Adenomioza вҖ“ algoritm de diagnostic, tratament Еҹi implicaЕЈii obstetricale

Algorithm for diagnosis, treatment and obstetric implications of adenomyosis

Abstract

Adenomyosis continues to be a challenge for gynecologists, although the possibilities for diagnosis have greatly progressed. Modern imaging techniques (ultrasound, MRI) have led to precise diagnostic criteria and also the various therapeutic methods make total hysterectomy to be forgotten as the only solution for patients with adenomyosis. The anamnesis reveals dysmenorrhea (often primary), adding the progressive increase of the menstrual blood amount (up to menorrhagia). The patient may also report chronic pelvic pain, meaning dyspareunia in 10% of cases. The imaging examinations are the most valuable in helping to diagnose this pathology, because the image reflects the histopathological changes in the uterus. The most important feature of adenomyosis is the disturbance or deformation of the junctional zone (JZ), the functional layer between the endometrium and the myometrium. The ultrasound aspect depends on the variable proportion between the endometrial glandular structures, the endometrial stroma and the hypertrophic muscle elements inside the lesion. The ultrasound signs can be direct or indirect. It is considered that the presence of at least three signs outlines the imaging diagnosis of adenomyosis. We present the diagnostic ultrasound criteria as presented in the Consensus of the MUSA Group (Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment), 2015. For the imaging diagnosis of adenomyosis, it is considered that transvaginal ultrasound and MRI are complementary examinations. Regarding the obstetric implications of adenomyosis, the subfertility of patients with adenomyosis is discussed, with repeated failures of the assisted reproductive techniques, probably through exaggerated peristalsis at the level of JZ. During the pregnancy of patients with adenomyosis, we observe: abdominal pain, unrelated to increased contractile activity, premature contractile activity with abortion in the second trimester or even premature birth; imaging aspect of false abnormal insertion of the placenta (abnormally adherent), uterine rupture (several cases described in literature). We present some conclusions, from personal case studies – a retrospective clinical study combined with a prospective observational study.Keywords

adenomyosisultrasoundMRIobstetric complicationsRezumat

Adenomioza continuДғ sДғ fie o provocare pentru ginecologi, deЕҹi posibilitДғЕЈile de diagnostic au progresat foarte mult. Tehnicile imagistice moderne (ecografia, rezonanЕЈa magneticДғ nuclearДғ) au condus la criterii diagnostice precise, iar paleta mai largДғ terapeuticДғ face uitatДғ histerectomia totalДғ ca unicДғ soluЕЈie pentru pacienta cu adenomiozДғ. Anamneza relevДғ dismenoree (de cele mai multe ori primarДғ), la care se adaugДғ creЕҹterea progresivДғ a cantitДғЕЈii de sânge menstrual pierdute (pânДғ la menoragie). Pacienta mai poate relata durere pelvianДғ cronicДғ, iar în 10% din cazuri existДғ dispareunie. Examenele imagistice sunt cele mai valoroase în conturarea diagnosticului, deoarece imaginea reflectДғ modificДғrile histopatologice de la nivelul uterului. Cea mai importantДғ caracteristicДғ a adenomiozei este perturbarea sau deformarea zonei joncЕЈionale (ZJ), stratul funcЕЈional dintre endometru Еҹi miometru. Aspectul ecografic depinde de proporЕЈia variabilДғ dintre structurile gandulare endometriale, stroma endometrialДғ Еҹi elementele musculare hipertrofice din interiorul leziunii. Semnele ecografice pot fi directe sau indirecte. Se considerДғ cДғ prezenЕЈa a cel puЕЈin trei semne contureazДғ diagnosticul imagistic de adenomiozДғ. PrezentДғm criteriile ecografice de diagnostic aЕҹa cum au fost conturate în Consensul Grupului MUSA (Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment), 2015. Pentru diagnosticul imagistic al adenomiozei se considerДғ cДғ ecografia transvaginalДғ Еҹi RMN-ul sunt examinДғri complementare. În ceea ce priveЕҹte implicaЕЈiile obstetricale ale adenomiozei, se discutДғ despre subfertilitatea pacientelor cu adenomiozДғ Еҹi despre eЕҹecuri repetate ale tehnicilor de reproducere umanДғ asistatДғ (RUA), probabil prin peristaltica exageratДғ la nivelul ZJ. În evoluЕЈia sarcinii la pacienta cu adenomiozДғ pot apДғrea: algii abdominale, nelegate de activitatea contractilДғ crescutДғ, activitate contractilДғ prematurДғ cu avort în trimestrul al doilea sau naЕҹtere prematurДғ; aspectul imagistic de falsДғ inserЕЈie anormalДғ a placentei (anormal aderentДғ); ruptura uterinДғ (sunt descrise câteva cazuri în literaturДғ). Pe baza cazuisticii personale – un studiu clinic retrospectiv, combinat cu un studiu observaЕЈional prospectiv, prezentДғm câteva concluzii.Cuvinte Cheie

