Autocompasiunea la personalul din îngrijirile paliative – impactul unei instruiri specifice

Self-compassion for palliative care personnel – the effect of specific training

Abstract

Self-compassion is a construct with real implication in case of palliative care. Self-compassion represents a personal resource and support for self-care. The personnel who provide care in the palliative settings can benefit from protective factors and self-compassion, but at the same time they feel the pressure of a major mental and physical burden. The aim of this study was to assess self-compassion in relation with palliative care personnel, care workers from hospice, oncology area and relatives of palliative care patients. The design of the study includes an evaluation of the self-compassion before and after a 90-minute training session done on a group of people from palliative care. The level of self-compassion was assessed with the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), with 26 items, proposed by Kristin Neff. The present study indicates that personnel in palliative care can benefit from special training in order to increase the level of self-compassion and at the same time to reduce the negative dimension of self-judgement, isolation and overidentification which interferes with the positive state of mind and health.Keywords

palliative careself-compassionpalliative settingsisolationcommon humanityRezumat

Autocompasiunea este un construct cu implicaţii reale în cazul îngrijirilor paliative. Autocompasiunea reprezintă o resursă personală şi un sprijin pentru îngrijirea propriei persoane. Personalul care acordă asistenţă în domeniul îngrijirilor paliative poate beneficia de factori de protecţie şi de autocompasiune, dar în acelaşi timp simte presiunea unei încărcături psihice şi fizice majore. Scopul acestui studiu a fost de a evalua autocompasiunea în relaţia cu personalul din îngrijirile paliative, personalul de îngrijire din hospice, zona oncologică şi cu rudele pacienţilor cu îngrijiri paliative. Designul studiului include o evaluare a autocompasiunii înainte şi după o sesiune de antrenament de 90 de minute, efectuată la un grup de persoane din îngrijirile paliative. Nivelul de autocompasiune a fost evaluat cu ajutorul Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), cu 26 de itemi, propusă de Kristin Neff. Acest studiu indică faptul că personalul din domeniul îngrijirilor paliative poate beneficia de formare specială, pentru a creşte nivelul de autocompasiune şi, în acelaşi timp, a reduce dimensiunea negativă a autocriticii, izolării şi supraidentificării, care interferează cu starea mentală pozitivă şi cu sănătatea.Cuvinte Cheie

autocompasiuneîngrijire paliativăizolareumanitateIntroduction

Self-compassion represents a personal resource and support for self-care. In case of palliative care, self-compassion is important and ensures that needs are not neglected, particularly during times of suffering. Self-compassion in relation with palliative care was previously studied(1) and it appears to be an important resource in hospice and palliative care. The mentioned research indicates that self-compassion “supports self-care and alleviates suffering by improving the social, psychosocial and spiritual well-being of patients and healthcare professionals”.

Since the 2000s, American researcher Kristin Neff has explored, framed and quantified the concept of compassion in relation to her own person, theorizing, operationalizing and applying the concept of self-compassion(2). Self-compassion refers to the ability to show compassion, understanding and protection to oneself. The manifestation of self-compassion has implications on the functioning and efficiency of the person in interactions with society and relationships. The impact of applying self-compassion has been documented through numerous studies by the author of the concept. The relationships of self-compassion with trauma, self-esteem, health, physiological functioning, burnout, resilience, palliative care and oncology were studied before. In another recent research(3), based on four sessions of face‑to‑face self-compassion intervention for personnel of someone with a life-limiting or terminal illness, researchers found that the personnel discovered a kinder, less judgmental way of seeing themselves, experiencing a greater sense of calm or relaxation and the development of a more positive outlook with benefits for them. Based on these findings, self-compassion can be used to assess palliative care patients’ relatives.

The importance and evidence of applying self-compassion and self-care in both personal and professional settings was discussed by the studies of Mills et al.(4,5) The authors underline that self-care is a proactive, holistic and personalized approach used to enhance capacity for compassionate care of patients and their families.

