Uterine carcinosarcoma – case report

Carcinosarcom uterin – prezentare de caz

Abstract

Uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS) represents an extremely rare and aggressive gynecological neoplasm. This type of malignancy includes both carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements, and it carries a poor prognosis even when diagnosed at an early stage. The clinical features of UCS are similar to those of endometrial carcinoma. A 58-year-old menopausal female presented with severe pain and moderate vaginal bleeding for three weeks. The ultrasound examination described a thick endometrium (25 mm). The endometrial biopsy confirmed a moderate differentiated endometrioid carcinoma. The patient presented a remarkable rapid unfavorable evolution and underwent massive surgical resection. Postoperatively, immunohistochemistry of the specimen confirmed the uterine carcinosarcoma. Unfortunately, the patient was lost before starting any adjuvant therapy. The reported case presents a biphasic malignancy. It underlines the highly invasive nature of uterine carcinosarcoma and the extreme importance of the pathology findings.Keywords

uterine carcinosarcomasurgeryinvasiveRezumat

Carcinosarcomul uterin (CSU) este un neoplasm extrem de rar şi agresiv în sfera ginecologică. Acest tip de cancer include elemente de carcinom şi de sarcom, având un prognostic foarte rezervat, chiar şi dacă este diagnosticat precoce. Tabloul clinic este similar celui dat de carcinomul endometrial. Prezentăm cazul unei paciente în vârstă de 58 de ani, aflată în climax stabilizat. Aceasta s-a prezentat în serviciul de ginecologie cu dureri abdominale severe, însoţite de sângerare vaginală moderată, apărute de trei săptămâni. La examinarea ecografică a fost descris endometrul cu grosime anormală (25 mm). Biopsia endometrială a confirmat un carcinom endometrioid moderat diferenţiat. Pacienta a avut o evoluţie nefavorabilă foarte rapidă şi s-a practicat rezecţie chirurgicală extensivă. Postoperatoriu, examinarea imunohistochimică a specimenului a confirmat carcinosarcomul uterin. Din păcate, decesul s-a produs înainte de a începe terapia adjuvantă. Această prezentare de caz, care ilustrează un cancer bifazic, subliniază natura extrem de invazivă a carcinosarcomului uterin şi importanţa crucială a examenului histopatologic.Cuvinte Cheie

carcinosarcom uterinintervenţie chirurgicalăinvazieIntroduction

Uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS) – also called malignant mixed mesodermal tumor or malignant mixed Müllerian tumor – has been described as a high-grade non-differentiated endometrial cancer with carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements, both derived from a single malignant epithelial clone(1,2).

There are still many controversies about the unique nature of this lesion. Yet, all researchers agree that it is highly invasive and maintains a poor prognosis, even in early diagnosed and properly tailored managed cases(3). The low incidence and lack of preinvasive stage features prevent practitioners from screening for UCS(4). There are no prospective trials to establish protocols in early diagnosis and treatment, due to its rarity. This article presents our experience with a case of uterine carcinosarcoma in the County Emergency Clinical Hospital of Craiova, Romania.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with complaints of moderate vaginal bleeding and intense pelvic pain for three weeks. The patient was menopausal for three years. Unfortunately, she had no recent gynecologic exam. She had an unremarkable obstetrical history (two vaginal deliveries). She never used contraceptive pills. She denied any previous medical or surgical pathology and any recent history of systemic symptoms (cough, chest pain, fever, vomiting, anorexia and weight loss). She had no known allergies and consumed neither alcohol nor tobacco. There was no history of cancer in her family.

The physical examination revealed a normal Body Mass Index (BMI) of 24.1. The arterial blood pressure was normal (120/70 mmHg), she had mild tachycardia (105 beats per minute), normal respiratory rates (20 cycles of respirations per minute), and a low-grade fever (37.3ºC). The skin was pale and dry. The breast examination was normal. The pelvic exam showed normal external genitalia with a macroscopically normal ectocervix. The bleeding was similar to menstruation. The digital vaginal and rectal examination noted a highly painful enlarged uterus (approximately 14/12/12 cm) with irregular contours and reduced mobility.

Routine blood work-up was normal, showing normal function of the liver and kidney, normal hemostasis, and negative infection tests. Still, moderate anemia of 94 grams per liter (g/L) was present. The chest radiography offered normal relations, and the electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia (interpreted as secondary to anemia).

