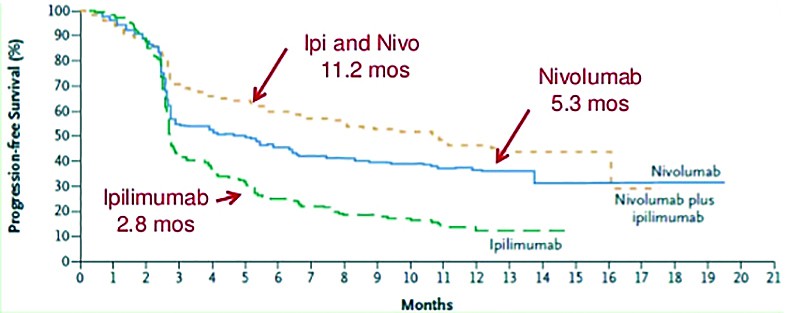

Malignant melanoma (MM) is a neoplasm of the cells that develops from melanocytes. Although belived to be uncommon and despite campaigns that advocate safe sun exposure habbits and early consult for suspicious lesions, the annual incidence is in continuous rise. Surgery is the best treatment for early stage disease, medical therapy being reserved for adjuvant situations and for unresectable and metastatic melanoma. Chemotherapy offers poor response rates. The introduction of immunotherapy brought a great improvement to melanoma treatment (median PFS: 11.2 months for the latest combined treatment) and offered some patients long term survival. This article is a review of the latest clinical trials and therapeutic guidelines regarding immunotherapy in unresectable or metastatic MM.

Schimbarea managementului terapeutic al melanomului malign avansat - imunoterapia

Changing the odds - immunotherapy in malignant melanoma

First published: 07 martie 2017

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

Abstract

Rezumat

Melanomul malign (MM) este o tumoră a celulelor care se dezvoltă din melanocite. Deşi considerat ca având frecvenţă redusă şi în pofida campaniilor care militează pentru o expunere judicioasă la soare şi consult medical al leziunilor suspecte, incidenţa anuală este în continuă creştere. Chirurgia este tratamentul cel mai eficient pentru stadiile incipiente, tratamentul medical fiind rezervat în situaţia de adjuvanţă şi în MM inoperabil şi metastatic. Chimioterapia oferă rate scăzute de răspuns. Introducerea imunoterapiei a adus îmbunătăţiri semnificative în tratamentul melanomului (PFS mediu: 11,2 luni pentru tratament combinat) şi a oferit unor pacienţi supravieţuire pe termen lung. Articolul este o recenzie a ultimelor studii clinice şi a ghidurilor terapeutice privind imunoterapia în MM nerezecabil sau metastatic.

Introduction

Classic agents like dacarbazine (DTIC), chemotherapy combinations (like carboplatin and paclitaxel) or newer agents like temozolomide yield only modest response rates and have very little influence on overall survival (OS). Those patients with BRAF V600E mutation present (approximately 60% of all patients) benefit from treatment with vemurafenib and dabrafenib (median PFS: 5.1 months vs. 2.7 months with DTIC). For patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutation, treatment options are trametinib, a MEK (mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase) inhibitor that yields median PFS of 4.8 months vs. 1.5 months with chemotherapy). The combinations of dabrafenib and trametinib, or the newer cobimetinib (a MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitor) with vemurafenib offer even better PFS.The turning point for melanoma treatment (especially for BRAF mutation negative patients) was first reached in 2011 with the introduction of immunotherapy - ipilimumab (IPI), but the true improvement was yet to come: in 2015, a combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab, which in previously untreated patients boosted a median PFS of over 11 months, something unseen with any other therapy till that moment.

Advantages for immunotherapy are that searching for tumor mutations is less critical and that a number of patients achieve a long term, durable response (long term survivors).