In recent years, more evidence has supported the idea that self-compassion is a construct with emerging implication for the promotion of health and wellbeing.

The aim of the study

The aim of this study was to assess self-compassion in relation with palliative care personnel, care workers from hospice, oncology area and relatives of palliative care patients.

Materials and method

The design of this study includes an evaluation of the self-compassion before and after a 90-minute training session done on a group of people from palliative care.

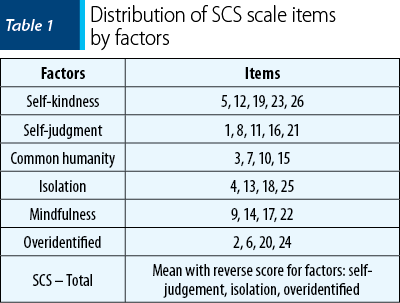

The level of self-compassion was assessed with the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), with 26 items, proposed by Kristin Neff. The scale is available in English on the author’s website(6), with permission to be used by the research community. The scale includes several dimensions of self-compassion, as presented in Table 1.

For the present study, the self-compassion assessment tool proposed by Kristen Neff was used. For the self-compassion scale (SCS), the author’s consent for the use of the scale for research purposes was requested and received in advance. The self-compassion scale was translated into Romanian by two professional translators, through the translation and back-translation procedure; no psychometric validation of the scale on the Romanian population is in use. The assessment tool was sent in an electronic format to different target groups: oncology, palliative care centers, support groups for families in palliative care, psychological offices, focus members of previous groups, members of the BIOGENONCO project etc.

The evaluation scale was completed by 62 people who received the subsequent invitation to participate in a training session that took place in an online format and who agreed to it.

The webinar entitles Self-compassion: personal and therapeutic resource ran on the 8th of May 2021 in an online format on zoom platform for a period of 90 minutes. The webinar was held by the two of the authors of the present study. The webinar was a short training. The participants were instructed about the aim of the study and a consent of participation was asked. The focus of the webinar was on the compassion and self-compassion concept, the emotions, emotion awareness and how to raise awareness, monitor emotions and mindfulness, reduce self-criticism, isolation and self-judgement. The annotate function of zoom was activated for an interactive session format.

After the webinar, the participants received a short guide with materials from the training and invitations to fill in again the online form for the self-compassion scale. The scale in an online format is available on the internet. Participants were evaluated before (https://cutt.ly/cTxZWFb) and after the training (https://cutt.ly/ITxZLyn) with the same instrument. Comparisons of safe-compassion levels were performed.

The subsequent procedure entailed the statistical processing and interpretation of data, in order to compare self-compassion in the pre-training phase and the post-training phase.

Participants

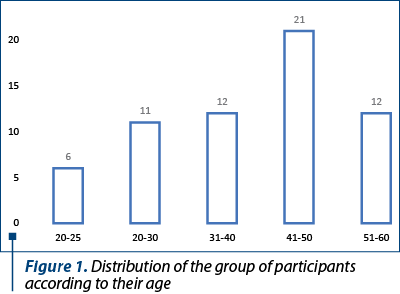

A number of 62 persons participated in the study, with different age range and with different interactions in the palliative care: hospital staff, staff from the oncological palliative area, members of family of patients with oncological diseases etc.

The distribution of participants according to age is represented in Figure 1. Most participants were in the 41-50 years old age range, but all age ranges were represented.

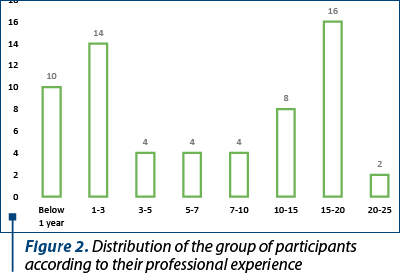

Regarding the professional experience, most of the participants have wide experience in the field; however, a relatively large number are also participants with a professional experience below five years. The distribution of professional experience is presented in Figure 2.

