Real-world evidence with nivolumab in advanced non-small cell lung cancer – second line and beyond. Our experience in Romania following straightaway reimbursement of healthcare costs

Date de tip real world privind utilizarea nivolumabului în cancerul pulmonar nonmicrocelular avansat – dincolo de linia a doua. Experienţa noastră în România imediat după rambursarea imunoterapiei prin sistemul naţional de sănătate

Abstract

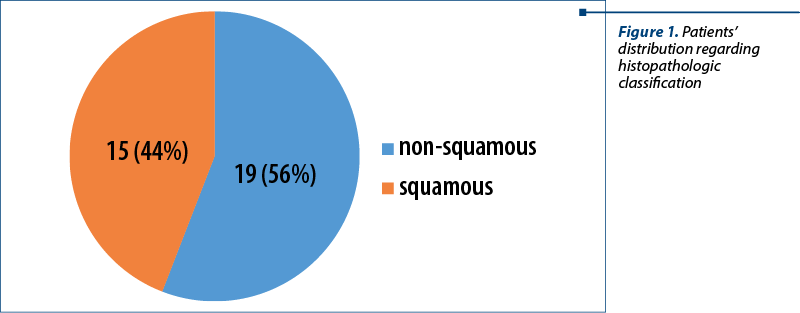

Background. Lung cancer represents the main cause of cancer-related mortality at a worldwide level and ranks second in global incidence statistics. The therapeutic management of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been substantially modified by the development of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), nivolumab, pembrolizumab, durvalumab and atezolizumab. In Romania, the reimbursement of healthcare costs for immune checkpoint inhibitors has started since late 2017. Aim of the study. The assessment of efficacy, safety profile, overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) from real-world data for nivolumab as second-line therapy for advanced and metastatic NSCLC. Our real-world study was conducted between 1.01.2018 and 31.12.2020, right after the approval of nivolumab in Europe for metastatic NSCLC. Methodology. For data analysis, we used R programming language, version 3.6.2, the Excel application in Microsoft 365 for Enterprise pack. Results. We studied 34 participants from our lot. Nivolumab was administered from second line and beyond. The average age was 65.5 years old. The majority of patients had multiple comorbidities. The histopathology was represented by 56% non-squamous NSCLC, and 44% squamous NSCLC. The overall survival for nivolumab therapy was 72.3 weeks (18.07 months). The overall survival for non-smokers was 32.5 weeks (8.12 months) versus 93 weeks for smokers (23.25 months). The overall survival for women was 15.3 weeks (3.8 months) and for men this value could not be reached. The overall survival for squamous carcinoma was 72.3 weeks (18.1 months), and for non-squamous carcinoma, it was 93 weeks (23.25 months). Median PFS was 17.3 weeks (4.3 months). Conclusions. ICI with nivolumab administered from second line and beyond had a favorable safety profile and manageable adverse events, similar to those described in pivotal studies, making them a reasonable choice in pretreated, frail and elderly patients. Distinctively, our real-world data regarding OS and PFS did not show the same advantage magnitude as seen in CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 studies.Keywords

advanced non-small cell lung cancerimmune checkpoint inhibitorimmunotherapynivolumabprogrammed death-ligand 1real-world evidenceRezumat