adenomiozДғecografieRMNcomplicaЕЈii obstetricaleIntroduction

First described in 1860 as cystosarcoma adenoidis uterinum, or internal endometriosis, by Carl von Rokitansky, professor of anatomy and pathology at the University of Vienna(1), adenomyosis continues to be a challenge for gynecologists, although the possibilities for diagnosis and treatment have progressed a lot. Modern imaging techniques (ultrasound, nuclear magnetic resonance) have led to some precise diagnostic criteria and the vaВӯrious therapeutic methods make total hysterecВӯtomy forВӯgotВӯten as the only solution for the patient with adeВӯnoВӯmyosis.

Diagnostic algorithm

Recently, it was considered that adenomyosis is the prerogative of the patient over 35 years old, revealing itself by dysmenorrhea and progressive menorrhagia. However, thorough transvaginal ultrasounds may reveal focal adenomyosis in young patients as well(2). For patients over 30 years old, adenomyosis has also a great significance in terms of fertility and the favorable evolution of a future pregnancy(3).

Materials and method

We present the diagnostic criteria and the therapeutic algorithm for adenomyosis, as well as its possible obstetric implications. The diagnosis is based on anamnesis, clinical examination and paraclinical investigations.

The anamnesis reveals often primary dysmenorrhea combined with a progressive increase of menstrual blood amount (up to menorrhagia). The patient may also report chronic pelvic pain, meaning dyspareunia in 10% of cases. The patient may have a history of diagnoses and treatments for endometriosis, endometrial polyps or even endometrial hyperplasia. There can be some association between these three diseases. One of the most common associations is with uterine fibroma or fibromatosis. There may be a history of infertility or failure of assisted human reproduction (AHR) procedures(4). All these elements must alert the clinician, suggesting a possible adenomyosis.

The clinical examination may detect a slightly enlarged uterus or even a more globular appearance of this organ. The uterus can sometimes be painful when mobilized. Imaging examinations are the most valuable in establishing the diagnosis, because the image reflects histopathological changes in the structure of uterus. Thus, adenomyosis is represented by the proliferation of endometrial glands and stroma in the myometrium, which becomes hypertrophic and/or hyperplastic, resulting lesions with imprecise boundaries. Adenomyosis can be localized (focal adenomyosis) or dispersed (diffuse adenomyosis, generally with faster onset, after the age of 20 years old). Cystic transformation (cystic adenomyoma) is less common. The most important feature of adenomyosis is the disturbance or deformation of the junctional zone (JZ), the functional layer between the endometrium and myometrium. The JZ usually measures less than 5 mm and it is under hormonal influence. It provides uterine peristalsis (reduced in the luteal phase) and it is involved in blastocyst nidation and trophoblastic invasion.

To define adenomyosis from a histopathological point of view, the penetration of the endometrium into the myometrium at a depth of at least 2.5 mm below the basal endometrium or more than a quarter of the thickness of the endometrial-myometrial junctional area (both being diagnostic criteria) has to be described.

The ultrasound aspect depends on the variable proportion between the endometrial glandular structures, the endometrial stroma and the hypertrophic muscle elements inside the lesion. The ultrasound signs can be direct or indirect. It is considered that the presence of at least three signs outlines the imaging diagnosis of adenomyosis. We present the diagnostic ultrasound criteria as presented in the Consensus of the MUSA Group (Morphological Uterus Sonographic Assessment)(5).