Results

The results obtained from the statistical analysis indicate differences related to age and experience, but also differences between initial and post-training evaluation in terms of self-compassion. There is no difference in SCS results based on the category of personnel.

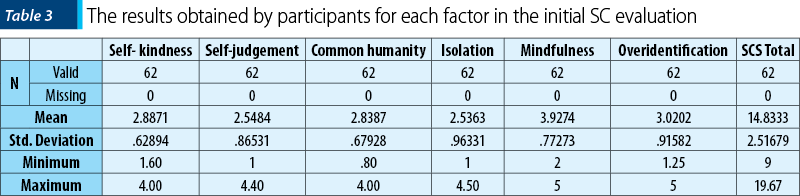

The results obtained in the pre-training session indicate different values for the factors with positive impact (self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness) and for factors with a negative value, such as isolation, overidentification or self-judgment.

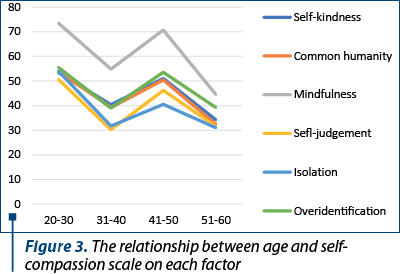

The relation between age and self-compassion is displayed in Figure 3.

The mindfulness factor has the highest value, and the isolation factor has the lowest value.

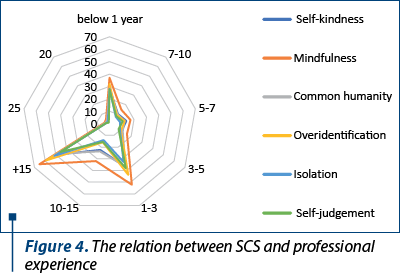

The relationship between the professional experience and self-compassion indicates that self-judgement and overidentification factors have high scores in relation with poor experience or increased professional experience. For the positive factor, the mindfulness factor is in direct relationship with professional experience.

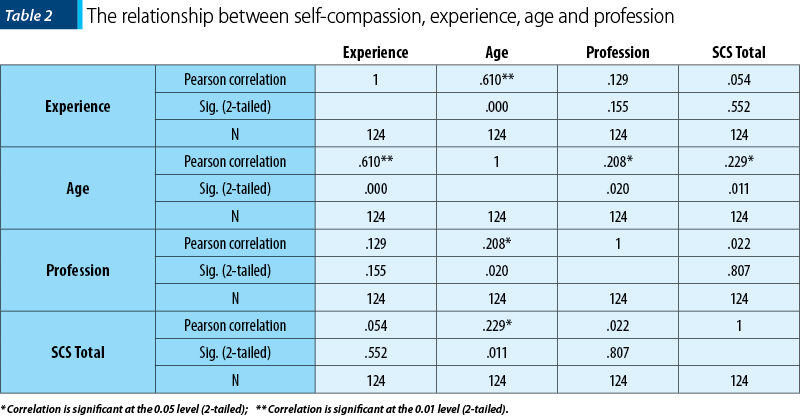

Age, experience and profession in relationship with the total score for self-compassion scale was of interest. We observe that self-compassion score is not influenced by age or professional experience; however, age is in direct relationship with the experience reported by the participants.

