Septate uterus is more closely associated with infertility, recurrent abortion and obstetrical malpresentations. This pathology raises controversies regarding the optimization of diagnostic criteria and surgical indication. The purpose of this article is to perform a mini-review useful for clinicians about the diagnosis criteria using 2D and 3D ultrasound, hysteroscopy and hysterosalpingography. The myoma-like structure of the uterine septum contributes to the understanding of the clinical consequences and the technique of septum resection by hysteroscopy or abdominal metroplasty.

Uterul septat: mini-review util clinicienilor

The septate uterus: a mini-review useful for clinicians

First published: 16 martie 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.68.1.2020.3035

Abstract

Rezumat

Uterul septat se asociază în multe cazuri cu infertilitatea, avortul recurent şi cu prezentaţiile distocice. Această patologie ridică unele controverse privind optimizarea criteriilor de diagnostic sau indicaţiile de tratament chirurgical. Prin acest articol ne propunem să efectuăm un minireview util pentru clinician şi să prezentăm criteriile de diagnostic utilizând ecografia 2D şi 3D, histeroscopia şi histerosalpingografia. Structura septului uterin din ţesut muscular şi fibros „leiomiom-like” contribuie la înţelegerea consecinţelor în plan clinic şi a tehnicii histeroscopice de rezecţie a septului sau prin metroplastie abdominală.

First described in the 1800’s by Cruveillhier and Von Rokitansky, congenital malformations of the female reproductive system belong to a heterogeneous group of abnormalities associated with poor reproductive outcomes. Female genital tract anomalies have greater variability by comparison with male genital tract anomalies (which include hypospadias, bladder exstrophy, micropenis and megalourethra).

Normal embryonic and fetal development of the female reproductive system involves a series of complex processes. Sexual differentiation occurs after the 10th week of fetal development. The mesonephric urinary ducts are formed and connected at the caudal end with the urogenital sinus and the cloaca. Müller’s (paramesonephric) ducts develop lateral and parallel to the mesonephric ducts. The anterior or cranial portions of the paramesonephric duct system develop into the fallopian tubes; the middle portion evolves into the body of the uterus, while the caudal fused portions become the primordium of the cervix and the upper vagina(1). Therefore, uterine congenital anomalies are a consequence of the failure of fusion of the müllerian duct system.

Septate uterus appears following insufficient resorption of the tissue connecting the two paramesonephric ducts, prior to the 20th embryonic development week. A close embryologic relation has been proven between the development of the urinary and reproductive organs; although renal tract defects are more likely to be found in women with müllerian duct malformations, septate uteri are not necessarily associated with renal tract defects.

Genital tract abnormalities are generally asymptomatic in the general population. A septate uterus is usually discovered during evaluations for infertility, pelvic pain, recurrent miscarriages, or incidentally during routine ultrasound evaluation for pregnancy testing, during caesarean section intervention, laparoscopy, hysteroscopy or laparotomy. The reported prevalence of intrauterine abnormalities is about 2% to 7% of all infertile women, and about 5% to 30 % of women with personal history of repetitive abortion(2), and 9.8% in a general population-based study(3). The same authors demonstrate a statistically significant increased risk of abortion in the second trimester of pregnancy and fetal malpresentation in case of septate uterus(2). Approximately 6% of all women with recurrent miscarriages and 3.5% to 6.4% of all infertile women have a septate uterus(4), by comparison with 2% to 3% in the general female population.

A septate uterus may be associated with infertility, recurrent abortion and obstetrical malpresentations. This pathology raises controversy regarding the optimization of diagnostic criteria and surgical indication. The authors’ personal experience of 25 years confirms the association of uterine septum with pelvic presentation and premature birth, but there have been cases of septate uterus not diagnosed prenatally with term births, without obstetric complications. Also, in a non-communicated personal series, the authors noticed three cases of placenta with abnormal adherence, uterine rupture and respectively postpartum massive hemorrhage post-metroplasty performed systematically with no infertility history.

The septum may be partial or complete, including the uterine cervix. Both variations may be associated with a longitudinal vaginal septum.

Uterine anomalies have been classified since 1988 using the American Fertility Society (AFS) criteria (currently, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine; ASRM).

The AFS/ASRM classifications of adnexal adherences, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions(5):

-

Group 1 – hypoplasia/agenesis.

-

Group 2 – unicornuate.

-

Group 3 – didelphus uterus.

-

Group 4 – bicornuate uterus.

-

Group 5 – septate uterus.

-

Group 6 – arcuate uterus.

