Nodal marginal zone lymphoma (NMZL) is an unfrequent type of indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. NMZL affects mainly the lymph node, but it presents with histologic aspects similar with splenic marginal zone lymphoma or extranodal marginal lymphoma, usually without affecting other structures. Nevertheless, NMZL remains a condition that needs to be further studied in order to better understand its pathogenesis, to better diagnose it and treat the patients with this affliction.

Limfomul nodal de zonă marginală – etiopatologie, diagnostic şi tratament

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma – etiopathology, diagnosis and treatment

First published: 30 martie 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/OnHe.50.1.2020.2963

Abstract

Rezumat

Limfomul nodal de zonă marginală este un tip rar de limfom non-Hodgkin indolent. Acesta afectează în principal ganglionii limfatici, dar prezintă aspecte histologice similare cu limfomul splenic de zonă marginală sau cu limfomul marginal extranodal, de obicei fără a afecta alte structuri. Cu toate acestea, limfomul nodal de zonă marginală rămâne o afecţiune care necesită a fi studiată în contiunare spre a înţelege mai bine patogeneza, pentru a o diagnostica mai repede şi pentru a trata pacienţii cu această afecţiune.

Introduction

According to World Health Organization (WHO) classification, nodal marginal zone lymphoma (NMZL) is “a primary nodal B-cell neoplasm that morphologically resembles lymph nodes involved by MZL of extranodal or splenic types, but without evidence of extranodal or splenic disease”(2,4).

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma represents one of the three subtypes of marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs). The other two are splenic marginal zone lymphomas (SMZLs) and extranodal marginal zone lymphomas(3,4).

All three subtypes belong to the category of indolent lymphomas with B cells. NMZL bares similarities as to the cell of origin, some morphological and pathogenesis aspects with SMZL and MALT lymphomas, but may differ as clinical presentation, biological features, prognostic factors and treatment particularities(3).

The diagnosis of this lymphoma is challenging. The lack of specific markers for this type of lymphoma is making the positive and differential diagnosis difficult.

Epidemiology and etiology

NMZL has the lowest incidence of the marginal zone lymphomas and represents approximately 1% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. It is mostly a disease of the elderly, the majority of the patients at diagnosis being approximately 60-70 years old. It has a higher frequency in men and in non-Hispanic white people(1,5).

A pediatric NMZL entity was recently recognized. It typically presents with asymptomatic localized disease involving predominantly the lymph nodes localized above the diaphragm(1).

The etiology of these types of lymphomas is varied, but there is a constant association with chronic infections and inflammation. In this context, chronic antigenic or autoantigenic immune stimulation leads to lymphoid hypertrophy against which additional oncological events occur, with chromosomal abnormalities leading to the activation of intracellular signaling pathways, thus leading to antigen-independent lymphoproliferation(1,5,7).

There is evidence suggesting an association between NMZL and the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Cryoglobulinemia may be present in these patients. The plasmacytoid differentiation described in some cases could explain the detection of paraprotein immunoglobulin M (IgM)(4,10).

There have been described a few cases of NMZL in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients; some treated only with antiretroviral therapy(10,11).

Autoimmune diseases were found to be associated with NMZL in several studies. The diseases more frequently incriminated were rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, vitiligo, thyroiditis, and Sjögren’s syndrome(3).

Cell of origin

MZL are indolent lymphomas with B cells, which originate in the marginal area of the follicles (spleen, lymph nodes, lymphatic structures attached to the mucous membranes). In NMZl, the primary cell is a mature B cell that has rearranged immunoglobulin genes, useful for detecting these cells in clonality studies. Studies have suggested that NMZL can arise not only from marginal zone B cells, but also from other mature B cells. The vast majority of cases present with somatic hypermutation mostly of IGVH4 gene or in some cases of IGHV3 gene. Thus, a memory B-cell or a post-germinal memory B-cell represents the primary cell(3,4).

Morphology and immunophenotype

NMZL is usually a lymphoma with primary lymph node involvement; in case of advanced stages, it is possible to affect the spline or other lymphoid structures.