The direct ultrasound signs are:

1. Subendometrial microcysts вҖ“ anechoic images of 2 or 4 mm, nonvascularized, representing the pathognomonic sign. These correspond to cystic dilated glands. If the examination is done during menses or immediately postmenstrual, the images may be more echogenic. A small intracystic hemorrhage may occur.

2. Nonhomogeneous appearance of the myometrium, which may present intramiometric hyperechoic linear striations вҖ“ вҖңvenetian blinds signвҖқ, subendometrial hyperechoic areas, insufficiently delimited pseudonodular hypoechoic areas, without mass effect on the endometrium, images of вҖңsubendometrial budsвҖқ.

3. Irregular endometrium-myometrium junction, poorly defined or thickened.

The indirect ultrasound signs are those that result from the reactive hypertrophy of the myometrial fibers around the ectopic endometrial glands:

1. Uterus with regular contour, globular (transverse and longitudinal diameters substantially equal), without external deformations.

2. Asymmetrical myometrial walls (usually the thickest is the posterior one). The walls are measured in the sagittal plane, perpendicular to the endometrium, from the serosa to the endometrium, including the junctional zone.

3. Linear, radial vascularization that crosses the myometrium in full adenomyosis lesion (important differential diagnosis with fibrous nodules). The use of the power Doppler technique is recommended. Vascular resistance is assessed at the myometrial level (IR 0.56Вұ0.12) and at the level of the uterine arteries (lower compared to that of the myometrium).

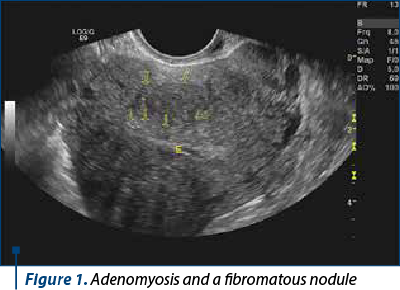

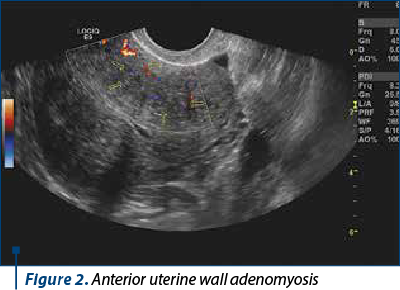

The ultrasound diagnosis is more difficult in patients with other types of lesions (fibromatous nodules or diffuse fibromatosis) вҖ“ Figures 1 and 2.

В

Three-dimensional ultrasound can reveal additional imaging details, because the uterus can also be evaluated in the coronal plane. The junctional zone appears as a hypoechoic halo surrounding the endometrium. A junctional zone of more than 8 mm or inhomogeneous, with differences greater than 4 mm between different areas, is a suggestive element. However, the junctional area is much better assessed by MRI examination(6).

Imaging diagnosis by pelvic MRI

For the imaging diagnosis of adenomyosis, it is considered that transvaginal ultrasound and MRI are complementary examinations. However, MRI is preferred to be performed at the end of the proliferative period вҖ“ at the beginning of the secretory period, when the examination conditions of the junctional area are optimal. The MRI criteria for the diagnosis of adenomyosis are the following:

1. Diffuse, poorly delimited or stretched junctional zone (more than 14 mm).

2. JZ with poorly defined or indistinguishable edges from the myometrium.

3. Outbreaks with a signal of increased intensity, of a few millimeters, in JZ, on T2- or T1-weighted images (corresponding to heterotopic endometrial tissue, cystic dilatations of the endometrial glands or microhemorrhages).

4. JZ with a thickness of 11-13 mm, with poorly defined edges and foci of high intensity.

Two of the first three criteria or the fourth criterion are required for the MRI diagnosis of adenomyosis. Also, the MRI criterion for excluding the diagnosis of adenomyosis is a JZ below 8 mm. When MRI exam is performed, adenomyosis must be differentiated from pathologies that can mimic it. These are: physiological myometrial contractions, myometrial extension of a pelvic endometriosis, uterine sarcomas or uterine metastases.

