CARES – un instrument pentru sfârsitul vieţii

CARES – a tool for the dying

Abstract

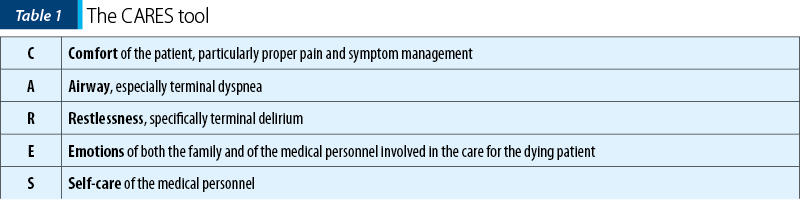

Bonnie Freeman (RN, DNP, ANP, CT, ACHPN) was a pain and palliative care medicine nurse practitioner in the Department of Supportive Care Medicine at the City of Hope National Medical Center, who developed the CARES tool as part of her doctoral program requirement at the Azusa Pacific University. The CARES tool is a reference guide that focuses on symptom management in end-of-life care, such as Comfort, Airway, Restlessness and delirium, Emotional and spiritual support, and Self-Care. It was initially presented as a poster in 2012, receiving 98% approval rating by palliative care experts. Since its inception, hundreds of formal requests to utilize the CARES tool for education and training in the United States of America as well as in other countries were granted. Many medical institutions do not have set guidelines specific to comfort care; the CARES tool acronym format focuses on the unique needs of this patient population by optimizing the quality of life. This article describes the need for healthcare provider education in addressing symptom management in the early stages of end-of-life care, in order to relieve suffering and maintain patient’s dignity. The article details each component of the CARES tool, as well as recommended guidelines.Keywords

end of lifecomfortdyspneadeliriumemotionsself-carepainsymptom managementRezumat

Bonnie Freeman (RN, DNP, ANP, CT, ACHPN) a fost o asistentă medicală de îngrijire paliativă în cadrul Departamentului de medicină paliativă al Centrului Medical Naţional City of Hope, care a dezvoltat instrumentul CARES ca parte a cerinţei programului ei de doctorat la Universitatea Azusa Pacific. CARES este un ghid de referinţă care se concentrează pe controlul simptomelor în îngrijirea de la sfârşitul vieţii, cum ar fi confortul, căile respiratorii, neliniştea sau delirul, sprijinul emoţional şi spiritual şi îngrijirea de sine. CARES a fost prezentat iniţial ca un poster în 2012 şi a primit aprobarea a 98% dintre experţii în îngrijire paliativă. Încă de la început au fost o multitudine de solicitări de utilizare a CARES pentru educaţie şi formare profesională în Statele Unite ale Americii, precum şi în alte ţări. Multe instituţii medicale nu au ghiduri specifice îngrijirii de confort la sfârsitul vieţii, iar instrumentul CARES se concentrează pe nevoile unice ale acestei categorii de pacienţi care necesită optimizarea calităţii vieţii. Acest articol detaliază fiecare componentă a CARES şi descrie necesitatea educaţiei personalului medical în gestionarea simptomelor din stadiile incipiente ale îngrijirii de la sfârşitul vieţii, pentru a ameliora suferinţa şi pentru a păstra demnitatea pacientului.Cuvinte Cheie

sfârşitul vieţiiconfortdispneedeliremoţiiîngrijire de sinedureremanagementul simptomelorThe United States of America healthcare expenditure in 2014 represented 17.5% of the total gross domestic product (GDP) and with only five percent of the population accounted for over half of the healthcare spending. A significant proportion of this populational group was represented by patients of old age or with multiple chronic conditions, including patients approaching end of life(1).

A prospective cohort study looked at all adult cancer deaths in the state of Connecticut in 1994 and noticed that only 29% of the patients died at home compared to 42% who died in a hospital, 17% who expired in a nursing home, and another 11% who passed away in an inpatient hospice facility. Factors like white race, being married, being female, residing in a higher income area, having a longer survival after the cancer diagnosis, along with a greater availability to hospice care were associated with dying at home. However, the same study pointed at the fact that 70% of these patients died in various institutions where they were assisted on their last road by healthcare providers, physicians or nurses(2).

Considering these data, several studies have drawn attention to the need for education about end of life for the healthcare providers to ensure a “good death” and with less suffering for patients and their families. One study even stated that the lack of education in end of life precludes a “good death” for many patients with a life-threatening illness in modern hospitals(3,4).

A “good death” was perceived as a departure from life while having an adequate pain and symptom management, awareness of death, preservation of the patient’s dignity, presence and support of the family, along with communication between the patient, the family and all healthcare providers(5).