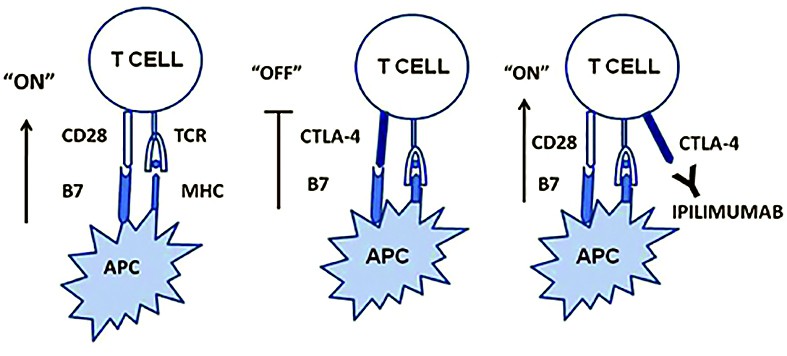

Ipilimumab

Ipilimumab is a CTLA-4 blocker (anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4) approved for unresectable or metastatic melanoma.It is a humanized antibody directed at a down-regulatory receptor on activated T-cells(1).

The mechanism of action is by inhibiting T cell inactivation and permitting their specific cytotoxic effect against melanoma cells.

There have been reported improvements in survival in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with Ipilimumab. In a phase 3 study by Hodi et al., 676 patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma, who progressed on previous treatment, were assigned randomly to receive ipilimumab plus gp100 (glycoprotein 100 melanoma antigen vaccine), ipilimumab alone or gp100 alone.

Ipilimumab was given at a dose of 3 mg/kg and was administered alone or in combination with gp100 every 3 weeks for up to 4 treatment rounds. The median overall survival was 10 months on the arm receiving ipilimumab plus gp100, compared with 6.4 months in those receiving gp100 alone. There was no statistical significant difference in survival in the other ipilimumab arm compared with the ipilimumab-plus-gp100 arm, thus leading to the approval of ipilimumab alone as a treatment for metastatic melanoma(2).

In another phase 3 study, ipilimumab and dacarbazine were compared to dacarbazine and placebo: the survival was improved with 2 months (11 vs. 9 months) in the ipilimumab arm, although grade 3 and grade 4 toxicities were more frequent(3).

The most common side effects of IPI in this study were rash, diarrhea, fatigue, itching, headache, weight loss and nausea. It can also cause autoimmune disease in the digestive system, liver, skin, nervous system, hormone producing glands. It should be avoided by pregnant women.

The MDX010-20 trial evaluated the immune-related adverse events (AE) in 676 patients with MM, assigned to receive either IPI with gp100, IPI plus placebo or gp100 plus placebo(4).

Most immune AE were developed in 12 weeks of initial administration, and they typically passed in 6-8 weeks. From patients receiving IPI in any combination, less than 10% experienced immune related AE (mainly grade 1-2) that wouldn’t resolve after more than 70 days after the last dose.

Most AE were managed keeping patients under observation and with corticosteroids; only 5 patients required infliximab, a TNF (tumor necrosis factor) inhibitor for gastrointestinal AE (ulcerative colitis), with very good response and recovery(4,5).

Comparing immunotherapies with chemotherapy, we can observe that the pattern of response is quite different: while results after chemotherapy may be seen in a few weeks, in immunotherapies we can experience an initial pseudo progression of the targeted lesions, which can last up to 6-8 weeks, a moment from when the response is observed. The phenomenon seems to be explained by immune cells that infiltrate into the tumor. This is only met in patients with MM, in NSCLC the response is closer to the chemotherapy pattern(6).

of “off” signals to T cells, which leads to sustained and elevated adaptive immune responses

(source: http://www.retinalphysician.com)