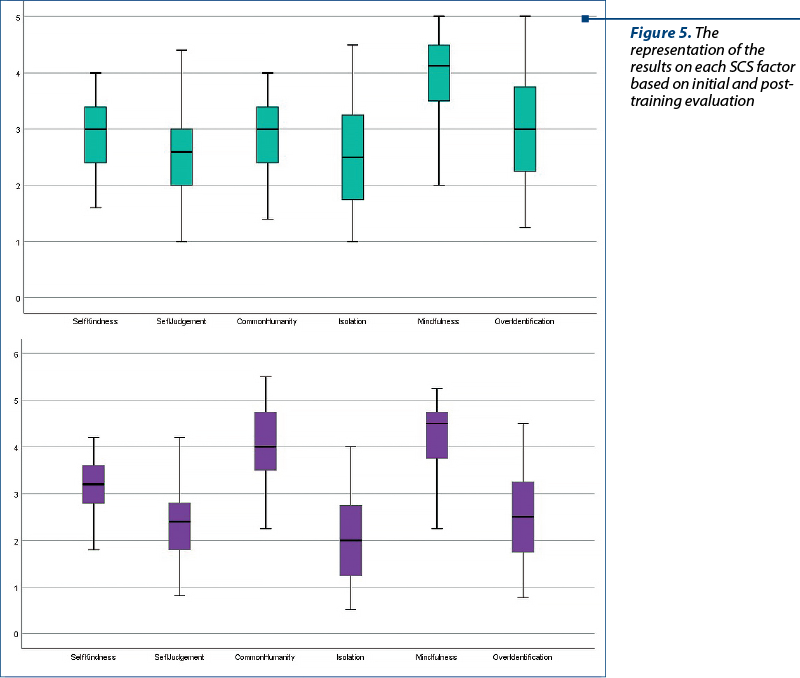

The representation of the values obtained for each dimension in the SCS indicates that the results in the final evaluation are different from the initial evaluation. In the post-intervention evaluation, the reporting is done at the threshold of 6 points, for mindfulness the value targets the number 5, and the isolation factor had much lower values. This entails that items with a negative valence on the SCS scale have a lower significance.

The descriptive statistics indicates that self-kindness (M=2.88; SD±0.628) and mindfulness (M=3.92; SD±0.772) are the factors with positive values and higher scores, while overidentification (M=3.02; SD±0.91), with a minimum of 1.25 and a maximum of 5, is the highest score for factors with negative impact on self-compassion.

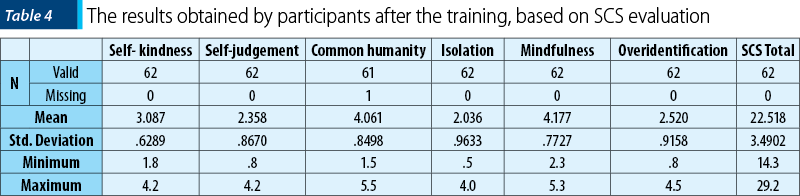

The results after the training indicate changes in relation to the total score of the self-compassion scale (SCS), but also for each item separately. For common humanity, on the initial evaluation, the score was M=2.83 (SD±.679) and on post-training evaluation the score was M=4.06 (SD±0.84). For overidentification, the value decreased from M=3 (SD±.91) to M=2.52 (SD±0.91). This represents a positive aspect as the overidentification has a negative impact on self-compassion. The results of each factor are presented in Table 4.