-

Group 7 – diethylstilbestrol-related anomalies.

Even so, there are multiple different classification systems of genital tract anomalies based on uterus anatomy and shape, clinical utility, including septate uterus, modern diagnosis tools (2D transvaginal ultrasonography [2D-TVS], 3D transvaginal ultrasonography [3D-TVS], 2D sonohysterography [2D-SIS] and 3D sonohysterography [3D-SIS]). There is also a classification of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/European Society for Gynecological Endoscopy (ESHRE/ ESGE) and the Congenital Uterine Malformation by Experts (CUME). Thirty years ago, the gold standard for the diagnosis of septate uterus and female congenital anomalies was combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy. The conventional methods for the assessment of uterine morphology are hysterosalpingography, 2D and 3D ultrasonography, hysterosonography, hysteroscopy and hysteroscopy combined with laparoscopy. Sometimes, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful for the uterine external contour and for inner ostia and inner cornual visualization. MRI is expensive and requires specialized training for uterine pathologies interpretation; however, MRI is a comparable tool with 3D expert ultrasound. The gold standard diagnostic tools represented by combined hysteroscopy and laparoscopy for uterine abnormality are becoming obsolete.

Criteria for the hysterosalpingographic

aspect of septate uterus

A divided uterus can be seen on hysterosalpingography (Figure 1). The clinician examines the shape and size of endometrial cavity; an angle of less than 75° between the uterine horns is suggestive of a septate uterus, while an angle of more than 105° is more likely suggestive of a bicornuate uterus. The accuracy of hysterosalpingography is only 55% in the differentiation between septate, arcuate, bicornuate or didelphic uterus(6).

Criteria for the ultrasound aspect

of septate uterus

Since the late 90s, 2D-TVS and 3D-TVS have become an important part of uterine malformation diagnosis imaging when interpreted by experts(7). Their sensitivity and specificity are reported to be close to 100% for diagnosing congenital uterine anomalies, comparable with those of magnetic resonance imaging(8) and when comparing with using laparoscopy-hysteroscopy. Ata et al. have demonstrated that 3D-TVS had a 100% agreement with MRI for diagnosing uterine septa, including measurements of septum length, septum width and septum-serosa distance(9).

On a 3D transabdominal coronal plan of the uterus on ultrasound, Salim et al.(10) diagnosed congenital uterine anomalies based on the 3D transabdominal measurements of the uterine cavity, such as width, fundal distortion and length of the unaffected uterine cavity in a coronal plan. The uterine cavity width is measured as the distance between the two internal tubal ostia; the fundal distortion is measured as the distance between the midpoint of the line adjoining the tubal ostia and the distal tip of fundal indentation or uterine septum; and the length of the unaffected uterine cavity is measured from the distal tip of the fundal indentation or uterine septum to the level of the internal ostium. Straight or convex fundal indentation and uniformly convex external contour are marks of a normal uterus. A concave fundal indentation with the central point of indentation at an obtuse angle (>90°) is characteristic for an arcuate uterus which represents a normal variant of uterus – not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes or infertility. All authors demonstrate the high accuracy of 3D ultrasonography in the differential diagnosis between septate and bicornuate uterus compared with hysteroscopy and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging.

Many studies compare 2D ultrasonography, 3D ultrasonography and hysterosalpingography for the assessment of uterine anatomy. 2D ultrasonography cannot clearly delimitate the intercornual or interostia distance; also, 2D ultrasonography and HSG are limited in delimitating the uterine fundus, making this exams inaccurate. All experts consider 3D ultrasonography the gold standard for the diagnosis of septate uterus(11-14). By visualizing the uterine septum which completely divides the uterine cavity from fundus to cervix, with external convex contour or indentation >10 mm, Ludwin et al. demonstrated that there is no significant difference in diagnostic value between 3D-TVS, 2D-SIS and 3D-SIS, or between expert 2D-TVS, 3D-TVS and 2D-SIS(15).

