan et al., conducted on a group of 455 patients undergoing hysterectomy for benign causes, claims that sex life and the quality of life improve postoperatively. As a result, the preoperative clinical manifestations, such as vaginal bleeding, chronic abdominal-pelvic pain or dyspareunia, which affected the patients’ personal life and prevented them from feeling pleasure during sexual contact, are gone(1,3,7-9).

Other studies proved that preoperative dysmenorrhea would represent a predictive factor for postoperative sexuality, because with the surgical intervention this symptom also disappears, and this is another fact that leads to the improvement of sexual function(10).

In addition to other studies, it’s been shown that the chosen surgical approach has a significant impact on the resumption of sexual function due to possible postoperative side effects and complications(3,11). That’s why the surgical approaches were compared and it was demonstrated that the laparoscopic approach is recommended over the open one, due to shorter recovery time, lower risk of complications, faster reintegration and social adaptation(3,11,12). However, several cases of severe complications due to vaginal cuff dehiscence after laparoscopic hysterectomy were reported in the literature(13,14).

In the situation that the patients from our group were mostly subjected to the open abdominal approach, it could be a susceptibility to slower resumption and difficult readaptation to postoperative sexual life.

On the other hand, some other authors demonstrated that the surgical approach has no importance in the sexual function after hysterectomy(15-17).

Another analytical study conducted in 2020 by Afiyah et al., in three cities from Indonesia, on a group of 103 women with total hysterectomies, revealed the psychological problems involved in the postoperative quality of life(18). Some of the patients suffered from a decreased self-esteem caused by postoperative sexual dysfunction, because intercourse is not recommended during the six-week recovery period and the personal life of the subjects would have suffered(19). Thus, the study showed that there is a causal relationship between the convalescence period and lower sexual function. However, the quality of life after surgery seems to be positively influenced by the interpersonal relationships and support of family and friends. Emphasis is also placed on the importance of the medical care provided, on sex education programs, prevention and preoperative counseling, which should include a broad discussion about the recovery period, possible complications, risks, negative postoperative effects and their therapy, in order to make the critical period a pleasant one(2,20-24).

In 2008, Yen et al. published a prospective study in which they evaluated the psychological impact and the risk of developing mental disorders in a group of 68 post-hysterectomy subjects. The patients included in research described preoperative depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, distortion of body images and sexual dysfunction, based on the fact that the surgical removal of the uterus and ovaries would lead to a decrease in femininity and vitality(4,25).

Moreover, other studies support the correlation between the preexistence of a psychiatric pathology such as depression or unsatisfactory sex life and the alteration of postoperative sexual functions(11,16). On the other hand, a clinical study by Helström et al. shows that the preexisting psychiatric pathologies do not play a role in sexuality before and after surgery(10).

Like any other surgical intervention, hysterectomy is not devoid of negative effects. For instance, by removing the cervix, the uterovaginal plexus can be damaged, which can have an unpleasant effect on lubrication and on achieving orgasm(4). Among other modified local factors, the reduction of cervical mucus is also listed.

Other authors also refer to a significant deterioration of the thermal sensitivity of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, even though vibratory vaginal and clitoral sensitivity were maintained pre- and postoperatively(26). Another article mentioned a small percentage of patients with reluctance to achieve orgasm, even though the majority of patients enjoy it after surgery(25).

Also, the bilateral adnexectomy performed on premenopausal patients leads to climacteric manifestations such as vaginal dryness, friable vaginal mucosa, vaginal bleeding and decreased libido due to estrogen deficiency(4,16,24). All these factors can negatively influence both the quality of life and sexual function(27).

Even though some authors claim that this negative effect could be combated, another study questions the effectiveness of hormone replacement treatment in post-hysterectomy patients and shows that the changes caused by estrogen deficiency would not be reversible with the help of therapy(16,28). Moreover, Kuscu et al. claim that the presence or absence of menopause does not determine any difference according to the lower sexual appetite in the postoperative period(29).

Our study highlights once again the changes that occurred after hysterectomy, namely anxiety in 25% of cases, dyspareunia (13%), vaginal dryness (6%), bleeding during or after sexual contact (4%) and anorgasmia (2%).

In addition to psychological and local gynecological factors, cultural factors have a major impact. In the study published by Yen et al.(4), it has been shown that hysterectomy causes women to feel de-feminized, because they believe that the role of a woman is to be a birth giver. So, the removal of the uterus will prevent them to carry a pregnancy.

Moreover, the patients feel reluctant and even embarrassed to discuss about their sexual life. According to the study mentioned before, only 21% had the courage to initiate a discussion about sexual dysfunction and then even ask for specialized help. As a result, many cases of postoperative sexual dysfunction remain unresolved. That is why it is recommended to strengthen a good doctor-patient relationship that allows to discuss intimate issues(24).

