Muscle cramps in cancer patients – one reason to jump off the bed

Crampele musculare la pacienţii oncologici – un motiv de a sări din pat

Abstract

Muscle cramps are quite often seen in the cancer patient, which could be caused either by the cancer itself, or by the undesirable side effects of cancer therapy. It is a frequently ignored symptom, even though it could be associated with an unsuspected underlying pathologic condition. Currently, no preventive treatments for cancer-associated muscle cramp are available, and the treatment for this symptom is nonspecific, with research being done mostly on noncancer population. Therefore, more research is needed to elucidate both the pathophysiology and the therapeutic options for muscle cramps in the oncological patient.Keywords

cancer patientsmuscle crampsdrugs causing muscle crampsdrugs for muscle crampsRezumat

Crampele musculare reprezintă o simptomatologie destul de frecvent întâlnită la mulţi dintre pacienţii cu boli oncologice. Cauzalitatea acestui simptom poate fi explicată fie prin suferinţa oncologică în sine, fie prin efectele adverse ale terapiei anticancerigene. Crampele musculare la pacienţii cu cancer sunt deseori ignorate, deşi acestea ar putea fi asociate cu o condiţie patologică subiacentă. Până în prezent, nu se cunosc metode de prevenire a acestui simptom la pacienţii cu suferinţe oncologice, tratamentele fiind nespecifice, iar majoritatea cercetărilor ştiinţifice au fost realizate la pacienţi fără cancer. Analizarea mai aprofundată a crampelor musculare la pacienţii oncologici ar putea oferi răspunsuri privind fiziopatologia lor, dar şi posibile opţiuni terapeutice.Cuvinte Cheie

pacienţi oncologicicrampe muscularemedicamente cauzatoare de crampe muscularemedicamente pentru crampe musculareMuscle cramp – sometimes called charley horse – is a spasmodic, involuntary and painful contraction of a single muscle or a muscle group. It has a sudden onset and is often accompanied by a palpable and/or visible contraction of the muscle. It can happen spontaneously while at rest or during physical activity when the muscle is in an isometric contraction. Muscle cramps may cause either limb movement or limb stiffness, and are typically relieved by stretching. Cramping is frequently preceded by fasciculations and followed by residual soreness, suggestive of muscle tissue or hypoxic/metabolic damage. Generally, it lasts for only a few minutes, but could hamper one’s sleep if it happens at night(1-4).

The incidence of muscle cramps in a healthy population is variable, with one article reporting less than 5% and another article reporting about 15%. The frequency is higher amongst the elderly. The incidence of muscle cramps tends to also be higher in cancer patients or in cancer survivors, with a study indicating about 82%. According to an article published in the press, 31% of the patients treated with cisplatin had muscle cramps, and the incidence of this symptom was significantly higher in patients treated with vismodegib (between 47% and 71.2%). Patients treated with sodinegib reported muscle cramps as the most common adverse event, and several patients had to discontinue the therapy with this hedgehog pathway inhibitor due to the severity of the muscle cramps. The cramps in these patients were noticed a few months after initiating treatment and commonly affected the patients’ daily activities. Another article reported that 56% of the autologous recipients and 52% of the allogeneic recipients have experienced muscle cramps, with 44% of them having very painful cramps. There is a consensus that prospective studies evaluating muscle cramps in patients with cancer are lacking(3-9).

It was speculated that the site of origin for muscle cramps could be at the level of the lower motor neuron, based on the observation that cramps are more frequently associated with neuromuscular diseases involving the lower motor neuron. They can be without any apparent cause when they are considered “benign” or secondary to a variety of disorders. Based on their etiology, muscle cramps could be classified into four categories:

a) cramps at rest that tend to occur at nighttime;

b) cramps associated with physical activity;

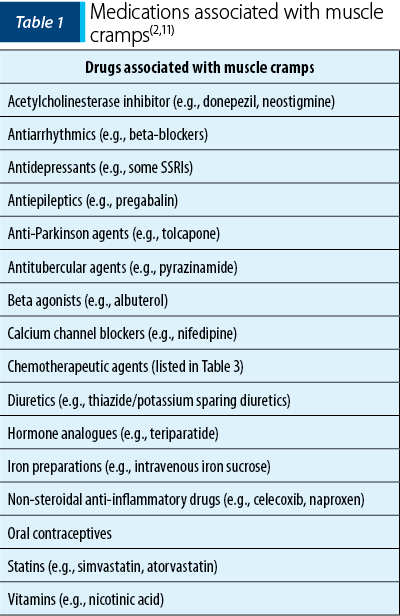

c) drug-induced cramps, and the drugs most associated with muscle cramps are listed in Table 1;