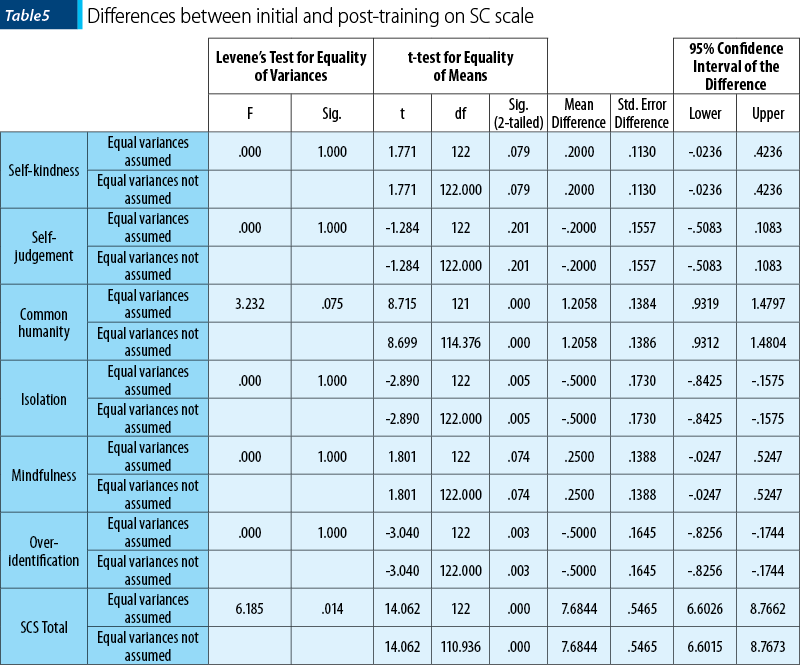

The evaluation of the post-training level of self-compassion indicates differences between initial and post-training evaluation. The results were statistically significant for common humanity (CH), isolation (I), overidentification (OI) and for the total score of SCS. The results from the pre-test (M=2.83, SD=679) and post-test (M=4.06, SD=84) CH values indicate that the participation in a 90-minute training session resulted in an improvement in self-compassion (t(62)=8.71, p=0.000). The results from the pre-test (M=2.53, SD=0.96) and post-test (M=2.02, SD=0.96) isolation value indicate that the participation in a 90-minute training session resulted in a decrease in isolation (t(62)=-2.89; p=0.005), with a good impact on self-compassion. Also, the results from the pre-test (M=3.02, SD=0.91) and post-test (M=2.52, SD=0.91) OI value indicate that the participation in a 90-minute training session resulted in a decreased in overidentification (t(62)=-3.04; p=0.003), with good impact for self-compassion. Overall, the results from the pre-test (M=14.83, SD=2.51) and post-test (M=22.51, SD=3.49) Self Compassion Scale total score indicate that the participation in a 90-minute training session resulted in an improvement in self-compassion (t(62)=14.06, p=0.000). The full results are presented in Table 5.

Discussion

The results obtained on the scale of self-compassion indicate a positioning of palliative care personnel in the category of staff at high risk of being subjected to mental pressure. The results are in concordance with those from previous research on self-compassion(2). Dimensions with negative valence, self-judgment, isolation and overidentification are at low thresholds, and those with positive valence, such as common humanity, self-compassion and self-kindness, are at a higher level on the charts. This can have an impact on functioning, both as an individual and support personnel in palliative settings. In professions that by their nature involve human interaction, empathy and dedication, a risk factor is represented by exhaustion, decreased mental resources and the onset of burnout. If the personnel neglect their own needs, emotional fatigue does not take long to manifest, and personal exhaustion appears as a natural consequence.

Risk factors include helplessness and a sense of inefficiency; protective factors include practicing personal care and recovery techniques and spending time with friends and family(7). In a previous study(8), the researchers found that rehabilitation professionals have a high risk of exhaustion. Specifically, the risk factors were represented by emotional exhaustion (32%), depersonalization (13%) and lack of personal satisfaction (9%). Similar to the results of the present study, in an Italian study(8), there were no differences regarding the risk factors between different settings.

The personnel from palliative care benefits from the 90-minute training with specific instruction. These trainings reduce the negative impact of self-judgment and overidentification and increase the positive aspect of common humanity and mindfulness. This result is in concordance with the one observed in the study of Diggory et al.(3) who noticed that, through specific training, carers discovered a kinder way of seeing themselves, be less judgmental and allowing themselves be aware that they had their own individual needs. Similar observation were underlined by Galiana et al.(9) who consider that, “for palliative care professionals, the cultivation of self-compassion is equally needed as compassion for others”. Similarly, Survey et al.(10) consider that “cultivating a compassion self-to-self relationship might have an important effect attenuating the link between pain and depression in palliative care”.