Context. Neoplasmul pulmonar reprezintă principala cauză a mortalităţii prin cancer la nivel mondial, ocupând locul al doilea în statisticile de incidenţă globală. Managementul terapeutic al cancerului pulmonar fără celule mici (NSCLC) a fost modificat substanţial, prin descoperirea şi dezvoltarea inhibitorilor punctelor de control imun (ICI), nivolumab, pembrolizumab, durvalumab şi atezolizumab. În România, rambursarea costurilor pentru terapiile cu inhibitori ai punctelor de control imun a început la sfârşitul anului 2017. Obiectivul studiului. Evaluarea eficacităţii, a profilului de siguranţă, a supravieţuirii globale (OS) şi a supravieţuirii fără semne de progresie (PFS) evidenţiate în datele din lumea reală (RWD) pentru nivolumab ca terapie de linia a doua în NSCLC avansat sau metastatic. Acesta a fost un studiu de tip real-world evidence, de tip cohortă, retrospectiv, întreprins într-un singur centru, între ianuarie 2018 şi decembrie 2020, imediat după aprobarea nivolumabului în Europa de Est pentru tratamentul cancerului pulmonar fără celule mici metastatic. Metodologie. Pentru analiza datelor, am folosit limbajul de programare R, versiunea 3.6.2, aplicaţia Excel în pachetul Microsoft 365 pentru Enterprise. Rezultate. Am studiat 34 de participanţi din lotul descris. Nivolumab a fost administrat de la a doua linie şi mai departe. Vârsta medie a fost de 65,5 ani. Majoritatea pacienţilor au avut comorbidităţi multiple. Distribuţia histologică a fost de 56% pentru NSCLC nonscuamos şi 44% pentru NSCLC scuamos. Supravieţuirea globală pentru terapia cu nivolumab a fost de 72,3 săptămâni (18,07 luni). Supravieţuirea globală pentru nefumători a fost de 32,5 săptămâni (8,12 luni), faţă de 93 de săptămâni pentru fumători (23,25 luni). Supravieţuirea globală pentru femei a fost de 15,3 săptămâni (3,8 luni), iar pentru bărbaţi această valoare nu a putut fi calculată. Supravieţuirea globală pentru carcinomul scuamos a fost de 72,3 săptămâni (18,1 luni), iar pentru carcinomul nonscuamos, a fost de 93 de săptămâni (23,25 luni). Mediana PFS a fost de 17,3 săptămâni (4,3 luni). Concluzii. ICI cu nivolumab administrat în şi din a doua linie a prezentat un profil de siguranţă favorabil şi evenimente adverse gestionabile, similare celor din studiile-pivot, care îl fac o alegere rezonabilă pentru pacienţii pretrataţi, fragili sau vârstnici. În mod distinct, datele noastre de tip real-world evidence pentru OS şi PFS nu arată aceeaşi amploare a avantajului descrisă în studii consacrate precum CheckMate 017 şi CheckMate 057.Cuvinte Cheie

cancer bronhopulmonar non-microcelular avansatdate de tip real worldinhibitori ai punctelor de control imunimunoterapienivolumabligandul 1 al apoptozeiIntroduction

Lung cancer represents the main cause of cancer-related mortality at a worldwide level and ranks second in the global incidence statistics(1). Lung cancer is divided into two main histologic entities: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC accounts for the majority of cases (84%), which are diagnosed at an advanced stage (65-70%). Most patients initially present with metastatic disease (stage IVA to IVB)(2).

Advanced NSCLC tumors have dismal survival rates, reaching from 19% to 7% for the five-year survival rates. These survival rates remain low, even though there has been a slight ascending trend during the last decade. Minimally invasive techniques for diagnosis and treatment, advances in radiation therapy, targeted therapies, increasing accessibility of immunotherapy have all contributed to extended clinical outcomes(3).

Widely available targeted therapies include the following alterations: EGFR mutations, ALK translocations, ROS1 rearrangements, BRAF, RET, ERBB2 and NTRK1/2/3 mutations. In advanced or metastatic disease setting, it is highly recommended to pursue biomarker testing in order to determine which patients may benefit from the available targeted therapies. The eligibility for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) is determined by PD-L1 testing, with specific cut-offs, for a better selection of accessible therapies(4).