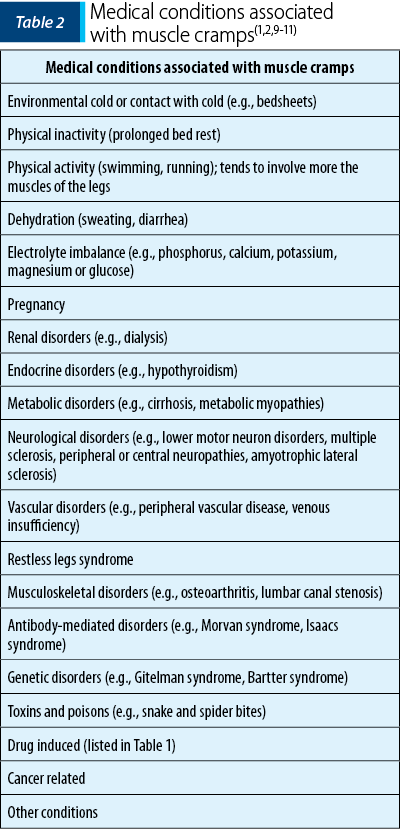

d) disease-related cramps, and a summary of the most common conditions associated with muscle cramps can be found in Table 2(1,4).

Patients with cancer may experience muscle cramps more frequently, and several hypotheses have been formulated to explain the presence of this symptom in oncological patients, such as:

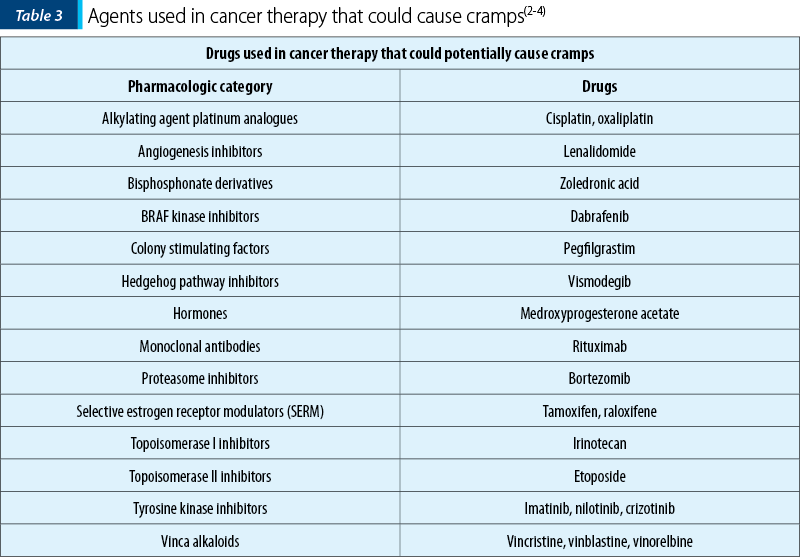

1. Side effects from the chemotherapeutic agents, with some of these agents being outlined in Table 3. The toxic effect of these agents could cause peripheral neuropathy or myopathy, lower nitric oxide levels and blood flow in muscle tissue, or affect the activation of the calcium channels in the cell membrane. There were articles suggesting that vismodegib-related muscle cramps subside after interrupting treatment in about a month and they may reoccur a few months after reinitiating vismodegib.

2. Tumor growth in or around the affected muscles or nerves.

3. Complications from radiation therapy, such as a radiation-induced plexopathy or when radiation was delivered to the lower regions of the body.

4. Complications from metastatic disease, such as epidural/brachial/lumbosacral plexus compression by tumor or leptomeningeal disease.

5. Complications from graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The classical targets of the acute GVHD are the skin, intestinal tract and liver, whereas chronic GVHD may involve additional organs like fascia, joints, eyes and the lungs. As expected, the muscle cramps are more frequently encountered in chronic GVHD where the toxicity of long-term immunosuppressants versus prolonged use of steroids along with a neuropathy or a myopathy are considered additional risk factors for cramps.

6. Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with muscle cramps, such as polymyositis, Guillain-Barré syndrome or neuromyotonia, known as the Isaacs syndrome.

7. Metabolic, endocrine or electrolytes abnormalities, commonly seen in cancer patients(1,4-7,10,12-16).

While trying to elucidate possible etiologies for muscle cramps in the cancer patient, a clinician should perform a thorough neurological exam and could order tests such as:

-

Comprehensive metabolic panel.

-

Complete blood count.

-

Electrolyte panel.

-

Thyroid function tests (TFTs).

-

Liver function tests (LFTs).

-

Vitamin B12 and folate levels.

-

Serum creatinine kinase (CK).

-

Nerve conduction studies.

-

Complete battery of antibodies. Several articles mentioned antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies along with antibodies directed against potassium channels, leucine-rich, glioma inactivated 1 protein, contactin-associated protein-2 or peripheral nerve myelin.

-

Cerebrospinal fluid examination.

-

Ultrasonography.

-

Angiography.

-

Skin biopsy(4,9,11,12).

The treatment of cramps in the cancer patient is nonspecific and employs both nonpharmacological and pharmacological approaches. The consensus in literature is that no interventions to prevent cramps are currently available(4,9).

Several studies and the American Cancer Society recommend the following nonpharmacological techniques to prevent or address the muscle cramps:

1. Proper hydration that may correct dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, even though there is little information investigating its use and efficacy.

2. Correction of electrolytes abnormalities; in particular, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia. A potassium-rich diet with bananas, raisins, yogurt, peaches and spinach could be suggested if the patient is found with hypokalemia. The patient could be recommended dairy products (milk, yogurt, cheese), salmon, figs, soybeans, dark green and leafy vegetables or fortified juices and cereals if calcium level is found below normal limits. Dietary products like avocados, dark chocolate, beans, peas, whole grains, bananas or fatty fish like salmon, mackerel and halibut could be proposed if the patient has hypomagnesemia.

3. Sipping pickle juice during a limb cramp could reduce the duration of the cramp, possibly related to an inhibitory oropharyngeal reflex mechanism.

4. Local and general warmth, considering that cold temperatures and shivering may bring on cramps.

5. Local massage that may be applied by the patient or caregivers if agreed upon by the oncologist.

6. Muscle stretching, especially stretching against the cramp, for as long as possible, may help by activation of antagonist muscles.

7. Creating a bed cradle to keep blankets from touching body parts for the patients confined to bed could be recommended.

8. Local electrical stimulation, that could elevate the cramp threshold, could be suggested as well(2,4,9,11,18).

Nonprescription vitamins/supplements that could be recommended for the treatment of cramps are:

1. Magnesium. Magnesium is widely marketed online for the prevention of muscle cramps and is available in pharmacies and health food stores; however, its efficacy for treatment of muscle cramps remains unclear. A Cochrane review looked at eleven trials (open‐label, single‐blind, or double‐blind randomized controlled trials) with magnesium supplement in oral or i.v. forms in 735 individuals. The conclusions of these studies are that magnesium supplementation is unlikely to provide a meaningful cramp prophylaxis for older adults with skeletal muscle cramps and that more research is needed for pregnancy‐associated rest cramps. Unfortunately, the authors could not identify any studies on patients with cramps and a cancer diagnosis. Caution needs to be employed when recommending magnesium, since the supplement could cause diarrhea.

2. Vitamin B complex. 30 mg per day of vitamin B6 reduced muscle cramps in 86% of patients in a small study with 28 patients. However, vitamin B complex is not recommended by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) for the treatment of muscle cramps in patients with cancer.

