Gallbladder adenomyomatosis – 42 years of experience

Adenomiomatoza veziculară – 42 de ani de experienţă

Abstract

Introduction. The year 1882 marked the beginning of biliary surgery, the year in which Carl Langenbuch performed the first cholecystectomy. Thus, cholecystectomy has become a current surgery, especially for vesicular lithiasis, with its acute and chronic manifestations, but also for its complications. Materials and method. In 1931, it was introduced another indication for cholecystectomy – cholecystitis glandularis proliferans. Thereafter, the number of articles regarding this disease increased considerably over the years 1950-1980. In Romania, this pathology – in fact, a vesicular dysplasia – was recognized under the name of cholecystosis. Results. The authors analyzed a batch of 532 cholecystoses, most of them non-lithiasic: adenomyomatoses and cholesteroloses, operated over a period of 42 years (1974-2016). The authors also present an analysis of the types of cholecystoses encountered, along with their clinical expression and the postoperative evolution. Conclusions. Beginning with 1994, the surgical treatment has been performed using laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 98% of the cases. The surgical indication is determined on clinical criteria and on ultrasound imaging.Keywords

gallbladder adenomyomatosisnon-lithiasic cholecystosischolesterolosesRezumat

Introducere. 1882 este anul care a marcat începutul chirurgiei biliare şi anul în care Carl Langenbuch a efectuat prima colecistectomie. Astfel, colecistectomia a devenit o operaţie curentă, dedicată în special litiazei veziculare, cu manifestările ei acute şi cronice, dar şi complicaţiilor ei. Materiale şi metodă. În anul 1931 a apărut o altă indicaţie a colecistectomiei – colecistita glandulară proliferativă. Ulterior, numărul publicaţiilor destinate acestei patologii a crescut considerabil pe parcursul anilor 1950-1980. În România, această patologie – de fapt, o displazie veziculară – a fost cunoscută sub numele de colecistoză. Rezultate. Autorii analizează un lot de 532 de colecistoze, majoritatea nelitiazice: adenomiomatoze şi colesteroloze, operate pe parcursul a 42 de ani (1974-2016). De asemenea, este prezentată o analiză a tipurilor de colecistoze întâlnite, a modalităţilor de exprimare clinică şi a evoluţiilor postoperatorii. Concluzii. Din anul 1994, tratamentul chirurgical s-a realizat prin colecistectomie laparoscopică în 98% din cazuri. Indicaţia chirurgicală se stabileşte pe criterii clinice şi în funcţie de imagistica ecografică.Cuvinte Cheie

adenomiomatoză vezicularăcolecistită alitiazicăcolesterolozeIntroduction

Gallbladder adenomyomatosis was initially named cholecystitis glandularis proliferans by King and Mak Callum in 1931. These two authors described the lesion as a “diffuse thickening of the wall of chronically inflamed gallbladder, characterized by excessive proliferation of and invasion of the wall by epithelium, forming crypts, with dilatation of some of these crypts to form cysts”(1). The histological description 91 years ago still remains valid. The described anatomopathological lesions occur around the Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses. Thus, cavities in the gallbladder wall appear, forming diverticula by Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses dilation. These intramural diverticula become the location of biliary obstruction which afterwards becomes infected, allowing the apparition of pigment calculi in the vesicular wall, and also in the vesicular lumen. Adenomyomatosis (AMM) is also called intramural diverticulosis (IMD). Due to cysts’ superinfection, an inflammatory parietal reaction appears which leads to an important proliferation of the glandular structures and to a process of wall fibrosis, with the initial proliferation of muscular structures, then followed by its replacement through fibrosis. In time, the gallbladder turns into a “honeycomb”, losing its contractile capacity, and it can evolve to “porcelain gallbladder” or to carcinomatous transformation. Calcification appears with a 0.06-0.8% frequency rate, and carcinoma grafts on 5% of adenomyomatoses, according to data published by Sthephan Berg who examined 25,000 gallbladder specimens(2).

