Anxiety is a defining component of the mood of humans from the beginning of mankind to contemporaneity. Its multiple definitions and the numerous research paper dedicated to it reflect the importance of anxiety for human wellbeing. Visual artists cannot escape the challenges of life, therefore they have expressed always the feelings in their work. Artists are even more sensitive than the general population, thus their display of anxiety may be amplified. In this review, we looked for examples of anxiety as expressed in the work of representative visual artists.

Anxietatea în artele vizuale

Anxiety in visual arts

First published: 27 aprilie 2018

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.52.1.2018.1631

Abstract

Rezumat

Anxietatea este o componentă definitorie a dispoziţiei oamenilor, de la începutul umanităţii până în zilele noastre. Numeroasele definiţii, studii şi articole asupra acestui subiect reflectă importanţa anxietăţii pentru starea de bine a indivizilor. Artiştii vizuali nu pot scăpa de provocările vieţii, exprimându-şi mereu sentimentele în operele lor. Ei sunt chiar mai sensibili decât populaţia generală, de aceea exprimarea anxietăţii poate fi amplificată în cazul lor. În cadrul acestui review, sunt prezentate exemple de anxietate exprimată în operele unor artişti vizuali reprezentativi.

There is an extreme generalized and most romantic notion, according to S.B. Kaufman(1), that mental illness and creativity are strongly linked, and that there is not possible to be a genius without being a little mad. Before analyzing this assumption and the scientific evidence that support or challenge it, we are going to present the terms involved more often – the ones related with anxiety disorders.

Anxiety disorders are defined, according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), as a group of disorders that share features of excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioral disturbances. Fear is the emotional response to real or perceived imminent threat, while anxiety is the anticipation of a future threat.

According to the American Psychiatric Organization(2), anxiety is a normal reaction to stress and can be beneficial in some situations. It can alert us to dangers and help us prepare and pay attention. Anxiety disorders differ from normal feelings of nervousness or anxiousness, and involve excessive fear or anxiety. Anxiety disorders are the most common mental disorders and affect nearly 30% of adults at some point in their lives.

Anxiety refers to the anticipation of a future concern and is more associated with muscle tension and avoidance behavior. Fear is an emotional response to an immediate threat and is more associated with a fight or flight reaction – either staying to fight, or leaving to escape danger(3,4).

Anxiety disorders can make people trying to avoid situations that trigger or worsen their symptoms. Job performance, school work and personal relationships can be affected. In general, for a person to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, the fear or anxiety must: a) be out of proportion to the situation or age inappropriate, b) hinder the ability to function normally(1,3,4).

There are several types of anxiety disorders, including: generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, specific phobias, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder and separation anxiety disorder (according to the international disease classification(5)).

The causes of anxiety disorders are currently unknown, but likely involve a combination of factors including genetic, environmental, psychological and developmental. Anxiety disorders can run in families, suggesting that a combination of genes and environmental stresses can produce the disorders(4,5).

There are a number of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, panic disorder, and selective mutism(6). The disorder differs by what results in the symptoms. People often have more than one anxiety disorder(7).

The DSM-5 criteria that are used to diagnose GAD are as follows:

1. The presence of excessive anxiety and worry about a variety of topics, events or activities. Worry occurs more often than not for at least 6 months and is clearly excessive. Excessive worry means worrying even when there is nothing wrong or in a manner that is disproportionate to the actual risk. This typically involves spending a high percentage of waking hours worrying about something. The worry may be accompanied by reassurance-seeking from others.

In adults, the worry can be about job responsibilities or performance, one’s own health or the health of family members, financial matters, and other everyday, typical life circumstances.

2. The worry is experienced as very challenging to control. The worry in both adults and children may shift from one topic to another.

3. The anxiety and worry are associated with at least three of the following physical or cognitive symptoms:

- edginess or restlessness;

- tiring easily – more fatigued than usual;

- impaired concentration or feeling as though the mind goes blank;

- irritability (which may or may not be observable to others);

- increased muscle aches or soreness;

- difficulty sleeping (due to trouble falling asleep or staying asleep, restlessness at night or unsatisfying sleep; many individuals with GAD also experience symptoms such as sweating, nausea, or diarrhea);

- the anxiety, worry or associated symptoms make it hard to carry out day-to-day activities and responsibilities (they may cause problems in relationships, at work, or in other important areas);

- these symptoms are unrelated to any other medical conditions and cannot be explained by the effect of substances including a prescription medication, alcohol, or recreational drugs;

- these symptoms are not better explained by a different mental disorder(6,7).