3. Vitamin E. There are three studies showing that vitamin E reduced muscle cramps(3,9,11,18).

Various prescription medications were studied for the treatment of cramps, even though the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), in its guidelines for the prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, does not recommend any medications for the prevention or treatment of muscle cramps in cancer patients. Some of these medications are:

1. Quinine. Quinine’s benefits in preventing/reducing muscle cramps were proven by several studies. A few studies on noncancer patients have concluded that quinine moderately improved muscle cramps. A study has shown that quinine reduced cramps number by 28%, cramps intensity by 10%, and the number of cramps days by 20%, but without affecting the duration of the cramps. A small study found that 14 out of 15 patients treated with quinine for vismodegib-induced cramps had a positive response; equivalent results were seen in another study on seven patients with a similar condition. The daily dose of quinine used for the prevention of muscle cramps is 200-300 mg, and a few single trials proved that quinine in combination with theophylline were more efficacious in relieving cramps that quinine alone. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in UK suggested the short-term use of quinine by the patients whose quality of life and sleep are affected by cramps. Unfortunately, quinine was associated with a plethora of side effects, some of them significant enough for the American Academy of Neurology to recommend against the routine treatment of cramps with quinine and for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to withdraw quinine from over‐the‐counter use, and for all indications other than uncomplicated falciparum malaria. The most common serious side effects, which may occur with a frequency of 2-4%, were quinine‐induced thrombocytopenia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation and bleeding diathesis. Other side effects worth mentioning are cinchonism with the chronic use of quinine (nausea, vomiting, vertigo, visual disturbances, tinnitus and hearing impairment), cardiac arrhythmias, acute intoxication (after ingestion of 4 to 12 g of quinine) and death from respiratory arrest. Therefore, the use of quinine should be restricted to serious cases of cramps and under strict monitorization for side effects.

2. Phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme inhibitors (like sildenafil) or xanthine derivatives (like pentoxifylline) may be useful for muscle cramps by increasing the local levels of nitric oxide and, subsequently, causing vasorelaxation and myorelaxation.

3. Muscle relaxants (e.g., cyclobenzaprine, carisoprodol, baclofen, orphenadrine). There was a study showing that orphenadrine citrate, in a dose of 100 mg twice a day for a month, significantly lowered the muscle cramps frequency and duration, as well as the intensity of the pain (p<0.001).

4. Sodium channel blocker agents (e.g., phenytoin, carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine) were shown to be helpful in the cramp-fasciculation syndrome in various case reports, and an article mentioned phenytoin and carbamazepine as being useful for frequent daytime cramps. Mexiletine is another sodium channel blocker used as a class 1B antiarrhythmic which in doses of 150 mg twice a day can be utilized for cramps in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

5. Calcium channel blockers (diltiazem, amlodipine). 30 mg of diltiazem hydrochloride given to thirteen patients having at least two cramps per week lead to a reduction (-5.84 to -0.16 cramps per two-week treatment phase; p=0.04) in the number of cramps compared to placebo in a double-blind, cross-over study, making ESMO in its guidelines for orphan symptoms to state that “the use of diltiazem hydrochloride in reducing the number of cramps may exert some efficacy”. Another study, with 10 mg per day of amlodipine besilate administered to nine patients experiencing vismodegib-induced muscle cramps, revealed the reduction of the frequency of cramps during a period of eight weeks by 5.81% per week (95% CI; -10.15% to -1.48%; p=0.009), with ESMO stating in the same guidelines that “amlodipine may be effective in vismodegib-induced muscle cramps”.

6. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) analogues (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin). No difference between the treatment group and placebo was found in a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of gabapentin at a dose of 3600 mg a day in 204 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and, therefore ESMO does not recommend this approach for muscle cramps for the oncological patient.

7. Naftidrofuryl oxalate is a vasodilator acting on the 5-HT2 serotonergic receptors that reduces the frequency of cramp episodes and increases the frequency of cramp-free days, likely by improving cellular oxidative metabolism. This medication, which is not available in the USA, was proven to significantly reduce the frequency of rest cramps in a randomized control trial involving 14 participants. Several studies have shown that oral naftidrofuryl was beneficial in improving walking distance for patients with intermittent claudication. ESMO cited studies proving that naftidrofuryl 300 mg, two times per day, has led to a significant reduction of cramps and to an increase in cramps-free days(2-4,7,9,11,14,18-24).

In its guidelines for orphan symptoms, ESMO made the following recommendations for muscle cramps in cancer patients:

-

Amlodipine besilate, 10 mg per day, for vismodegib-induced cramps.

-

Naftidrofuryl, 300 mg twice a day.

-

Quinine, 200-300 mg per day(3).

In conclusion, muscle cramps in cancer patients should not be considered a benign condition without a proper investigation, and further research is needed to uncover treatment options for this condition frequently encountered by patients during their cancer journey.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY licence.