Two morphological types have been described: one similar to the lymphoma of the extranodal marginal area, and one similar to the splenic lymphoma of the marginal zone, depending on the characteristics of the identified cells and the distribution of the infiltrate. The immunophenotypic marker IgG is usually positive in NMZL; the immunophenotypic marker IgD is negative in MALT type NZML and positive in splenic type NMZL(20). These B cells are positive for CD19 + CD20 + CD22 +, CD 79 a +, BCL 2 + usually positive. They don’t express CD5 – CD10 – CD23 – CD11c–, CD 43–, cyclin D1–(1-4,12).

Cytogenetic and molecular features

Numerous studies have been carried out in an attempt to identify specific cytogenetic or molecular markers for NMZL, markers useful both as prognostic factors, as well as differentiation lineages from other chronic B lymphoproliferations. Recurrent clonal abnormalities were described, the most frequent being trisomy 3, trisomy 18, trisomy 7, trisomy 12, and del6q(1,3,4).

Gene sequencing has revealed mutations in several genes. The most frequent were somatic mutations in the IGHV genes; other gene mutations were identified in KMT2D (previously known as MLL2), NOTCH2, and KLF2. PTPRD (Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Receptor Type D) is mutated in up to 20% of NMZL(3,8,12).

Diagnosis

Usually, at diagnosis, the patients present with disseminated lymphadenopathy, most frequently in the cervical or abdominal area(1).

Approximately 25% of patients have anemia at diagnosis, with thrombocytopenia present in a smaller percentage(1).

Bone marrow involvement is presented in 30-60% of cases. Other laboratory tests show high levels of lactate dehydrogenase, b2-microglobulin. An M component is present in some cases(1,4,7).

Clinically, in advanced stages, the patients can associate the presence of type B signs – fever, weight loss, drenching sweating(1,3,12).

A complete workup at diagnosis should include history and physical examination, complete blood count, complete biochemistry (including prognostic factors as LDH, B2 microglobulin), bone marrow biopsy, viral screening (HCV, HBV, HIV), CT scan. In order to exclude an extranodal determination, gastroduodenal endoscopy and Helicobacter pylori testing should be performed, plus ear, nose and throat evaluation(1,3,12,13).

The PET-CT examination in evaluating patients shoud be individualized and case adapted, as studies showed variable fluorodeoxyglucose avidity, leading to false-positive results(14,15).

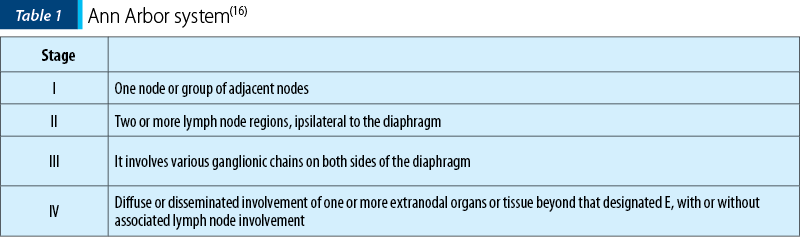

Staging is done based on the revised Ann Arbor system (Table 1)(16).

1. All cases to indicate the absence (A) or presence (B) of systemic symptoms (fever/night sweats/unexplained weight loss).

2. Designation of (E) involvement denotes extranodal extensions or single isolated site of extranodal disease.

3. Designation of (bulky) a single mass > 10 cm or >1/3 of transthoracic diameter(16).

Prognostic factors

NMZL is usually not curable with conventional treatment. While remissions can be obtained, these patients are at risk of relapse.

A specific prognostic score has not been formulated for NMZL. In these patients, usually, the FLIPI (Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index) or the IPI (International Prognostic Index) score is applied. Other factors correlated with poor outcomes are clinical status, age, advanced disease and B symptoms at diagnosis(4,7).

Treatment

NMZL accounts for approximately 2% of the lymphomas(12). Because of the low incidence combined with the few studies performed, there are no standardized protocols.

The criteria for treatment initiation are:

-

advanced stage

-

high LDH

-

bulky mass

-

more than three lymph nodes above 3 cm

-

splenomegaly

-

other symptoms caused by the presence of the disease.