Researches do agree that mental illness is neither necessary, nor sufficient for a person to be creative and above average as a performer, but there are a lot of studies, started decades ago and still conducted, that showed a connection between a creative brain and some degree of “abnormality”.

Some of the previous studies were criticized because of the small number of subjects involved, and because they based their conclusion on anecdotic facts and on highly specialized samples of top-creators (such as “van Gogh was a strange genius, he cut off his ear – everybody knows this fact”)(8,9,10).

There are many famous people in every field of creative arts without any evidence of mental illness, and also we cannot associate debilitating mental illness with innovation and original ideas.

In this paper we aim to analyze some of the researches that explain the possible connections between creative minds and psychopathology, and also to look at famous works of artists known to have suffered from anxiety (or other related mental disturbances). There is a great and continuous body of research regarding this connections, and the idea attracted both supporters and enemies.

First of all, it is important to underline the fact that there are different levels of creativity which obviously involve different levels of anxiety. There is the day-by-day creativity involving skillful task such as photography, writing for a magazine, and all other kinds of “little” creative behaviours; this kind of creativity is connected with a complete lack of anxiety and it is strongly related with a feeling of wellbeing and personal satisfaction(11,12). It is also well known that art can be therapeutic, being used as art therapy in many psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, there are professional-level expertises in any creative endeavor and eminent creativity – the ultimate forms of creativity and more prone to mental strain leading to anxiety(11).

Simon Kyaga(13) showed that subjects involved in artistic occupations were not more likely to suffer from psychiatric disorders, and a full-blown mental illness did not increase the probability of entering a creative profession, but it was found that people working in creative fields – such as authors, dancers or photographers – were 8% more likely to live with bipolar disorder. Writers were significantly more likely to suffer from this condition and more prone to suicidal thought or even suicide. An interesting finding, though, was that the siblings of patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia were more likely to be involved in creative professions. Researchers studied the role of genetic inheritance in creativity and mental illness. They found that subjects who demonstrated the greatest creativity carried a gene associated with severe mental disorders(14).

William Lee Adams wrote an interesting paper about this, called The Dark side of creativity: Depression + anxiety x madness = Genius? He also showed that psychologists and psychiatrists have been fascinated for decades by the link between creativity and “madness”(15).

There are studies showing that creative persons had an unusual high number of mood disorders. Mark Batey and Adrian Furnham found that the unusual experiences and nonconformist behaviour in schizotypy were significantly related to self-ratings of creativity like confident, individualistic, insightful, original, resourceful and so on; it is also important to underline the fact that schizotypy it is not schizophrenia, and also there is no connection between cognitive disorganization and creative traits(16).

Some neuroscience researchers found an interesting connection between precuneus activity and creative brain. Hikaru Takeuchi et al. showed that the more creative the subjects, the more they had difficulty suppressing the precuneus while engaging in a difficult memory involving task(17). Andreas Fink et al. showed that the right precuneus kept working during the process of idea generation (during a creative task). Normally, this region of the brain deactivates during complex tasks, which is thought to help an individual to focus. The result suggests that creative brains and those with high levels of schizotypy are able to take in more information and are less able to ignore other external stimuli(18). It seems that the key to creative cognition is opening up the flood gates and letting in as much information as possible(11).

One last interesting idea that we will point out is formulated by Mor et al., regarding perfectionism and anxiety. It seems that perfectionism and excessive personal control are associated with debilitating and/or facilitating performance anxiety. The study involved professional performers like actors, dancers or musicians but, in our opinion, it could be extrapolated to any kind of creative process. For decades, studies suggested that individuals with perfectionistic standards are particularly susceptible to feelings of anxiety. Anxiety emerges when the subject perceives a discrepancy between the ideal and the actual self; chronic worriers were especially prone to intrusive cognitions and anxiety because of the discrepancy between their high standards and their actual selves(19).

*

The other side of the connection between anxiety and visual arts is the representation of artists anxiety in their work. Here are some examples.

