Relaţia dintre acceptarea necondiţionată a propriei persoane şi fuziunea cognitivă în psihoză

The relationship between unconditional self-acceptance and cognitive fusion in psychosis

Abstract

Introduction. Psychosis is one of the most debilitating psychiatric disorders, being characterized by loss of contact with reality, without consciousness being affected. Cognitive fusion as a concept is governed by metacognitive processes, in which thought dominates and directs behavior, perceived by the psychotic patient as valid and in line with reality.Materials and method. The sample consists of two groups, a target group (N=20), which includes patients diagnosed with psychosis, hospitalized in the Second Psychiatry Clinic from Târgu-Mureş, and a control group (N=20), consisting of students from the “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science and Technology from Târgu-Mureş. There were applied the self-acceptance questionnaire (USAQ) to assess self-esteem and the cognitive fusion questionnaire (CFQ).

Aim. The aim of this study is to highlight the relationship between the unconditional acceptance of one’s own person of the subjects diagnosed with psychosis and the cognitive fusion.

Results. The statistical interpretation of the data showed a statistically significant difference between the target group and the control group in terms of cognitive fusion (M=26.15; t=13.07, df=38, p<0.0001; CI -62.42,-45.68), but without differences between the two groups in terms of unconditional acceptance of one’s own person (M=34.95; t=1.97, df=38, p>0.05; CI -0.27, 19.28).

Conclusions. Cognitive fusion is a mechanism that is found more in psychotic patients than in controls. The present work highlights the need for more studies regarding the field of cognitive fusion and unconditional self-acceptance, for a better understanding of the factors that trigger or maintain psychotic symptoms.

Keywords

psychosisacceptancecognitive fusionRezumat

Introducere. Psihoza este una dintre cele mai debilitante afecţiuni psihiatrice, fiind caracterizată de pierderea contactului cu realitatea, fără ca starea de conştienţă să fie afectată. Fuziunea cognitivă drept concept este guvernată de procesele metacognitive, în care gândul domină şi dirijează comportamentul, percepute de pacientul psihotic ca fiind valide şi conforme cu realitatea.Materiale şi metodă. Eşantionul este format din două grupuri: un grup-ţintă, care cuprinde pacienţi diagnosticaţi cu psihoză, spitalizaţi în Clinica Psihiatrie II din Târgu-Mureş, şi un grup de control, format din studenţi la Universitatea de Medicină, Farmacie, Ştiinţe şi Tehnologie „George Emil Palade” din Târgu-Mureş. Au fost aplicate chestionarul de acceptare necondiţionată a propriei persoane (USAQ) pentru evaluarea stimei de sine şi chestionarul pentru fuziune cognitivă (CFQ), în vederea evaluării dimensiunii fuziune cognitivă.

Scop. Obiectivul acestui studiu este evidenţierea relaţiei dintre acceptarea necondiţionată a propriei persoane a subiecţilor diagnosticaţi cu psihoză şi fuziunea cognitivă.

Rezultate. Interpretarea statistică a datelor evidenţiază o diferenţă semnificativă între grupul-ţintă şi grupul de control în ceea ce priveşte dimensiunea fuziunii cognitive (M=26,15; t=13,07, df=38, p<0,0001; CI -62,42 – -45,68), dar cu scoruri similare privind acceptarea de sine necondiţionată pentru pacienţii cu psihoză şi persoanele din grupul de control (M=34,95; t=1,97, df=38, p>0,05; CI -0,27 – 19,28).

Concluzii. Fuziunea cognitivă este un mecanism cognitiv întâlnit într-o măsură mai mare la pacienţii cu psihoză comparativ cu grupul de control. Acest studiu subliniază necesitatea unor studii suplimentare privind domeniul fuziunii cognitive şi al acceptării necondiţionate a propriei persoane, pentru o înţelegere mai bună a factorilor care declanşează sau menţin simptomele psihotice.

Cuvinte Cheie

psihozăacceptarefuziune cognitivăIntroduction

The term psychosis was used for the first time by Canstatt in 1841 and then published in a study in 1845 by Ernst von Feuchtersleben. Over time, the term psychosis has had different meanings. At the end of the 19th century it was subdivided by Wenicke into somatopsychosis, which explained the fact that one’s own body’s consciousness is affected, autopsychosis, meaning the impairment of one’s own personality consciousness, and allopsychosis, with the impairment of consciousness and outside world; this was the first time that the term psychosis was used as a whole. At the beginning of the 20th century, Kraepelin divided psychosis into dementia praecox (future schizophrenia), categorizing it as an organic psychosis because the consequence was dementia, and manic-depressive disorder as functional psychosis. Later he classified them as endogenous disorders. Jaspers outlined the difference between neurosis and psychosis based on the insight. Schneider would introduce the concept of psychotic symptomatology(1).