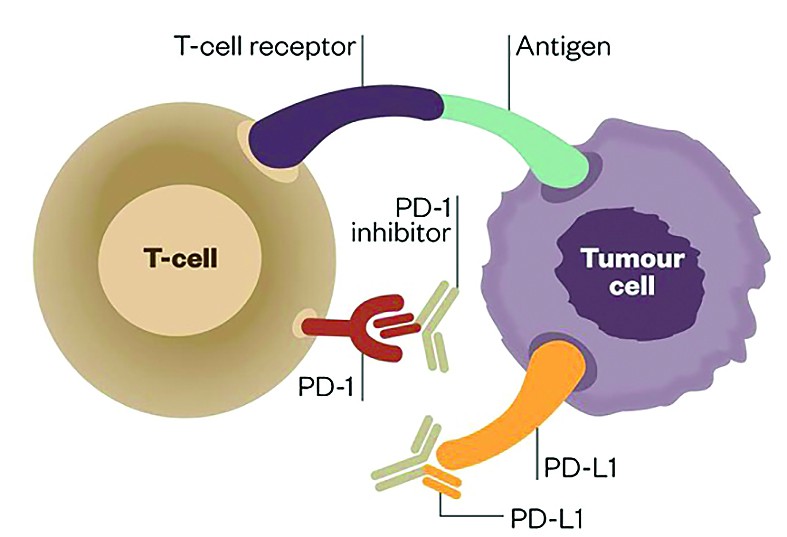

PD-1 inhibitors

PD-1 (programmed cell death-1 protein) and the target PD-L1 (PD-ligand1) are present on the surface of activated T cells. Their interaction inhibits immune response and diminishes T cell antitoxic activity. This process is necessary for keeping immune response in normal limits and prevents normal cells from suffering harm during chronic inflammation. The tumor can bypass T cell mediated cytotoxicity by expressing PD-L1 on tumor surface or on tumor infiltrating immune cells, avoiding immune mediated killing of the tumor cell. Pembrolizumab is the first monoclonal antibody approved for inhibiting PD-1(7), initially approved for unresectable/metastatic melanoma with progression after IPI, and if BRAF V600 positive, a BRAF inhibitor. Registration study showed tumor shrinkage in 24% of patients(8).

After the results from phase 3 KEYNOTE-006 trial, it gained approval for first line use. In the trial, patients with advanced melanoma were randomized to receive either pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks or every 3 weeks, or 4 doses of ipilimumab (3 mg/kg every 3 weeks). Progression-free survival rates for the pembrolizumab groups were 47.3% and 46.4% respectively and 26.5% for ipilimumab(9).

The most common adverse events reported included fatigue, pruritus, rash, constipation, nausea, diarrhea, and decreased appetite. The most serious risks of pembrolizumab are immune-mediated adverse reactions, including pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, and nephritis.

Nivolumab is another PD-1 inhibitor which went through the same steps of approval as pembrolizumab. Registration was done based on a study of patients with unresectable or metastatic MM that have progressed after IPI. Analysis confirmed ORR in 38 of first 120 patients treated with nivolumab versus 5 of 47 patients who received investigator’s choice chemotherapy(10).

Nivolumab is associated with immune-mediated: pneumonitis, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, nephritis and renal dysfunction, rash, encephalitis, infusion reactions, and embryofetal toxicity.

Testing for PD-L1 levels is not required for the treatment of melanoma, as opposed to Pembrolizumab use in NSCLC(11,12).

PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors have therefore been developed to a therapeutic effect (source: The Pharmaceutical Journal)

Nivolumab and ipilimumab combination

The approval of the combination regimen of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in previously untreated patients with BRAF V600 wild-type unresectable or metastatic melanoma came in 2015. Approval was based on results from a phase 2 study - CheckMate-069 study. The study had 142 patients enrolled, 109 had both BRAF wild-type and BRAF mutation-positive melanoma. In patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma, the overall response rate was 61% with the combination regimen, compared with 11% with ipilimumab monotherapy (P <0.001). Additional analysis showed that complete responses were seen in 22% of patients. Partial responses were seen in 43% of the combination group and 11% of the ipilimumab monotherapy group. The combination group had a 60% reduction in the risk of progression compared with ipilimumab alone. Median PFS was 8.9 months with the combination and 4.7 months with ipilimumab alone(13).