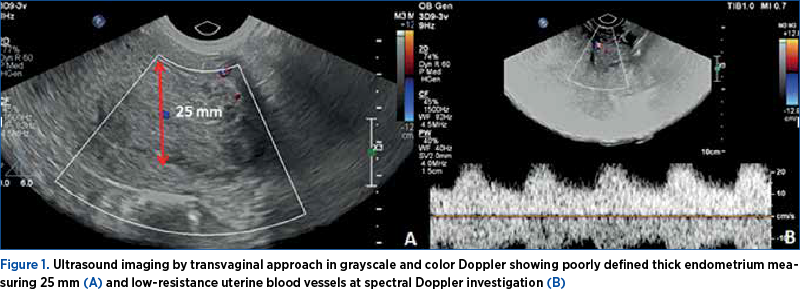

Ultrasound (US) exam of the pelvis revealed a uterus moderately increased in dimensions and a thick endometrium (roughly 25 mm), with an incompletely defined endometrial-myometrial junction. The in-patch interruption of the junction raised a high suspicion of endometrial carcinoma, with the invasion of the myometrium. Using US, we were able to confirm the irregular external contour, and we failed to demonstrate the internal shape of the uterus (Figure 1). We were also not able to demonstrate ovaries. The patient underwent a uterine curettage for hemostatic and biopsy purposes under general intravenous anesthesia, and fragments of the endometrium were sent for pathological analysis. After the procedure, she received analgesic medication and iron supplements.

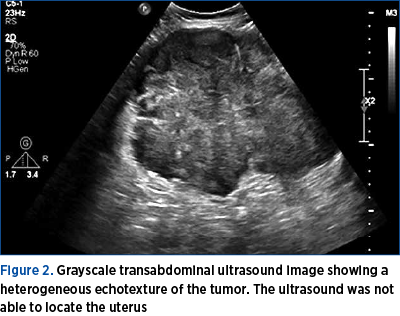

Two weeks later, the pathology reported a moderately differentiated endometrioid carcinoma. The next day, the patient was readmitted for a complete pre-surgery assessment. On the subsequent US scan, we were not able to demonstrate a clear image of the uterus anymore. An extremely large pelvic tumor was seen, that seemed to originate from the uterus (Figure 2). The tumor was described as “a solid heterogeneous mass with irregular contours”.

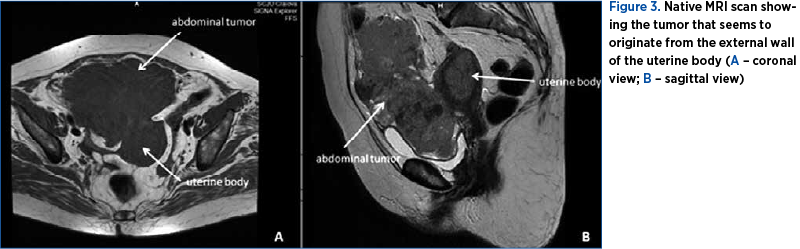

A native magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exam was performed, as the patient developed symptoms of iodine allergy. The MRI findings indicated a huge pelvic and abdominal tumor of 67/140/130 cm in diameter, with irregular contours and bladder external compression (Figure 3). The serologic tumoral markers (CA 12-5, CA 19-9, and CEA) came back in a normal range, along with a ROMA score of 20.74% which suggested a low risk of epithelial ovarian cancer.