The presence of these criteria defines a high tumor burden(7,13).

In asymptomatic cases and limited stages, the “watch and wait” approach is recommended(1).

Patients with NMZL limited to a single lymph node area are candidates for radiotherapy.

In patients with HCV infection, antiviral therapy may induce remission.

In advanced stages, a combination of immunotherapy and chemotherapy is usually recommended. Rituximab is the choice for immunotherapy. In selected cases, it could be administered in monotherapy, for example in patients who are more mildly symptomatic or have significant comorbidities associated and are poor candidates for the combination therapy(1,7,12,13).

Single-agent rituximab could be administered in a dose if 375 mg/m2 weekly, in a total of four doses, followed or not by the maintenance therapy, which consists of four additional doses administered every two months(1).

In disseminated-stage disease, the combination between immunochemotherapy and chemotherapy is considered an appropriate option.

There is no consensus as to which chemotherapy line would be the best choice. Thus, the decision is individualized and tailored to each case.

In cases of symptomatic disease, with indication of treatment, but with low disease burden or with comorbidities, rituximab alone or in association with chlorambucil (6 mg/m2/d x 6-12 months) or cyclophosphamide (100 mg/day) can lead to good responses(13).

In case of high tumour burden, the treatment should be more aggressive. The options could be R-CVP (cyclophosphamide/vincristine/prednisone), R-bendamustine (BR) or RCHOP (rituximab/ cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone)(4,7,12,13).

Other possible combinations are rituximab/fludarabine (FR) or fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab (FCR)(4,7). There were reported few cases of patients treated with these regimens in clinical trials due to excessive toxicity and high rates of adverse events.

Rituximab in association with lenalidomide is an effective therapeutic option as first-line treatment, phase-2 clinical trials reporting complete responses in 55 to 65 percent of cases(17,18).

Treatment perspectives and novelties

In recent years, there has been an increase interest to use target drugs with high therapeutic effects and limited adverse effects.

Genetic studies have described changes in deregulated pathways including B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, interleukins (IL-2, IL-6, IL-10), integrin signaling (CD40), and cell survival pathways (tumor necrosis factor, transforming growth factor b, and NF-kB). Other possible targeted markers are necrosis factor, NF-kB, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor (PTPR), NOTCH and BCL-2(4,13).

Ibrutinib has showed good results in refractory/relapsed MZL(19).

Other drugs with targeted effects tested in NMZl are everolimus, idelalisib and copanlisib(4). The clinical trials in which these drugs were tested included mostly relapsed/refractory cases.

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has been tested successfully. It was administrated alone or in association with rituximab(1,4).

Venetoclax acts like a BCL-2 inhibitor, a marker that is overexpressed in NMZL, and has shown responses in clinical trials. But data are scarce and were obtained from studies on patients who also had other types of lymphoproliferative disorders(4).

Hematopoietic cell transplantation – there are limited data regarding the administration of intensive chemotherapy, consolidated by stem cell transplantation in NMZ(1).

There have been cited cases that have obtained a fully maintained response for a long time after the transplant. The immediate and late risks of the procedure had to be taken into consideration.

Conclusions

Marginal zone lymphoma remains a relatively unusual and polymorphic disease of B-cells, with a further need for investigations regarding its etiopathogenity, diagnosis and treatment.

NMZL is a distinct identity among small B-cell lymphomas. It is distinct, having unique clinical and morphological features, but also it may present with similarities with the other marginal zone lymphoma subtypes and also follicular lymphomas.

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma is usually confined in lymph nodes. Most cases are diagnosed in advanced stages, but remain asymptomatic and rarely develop the bulky disease.

Immunochemotherapy remains the main choice for the treatment of NMZL. The latest data have shown promising results in understanding the pathological mechanisms and in the implementation of the target medication.

With all the development, there is still an unmet need for clinical trials for patients with MZL, for better defined prognostic factors and for standardized therapeutic guidelines.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Freedman AS, Friedberg JW, Aster JC. Nodal marginal zone lymphoma. uptodate.com., January 2020.