The results of the retrospective study conducted by Doğanay et al. in Turkey revealed postoperative changes. It has been demonstrated that bilateral adnexectomy performed before menopause causes mostly negative effects that are reflected on sexual life, namely dyspareunia, decreased libido and anorgasmia. However, the authors claim that hysterectomy positively affects sexual function(30).

The same conclusion was reached by Thakar in 2015, who published a study about local postoperative changes that could appear after a longer period of time as an aging effect, being probably part of physiological changes, and thus the surgical intervention would improve the sexual function or maintain it the same(6). However, a certain level of sexual dysfunction can, unfortunately, be found in a significant percentage of women both in pre- and postmenopause(5).

A study by Peterson et al. claims that dyspareunia and anorgasmia are late effects whose frequency increases directly proportional to the period of time passed after the surgical intervention(31).

Finally, the negative effects could be attributed to both psychological and physical factors through changes in the rapports of the pelvic organs, damage to the local innervation and vascularization(1,6,7,11,26).

The research presented by us shows – like other studies presented before – that the sexual life of women after hysterectomy remained at least constant or even changed in a pleasant way(17,32). In contrast, the number of women who have pleasure of moderate intensity increased, surprisingly, from 8% preoperatively to 40% postoperatively. At the opposite side, there are the patients who cannot relate a pleasant experience during intercourse, whose percentage, unfortunately, increased from 2% to 8%.

As it can be seen, the sex life of patients undergoing hysterectomy for benign causes does not bring more pleasure to already satisfied patients, but on the contrary, the surgery affects their sex life, probably for the psychological, physical and/or social reasons mentioned before(25). Also, we can say that local postoperative symptoms such as dyspareunia, anorgasmia and vaginal dryness that can lead to vaginal bleeding, along with the anxiety caused by surgery and by the postoperative period of reintegration of sexual function, but also the surgical approach and the possible postoperative complications can lead to a decrease of the quality of sexual life.

On the other hand, for patients who declare an acceptable sexual life, the quality of pleasure seems to improve postoperatively, most likely due to the elimination of the past clinical manifestations. The quality of life in this category is much lower preoperatively, because of all the changes that have significantly affected the quality of life over time. Moreover, the increase in the number of women who have an acceptable sex life can, unfortunately, be based on the transformation of an intense pleasure expressed preoperatively into a pleasant event.

Last but not least, attention must be drawn to cultural reasons, which in the case of a poor doctor-patient relationship can determine the maintenance of long-term side effects. Physicians must have an approach as open as possible to the patient, so that some consequences caused by adnexectomy – i.e., menopause symptoms and others – be corrected through medical therapy.

Regarding the cultural reasons, some studies have revealed that, with the help of psychological counseling, the patients could overcome all the guilt and dishonor they feel postoperatively, in order to increase the quality of life and the perception of their own femininity(20).

To conclude, post-hysterectomy sex life has improved or remained the same for women undergoing surgery. In this situation, several factors are incriminated, such as physical, psychological, cultural and social, each one of them reflecting its power on the quality of women’s sexual life(33). The limitations of this study consist in the variable periods of time that have passed since the surgical procedure.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that the impairment of sexual function depends on the perception of pleasure of each group of patients, namely those who are satisfied, content or dissatisfied, with a background of anxiety determined by the surgical intervention.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Martínez-Cayuelas L, Sarrió-Sanz P, Palazón-Bru A, Verdú-Verdú L, López-López A, Gil-Guillén VF, Romero-Maroto J, Gómez-Pérez L. A systematic review of clinical trials assessing sexuality in hysterectomized patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 202110;18(8):3994.

-

Panahi R, Anbari M, Javanmardi E, Ghoozlu KJ, Dehghankar L. The effect of women’s sexual functioning on quality of their sexual life. J Prev Med Hyg. 2021;62(3):E776-E781.

-

Beyan E, İnan AH, Emirdar V, Budak A, Tutar SO, Kanmaz AG. Comparison of the effects of total laparoscopic hysterectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy on sexual function and quality of life. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8247207.

-

Yen JY, Chen YH, Long CY, Chang Y, Yen CF, Chen CC, Ko CH. Risk factors for major depressive disorder and the psychological impact of hysterectomy: a prospective investigation. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):137-42.

-

Ambler DR, Bieber EJ, Diamond MP. Sexual function in elderly women: a review of current literature. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2012;5(1):16-27.

-

Thakar R. Is the uterus a sexual organ? Sexual function following hysterectomy. Sex Med Rev. 2015;3(4):264-278.

-

Maas CP, Weijenborg PT, ter Kuile MM. The effect of hysterectomy on sexual functioning. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2003;14:83-113.

-

Wydra D, Ciach K, Sawicki S, Emerich J. Ocena zycia seksualnego po usunieciu macicy [Sexual life after hysterectomy]. Ginekol Pol. 2003;74(7):505-7.