Self-compassion has higher scores in relation to age and professional experience, and lower scores at the beginning of careers or care interaction. One explanation may be that, as palliative care personnel gain experience, they understand that the need for self-protection is real, and that isolation and self-criticism work against oneself. They understand that, in order to be effective, they must be equally compassionate with those they care for, but also with themselves. These results are in agreement with those observed in other professional categories in the previous studies done by the authors(11).

The results of this study are in relation to those identified by other studies(5,8) which assert that beyond empathy is compassion and that it helps foster a more effective and unprejudiced approach. Self-compassion also involves the use of mindfulness techniques, proven useful in palliative care(12). In the present study, palliative care personnel scored high on mindfulness, and this may be a factor in personal protection.

Conclusions

Self-compassion is a construct with real implications in palliative care. The personnel who provide care in the palliative setting can benefit from protective factors and self-compassion, but at the same time they feel the pressure of a major mental and physical burden. The personnel working in this sector does display an increase level of mindfulness, kindness and humanity, but they also display high levels of isolation and overidentification, with negative impact on the long term.

The present study indicates that personnel in palliative care can benefit from special training to increase the level of self-compassion and, at the same time, reduce the negative dimension of self-judgement, isolation and overidentification that interfere with the positive state of mind and health.

Disclaimer: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in conducting and publishing this study.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by the grant Partnership for the transfer of knowledge in biogenomics applications in oncology and related fields – BIOGENONCO, project co-financed by FEDR through Competitiveness Operational Programme 2014-2020, contract no. 10/01.09.2016.

Bibliografie

-

Mesquita Garcia AC, Domingues Silva B, Oliveira da Silva LC, Mills J. Self-compassion In Hospice and Palliative Care: A Systematic Integrative Review.

-

J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2021;23(2):145-154. doi:10.1097/NJH.0000000000000727

-

Neff K. Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):85–101.

-

Diggory K, Reeves A. ‘Permission to be kind to myself’. The experiences of informal carers of those with a life-limiting or terminal illness of a brief self-compassion-based self-care intervention. https://doi.org/101080/0969926020211972722 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 15]; Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09699260.2021.1972722

-

Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Palliative care professionals’ care and compassion for self and others: a narrative review. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2017 May 1;23(5):219–29.

-

Mills J, Chapman M. Compassion and self-compassion in medicine: self-care for the caregiver. Australas Med J. 2016;9(5):87–91.

-

Neff K. Self-Compassion [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 21]. Available from: https://self-compassion.org/

-

Zur. Therapist Burnout: Facts, Causes and Prevention [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 22]. Available from: https://www.zurinstitute.com/clinical-updates/burnout-therapists/

-

Bruschini M, Carli A, Burla F. Burnout and work-related stress in Italian rehabilitation professionals: A comparison of physiotherapists, speech therapists and occupational therapists. Work. 2018;59(1):121–9.

-

Galiana L, Sansó N, Muñoz-Martínez I, Vidal-Blanco G, Oliver A, Larkin PJ. Palliative Care Professionals’ Inner Life: Exploring the Mediating Role of Self-Compassion in the Prediction of Compassion Satisfaction, Compassion Fatigue, Burnout and Wellbeing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(1):112-123. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.07.004

-

Survey H, Guerra J, Santiago L, Carreiras D. The role of self-compassion in the relationship between pain and depression in palliative patients. European Psychiatry. 2021;64(S1):S430-S431. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.1148.

-

Trifu R, Miclea B, Herţa D, Puşcaşu S, Bodea-Haţegan C, Coman H. Auto-compasiunea şi auto-eficacitateaca – resurse personale în cazul terapeuţilor. Rev Română Ter Tulburărilor Limbaj şi Comun [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1;7(1):3–16.

-

Brooker J, Julian J, Millar J, Prince HM, Kenealy M, Herbert K, et al. A feasibility and acceptability study of an adaptation of the Mindful Self-Compassion program for adult cancer patients. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18(2):130–40.