Psychosis is one of the most debilitating psychiatric disorders, being characterized by loss of contact with reality without consciousness being affected, with the presence of hallucinations and delusional ideation as the main symptoms, with disorganized behavior, impaired attention and both cognitive and emotional symptoms that may add to the psychopathological picture(2).

Psychosis includes schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, schizotypal disorder, bipolar disorder, unipolar disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, induced psychotic disorder, and psychosis in the elderly(2).

Unconditional self-acceptance represents the absence of one’s tendency to globally evaluate his/her self-worth, while maintaining a critical attitude towards particular behaviors which can be adaptive or maladaptive. This construct correlates with various mental health indicators, such as subjective well-being, positive or negative affectivity, anxiety and depression(3). Unconditional self-acceptance was also found to be a moderator in the relationship between irrational beliefs and psychological distress(4,5).

The difficulties encountered when we face emotional suffering as a thought-related process do not refer to the fact that we have the wrong thoughts, but rather to the increased attention we pay to the time spent with a certain thought. Too little time is spent observing a thought. The problem with cognitive fusion is the response to thoughts and emotions. The automatic perception that a thought dictates our behavior underlies cognitive fusion(6).

Due to the shortcomings of traditional methods such as pharmacology, although their effectiveness is proven, through specific methods to increase acceptance of hallucinations or delirium, the belief in symptomatology is reduced. This change contributes to a lower rate of relapses and hospitalization periods, and finally to the decrease of distress perceived by the patient in relation to psychotic symptoms(7).

From the point of view of acceptance, a psychotic patient who feels a close connection with dysfunctional cognitions has certain similarities with a patient addicted to substances. Resistance to change or to alter the experience of cognitive symptoms is a mechanism of avoidance meant to avoid possible negative experiences, because the involvement in reality increases and, as a direct result, the patient feels an anxiety in relation to the psychotic symptomatology and a dissonance at the level of perception. By acceptance we obtain a reduction of the perceived distress because the suppression of thoughts that involve an intentionality in the elimination or control of thoughts can paradoxically increase their intensity or an intensification of reactions. This chronic tendency is an important component of emotional avoidance(8).

Accepting and observing experiences in psychotic symptoms without an intention to change it generate a strong mechanism by which the patient can stop this sustained effort to change thoughts and emotions. Attention can be focused on the reactions and the relationship with the symptoms. By accepting and diminishing the feeling of control, the level of susceptibility is increased. Studies on psychotic patients show us that the interpretation of hallucinations – and not their content – determines the level of distress associated with them(9).

Acceptance from the proposed perspective does not imply a passive process towards the caused suffering or an incomplete level of improvement; on the contrary, it refers to the adoption of an active position and an intention to experience or to have thoughts, feelings or physical sensations outside the comfort zone. The treatment includes both a pharmacological approach focused on reducing positive and negative symptoms, and focusing on the subjective quality of life and well-being(10,11).

Objective

The aim of this study is to highlight the relationship between unconditional self-acceptance of subjects diagnosed with psychosis and cognitive fusion.

Method

Participants and procedure

This is an observational-transversal study. The research included a number of 40 subjects divided into two groups. The target group included patients diagnosed with psychosis, hospitalized in the Second Psychiatry Clinic from Târgu-Mureş, with an average age (Mage) of 36.80 years old. The control group consisted of students from the “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science and Technology of Târgu-Mureş, with an average age of 24.20 years old. The subjects were applied The Self-Acceptance Questionnaire (USAQ) in order to assess self-esteem and The Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ) in order to assess cognitive fusion.

Instruments

The Self-Acceptance Questionnaire contains 20 items that measure the unconditional self-acceptance. It was designed by Chamberlain and Hagga in 2001 and consists of 9 items that indicate high levels of unconditional self-acceptance and 11 items that reflect low unconditional self-acceptance. The internal consistency coefficient Cronbach’s alpha is 0.72 in the Romanian population, expressing the fact that the items of the questionnaire evaluate the same construct – the unconditional acceptance of the person(12).

The Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire consists of 7 items, rated from 7 points (always true) to 1 point (never true), that measure the level at which a person tends to relive certain negative emotions and events. The score is calculated by summing the statements, a higher score representing a higher fusion(13).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05, with a 95% confidence interval. The Student T test was used to compare unpaired parametric data.