The CARES tool emerged after realizing the significant existent gaps and subsequent need for education about end of life. Its content was initially validated as a poster presentation in 2012, with a positive approval rating of 98% by 125 experts in palliative care attending the 19th International Congress on Palliative Care in Montreal, Canada. They were asked the following questions:

a)

Could the use of the CARES tool assist in the education of healthcare staff?

b)

Could the CARES tool be integrated into standards of care?

c)

Does the CARES tool effectively prompt the obtaining of orders and supportive measures for the dying patient and the family?(6).

Since then, hundreds of formal requests have been granted to utilize the CARES tool for end-of-life training and education in the United States and other countries.

The CARES tool is summarized in the Table 1(6).

Comfort (pain control)

Comfort is of utmost importance for patients approaching end of life, as demonstrated in a study by Singer et al. in which researchers had face-to-face interviews with 126 patients about their views on end-of-life issues. These patients identified five domains of quality end-of-life care:

Adequate pain and symptom management

Avoiding inappropriate prolongation of dying

Achieving a sense of control

Relieving burden

Strengthening relationships with their loved ones(7).

According to World Health Organization (WHO), controlling symptoms at end of life at an early stage to relieve suffering and to respect a person’s dignity is an ethical duty of every medical personnel. The same organization mentioned that approximately 80% of the patients with AIDS or cancer and 67% of the patients with cardiovascular disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could experience moderate to severe pain at the end of life. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) mentions that about 30-75% of patients with cancer do report pain in the last days of life. Both organizations agree that opioids are essential for managing pain in cancer patients in general and in patients at the end of life in particular, to avoid unnecessary suffering from physical pain(8,9).

The opioids may be required around-the-clock and at doses expected to match the level of suffering; as a result, there should not be a maximum dose of opioids at the end of life. Literature recommends that palliative care specialists should be involved if clinicians fear that the opioids may risk shortening the patient’s life or if the dose escalations are greater than 100% per day(6,10).

Palliative care specialists could invoke the doctrine of “double effect” if concerns are raised that the opioids may hasten the patient’s death. This doctrine originated from Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century and stipulates that “an action in the pursuit of a good outcome is acceptable, even though it is achieved through means with an unintended but foreseeable negative outcome” when “the negative outcome is outweighed by the good outcome”. At the end of life, relief from suffering should be considered the good outcome whereas a potential shortening of life represents the negative outcome(10,11).

The administration route for opioids and for medication in general should be either intravenous or subcutaneous in an intermittent or continuous fashion. Forceful oral administration of medication in a patient who lost the ability to swallow, or placement of a gastrostomy or nasogastric tube should be avoided since all these measures could needlessly increase the patient’s discomfort and risks for vomiting and aspiration. Using transdermal route should also be discouraged for these patients since absorption could be affected by decreased peripheral perfusion or fever(9).

There are no strict recommendations regarding the class of opioids that is to be used at the end of life; however, an opioid rotation may be needed if the patient develops a pain crisis or renal failure. In the latter situation, fentanyl or methadone, which have inactive metabolites and minimal renal excretion, should be preferred over morphine because its metabolites (morphine 3 and 6 glucuronide) are renally excreted and could lead to unwanted manifestations of opioid-induced neurotoxicity due to accumulation(6,9).

Airway (terminal dyspnea)

Dyspnea, perceived as a subjective experience of uncomfortable breathlessness, is one of the most distressing symptoms at the end of life. It is present in about 90% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, in 70% of patients with lung cancer, and in 65% of those with heart failure(12).

Opioids are the mainstay for managing terminal dyspnea, with WHO recommending the use of morphine (oral or parenteral) based on clinical evidence that morphine is effective for the treatment of dyspnea in palliative care(12,13).

For terminal breathlessness, opioids are generally prescribed at lower doses than the ones used for pain; however, in the case of opioid-tolerant patients experiencing terminal dyspnea ESMO recommends an increase of the baseline dose of opioid by 25-50%. Benzodiazepines can be helpful if dyspnea persists and especially when associated with anxiety. Steroids that reduce the airway inflammation and edema could be utilized as well(9,12).

Supplemental oxygen should not be recommended for routine use, considering the lack of evidence that oxygen therapy relieves dyspnea, unless when the patient suffers from hypoxemia. Literature even mentioned that supplemental oxygen may actually prolong the dying process which in turn may increase suffering for patients and their families. However, oxygen use at the end of life is a standard practice in some countries where the families may feel better that “something is done”(14,15).