Bibliografie

-

Kraus PD, Wolff D, Grauer O, Angstwurm K, Jarius S, Wandinger KP, Holler E, Schulte-Mattler W, Kleiter I. Muscle cramps and neuropathies in patients with allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and graft-versus-host disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44922.

-

Swash M, Czesnik D, de Carvalho M. Muscular cramp: causes and management. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(2):214-221.

-

Santini D, Armento G, Giusti R, Ferrara M, Moro C, Fulfaro F, Bossi P, Arena F, Ripamonti CI; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of orphan symptoms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. ESMO Open. 2020;5(6):e000933.

-

Siegal T. Muscle cramps in the cancer patient: causes and treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991;6(2):84-91.

-

Steiner I, Siegal T. Muscle cramps in cancer patients. Cancer. 1989;63(3):574-7.

-

Siegal T, Haim N. Cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Frequent off-therapy deterioration, demyelinating syndromes, and muscle cramps. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1117-23.

-

Fife K, Herd R, Lalondrelle S, Plummer R, Strong A, Jones S, Lear JT. Managing adverse events associated with vismodegib in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2017;13(2):175-184.

-

Villani A, Fabbrocini G, Scalvenzi M. Sonidegib-induced muscle spasms in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma: Strategies to adopt. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(7):e15531.

-

Lehky T, Fernandez IP, Krakow EF, Connelly-Smith L, Salit RB, Vo P, Oshima MU, Onstad L, Carpenter PA, Flowers ME, Lee SJ. Neuropathy and Muscle Cramps in Autologous and Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Survivors. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(9):608.e1-608.e9.

-

Krexner E, Stickler A, Prainer C, Finsterer J. Acute, generalised but transient muscle cramping and weakness shortly after first oxaliplatin infusion. Med Oncol. 2012;29(5):3592-3.

-

Allen RE, Kirby KA. Nocturnal leg cramps. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(4):350-5.

-

Lopate G, Streif E, Harms M, Weihl C, Pestronk A. Cramps and small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48(2):252-5.

-

Bradley WG, Lassman LP, Pearce GW, Walton JN. The neuromyopathy of vincristine in man. Clinical, electrophysiological and pathological studies. J Neurol Sci. 1970;10(2):107-31.

-

Karatas F, Sahin S, Babacan T, Akin S, Sever AR, Altundag K. Leg cramps associated with tamoxifen use – possible mechanism and treatment recommendations. J BUON. 2016;21(2):520.

-

Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, Dirix L, Lewis KD, Hainsworth JD, Solomon JA, Yoo S, Arron ST, Friedlander PA, Marmur E, Rudin CM, Chang AL, Low JA, Mackey HM, Yauch RL, Graham RA, Reddy JC, Hauschild A. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2171-9.

-

https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side-effects/pain/leg-cramps.html

-

Hawke F, Sadler SG, Katzberg HD, Pourkazemi F, Chuter V, Burns J. Non-drug therapies for the secondary prevention of lower limb muscle cramps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5(5):CD008496.

-

Garrison SR, Korownyk CS, Kolber MR, Allan GM, Musini VM, Sekhon RK, Dugré N. Magnesium for skeletal muscle cramps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;9(9):CD009402.

-

Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, Lavoie Smith EM, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, Chauhan C, Gavin P, Lavino A, Lustberg MB, Paice J, Schneider B, Smith ML, Smith T, Terstriep S, Wagner-Johnston N, Bak K, Loprinzi CL; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941-67.

-

El-Tawil S, Al Musa T, Valli H, Lunn MP, Brassington R, El-Tawil T, Weber M. Quinine for muscle cramps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD005044.

-

Abd-Elsalam S, El-Kalla F, Ali LA, Mosaad S, Alkhalawany W, Elemary B, Badawi R, Elzeftawy A, Hanafy A, Elfert A. Pilot study of orphenadrine as a novel treatment for muscle cramps in patients with liver cirrhosis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(3):422-427.

-

de Backer TL, Vander Stichele R, Lehert P, Van Bortel L. Naftidrofuryl for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12(12):CD001368.

-

Young JB, Connolly MJ. Naftidrofuryl treatment for rest cramp. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69(814):624-6.

-

Cohen SP, Mullings R, Abdi S. The pharmacologic treatment of muscle pain. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(2):495-526.