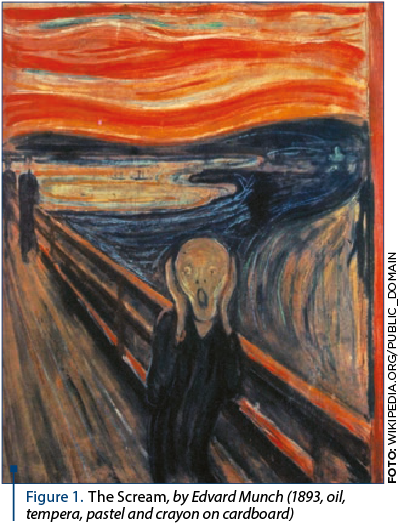

Edvard Munch life was a continuous struggle with anxiety and hallucinations. He created the famous Scream, which he described as a “sinister vision” while standing on the edges of the fiords of Oslo. “The sun began to set – suddenly the sky turned blood red”, he wrote. “I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an endless scream passing through nature”. The interpretation of the painting was obvious – the angst of the modern man. Munch was tormented by anxiety all his life, but he considered it an indispensable driver of his art. “My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art. (…) Illness, insanity and death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle and accompanied me all my life”.

Vincent van Gogh also struggled between genius and madness. “I am unable to describe exactly what is the matter with me. Now and then there are horrible fits of anxiety apparently without cause, or otherwise a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the head... at times I have attacks of melancholy and of atrocious remorse”. The anecdotic “cut of his ear” is known by everybody, sometimes more than his work itself, and there are still controversies regarding the actual event. It is difficult and dangerous to reduce a life of a genius and his creation to a single incident, and it is also unfair to characterize a personality according to this occurrence. It remains the fact that he had a special and maybe strange personality, and it is also probable that this kind of personality marked his paintings; but it is also possible that, like in many other situations, the huge talent of an individual put a “shadow” on his life.

Jackson Pollock suffered form depression and alcoholism, and many of his canvases seem to reflect this long-lasting turmoil.

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti is thought to have suffered from obsessive compulsive disorder or from autism. According to a paper published in 2004(22), Michelangelo’s day-by-day routine may have been due to the disorder. According to descriptions by his contemporaries, the painter was “preoccupied with his own reality”. Most of the male members of his family are recorded to have exhibited similar symptoms. All the evidence of “isolation” from literature, combined with his obvious genius in mathematics and art, led the researchers to believe that today Michelangelo would be considered high functioning on the autism spectrum(22).

Francisco Goya. Biographers have divided the painting experience of Goya into two distinct periods, before and after his illness. The first was characterized by joy and light, the second was characterized by horror and ghosts. In fact, also in the first period, already some of his figures were beginning to appear and were later found to take the form of his nightmares. The dividing line between these two periods was, probably, related to his illness. In late 1700, Goya became seriously ill; he began to suffer from headaches, dizziness, tinnitus, hearing loss, as well as problems with his sight and paresis in the right arm. The causes of this severe illness were often discussed: syphilitic or mercurial encephalopathy (due to anti-syphilitic treatment), the lead contained in the colours that Goya used, or severe atherosclerosis.

At this point, one obviously wonders what relationship exists between his poor health and his painting, and between genius and madness. There is no doubt that the physical disorders – and, in particular, the psychological situation related to them – influenced the artist’s production. But he is inimitable, and the genius exists even without the disease. The severe illness served, maybe, just to transform the tragic elements of his painting in more gloomy and dark ones(23,24).

Georgia O’Keeffe – “the mother of the modernism in USA” – was suffering from anxiety and depression. It seems that O’Keeffe went long periods of time without eating or sleeping. She was so afraid of being unoriginal, that she destroyed all of her paintings shortly before her 30th birthday. She was hospitalized with severe depression, but she got well and wrote to her husband: “I am not sick anymore. Everything in me begins to move”. Shortly after this episode, she found inspiration in the Southwest, and subsequently created many of her haunting landscapes(25).

*

Another aspect of the anxiety in visual arts is the influence of the historical era in which an artist lives, and also the fact that an artist is a creative person, with a great sensitivity, prone to meditation, insight and philosophy, being more than obvious that you will find in his/her work not only pink flowers, but also representations of death, war, pain, struggles, depression, poverty and so on, even he/she was not involved in all of the aforementioned aspects and may or may not be a depressed or anxious personality.

We will use here a well-known example: the Age of Anxiety, from the years after the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War, almost 20 years later; this period reveals the fear, disillusionment, confusion and dismay that Europeans endured(26).