Adenomyomatosis frequently evolves with the formation of calculus in intramural diverticula, leading to lithiasic intramural micro-abscesses. Most of the times, AMM don’t have a clinical expression, being asymptomatic, except for cases associated to lithiasis which have symptoms specific to those of vesicular lithiasis. Often, AMM are incidental findings, after ultrasonographic (US) explorations. Ultrasound remains the gold standard technique for the diagnosis of AMM. The lesions can have three topographic localizations: fundic, segmental and diffuse. The most frequently encountered is fundic diverticulosis. Imagistically, adenomyomatosis presents as intraparietal anechogenic spaces located in a thickened vesicular wall. Sometimes, echogenic areas appear, determined by intracystic calculi or images in “comet tail”. Other times, the images can suggest a “pearl necklace” or “shinning” images(4-9). Apparently, adenomyomatosis frequency is increasing. The “incidental” echographic findings led to an increase of AMM incidence. Ultrasonography remains the method of choice for establishing the diagnosis, with a 91-95% accuracy(5,9). The thickening of the vesicular wall, localized or diffuse, remains one of the most important imagistic signs. When US is not conclusive, we resort to contrast ultrasonography, using high-frequency sondes and focal depth adjustment. The detection of Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses is obtained mostly with harmonic imaging.

Materials and method

We had access to the 42-year experience of the Caritas Surgery Clinic from Bucharest and of the First Clinic of the “Prof. Dr. Alexandru Trestioreanu” Institute of Oncology, Bucharest. The studied batch comprised 532 cholecystoses operated in the period 1977-2016, in these two surgical departments. In the analyzed batch there were registered 475 vesicular cholesteroloses and 47 adenomyomatoses. In 30 AMM cases (63.8%), vesicular lithiasis was also associated, and in seven cases (14.8%) migrated choledochal lithiasis coexisted. We must mention the fact that five cases evolved with acute symptomatology, being operated in emergency (10.6%) for acute cholecystitis. Most of our AMM patients were symptomatic, with painful postprandial pain and, sometimes, biliary colics with acute paroxysmal pain. Between 1974 and 1990, the diagnosis was established using cholecysto-cholangiography. The specific images of this exploration were suggestive when aspects of bilocular gallbladder were obtained, like “dumbbell”, “phrygian cap”, deformities, septum and diverticuli, “honeycomb” etc. Currently, the radiologic investigation was successfully replaced by ultrasonography. All those 47 AMM patients were operated on with cholecystectomy. In 32 cases, open surgery was used, and 15 patients were approached laparoscopically. Choledochian lithiasis (seven patients) benefitted from endoscopic desobstruction of the main biliary duct associated to cholecystectomy. We didn’t register postoperative complications specific to cholecystectomy. The cholecystectomy samples were histologically examined. We didn’t encounter carcinomatous transformation. The diffuse forms were found in five cases (10.6%), the fundic ones were found in 10 cases (21.27%), and the segmental ones were registered in 32 cases (68%).

We illustrate through some macroscopic and microscopic images (Prof. Dr. Eugen Brătucu Collection).

Figure 1 macroscopically depicts an adenomyomatosis. We remark an adenomyomatosic infundibular diaphragm and a fundic intramural diverticulitis.

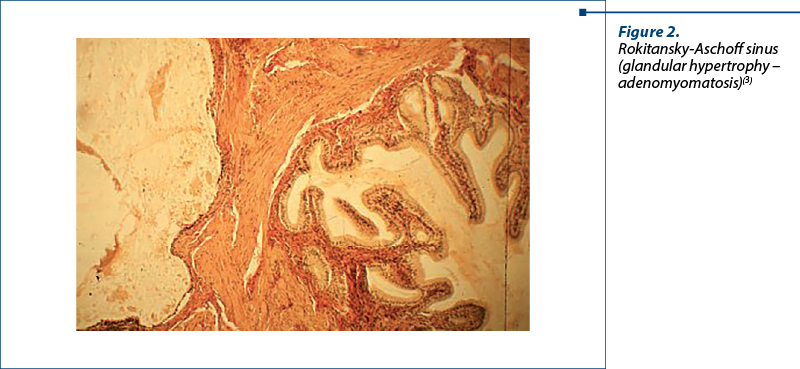

Figure 2 presents the typical adenomyomatosis histology, depicting a Rokitansky-Aschoff sinus excessively developed in the vesicular wall in the muscular layer. We can observe proliferation and glandular hypertrophy(3).