Results

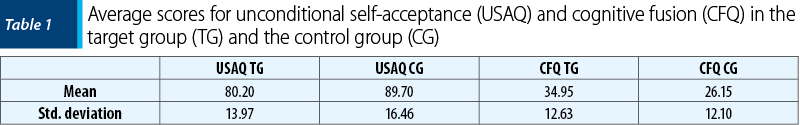

As shown in Table 1, the average unconditional self-acceptance scores were M=80.20 (SD=13.97) for the target group, and M=89.70 (SD=16.46) for the control group, respectively. This suggests similar unconditional self-acceptance levels for psychotic patients (M=80.20) and controls (M=89.70), with only a slightly lower mean for people with a psychiatric diagnosis. On the other hand, the average cognitive fusion values were M=34.95 (SD=12.63) for the target group, and M=26.15 (SD=12.10) for the control group, respectively. Therefore, this indicates a higher level of cognition fusion in psychotic patients when compared to healthy controls.

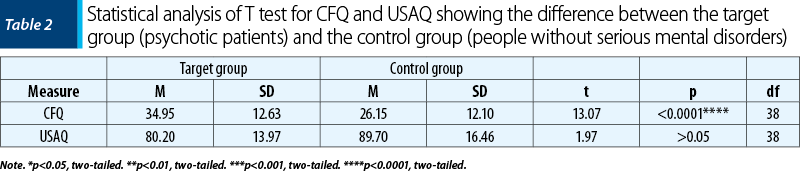

Our results demonstrate a statistically significant difference between the target group (M=34.95) and the control group (M=26.15) regarding the cognitive fusion dimension. The 95% CI ranges from -62.42 to -45.68, with a mean difference of -54.05 ± 4.13. The difference between the two groups is statistically significant, where t=13.07, df=38, and p<0.0001. However, we found no significant statistical differences between the two groups regarding the unconditional self-acceptance dimension. The 95% CI ranges from -0.27 to 19.28, with a mean difference of 9.50±4.83. The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant, where t=1.97, df=38, and p>0.05. Our results are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

The present study is the first investigation of unconditional self-acceptance in psychosis patients, as compared to healthy controls. However, our results did not show that people with psychosis have significantly lower unconditional self-acceptance scores than the general population. This is not in line with other research showing that negative schema and beliefs about the self may be involved in the onset or maintenance of psychosis(14,15), as well as those which emphasize the high occurrence of internalized stereotypes in the form of shame or negative self-appraisals in both patients with recurrent psychosis and people at ultra-high risk(16).

Similarly, our findings did not support the existing evidence on the association between irrational beliefs and paranoid thoughts, which is the most common type of delusion in psychosis(17). Despite this, several alternative explanations may account for our results. First, lacking emotional awareness and clarity is common among psychotic patients, which may sometimes lead to a disorganized sense of self(18,19). Given that unconditional self-acceptance implies an evaluation of the self as a unitary construct and people with psychosis may present an altered self-experience, the notion of self-acceptance may not be so iconic for this category of patients. Moreover, the therapeutic interventions focusing on cognitive and insight deficits are a promising direction for recovery in psychosis(20). Secondly, some studies indicated positive changes in terms of self-understanding and acceptance following a first psychotic episode. That is, after experiencing a psychotic episode, some people assigned a constructive meaning to such an event, integrating it with other aspects of the self and even finding new life pursuits(21). Likewise, personal interpretations of psychotic experiences in non-clinical groups were shown to be protective for a positive self-image and self-acceptance(22). From this perspective, maintaining a high unconditional self-acceptance may act as an adaptive coping strategy with psychotic experiences in psychiatric patients, but further investigations are necessary to explore this hypothesis in more detail(23).

According to the results of the present study, cognitive fusion is positively associated with psychotic elements within the group of patients studied compared to the control group of subjects without psychiatric disorders. The relationship between the cognitive fusion of patients with psychosis becomes important when we discuss the patient’s motivation from the perspective of acceptance. Cognitive fusion as a concept is governed by metacognitive processes, in which thought dominates and directs behavior, perceived by the psychotic patient as valid and in line with reality. In this way, vulnerability develops at the cognitive, affective and behavioral level as a factor in maintaining or aggravating psychopathological phenomena(24,25).

The rigidity resulting from cognitive fusion is problematic due to the imperative character resulting from thoughts and the character of absolute truth. This rigidity and narrowing greatly restricts the patient’s options and freedom, not being able to observe the thought from the outside. This phenomenon is highlighted in the patient with psychotic symptoms with either positive or negative symptoms. The symptomatology has an absolute truth character, having no other possibility or perspective due to the implicit character of the thoughts taking the aspect of a network(26).

We obtained a statistically important difference between patients with psychosis and the control group, in the direction of a cognitive fusion congruent with the symptomatology. The psychotic patient is incapable of the alternative perspective and the ability to defuse a certain belief in the ideational or perceptual plan, which maintains the symptoms and produces a progressive aggravation(27).

The combination of cognitive fusion and unconditional acceptance is a maladaptive factor, which indicates an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms, due to the lack of a viable alternative that the patient can apply in order to reduce the stress generated by cognitive fusion(28).