Talimogene laherparepvec

In 2015, FDA, and later EMEA approved an oncolytic immunotherapeutic vaccine talimogene laherparepvec (Imlygic). It is a genetically modified, live attenuated herpes simplex type I virus programmed to replicate within tumors and produce the immune stimulatory protein granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). It is indicated for the local treatment of unresectable cutaneous, subcutaneous, and nodal lesions in patients with melanoma recurrence after initial surgery. It is administered by injection into cutaneous, subcutaneous, and/or nodal lesions that are visible, palpable, or detectable by ultrasound guidance(14).The registration study had 436 patients, of which 295 patients treated with talimogene laherparepvec were compared to 141 patients treated with GM-CSF. The primary endpoint was the durable response rate (DRR), defined as the rate of complete response plus partial response continuously lasting ≥6 months and beginning within the first 12 months. Secondary endpoints included overall survival (OR) and the overall response rate (ORR).

“The DRR was greater among patients who received talimogene laherparepvec compared with those given GM-CSF. Of the patients with durable response, 29.1% had a durable complete response and 70.8% had a durable partial response. The median time to response was 4.1 months in the arm receiving talimogene. ORR rate was also higher with talimogene laherparepvec (26.4% vs 5.7%). In all, 32 (10.8%) patients receiving talimogene laherparepvec had a complete response, compared with just one (<1%) patient receiving GM-CSF. The median time to treatment failure was 8.2 months with talimogene laherparepvec and 2.9 months with GM-CSF. Median OS was 23.3 months and 18.9 months, respectively (HR 0.79; P =0.051), which missed by little being statistically significant”(14).

Ipilimumab 2.8 mos Nivolumab 5.3 mos (source: Larkin, NEJM May 31, 2015 Epub)

Conclusion

“The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of advanced melanoma has evolved beyond monotherapies to combination strategies. This approach results in response rates around 60% and superior progression-free survival compared with ipilimumab alone (median: 11.5 versus 2.9 months)”(15).Although these treatments come with a high cost, the invaluable lessons learned from developing and use of these new therapies opens a new perspective on cancer and immunology, enhancing our knowledge and understanding of the disease, and hopefully bringing in time new and more accessible drugs. n

Bibliografie

2. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 19. 363(8):711-23. [Medline].

3. Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 30. 364(26):2517-26. [Medline].

4. Boggs W. Immune-related problems due to ipilimumab emerge early, resolve with discontinuation. Medscape Medical News. February 12, 2013. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/779186. Accessed: March 4, 2013.

5. Weber JS, Dummer R, de Pril V, Lebbe C, Stephen Hodi F. Patterns of onset and resolution of immune-related adverse events of special interest with ipilimumab: Detailed safety analysis from a phase 3 trial in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer. 2013 Feb 7. [Medline].

6. http://cancergrace.org/lung/2015/12/15/gcvl_lu_immunotherapy_response_time_pseudoprogression_concept/

7. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Keytruda for advanced melanoma: first PD-1 blocking drug to receive agency approval [press release]. September 4, 2014. Available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm412802.htm. Accessed: September 9, 2014.

8. Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Hamid O, Kefford R, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2014 Jul 14. [Medline].

9. Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012 Nov. 367(18):1694-703. [Medline].

10. Weber JS, D’Angelo SP, Minor D, Hodi FS, Gutzmer R, Neyns B, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015 Apr. 16(4):375-84. [Medline].

11. Keytruda (Pembrolizumab) prescribing information, 2015.

12. Opdivo (Nivolumab) prescribing information, 2016.

13. Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann K, McDermott D, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 21. 372 (21):2006-17. [Medline].

14. Nelson, R. FDA approves Imlygic, First Oncolytic Viral Therapy in the US. Medscape Medical News. October 27, 2015. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/853345.

15. Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, Amatruda T, Senzer N, Chesney J, et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015 Sep 1. 33 (25):2780-8. [Medline].

16. Spain L, Larkin J. Combination immune checkpoint blockade with ipilimumab and nivolumab in the management of advanced melanoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2016 Feb 1. 1-8. [Medline].

17. Medscape Reference – Malignant melanoma treatment, accessed May 2016.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Carcinomul nazofaringial avansat şi evoluţia cu tratamentul medical

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is one of the most common of head and neck cancers. Most nasopharyngeal carcinoma have a histology cancers of squamous car...

Imunoterapia în cancerul pancreatic - un pas înainte în viitor

De zeci de ani a existat o permanentă preocupare pentru a descoperi relația între tumoră și sistemul imun. Ultimele descoperiri au permis folosirea...