Therapeutic conduct

1. The first therapeutic option is represented by hormonal treatment: combined (estrogen-progesterone), progesterone-only pill (POP), semisynthetic progestogens, levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG IUD)(7), danazol by intracervical administration or endouterine administration through a uterine device, aromatase inhibitors (letrozole). All these treatments can relieve menorrhagia but have no effect on pain. If LNG IU is used, the phenomenon of tachyphylaxis has been described. The device must be changed earlier (from five years to about three years)(7). After stopping the medication, the symptoms reappear after an average of six months.

2. GnRH analogues are considered the second-line medication due to the side effects (induction of artificial menopause), although their effectiveness on adenomyosis is very good.

3. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) control dysmenorrhea very well, but they cannot control the bleeding.

4. Selective embolization of the uterine arteries has short-term effects, with recurrences in two years. However, this kind of treatment is very useful for patients who have subfertility or reproductive plans. It should be mentioned that the MRI postembolization control shows a decrease in size of the adenomyosis foci, a decrease in the overall size of the uterus, but no change in the thickness of the ZJ(8).

5. The surgical methods are laparoscopic adenomyoВӯmectomy or laparatomy. It may sometimes require uterine reconstruction, which burdens the obstetrical future(9).

6. Ablation of adenomyotic foci with high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), guided by MRI (there is a limited experience internationally, but it seems to be an option for patients who want to be pregnant)(10).

7. Total hysterectomy for patients who no longer want children and who do not accept another type of treatment.

Obstetric implications of adenomyosis

We discuss about the subfertility in patients with adenomyosis and the repeated failures of assisted human reproduction techniques (AAR), probably by exaggerated peristalsis at the level of ZJ(11). These findings are the result of research in assisted human reproduction centers, which have many patients with endometriosis, but who frequently associate adenomyosis.

If adenomyosis is diagnosed or if there is an adenomyosis-endometriosis combination, the treatment with Gn RH analogues, danazol or combinations is recommended for three to six months before a stimulation protocol. LNG IUD should be used for 12 months before stimulation/insemination. Ablative surgeries are not recommended. The rate of pregnancy loss is 30% in patients with adenomyosis compared with 13% in those without IVF/ICSI procedures(11).

In the evolution of pregnancy combined with adeВӯnoВӯmyoВӯsis, there may appear abdominal pain, unrelaВӯted to increased contractile activity, premature contractile activity with abortion in the second trimester or even premature birth; the imaging aspect of false abВӯnorВӯmal insertion of the placenta (abnormally adheВӯrent), uterine rupture (several cases described in liteВӯraВӯture)(12).

It is also considered that patients with adenomyosis have a deeper inserted placenta, which would lead to a higher risk of preeclampsia(13). The association between increased uterine contractility and dystocic presentations may explain the increased risk of premature birth(14).

Results

From our personal case study (a retrospective clinical study, between 1.01.2016 and 31.12.2020), combined with a prospective observational study (1.01.2018-31.12.2020), we present some conclusions.