In the last three days of life, about 12-80% of the patients may produce loud gargling noises, also known as “death rattle”, due to the accumulation of tracheobronchial secretions. Several studies have shown that this symptom is unlikely to make the patient suffer, but it is quite disturbing for the families who may have the feeling that their loved one is drowning in his/her own secretions. To avert this problem anticholinergic agents like glycopyrrolate, hyoscyamine, atropine or scopolamine could be employed. Suctioning should be advised against, since it does not provide a long-term solution and is often uncomfortable for patients(6,9).

Restlessness (terminal delirium)

Terminal delirium can be encountered in 25% to 85% of the dying patients, who may experience restlessness, agitation, confusion, nightmares and hallucinations. Unfortunately, delirium tends to be overlooked, with a study revealing that only 30% of the cases in an inpatient hospice were properly identified and treated(6,16).

Clinicians need to first assess for reversible causes of the delirium, such as side effects from medications or uncontrolled symptoms, particularly uncontrolled pain or fecal impaction or urinary retention, prior to initiating the medical treatment. A useful mnemonic formula looking into potential etiologies of delirium is “I WATCH DEATH” (Infections, Withdrawal, Acute metabolic causes, Trauma, CNS pathology/Constipation, Hypoxia, Deficiencies, Endocrinopathies, Acute vascular problems, Toxins, Heavy metals)(16,17).

Antipsychotics, at lower doses than the ones used for a psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia, are the drugs of choice in relieving delirium. Benzodiazepines could be employed as well in the management of delirium, especially when anxiety and restlessness are present, but cautiousness is recommended, knowing that the same drugs could cause paradoxical agitation(6,17).

For refractory symptoms with no effective treatment and causing suffering at the end of life, clinicians need to consider palliative sedation (not addressed in this article). A symptom such as pain, dyspnea, delirium, terminal hemorrhage etc. could be considered refractory if the available treatment either does not work, or the effects take too long to happen, or the side effects are not acceptable for the patient(18).

Emotions (family’s and medical personnel’s)

Literature defines a family caregiver as any family member, friend or partner, who has a significant relationship with the patient and cares for him/her. An article mentioned that the caregiver distress rises steadily in the patient’s last months of life, from 15% at six months before death to 28% in the final week of life, mostly because of the caregiver level of involvement in caring for the patient and his/her affective proximity to the patient. Anxiety was reported in 15% and loneliness in about 10% of the caregivers interviewed(19,20).

Some of the risk factors that could potentially increase the caregivers’ distress may be:

1.

Impact on the caregiver’s personal life by the patient’s decline and death (e.g., sleep deprivation, time off work).

2.

Lack of understanding of the natural process of dying.

3.

Uncertainty regarding the patient’s last wishes, like for example when there are no advance directive on file or when the patient refuses to engage in discussions about end of life, with literature showing that younger patients are more resistant to talk about end of life.

4.

Presence of anticipatory grief defined as the fear of losing the significant other.

5.

Difficulties in dealing with the unpredictability of the course of the illness.

6.

Difficulties in accepting the patient’s progressive decline with loss of autonomy and dignity.

7.

Feelings of hopelessness due to lack of any control over the patient’s decline.

8.

Anticipation of death with irreversible separation.

9.

Relational loss that may be described as loss of dialogue and presence or loss of protection.

10.

Patient’s frustration with his/her condition perceived as degrading that could even lead to refusal to accept care(19,21).

Each caregiver or family has unique ways of expressing distress that may vary from extreme quietness to extreme loudness, based on their feelings and personality.

The medical team needs to be around the caregivers and the patients at the end of life and provide emotional, spiritual, psychosocial and cultural support. Communication at the end of life is crucial to ensure healthy grieving for the family and a “good death” for the declining patient. Caregivers need to be educated on the natural progression of the disease and on the signs and symptoms of dying and understand that it is the terminal disease that is causing the patient’s demise and not dehydration or starvation or medications such as the opioids or benzodiazepines. Medical team should involve the caregivers for as much as possible in caring for their loved one. The team should also understand the caregivers’ mood instability, impatience or irritability because they are the ones losing someone very dear to them. Bonnie not once has told us: “Remember, it is not what you do, but how you made them feel that will be remembered”(6,19).

The members of the medical team need to also cope with their own emotions while caring for patients in their last days or hours and while facing someone else’s death. These emotions could be triggered by memories from their past when they too lost someone they loved or by feelings and fears about their own mortality or by the caregivers’ reactions to loss.