The Guggenheim Museum held an exhibit on postwar art and sculpture in 2010. In attempts to provide stability, many artists returned to “classical art”, complete, with a focus on the beauty of the human form and the ingenuity of man. Others went completely in the opposite direction: Dadaism, “does not mean anything”, and there lies its goal.

Guernica (Pablo Picasso) is one of the most famous Cubist pieces. Picasso depicted the Spanish Civil War that tore Spain apart in the late 1930s as fascist leaders clashed with democratic ones. In fact, the city of Guernica was almost completely destroyed during the war. The painting is a symbol of the ugliness of the war and death, and it is as powerful representation of that turbulent period in history, rather than a sign of Picasso’s anxiety.

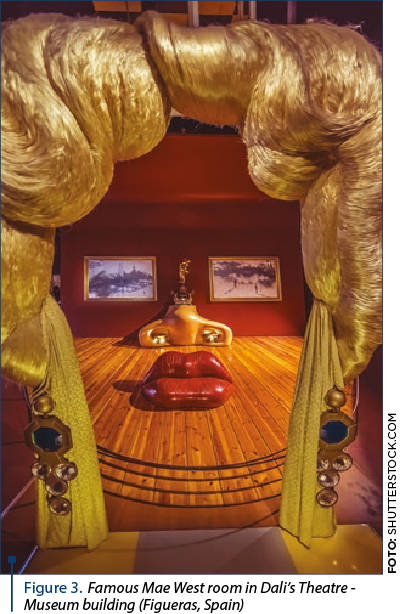

Perhaps one of the most remarkable “anxious artists” of the time was Salvador Dalí. Famous with his unique mustache and odd displays of the human form, Dalí embodied Dadaism: “No more painters, no more writers, no more musicians, no more sculptors, no more religions, no more republicans, no more royalists, no more imperialists, no more anarchists, no more socialists, no more Bolsheviks, no more politicians, no more proletarians, no more democrats, no more armies, no more police, no more nations, no more of these idiocies, no more, no more, NOTHING, NOTHING, NOTHING”. In fact, some artists, like Dalí himself, even morphed from Dadaism to Surrealism, with an emphasis on the subconscious and the impossible, citing the psychology of Freud and Nietzsche(26).

Although Salvador Dalí was not “a normal person”, it is still possible that he consciously created an “artistic” personality. He was famous for his craziness in both his shocking art and persona. Information on his behaviour and art comes from various sources such as his autobiography, literary texts, published interviews with friends, family and the artist himself, letters, and also data on his family history. Dalí was found to meet the diagnostic criteria for several personality disorders, as well as for psychotic illnesses. However, these results should be treated with caution, given the “hall of mirrors” Dalí inhabited and the deliberate persona he projected on to the world(27,28).

The results of a very recent study(29) largely supported the authors first hypotheses: schizotypy was more pronounced in the group of painters than in controls, and also schizotypy was more closely related to the measures of creativity and intelligence in painters. Data suggests that enhanced awareness (one of the so-called non-pathological aspect of schizotypy) is the crucial psychotic-like trait when it comes to the relations between schizotypy and creativity: the highest group differences are found on this trait and it had the highest correlations with creativity measures. This trait represents synesthesia, absorption and immersed contact with reality, thus enabling individuals to have increased awareness of physical objects. Synesthesia can lead to experiences like seeing color in black and white stimuli or sounds, associating sounds or taste with visual stimuli and so on. Also, creativity is often defined as linking unrelated concepts or generating new associations, so the relation between synesthesia and creativity is not surprising(30). However, the link between synesthesia and art is probably bi-directional: synesthesia can be a disposition for creating art, but it can be generated and triggered by studying and training art as well(31). This study also explains some of the ideas and behaviours of the surrealist artists.

In conclusion, is difficult to find a pattern in the correlation between anxiety and visual arts, as the subject is as complex as it could be. The discussion can be often anecdotal because infallible quantification is impossible with such strong and singular personalities who – like Dalí – can also control their “pathological” manifestations and extract from them a source of inspiration and originality. There are a lot of scientific proofs of the relation between mental illness, including anxiety, and creativity, but the theory is still under debate.

Bibliografie

- Kauffman SB. The Real Link between Creativity and Mental Illness. Available at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/beautiful-minds/the-real-link-between-creativity-and-mental-illness/

- American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. Available at: https://psychiatryonline.org/guidelines

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed, Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Crocq MA. The History of Generalized Anxiety Disorder as a Diagnostic Category. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2017; 19 (2): 107–116.