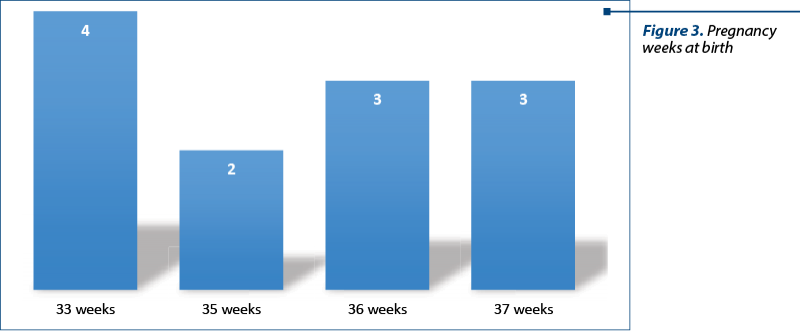

In the retrospective study, we included 12 patients, aged 33-41 years old, all with imaging-suggested adenomyosis more than one year postpartum (average: 16 months), under the conditions of a routine control. Resuming the anamnestic data from the observation sheets, we noted the following: among these patients, eight had a history of infertility, and three had been operated for endometriosis. Among the patients with infertility, three managed to get pregnant after an in vitro fertilization procedure, one being performed by ICSI. All had at least one hospitalization during pregnancy, for вҖңpainful uterine contractionsвҖқ, which did not yield to antispasmodics, but only to suppositories with indomethacin (two to three suppositories daily) and/or infusions with paracetamol. All patients gave birth between 33 and 37 weeks of pregnancy (WP) вҖ“ four at 33 WP, two at 35 WP, three at 36 WP and three at 37WP, in all cases with a premature rupture of the membranes (Figure 3). Four of the newborns had intrauterine growth retardation.

В

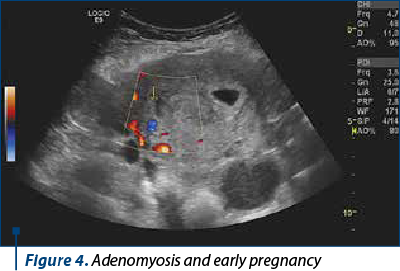

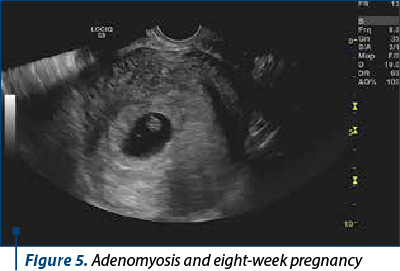

In the prospective observational study, we monitored seven patients with suspected ultrasound adenomyosis, according to MUSA standards (Figures 4 and 5).

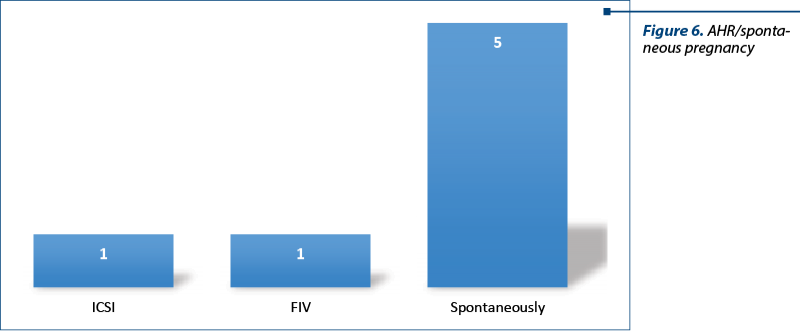

One of them obtained the pregnancy through ICSI (history of operated endometriosis), one with IVF, and the other five spontaneously (Figure 6).

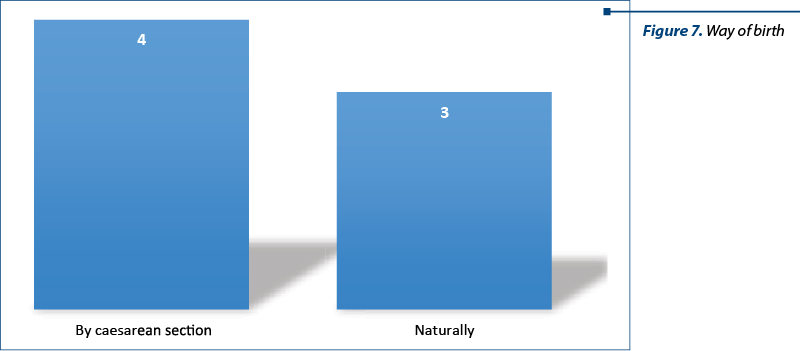

Warned of the painful episodes, we administered indomethacin as the drug of choice and antispasmodics as second-line drugs. Paracetamol infusion was also used. Knowing the risk of premature birth, we systematically performed the prophylaxis of neonatal respiratory distress. Four patients gave birth by caesarean section (two breech presentations, one case of preeclampsia and one case of fetal pelvic disproportion), and three gave birth naturally (Figure 7).

In the operated patients, we observed intraoperatively a globular aspect of the uterus, but without special hemostasis problems. All of them had characteristics of uterine subinvolution early postpartum, without hemorrhagic or infectious problems.