Self-care

The final topic addressed in the CARES tool is the importance of self-care for the healthcare providers. As discussed earlier, caring for the dying and their family can be very stressful. Issues relating to moral distress, burnout and compassion fatigue need to be anticipated and addressed before they become overwhelming. The need to communicate and seek out personal and professional meaning is essential. Education, professional grieving and reframing the sense of failure are examples of suggested methods to reduce stress and unrealistic expectations. Examples of self-care activities could include taking vacations, enjoying hobbies or participating in activities that can relax and recharge the healthcare provider(6).

A satisfaction of knowing that one made a difference in the lives of a dying patient’s family is often very rewarding and sustains many healthcare providers in their long careers of caring for the dying(6).

It was noted that many medical institutions had no set guidelines in managing symptoms during end of life, resulting in a gap in care for patients with life-limiting illness. Oftentimes, delayed interventions contributed to unnecessary suffering for the patients and their families. The CARES tool was created to provide a systematic approach in addressing the most common symptoms of terminally ill patients to ensure that their needs are met and their dignity is intact.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information, including the CARES booklet, can be found on City of Hope training site: http://www.supportivecaretraining.com. For permission to use the CARES material, please contact: carestool@coh.org.

Bibliografie

-

Mitchell EM, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Statistical Brief #497: Concentration of Health Expenditures in the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population, 2014. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st497/stat497.pdf

-

Gallo WT, Baker MJ, Bradley EH. Factors associated with home versus institutional death among cancer patients in Connecticut. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Jun;49(6):771-7. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49154.x.

-

Oliver T, O’Connor SJ. Perceptions of a “good death” in acute hospitals. Nurs Times. 2015 May 20-26;111(21):24-7. PMID: 26492700.

-

Kring DL. An exploration of the good death. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2006 Jul-Sep;29(3):E12-24. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200607000-00011.

-

Granda-Cameron C, Houldin A. Concept analysis of good death in terminally ill patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012 Dec;29(8):632-9. doi: 10.1177/1049909111434976.

-

Freeman, Bonnie RN, MSN, ANP CARES. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. May 2013 May;15(3):147-153. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e318287c782.

-

Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999 Jan 13;281(2):163-8. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163.

-

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

-

Crawford GB, Dzierżanowski T, Hauser K, Larkin P, Luque-Blanco AI, Murphy I, Puchalski CM, Ripamonti CI; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Care of the adult cancer patient at the end-of-life: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open. 2021 Aug;6(4):100225. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100225.

-

Sykes N, Thorns A. The use of opioids and sedatives at the end-of-life. Lancet Oncol. 2003 May;4(5):312-8. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01079-9.

-

Olsen ML, Swetz KM, Mueller PS. Ethical decision making with end-of-life care: palliative sedation and withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010 Oct;85(10):949-54. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0201.

-

Kreher M. Symptom Control at the End-of-life. Med Clin North Am. 2016 Sep;100(5):1111-22. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.04.020.

-

https://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/19/applications/PalliativeCare_8_A_R.pdf

-

Kloke M, Cherny N; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Treatment of dyspnoea in advanced cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2015 Sep;26 Suppl 5:v169-73. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv306.

-

Quinn-Lee L, Gianlupi A, Weggel J, Moch S, Mabin J, Davey S, Davis L, Williams K. Use of oxygen at the end-of-life: on what basis are decisions made? Int J Palliat Nurs. 2012 Aug;18(8):369-70, 372. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2012.18.8.369.

-

Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, Nanni MG, Berardi MA, Caruso R, Riba M. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015 Mar;17(3):550. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0550-8.

-

Albert RH. End-of-Life Care: Managing Common Symptoms. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Mar 15;95(6):356-361.

-

Payne SA, Hasselaar J. European Palliative Sedation Project. J Palliat Med. 2020 Feb;23(2):154-155. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0606.

-

Coelho A, de Brito M, Teixeira P, Frade P, Barros L, Barbosa A. Family Caregivers’ Anticipatory Grief: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Its Multiple Challenges. Qual Health Res. 2020 Apr;30(5):693-703. doi: 10.1177/1049732319873330.

-

Seow H, Stevens T, Barbera LC, Burge F, McGrail K, Chan KKW, Peacock SJ, Sutradhar R, Guthrie DM. Trajectory of psychosocial symptoms among home care patients with cancer at end-of-life. Psychooncology. 2021 Jan;30(1):103-110. doi: 10.1002/pon.5559.

-

von Blanckenburg P, Leppin N, Nagelschmidt K, Seifart C, Rief W. Matters of Life and Death: An Experimental Study Investigating Psychological Interventions to Encourage the Readiness for End-of-Life Conversations. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(4):243-254. doi: 10.1159/000511199.