Figure 3. Gallbladder cholesterolosis is characterized by the presence of cholesterol ester deposits at the level of gallbladder mucosa. The mucosa is hyperemic and presents many yellow granulations which represent accumulations of histiocytes loaded with cholesterol and lipids at the level of chorion and submucosa.

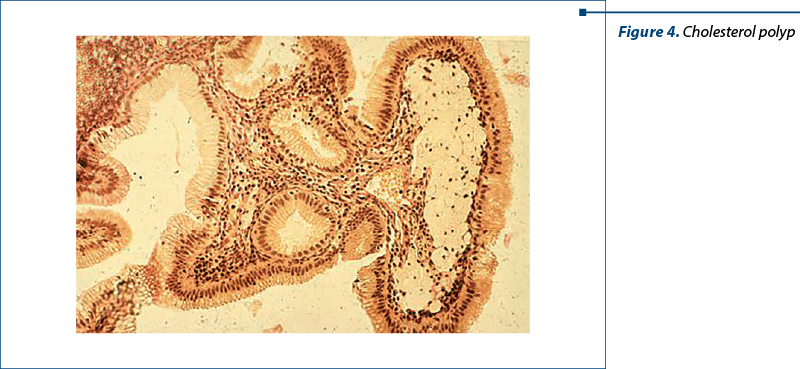

Figure 4. Typical image of a cholesterol polyp with crystals deposited in histiocytes and presented in the submucosal layer.

Discussion

The opportunity of cholecystectomy in the treatment of AMM is still under debate. Some authors recommend the laparoscopic approach only for symptomatic adenomyomatosis(6,8). Is this approach correct – laparoscopic approach only for those forms with clinical manifestation? Still, AMM is a dysplasia, an abnormal modification of tissular structure from the vesicular wall which is defined as a pathologic process of the gallbladder. In human pathology, dysplasias are frequently met, leading to sufferance and risks for different complications. Cervical dysplasia, intestinal metaplasia of the esophagus and gastric antrum, breast dysplasia, colorectal adenomatous dysplasia etc. are well known. All these have precise treatment indications, according to well-established protocols in which surgery has its place. Should AMM vesicular dysplasia fall within surgical abstention? There are some risks that appear in the evolution of an adenomyomatosis: cysts infection with micro-abscesses in the vesicular wall, the onset of intramural and intracavitary lithiasis, acute cholecystitis, calculi migration in the main biliary duct, including the possibility of neoplastic degeneration. All these can be avoided by accepting the laparoscopic approach as a therapeutic solution before the onset of the aforementioned complications. In fact, an organ with altered functions is removed, being a source of septic complications. Meanwhile, some authors are worried about the risks of developing carcinoma in the context of adenomyomatosis(9-12). Regarding the correlation between vesicular lithiasis and carcinoma, the specialty literature reveals that 95% of the carcinomas occur on lithiasic vesicles. At the same time, more than 60% of adenomyomatoses are associated to lithiasis(13,14). Older patients, above 60 years of age, with AMM, develop vesicular carcinoma with an incidence of 15.6%(12). It is obvious that vesicular dysplasias create the favorable conditions for the apparition of calculi, with all the consequences and complications derived from this association. Can we recommend surgical abstention in case of an AMM lesion with a high probability of unfavorable evolution to complications? Should we wait for the development of lithiasis, vesicular supurations, malignant transformation, evolution to “porcelain gallbladder” etc.? If this is the evolutive course of AMM, then isn’t it logical to therapeutically address the lesion in its initial, uncomplicated stages? All visceral dysplasias have precise therapeutic indications. Adenomyomatosis must benefit from a therapeutic approach similar to that of dysplasias, before the onset of complications.