- ICD-10. Version 2010. Available at: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#/F41.2

- Torpy Janet M, Burke AE, Golub RM. Generalized Anxiety Disorder. JAMA. 2011; 305 (5): 522.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.) 2013. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, p. 222.

- Ludwig AM. The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness Controversy. Guilford Press.1996.

- Andreasen NC. The relationship between creativity and mood disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008; 10(2): 251–255.

- Jamison KR. Touched With Fire. Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament. New York, NY: The Free Press. 1993.

- Kaufman JC, Beghetto RA. Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Rev Gen Psychology. 2009; 13 (1): 1-12.

- Ivcevic Z, Brackett M, Mayer JD. Emotional intelligence and emotional creativity. J Personality. 2007; 75 (2): 199-236

- Kyaga S, Landén M, Boman M, Hultman CM, Långström N, Lichtenstein P. Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-year prospective total population study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013; 47(1):83-90.

- Power RA et al. Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder predict creativity. Nature Neuroscience. 2015; 18, 953–955.

- Adams WL. The dark side of creativity: Depression + anxiety x madness = genius? Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/2014/01/22/world/the-dark-side-of-creativity-vincent-van-gogh/index.html

- Batey M, Furnham A. Creativity, intelligence, and personality: a critical review of the scattered literature. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr. 2006; 132(4):355-429.

- Takeuchi H et al. Failing to deactivate: the association between brain activity during a working memory task and creativity. Neuroimage. 2011; 55(2):681-7.

- Fink A et al. Creativity and schizotypy from the neuroscience perspective. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2014; 14(1):378-87.

- Mor S, Day HI, Flett GL, Hewitt PL. Perfectionism, control, and components of performance anxiety in professional artists. Cogn Ter Res. 1995; 19 (2): 207-225.

- Munch E. The Private Journals of Edvard Munch: We Are Flames which Pour out of the Earth. University of Wisconsin Press. 2015.

- Vincent van Gogh. Dragă Theo. Bucureşti, Ed. Art. 2012.

- Arshad M, Fitzgerald M. Did Michelangelo (1475-1564) have high-functioning autism? J Med Biography. 2004; 12:115-120.

- Felisati D, Sperati G. Francisco Goya and his illness. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2010; 30(5): 264–270.

- Buckley PJ. Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes, 1746-1828. Am J Psychiatry. 2009; 166 (3):292.

- Robinson R. Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life. University Press of New England. 1989; pp. 191-193.

- “The Age of Anxiety”. Assessing the impacts of the war on artistic, literary, and existential thought. Available at: http://barnessite.weebly.com/age-of-anxiety-art-literature-and-thought.html

- McKay JP, Hill BD, Buckler J. A History of Western Society, 5 ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1995.

- Murphy C. The link between artistic creativity and psychopathology: Salvador Dalí. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009; 46 (8), 765-774.

- Mededovic J, Djordjevic B. Schizotypal traits in painters: Relations with intelligence, creativity and creative productivity. Psihologija. 2017; 50(3): 341–355.

- Ramachandran VS, Hubbard EM. The Phenomenology of Synaesthesia. J Consciousness Studies. 2003; 10 (8): 49–57.

- Rothen N, Meier B. Higher prevalence of synaesthesia in art students. Perception. 2010; 39(5):718-20.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Noi perspective în ICD-11 pentru tulburările anxioase, tulburările obsesiv-compulsive şi tulburările asociate stresului

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) reprezintă sistemul de codare standard al tuturor bolilor. Noua versiune, ICD-11, a fost publica...

Canabidiolul – zeci de ani de cercetare şi utilizările clinice actuale

Deşi majoritatea cercetărilor referitoare la canabis s-au concentrat asupra delta-9-trans-tetrahidrocanabinolului (THC), recent alte componente ale...

Realitatea virtuală imersivă în psihoterapia anxietăţii şi reabilitarea oculară. O abordare transdisciplinară

Realitatea virtuală imersivă (iVR) reprezintă nu numai o intervenţie indicată de ghidurile terapeutice în anumite tulburări de anxietate, ci şi o i...

Dialog nosografic între ICD-10, DSM-5 şi ICD-11 pe tema tulburărilor de dispoziţie

Spre deosebire de ICD-10, ICD-11 este mai apropiat de ghidurile de tratament şi este mai solid fundamentat pe cercetări biologice, fără însă a avea...