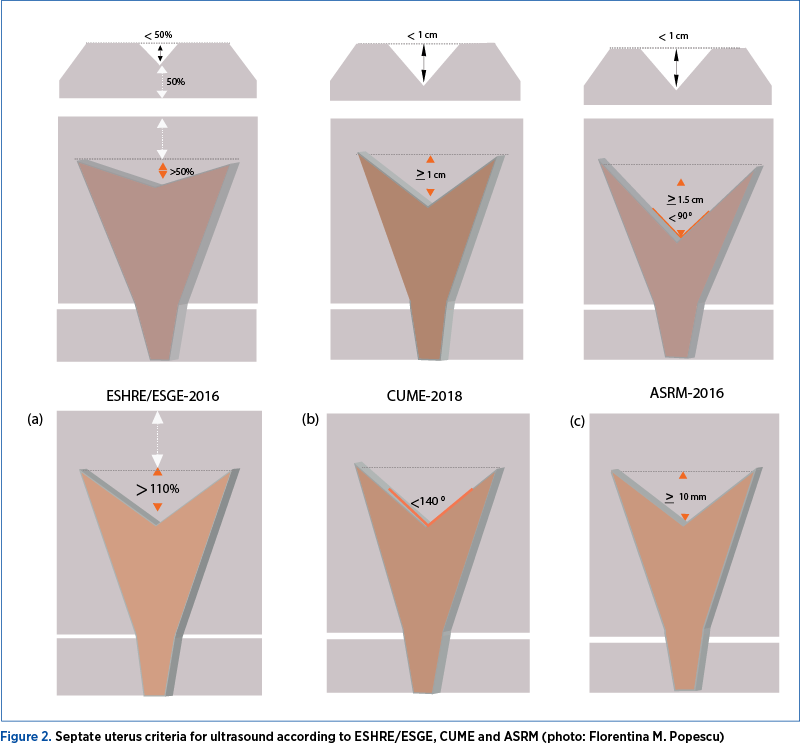

The optimal period to perform a 3D-US or a sonohysterography is between days 17 to 25 of the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle, when the endometrium becomes thicker and more echoic. For the ultrasound diagnosis of septate uterus, it is recommended to do a transverse, an axial and a coronal section of the uterus, and also to identify the shape of the endometrium and the fundus of the uterus. The following measurements are necessary to take into consideration for the diagnosis of septate uterus: the depth of the uterine fundus, the length of the body of the uterus, the angle of the indentation of the endometrium at the uterine fundus, and the uterine wall thickness. Figure 2 is adapted from different experts’ analyses(16-20): septate uterus measurements according to ESHRE/ESGE, ASRM and CUME definitions. Nowadays, the experts use rendered modes (VCI, OmniView with VCI or HDlive) for visualizing the 3D coronal view of the uterus.

Criteria for the hysteroscopic appearance

of septate uterus

Hysteroscopy allows both the direct visualization of the uterine cavity (ostia, septum and endometrium) and the operative metroplasty. However, the same as HSG, it cannot be used to evaluate the external contour of the uterus and the thickness of the myometrial fundus. In 2015, J.G. Smit et al. analyzed the reproducibility of hysteroscopic diagnosis of the septate uterus using standardized definitions for the hysteroscopic diagnosis of the septate uterus: the extent of the intracavitary development of septum, the angle formed by the central point of the indentation with the fundus, and the width of the bulging structure compared with the distance between both tubal orifices. These evaluations might increase the consensus among gynecologists in distinguishing between a normal, an arcuate and a septate uterus(21).

Structure of the uterine septum

In the late 80s, S. Khunda and Al-Juburi(22) observed that septum has a myoma-like structure. Thirty years latter, again, F.D. Fascilla and S. Bettocchi(23) analyzed the structure of the whole septum and reconfirmed the myoma-like structure of the uterine septum with variable thickening, characterized by muscle cells arranged in nodules of different sizes circumscribed by a thin septum of collagen fibers. Medium-sized vessels are distributed in the collagen fibers around the muscle cells and only a few capillary vessels are present in the muscular nodules. The septum extends to the anterior and posterior uterine wall, resembling a reverse “H” letter. The septum is covered by apparently functional endometrium with poor vascularization. The mechanisms behind the negative effect of the septum on fertility and pregnancy may also be represented by uncoordinated contractility of the septum with the whole uterus, by a local defect of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors in the endometrium covering the septal area(24,25). It seems that the implantation of the embryo at the level of the endometrial septum is accompanied by spontaneous abortion(26). In one study, Fedele et al. compared the structure of the endometrium of the intrauterine septum with the normal uterine wall and found a lower number of glandular cells with lower number of ciliated epithelial cells in the intrauterine septum(27). Fetal abnormal presentation, breech presentation and premature birth may occur due to reduced uterine capacity and uncoordinated uterine contractions, raising the question whether it is necessary to perform metroplasty before planning a pregnancy.

Surgical treatment

The surgical treatment of septate uterus is represented by hysteroscopic metroplasty. A previous 3D ultrasound is mandatory to differentiate septate uterus from bicornuate uterus and to measure the depth of the uterine fundus.