Conclusions

More than 50 years have passed from the first large studies on cholecystoses and their adenomyomatosic variant(15). In those years, AMM had surgery as first-intention therapy, even though they didn’t express through clinical sufferance. Nowadays, in the age of laparoscopy, the surgical act implies a minimally invasive approach, with a reduced hospitalization and a fast favorable postoperative evolution. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be a safe and simple method of avoiding AMM complications.

Thus:

-

Cholecystoses represent a pathology of interest within the vesicular pathology (8%).

-

Complications are similar to those encountered in vesicular lithiasis.

-

The metaplastic transformation of the vesicular wall encountered in the final phases of adenomyomatosis leads to the dysfunction of the vesicular reservoir, with the possibility of lithiasis association.

-

Cholesteroloses remain responsible for fearsome complications – cholecystitis and acute pancreatitis, episodes of acute or chronic choledochian syndrome, angiocolitis and jaundice.

-

For all these reasons, including the possibility of neoplastic degeneration, cholecystoses/adenomyomatoses must remain with the absolute indication of cholecystectomy.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

King ESJ, MacCallum P. Cholecystitis glandularis proliferans (cystica). Brit J Surg. Oct. 1931;19(74):310-323, https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800197410.

-

Lee TC, Liu KL, Lai IR, Wang HP. Diagnosing porcelain gallbladder. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):1171-1172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.023

-

Cariati A, Cetta F. Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses of the gallbladder are associated with black pigment gallstone formation: a scanning electron microscopy study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2003;27(4):265-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01913120309913.

-

Hammad AY, Miura JT, Turaga KK, Johnston FM, Hohenwalter MD, Gamblin TC. A literature review of radiological findings to guide the diagnosis of gallbladder adenomyomatosis. HPB (Oxford). 2016;18:129-35. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2015.09.006.

-

Bonatti M, Vezzali N, Lombardo F, et al. Gallbladder adenomyomatosis: imaging findings, tricks and pitfalls. Insights Imaging. 2017;8(2):243-253. doi: 10.1007/s13244-017-0544-7

-

Lee KF, Hung EHY, Leung HHW, Lai PBS. A narrative review of gallbladder adenomyomatosis: what we need to know. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(23):1600. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-4897

-

Golse N, Lewin M, Rode A, Sebagh M, Mabrut JY. Gallbladder adenomyomatosis: Diagnosis and management. J Visc Surg. 2017;154(5):345-353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.06.004.

-

Pang L, Wu S, Kong J. Surgical Choice for Different Types of Gallbladder Adenomyomatosis: An Initial Experience of 20 Years Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2020;30(2):151-155. doi:10.1097/SLE.0000000000000776.

-

Suzuki K, Abe K, Ohbu M. A Resected Gallbladder Carcinoma Coexisting with Adenomyomatosis Involving Varied Degrees of Intraepithelial Dysplasia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019;29(4):290-296. doi:10.1097/SLE.0000000000000617.

-

Morikawa T, Okabayashi T, Shima Y, et al. Adenomyomatosis Concomitant with Primary Gallbladder Carcinoma. Acta Med Okayama. 2017;71(2):113-118. doi:10.18926/AMO/54979.

-

Nabatame N, Shirai Y, Nishimura A, Yokoyama N, Wakai T, Hatakeyama K. High risk of gallbladder carcinoma in elderly patients with segmental adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2004;23(4):593-598.

-

Mlinarić-Vrbica S, Vrbica Z. Correlation between cholelithiasis and gallbladder carcinoma in surgical and autopsy specimens. Coll Antropol. 2009;33(2):533-537.

-

Gulwani HV, Gupta S, Kaur S. Incidental detection of carcinoma gall bladder in laparoscopic cholecystectomy specimens: a thirteen year study of 23 cases and literature review. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2015;6(1):30-35. doi: 10.1007/s13193-015-0379-y

-

Arianoff AA. Gallbladder. In: Les cholécystoses. Edit. Arscis S.A. Bruxelles, 1966.

-

Burlui D, Condiescu M, Nissim F, Constantinescu C, Brătucu E. L’ablation de la vesicule biliaire dans les cholecysteses. Acta Gastro-Enterol Belgica. 1974;37:49-57.