Limitations

Our study presents several limitations. One of them is represented by the small number of participants in both groups (N=20). For this reason, other factors which were not taken into account in our research can be present and can explain the results obtained. In addition, it is possible that the target group (the psychiatric patients) present higher age variability. The control group is composed of students, therefore the age range is shortened for this group.

Conclusions

Cognitive fusion is a mechanism that is found more in psychotic patients than in controls. The present work highlights the need for more studies regarding the field of cognitive fusion and unconditional self-acceptance, for a better understanding of the factors that trigger or maintain psychotic symptoms.

Certifications

The authors confirm that the article has not been published or sent for publication in another journal.

All participating authors approved the content of the paper.

The article is for scientific purposes only, not serving material personal interests.

The subjects were included in the study after accepting the informed consent.

Bibliografie

-

Gaebel W, Zielasek J. Focus on psychosis. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015; 17:9-18.

-

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington. 2013.

-

Popov S. When is Unconditional Self-Acceptance a Better Predictor of Mental Health than Self-Esteem? J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2018; 37: 251-261.

-

Jibeen T. Unconditional Self Acceptance and Self Esteem in Relation to Frustration Intolerance Beliefs and Psychological Distress. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2017; 35: 207-221.

-

Oltean H-R, David DO. A meta-analysis of the relationship between rational beliefs and psychological distress. J Clin Psychol. 2018; 74: 883-895.

-

Luoma JB, Hayes SC, Walser RD. Learning ACT: An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual for Therapists. New Harbinger Publications. 2017; 94-97.

-

Gold DB, Wegner DM. Origins of ruminative thought: Trauma, incompleteness, nondisclosure, and suppression. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1995; 25, 1245–1261.

-

Wegner DM, Zanakos S. Chronic thought suppression. Journal of Personality. 1994; 62, 615–640.

-

Morrison AP, Baker CA. Intrusive thoughts and auditory hallucinations: A comparative study of intrusions in psychosis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000; 38, 1097–1106.

-

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. Guilford Press, New York, US. 1999.

-

Hayes SC, Pistorello J, Levin ME. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. Couns Psychol. 2012; 40, 976–1002.

-

Chamberlain J, Haaga D. Unconditional Self-Acceptance and Psychological Health. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2001; 19. 163-176.

-

Gillanders DT, Bolderston H, Bond FW, Dempster M, Flaxman PE, Campbell L, Kerr S, Tansey L, Noel P, Ferenbach C, Masley S, Roach L, Lloyd J, May L, Clarke S, Remington R. The development and initial validation of The Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behavior Therapy. 2014; 45, 83-101.

-

Williams J, Bucci S, Berry K, Varese F. Psychological mediators of the association between childhood adversities and psychosis: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018; 65: 175-196.

-

Sönmez N, Romm KL, Østefjells T, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy in early psychosis with a focus on depression and low self-esteem: A randomized controlled trial. Compr Psychiatry. 2020; 97: 152157.

-

Pyle M, Morrison AP. Internalised stereotypes accross ultra-high risk of psychosis and psychosis populations. Psychosis. 2017; 9(2): 1-9.

-

Soflau R, David DO. The Impact of Irrational Beliefs on Paranoid Thoughts. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2019; 47(3): 270-286.

-

Lawlor C, Hepworth C, Smallwood J, Carter B, Jolley S. Self-reported emotion regulation difficulties in people with psychosis compared with non-clinical controls: A systematic literature review. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020; 27(2): 107-135.

-

Gergel T, Iacoponi E. Psychosis and identity: Alteration or loss? J Eval Clin Pract. 2017; 23(5): 1029-1037.

-

Lysaker PH, Gagen E, Klion R, et al. Metacognitive Reflection and Insight Therapy: A Recovery-Oriented Treatment Approach for Psychosis. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020; 13: 331-341.

-

Jordan G, MacDonald K, Pope MA, Schorr E, Malla AK, Iyer SN. Positive Changes Experienced After a First Episode of Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr Serv. 2018; 69(1): 84-99.

-

Peters E, Ward T, Jackson M, et al. Clinical, socio-demographic and psychological characteristics in individuals with persistent psychotic experiences with and without a “need for care”. World Psychiatry. 2016; 15(1): 41-52.

-

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. The Guilford Press A Division of Guilford Publications. 1999; 13-15.

-

Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD, Hayes SC. Is it the symptom of the relation to it? Investigating potential mediators of change in acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis. Behavior Therapy. 2010; 41(4), 543–554.

-

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed). New York: Guilford Press. 2011.

-

Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KM, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire‐II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy. 2011; 42, 676–688.

-

Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptanceand commitment therapy: Model,processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006; 44, 1–25.

-

Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Ex-periential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996; 64, 1152–1168.