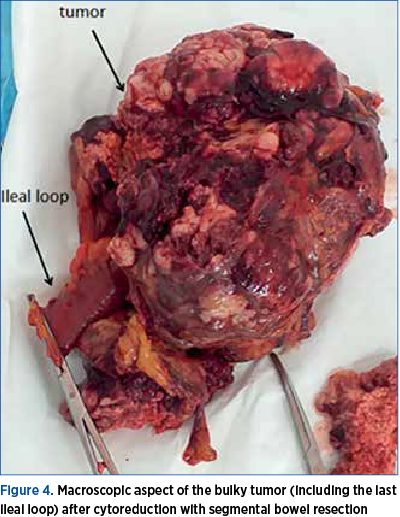

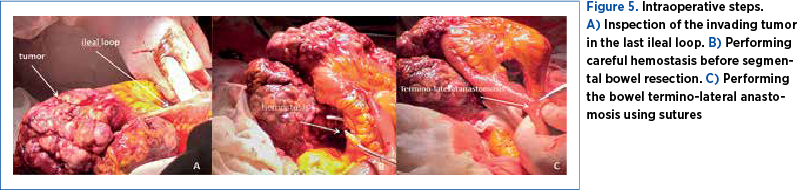

After counseling (the team including an oncologist), the patient consented to an exploratory laparotomy with cytoreduction if complete resection was not feasible. The surgery was approached by a multidisciplinary team (gynecologist and general surgeon). On opening, a small amount of abdominal fluid was aspired (40 ml). The surgical team inspected the 30-cm tumor that seemed intimately adherent to the uterus and also invading the last ileal loop (Figure 4). We performed a massive excision of the tumor along with segmental bowel resection and termino-lateral anastomosis (Figure 5), infracolic omentectomy, and we continued with a total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexal removal. Following the debulking surgery, lymphadenectomy was performed on the right side only, due to the risks of prolonged surgery on an unstable patient from the anesthetic point of view. The complex intervention allowed the staging of the disease as stage IV – advanced disease.

The patient had a favorable postoperative immediate evolution. She received antibiotics, anticoagulant drugs for prophylaxis of thrombotic events, and analgetic and anti-inflammatory drugs. She received 4 units of blood. She was discharged on the 10th day.

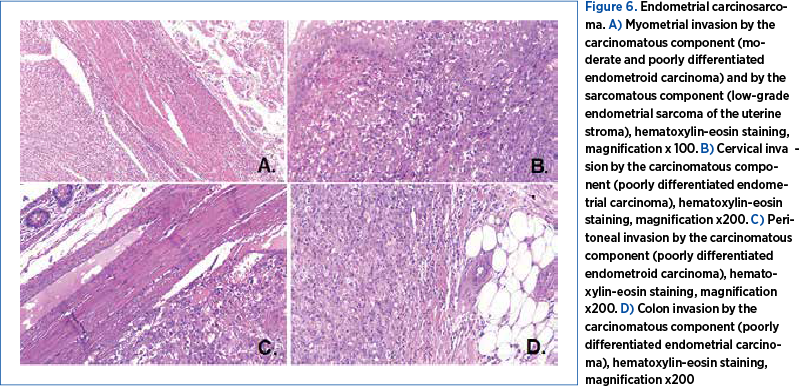

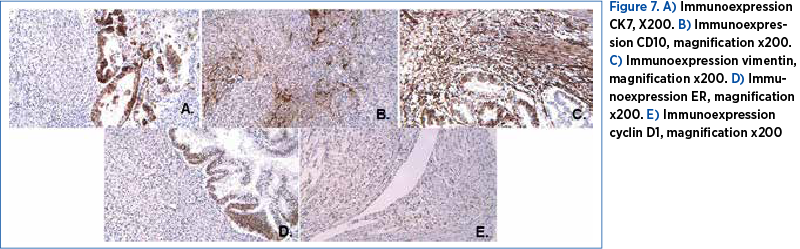

The cytology exam of the small volume of free fluid on the peritoneum was not conclusive, and the bacteriology exam was negative. The final histopathological study – that included the uterus, a mesocolon and an ileal segment, omentum and a peritoneum fragment – allowed the diagnosis of uterine carcinosarcoma. The carcinomatous component was composed of areas of moderate and poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma, while the sarcomatous component presented areas of low- and high-grade endometrial sarcoma of the uterine stroma (Figure 6). The sarcomatous elements of the uterine tumor were reported as >50%. The tumor invaded the cervix, the mesocolon and the peritoneum, exclusively through the carcinomatous component, represented by the poorly differentiated endometrioid carcinoma. The immunohistology analysis performed on fragments of the uterus, the mesocolon and the peritoneum confirmed the diagnosis of endometrial carcinosarcoma. The tumor proved positive for CK7, CD10, Vim, Cyclin D1 and ER, and negative for CD117, CD34, S100, CD45 and alpha actin (Figure 7). Surprisingly enough, the internal and external iliac group of lymph nodes unilaterally retrieved did not show malignancy. Obturator lymph nodes were also negative for malignancy. The omentum was found positive.

Postoperatively, the patient developed severe intractable anorexia, having no other signs, symptoms or complaints. Unfortunately, she was lost one month later. In the reported case, we didn’t succeed in applying multiple chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The patient had no scheduled follow-up appointments.