The National Institute of Health indicates metroplasty in case of septate uterus associated with infertility, personal history of abortion or preterm birth. An ongoing randomized trial initiated in 2009 has shown no benefit for systematically metroplasty use; the surgical correction may be followed by postsurgical complications and may unjustifiably increase health care costs(28).

Most studies have shown that septum resection helps increase the rate of pregnancies, of live and term births, and also contributes to an improvement in obstetric outcomes.

The abdominal metroplasty was first described by Strassman in 1907 (uterine incision near the uterine horns on both sides of the septum including myometrium and excision of a triangle formed by septum and part of the fundal uterine) and it was subsequently modified and simplified by Jones in 1953 (wedge excision of the septum), by Tompkins in 1962 (incision of the septum) and by Baghdad in 1984 (the removal of the septum centrally, preserving the fundus of the uterus for the reconstruction of the whole cavity). Until 2007, at the Bucharest “Filantropia” Hospital of Obstetrics and Gynecology, doctors had practiced the Tompkins procedure introduced by professor Aburel and his students. There are still case reports in literature about the surgical correction by abdominal metroplasty.

When indicated, the actual treatment of septate uterus is the hysteroscopic metroplasty, including the excision of the fibrous tissue from the uterus, like in the technique described by Betochi’s team(23), or sectioning of the septum with scissors or with mono or bipolar resectoscope or versapoint (franchise teams(29)), under ultrasound control in order not to pierce the uterus.

The resection is performed in the first part of the cycle (day 4 to day 9) using microscopes, resectoscope and argon laser therapy. What should be avoided is the dilatation of the cervix, recommending 5 mm operative resectoscopes.

The surgical metroplasty would increase the uterine cavity size and exclude the risk of egg implantation in the septum. The multicenter randomized study started in 2009 demonstrate the utility of surgical correction in women over 35 years old before pregnancy, rather than discovering it in patients after miscarriage(28).

A recent meta-analysis(30) compared the reproductive outcome after operative hysteroscopy for uterine septum using or not diathermy and demonstrated no statistically significant differences observed in reproductive outcomes (pregnancy rate, abortion, premature delivery rate) between women treated for septate uterus using resectoscope or scissors.

In conclusion, the septate uterus is a challenge for the gynecologist, the surgeon gynecologist, the fertility specialists and for obstetricians, due to controversies related to the diagnosis and the availability of surgical treatment. The septate uterus may be misdiagnosed in the general population and diagnosed after obstetrical complications or infertility. Often associated with hemorrhagic or incomplete resections, a consensus of the operative indications would be necessary in our country.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

2. Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Tan A, Thornton JG, Coomarasamy A, Raine-Fenning NJ. Reproductive outcomes in women with congenital uterine anomalies: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 38(4):371-82.

3. Dreisler E, Stampe Sørensen S. Müllerian duct anomalies diagnosed by saline contrast sonohysterography: prevalence in a general population. Fertil Steril. 2014; 102(2):525-9.

4. Jaslow CR. Uterine factors. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014; 41(1):57-86.

5. The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988; 49(6):944-55.

6. Steinkeler JA, Woodfield CA, Lazarus E, Hillstrom MM. Female infertility: a systematic approach to radiologic imaging and diagnosis. Radiographics. 2009; 29 (5): 1353-70.

7. Nicolini U, Bellotti M, Bonazzi B, Zamberletti D, Candiani GB. Can ultrasound be used to screen uterine malformations? Fertil Steril. 1987; 47(1):89-93.

8. Faivre E, Fernandez H, Deffieux X, Gervaise A, Frydman R, Levaillant JM. Accuracy of three-dimensional ultrasonography in differential diagnosis of septate and bicornuate uterus compared with office hysteroscopy and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012; 19(1):101-6.

9. Ata B, Nayot D, Nedelchev A, Reinhold C, Tulandi T. Do measurements of uterine septum using three-dimensional ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging agree? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014; 36(4):331-3.

10. Salim R, Woelfer B, Backos M, Regan L, Jurkovic D. Reproducibility of three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 21: 578–582.

11. Ludwin A, Martins WP, Nastri CO, Ludwin I, Coelho Neto MA, Leitao VM, et al. Congenital Uterine Malformation by Experts (CUME): better criteria for distinguishing between normal/arcuate and septate uterus? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 51: 101–9.