Discussion

Although the studied groups were small, we can observe the association of adenomyosis with infertility and the need to use assisted human reproduction techniques. Once the pregnancy is obtained, it is important to emphasize the frequency of painful episodes, which are often interpreted as increased uterine contractility. The following treatments have been proposed for pregnancy symptoms:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) вҖ“ indomethacin (it inhibits prostaglandin synthesis; it appears that at the chorionic-decidual interface the decidual cells are larger in patients with endometriosis and adenomyosis and the inflammation cascade is activated). From our experience, we consider that NSAIDs are the first drugs to be used in pregnant women who have been diagnosed with adenomyosis. On the other hand, NSAIDs should be started when antispasmodic medication is not effective within a few hours with diffuse abdominal pain without any other cause.

The administration of high doses of natural or semi-synthetic progesterone in patients with diagnosed adenomyosis may have a beneficial effect in prolonging pregnancy and delaying the onset of painful symptoms(14).

Antiplatelet drugs are also proposed in literature for inhibiting the production of thromboxane A2 (ozagrel). Also, studies performed on rats show promising results for resveratrol(13,14).

Conclusions

Adenomyosis, although diagnosed much more frequently today due to imaging advances, remains an entity still misunderstood, with a sufficiently high incidence and with often subtle symptoms, as well as with important implications regarding the reproductive area and the obstetric outcome.В

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

Molitor JJ. Adenomyosis: a clinical and pathological appraisal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110(2):275-84.

Ryna GL, Stolpen A, Van Voorhis BJ. An unusual cause of adolescent dysmenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1017-22.

Taran FA, Weaver AL, Coddington CC, Stewart EA. Understanding adenomyosis: a case control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4):1223-8.

Zhang Y, Yu P, Sun F, Li TC, Cheng JM, Duan H. Expression of oxytocin receptors in the uterine junctional zone in women with adenomyosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(4):412-8.

Van den Bosch T, Dueholm M, Leone FP, Valentin L, Rasmussen CK, Votino A, Schoubroeck DV, Lamdolfo C, Installe AJF, et al. Terms, definitions and measurements to describe features of myometrium and uterine masses: a consensus opinion from MUSA group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(3):284-98.

Champaneira R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and MRI for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(11):1374-84.

Shaaban OM, Ali MK, Sabra AM, Abd El Aal DE. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine

versus a low dose combined oral contraceptive for treatment of adenomyotic uteri: a randomized clinical trial. Contraception. 2015;92(4):301-7.

Nijenhuis RJ, Smeets AJ, Morpurgo M, Brujin AM, Smink M, Hehenkampf WJK, Reuwer PJH, Lohle PNM, Rooji WJV. Uterine artery embolisation for symptomatic adenomyosis: three-year clinical follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40(9):1644-350.

Huang X, Huang Q, Chen S, Zhang J, Kaiqing L, Zhang X. Efficacy of laparoscopic adenomyomectomy using double-flap method for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:24.

Hai N, Hou Q, Ding X, Dong X, Jin M. US-guided transcervical radiofrequency ablation for symptomatic uterine adenomyosis. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1069):20160119.

Tomassetti C, Meuleman C, Timmermann D, D’Hooghe T. Adenomyosis and subfertility: evidence of association and causation. Semin Reprod Med. 2013;31(2):101-8.

Juang CM, Chou P, Yen MS, Twu NF, Horng HC, Hsu WL. Adenomyosis and risk of preterm delivery. BJOG. 2007;114(2):165-9.

Hashimoto A, Iriyana T, Sayama S, Nakayama T, Komastsu A, Miyauchi A, Nishii O, Nagamatsu T, Osuga Y, Fujii T. Adenomyosis and adverse perinatal outcomes: increased risk of second trimester miscarriage, preeclampsia and placental malposition. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(3):364-9.

Razavi M, Maleki-Hajiagha A, Sepidarkish M, Rouholamin S, Almasi-Hasiani A, Rezaeinejad M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of adverse pregnancy outcomes after uterine adenomyosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;145(2):149-57.