Discussion

Uterine carcinosarcoma, a type of endometrial carcinoma with a particular pathogenesis, often mimics an extrauterine condition, that is identified during extensive surgical staging. Uterine carcinosarcoma is extremely rapidly growing, as shown in our case.

Globally, the relative incidence of UCS is less than 5% of all uterine neoplasms(1) and 1% of all female genital tract malignancies(4). Uterine carcinosarcoma is frequently diagnosed in postmenopausal women, with a peak in incidence within the range of 62-67 years old(5). The risk of UCS is increased by obesity, nulliparity(6), Afro-American race(7), exposure to tamoxifen(8), and pelvic radiation(9). Oral contraceptive (OC) pill use seems to offer a protective effect against uterine carcinosarcoma. In our case, the patient was a menopausal non-obese Caucasian woman with no reported exposure to tamoxifen or pelvic radiation.

Initially, uterine carcinosarcoma was treated similarly to a high-grade sarcoma, but it responded unfavorably. Recent data point out that the aggressiveness of this malignancy is determined by the epithelial component(10). Most often, the immunohistochemical analysis of protein markers plays an important role as a differential diagnostic tool, as it did in this reported case.

Our patient presented the typical triad of symptoms of abnormal uterine bleeding, pain and rapid uterus growth(11), and no additional complaints. The first-choice method of imaging is the ultrasound examination, but computed tomography (CT) and MRI can be useful to detect extrauterine involvement of the tumor and to better plan the surgical intervention. Generally, the uterine biopsy identifies malignancy, but it is not able to confirm UCS(1). Similarly, in our case, the uterine curettage confirmed the uterine cancer, without any information about the sarcomatous elements.

The first-line therapy in women diagnosed with uterine carcinosarcoma without distant metastasis is total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral adnexal removal and retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy as a survival advantage, especially in patients with early-stage disease(12). Preoperatively and during surgery, our patient was staged as an advanced malignancy, despite the inability to perform and interpret a proper bilateral lymphadenectomy.

Most patients with UCS are good candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy (RT). All evidence pleads to the treatment of early stages of UCS after surgical resection with combination chemotherapy followed by vaginal brachytherapy or pelvic RT to ensure local control and prevent recurrence. Advanced stages should benefit after cytoreduction from a combination of chemotherapy and palliative RT(13). Endocrine therapy can be considered a helpful option as 30% of tumors express estrogen and/or progesterone receptors, but it has not yet been validated by clinical trials(13). Unfortunately, our patient was lost one month postoperatively, without the possibility of any adjuvant therapy.

A close follow-up, including a clinical examination with vaginal cytology and a full body CT, is advisable for all cases of UCS.

Uterine carcinosarcoma is an aggressive tumor, with a recurrence rate higher than 50%(1). Predictors of a poor prognosis include stage, the grade of the sarcomatous component, the depth of the myometrial invasion, the lymphovascular space involvement, and peritoneal cytology(14). Our patient presented no elements for an improved survival rate: age below 40 years old, the utilization of postoperative radiotherapy, undergoing lymphadenectomy, and early diagnosed stage of the disease(14). Unfortunately, another worth mentioning aspect in the presented case is the lack of serial routine gynecologic exams.

As the epithelial element seems responsible for most metastasis and vascular invasion, UCS has been reclassified as a metaplastic form of endometrial carcinoma. Behaving aggressively, uterine carcinosarcoma is still included in uterine sarcomas studies, as well as in “mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors” of the 2014 WHO classification(15).

Uterine carcinosarcoma tends to occur in postmenopausal women, as did in our case. Most of them present with abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain and uterine enlargement. At presentation, extrauterine spread (FIGO stages III-IV) is found in up to one-third of cases. Although still considered a rare tumor, the reported incidence seems to be gradually increasing(16,17). The sarcomatous elements of the uterine tumor (present in more than 50% in our case) are associated with a decreased survival(17). The contemporary view ads next-generation sequencing and molecular techniques as new and hopefully important tools in managing UCS.

Due to its rarity, there are no guidelines for specific treatment in uterine carcinosarcoma. Surgical resection remains the best curative option for localized disease. Radiotherapy, traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, and chemoradiation improve further the outcome. There is no consensus regarding the best regimen in palliative chemotherapy. The identification of the histopathological and molecular features has the potential to help in finding new therapeutic agents, potentially more effective(18). Uterine carcinosarcoma remains an aggressive type of cancer, with poor survival rates(19,20).