- Quintanilla‐Martinez L. The 2016 updated WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasias. Hematological Oncology. 2017; 35(S1):37–45.

- van den Bran M, et al. Recognizing nodal marginal zone lymphoma: recent advances and pitfalls. A systematic review. Haematologica. 2013; 98(7),1003-1013.

- Thieblemont C, Molina T, Davi F. Optimizing therapy for nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Blood. 2016; volume 127, number 17.

- Khalil MO, Morton LM, Devesa SS, et al. Incidence of marginal zone lymphoma in the United States, 2001-2009, with a focus on primary anatomic site. Br J Haematol. 2014; 165:67.

- Taddesse-Heath L, Pittaluga S, Sorbara L, et al. Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma in children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003; 27:522.

- Zucca E, Arcaini L, et al. Marginal zone lymphomas: ESMO clinical practic guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and diagnosis. Annals of Oncology. 2020; volume 31, issue 1.

- Granai M, Amato T, et al. IGHV mutational status of nodal marginal zone lymphoma by NGS reveals distinct pathogenic pathways with different prognostic implications. Virchows Archiv European Journal of Pathology. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-019-02712-8

- Bertoni F, Rossi D, Zucca E. Recent advances in understanding the biology of marginal zone lymphoma. F1000Res. 2018 Mar 28; 7:406.

- Veneri D, Aqel H, Franchini M, Meneghini V, Krampera M. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in IgM-type monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Am J Hematol. 2004; 77(4):421.

- Baraboutis IG, Marinos L, Lekakis LJ, Papastamopoulos V, Georgiou O, Tsagalou EP, et al. Long-term complete regression of nodal marginal zone lymphoma transformed into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with highly active antiretroviral therapy alone in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Med Sci. 2009; 338(6):517

- Cogliattia S, Bargetzib M, Bertonic F, Hitze F, Lohrif A, Meyg U. Diagnosis and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2016; 146 (SUPPL 216).

- Bron D, Maerevoet M, et al. BHS guidelines for the treatment of marginal zone lymphomas: 2018 update. BHC Practice Guidelines. June 2019; volume 10.

- Weiler-Sagie M, Bushelev O, Epelbaum R, et al. F-FDG avidity in lymphoma readdressed: a study of 766 patients. J Nucl Med. 2010; 51:25.

- Hoffmann M, Kletter K, Becherer A, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) for staging and follow-up of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Oncology. 2003; 64:336.

- Bell DJ, Cheng J, et al. Lugano staging classification. Available at: radiopaedia.org

- Fowler NH, Davis RE, Rawal S, et al. Safety and activity of lenalidomide and rituximab in untreated indolent lymphoma: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014; 15:1311.

- Kiesewetter B, Willenbacher E, Willenbacher W, et al. A phase 2 study of rituximab plus lenalidomide for mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Blood. 2017; 129:383.

- Denlinger NM, Epperla N, William BM. Management of relapsed/refractory marginal zone lymphoma: focus on ibrutinib. Cancer Manag Res. 2018; 10:615-624.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Terapia anti HER-2 în cancerul sânului, o scurtă privire asupra opţiunilor terapeutice disponibile

În această prezentare voi detalia noile terapii disponibile pentru tratarea cancerului de sân cu supraexpresie HER-2 (o oncogenă a familiei EGFR - ...

Tratamentul carcinomului renal metastatic cu terapiile TKI şi mTOR: prezentare de caz

Lucrarea de faţă descrie medicamentele disponibile la ora actuală pentru tratamentul cancerului renal avansat. Acestea sunt reprezentate de mai m...

Mastocitoza – o patologie unică, având multiple faţete

Mastocitoza este o boală rară care a fost definită ca o acumulare anormală de mastocite în unul sau mai multe sisteme de organe. Anterior...

Managementul cancerului de prostată rezistent la castrare

Cancerul de prostată rezistent la castrare (CRPC) este un aspect important al practicii noastre clinice în fiecare zi. Pentru o perioadă foarte lun...