-

Punushapai U, Khampitak K. Sexuality after total abdominal hysterectomy in Srinagarind Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89 Suppl 4:S112-7.

-

Helström L, Weiner E, Sörbom D, Bäckström T. Predictive value of psychiatric history, genital pain and menstrual symptoms for sexuality after hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73(7):575-80.

-

Wang Y, Ying X. Sexual function after total laparoscopic hysterectomy or transabdominal hysterectomy for benign uterine disorders: a retrospective cohort. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2020;53(3):e9058.

-

Kürek Eken M, İlhan G, Temizkan O, Çelik EE, Herkiloğlu D, Karateke A. The impact of abdominal and laparoscopic hysterectomies on women’s sexuality and psychological condition. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;13(4):196-202.

-

Nguyen ML, Kapoor M, Pradhan TS, Pua TL, Tedjarati SS. Two cases of post-coital vaginal cuff dehiscence with small bowel evisceration after robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(7):603-5.

-

Hada T, Andou M, Kanao H, Ota Y, Takaki Y, Kobayashi E, Nagase T, Fujiwara K. Vaginal cuff dehiscence after total laparoscopic hysterectomy: examination on 677 cases. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4(1):20-5.

-

Kayataş S, Özkaya E, Api M, Çıkman S, Gürbüz A, Eser A. Comparison of libido, Female Sexual Function Index, and Arizona scores in women who underwent laparoscopic or conventional abdominal hysterectomy. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;14(2):128-132.

-

Lonnée-Hoffmann R, Pinas I. Effects of hysterectomy on sexual function. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2014;6(4):244-51.

-

Roovers JP, Lakeman MM. Effects of genital prolapse surgery and hysterectomy on pelvic floor function. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2009;1(3):194-207.

-

Afiyah RK, Wahyuni CU, Prasetyo B, Dwi Winarno D. Recovery time period and quality of life after hysterectomy. J Public Health Res. 2020;9(2):1837.

-

Flory N, Bissonnette F, Binik YM. Psychosocial effects of hysterectomy: literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(3):117-29.

-

Danesh M, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Moosazadeh M, Shabani-Asrami F. The effect of hysterectomy on women’s sexual function: a narrative review. Med Arch. 2015;69(6):387-92.

-

Bradford A, Meston C. Sexual outcomes and satisfaction with hysterectomy: influence of patient education. J Sex Med. 2007;4(1):106-14.

-

Graesslin O, Martin-Morille C, Leguillier-Amour MC, Darnaud T, Gonzales N, Bancheri F, Levert M, Bory JP, Harika G, Gabriel R, Quereux C. Enquête régionale sur le retentissement psychique et sexuel à court terme de l’hystérectomie. Sexual functioning after the hysterectomy: results of a local investigation. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2002;30(6):474-82 [French].

-

Kuppermann M, Learman LA, Schembri M, Gregorich SE, Jackson R, Jacoby A, Lewis J, Washington AE. Predictors of hysterectomy use and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(3):543-51.

-

Raboch J, Boudník V, Raboch J Jr. Das Geschlechtsleben nach der Hysterektomie. [Sex life following hysterectomy]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1985;45(1):48-50 [German].

-

Eicher W. Zur Frage der sexuellen Funktion und sexueller Störungen nach Hysterektomie. [Sexual function and sexual disorders after hysterectomy]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1993;53(8):519-24 [German].

-

Lowenstein L, Yarnitsky D, Gruenwald I, Deutsch M, Sprecher E, Gedalia U, Vardi Y. Does hysterectomy affect genital sensation? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 20051;119(2):242-5.

-

Sözeri-Varma G, Kalkan-Oğuzhanoğlu N, Karadağ F, Ozdel O. The effect of hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy on sexual satisfaction. Climacteric. 2011;14(2):275-81.

-

Celik H, Gurates B, Yavuz A, Nurkalem C, Hanay F, Kavak B. The effect of hysterectomy and bilaterally salpingo-oophorectomy on sexual function in post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 2008;61(4):358-63.

-

Kuscu NK, Oruc S, Ceylan E, Eskicioglu F, Goker A, Caglar H. Sexual life following total abdominal hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271(3):218-21.

-

Doğanay M, Kokanalı D, Kokanalı MK, Cavkaytar S, Aksakal OS. Comparison of female sexual function in women who underwent abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(1):29-32.

-

Peterson ZD, Rothenberg JM, Bilbrey S, Heiman JR. Sexual functioning following elective hysterectomy: the role of surgical and psychosocial variables. J Sex Res. 2010;47(6):513-27.

-

Dragisic KG, Milad MP. Sexual functioning and patient expectations of sexual functioning after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1416-8.

-

Mokate T, Wright C, Mander T. Hysterectomy and sexual function. J Br Menopause Soc. 2006;12(4):153-7.