Conclusions

The triad of symptoms abnormal uterine bleeding, pain and rapid uterus growth occurring in menopausal women should alert physicians to include uterine carcinosarcoma in the differential diagnosis of gynecologic pathology. This manuscript intends to raise awareness about this condition in daily practice. Increased vigilance and serial gynecological exams may help in reaching an early diagnosis. A prompt, complex and multidisciplinary therapeutic strategy is needed.

Informed consent. Written informed consent was obtained from the family of the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in the study followed the ethical standards of the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova and the County Emergency Clinical Hospital of Craiova, Romania.

Acknowledgment. We thank our colleagues and physicians in the Histopathology Department of the County Emergency Clinical Hospital of Craiova for their involvement.

Corresponding author: Ştefania Tudorache, e-mail: stefania.tudorache@gmail.com

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Cantrell LA, Blank SV, Duska LR. Uterine carcinosarcoma: A review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(3):581-588.

-

Cherniack AD, Shen H, Walter V, et al. Integrated Molecular Characterization of Uterine Carcinosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(3):411-423.

-

Silverberg SG, Major FJ, Blessing JA, et al. Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed mesodermal tumor) of the uterus. A Gynecologic Oncology Group pathologic study of 203 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1990;9(1):1‑19.

-

Zagouri F, Dimopoulos AM, Fotiou S, Kouloulias V, Papadimitriou CA. Treatment of early uterine sarcomas: disentangling adjuvant modalities. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:38.

-

Gadduci A, Cosio S, Romanini A, Genazzani AR. The management of patients with uterine sarcoma: A debated critical challenge. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65(2):129‑42.

-

Harano K, Hirakawa A, Yunokawa M, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with uterine carcinosarcoma: a multi-institutional retrospective study from the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21(1):168-176.

-

Singh R. Review literature on uterine carcinosarcoma. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10(3):461-8.

-

Hubalek M, Ramoni A, Muller‑Holzner E, Marth C. Malignant mixed mesodermal tumour after tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95(1):264‑6.

-

Meredith RF, Eisert DR, Kaka Z, Hodgson SE, et al. An excess of uterine sarcomas after pelvic irradiation. Cancer. 1986;58(9):2003‑7.

-

Artioli G, Wabersich J, Gardiman MP, Borgato L, Garbin F. Rare uterine cancer: carcinosarcomas. Review from histology to treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94(1):98-104.

-

Ravishankar P, Smith DA, Avril S, Kikano E, Ramaiya NH. Uterine carcinosarcoma: a primer for radiologists. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44(8):2874-2885.

-

Koh WJ, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, et al. Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(2):170-199.

-

Homesely HD, Filiaci V, Markman M, et al. Phase III trial of ifosfamide with or without paclitaxel in advanced uterine carcinosarcomas. Gynaecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):526‑31.

-

Ramondetta L, Bodurka D, Deavers M, Jhingran A. Uterine Sarcomas. In: M. D. Anderson Cancer Care Series, Gynecologic Cancer. Edited by: Eifel PJ, Gershenson DM, Kavanagh JJ, Silva EG. Springer. New York; 2006:125-147.

-

Mbatani N, Olawaiye AB, Prat J. Uterine sarcomas. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2018;143:51–8.

-

Liao CI, Caesar MA, Lee D, Chan A, Darcy KM, Tian C, Kapp DS, Chan JK. Increasing incidence of uterine carcinosarcoma: A United States Cancer Statistics study. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2022;40:100936.

-

Matsuzaki S, Klar M, Matsuzaki S, Roman LD, Sood AK, Matsuo K. Uterine carcinosarcoma: Contemporary clinical summary, molecular updates, and future research opportunity. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;160(2):586-601.

-

Pezzicoli G, Moscaritolo F, Silvestris E, Silvestris F, Cormio G, Porta C, D’Oronzo S. Uterine carcinosarcoma: An overview. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;163:103369.

-

Terblanche L, Botha MH. Uterine carcinosarcoma: A 10-year single institution experience. PLoS One. 2022;17(7):e0271526.

-

Toboni MD, Crane EK, Brown J, Shushkevich A, Chiang S, Slomovitz BM, Levine DA, Dowdy SC, Klopp A, Powell MA, Thaker PH. Uterine carcinosarcomas: From pathology to practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162(1):235-241.