12. Grimbizis GF, Gordts S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Brucker S, De Angelis C, Gergolet M, et al. The ESHRE/ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Hum Reprod. 2013; 28: 2032–44.

13. Jurkovic D, Geipel A, Gruboeck K, Jauniaux E, Natucci R, Campbell S. Three-dimensional ultrasound for the assessment of uterine anatomy and detection of congenital anomalies: comparison with hysterosalpingography and two-dimensional ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995; 5: 233–7.

14. Raga F, Bonilla-Musoles F, Blanes J, Osborne NG. Congenital müllerian anomalies: diagnostic accuracy of three-dimensional ultrasound. Fertil Steril. 1996; 65: 523–8.

15. Ludwin A, Pityński K, Ludwin I, Banas T, Knafel A. Two- and 3D ultrasonography and sonohysterography versus hysteroscopy with laparoscopy in the differential diagnosis of septate, bicornuate, and arcuate uteri. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013; 20(1):90-9.

16. Ludwin A, Ludwin I, Coelho Neto MA, Nastri CO, Bhagavath B, et al. Septate uterus according to ESHRE/ESGE, ASRM and CUME definitions: association with infertility and miscarriage, cost and warnings for women and healthcare systems. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019; 10.1002/uog.2029.

17. Ludwin A, Ludwin I. Comparison of the ESHRE-ESGE and ASRM classifications of Mullerian duct anomalies in everyday practice. Hum Reprod. 2015; 30: 569–80.

18. Ludwin A, Martins WP, Nastri CO, Ludwin I, Coelho Neto MA, Leitao VM, et al. Congenital Uterine Malformation by Experts (CUME): better criteria for distinguishing between normal/arcuate and septate uterus? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 51: 101–9.

19. Grimbizis GF, Gordts S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Brucker S, De Angelis C, Gergolet M, et al. The ESHRE/ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Hum Reprod. 2013; 28: 2032–44.

20. Grimbizis GF, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saravelos SH, Gordts S, Exacoustos C, Van Schoubroeck D, et al. The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ESGE consensus on diagnosis of female genital anomalies. Hum Reprod. 2016; 31: 2–7.

21. Smit JG, Overdijkink S, Mol BW, Kasius JC, Torrance HL, Eijkemans MJ, et al. The impact of diagnostic criteria on the reproducibility of the hysteroscopic diagnosis of the septate uterus: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2015 Jun; 30(6):1323-30.

22. Khunda S, Al-Juburi A. Metroplasty – a new approach. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1988; 8:4, 343-4.

23. Fascilla FD, Resta L, Cannone R, De Palma D, Ceci OR, Loizzi V, et al. Resectoscopic metroplasty with uterine septum excision: a histologic analysis of the uterine septum. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019; 5. pii: S1553-4650(19)31334-2.

24. Raga F, Casañ EM, Bonilla-Musoles F. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in the endometrium of septate uterus. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1085-90.

25. Leible S, Munoz H, Walton R, Sabaj V, Cumsille F, Sepulveda W. Uterine artery blood flow velocity waveforms in pregnant women with mullerian duct anomaly: a biologic model for uteroplacental insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998; 178: 1048–53.

26. Grimbizis GF. The pathophysiology of septate uterus. BJOG. 2019; 10: 2020.

27. Fedele L, Bianchi S, Marchini M, Franchi D, Tozzi L, Dorta M. Ultrastructural aspects of endometrium in infertile women with septate uterus. Fertil Steril. 1996; 65:750–2.

28. Rikken JFW, Kowalik CR, Emanuel MH, Bongers MY, Spinder T, de Kruif JH, et al. The randomised uterine septum transsection trial (TRUST): design and protocol. BMC Womens Health. 2018; 5, 18(1):163. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0637-6.

29. Garbin O, Ziane A, Castaigne V, Rongières C. Do hysteroscopic metroplasties really improve really reproductive outcome? Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2006; 34(9):813-8.

30. Daniilidis A, Kalpatsanidis A, Kalkan U, Kasmas S, Pados G, Angioni S. Reproductive outcome after operative hysteroscopy for uterine septum: scissors or diathermy? Minerva Ginecol. 2020 Feb; 72(1):36-42. consecinţelor în plan clinic şi a tehnicii histeroscopice de rezecţie a septului sau prin metroplastie abdominală.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Managementul histeroscopic al subfertilităţii în cazurile cu suspiciune de polipi endometriali

Polipii endometriali reprezintă o afecţiune ginecologică benignă asociată cu sângerări uterine anormale, infertilitate şi pierderi repetate de sarc...