Intensive research has shown that PD-L1 inhibitors (programmed death ligand 1) and PD-1 inhibitors (programmed death 1) are effective in first line for advanced or metastatic NSCLC setting. The first approved immune checkpoint inhibitor for second line in metastatic setting of NSCLC was nivolumab. This drug showed a significantly higher overall survival (OS) rate at six months compared to the standard chemotherapy with docetaxel(5). The therapeutic management of NSCLC has been substantially modified by the development of immune checkpoint inhibitors: nivolumab, pembrolizumab, durvalumab and atezolizumab. These agents have shifted the standard chemotherapy therapies from first line to second line and beyond, marking a new era in the therapeutic management of non-small cell lung cancer(6).

More recent guidelines have even moved immunotherapy from second line in metastatic NSCLC to front line in the neoadjuvant setting. Still, a high proportion of NSCLC eventually will progress, and the need to establish tailored management options for second-line, third-line and even for fourth-line therapy is becoming increasingly high(7).

However, randomized controlled studies enroll patients following a precise protocol, and their results may differ in terms of population heterogeneity from clinical practice. Furthermore, the need to corelate and corroborate randomized controlled trial (RCT) data with real-world evidence (RWE) is also becoming a standard of care, for a better understanding of the patients’ profiles, effectiveness of therapy, management of adverse events and cost management.

In Romania, the reimbursement of healthcare costs for immune checkpoint inhibitors started in 2017, with nivolumab for metastatic melanoma therapy, quickly followed by approval and reimbursement in pre-treated metastatic NSCLC(8).

Thus, the aim of this study is to determine the real-world therapeutic value of nivolumab in metastatic setting, in the second line and beyond. For this purpose, we included and investigated the medical records of thirty-four patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer from the “Prof. Dr. Alexandru Trestioreanu” National Institute of Oncology, Bucharest. We intend to assess the therapeutic value, safety profile, survival benefit and progression-free interval of disease. Of note, the recommended dosage in 2018 was 1 mg per kilogram every two weeks, not the today standard, which is 240 mg every two weeks.

Methodology

Study design

This has been a single-center retrospective cohort study conducted between January 2018 and December 2020, right after the approval of nivolumab in Eastern Europe for the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. The inclusion criteria were: adult patients (over 18 years of age) with advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Their therapy must have included immune checkpoint inhibitors (nivolumab) monotherapy or combination with chemotherapy as second line or beyond. The participants were assessed for overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS) for nivolumab and for standard chemotherapy, as well as for the safety profile of nivolumab. The response to therapy was assessed clinically and imagistically, according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 4.0 and the RECIST criteria.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, we used the R programming language, version 3.6.2, and some graphs and tables were drawn using Excel application in the Microsoft 365 for Enterprise pack. To evaluate the type of distribution, we used Shapiro-Silk test with a significance threshold of 0.05 (if p>0.05, the data is considered to be normally distributed and, therefore, parametric tests can be used). To compare the independent lots, we used two independent sample t-test and Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney test. When analyzing more than two subgroups, we used the ANOVA test (if normal distribution of numerical data) or Kruskal Wallis test (if abnormal distribution of data). To compare proportions, we used either chi-squared test, or Fischer test. For calculating survival values, we used Kaplan-Meier curve, both individually and for independent variables. For comparing Kaplan-Meier curves, we used log-rank test (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test). Progression-free survival was calculated as the time from the first initiation of immunotherapy with nivolumab to disease progression or death from any cause. In the medical files, the reports for disease progression were documented, both clinically and radiographically, using RECIST 1.1 criteria. We must mention that the data set was not quite balanced, due to the small sample size.

Results

Patients and tumoral characteristics

A total of 34 patients were included. The majority of them were males (79%), with a median age of 65.5 years old (range: 42-75). We found no statistically significant differences for age regarding one gender or the other (W=115; p=0.3934).

Patients’ distribution regarding gender and smoker status was 79% for male smokers and 21% for non-smokers. The proportion of smokers was statistically higher than the one for non-smokers (p=0.02044).

The histopathologic distribution of cases identified the majority of non-squamous NSCLC, with 56% of patients, and 44% with squamous carcinoma (X-squared=0.52941; df=1; p=0.4669) – Figure 1.

Distribution of metastases

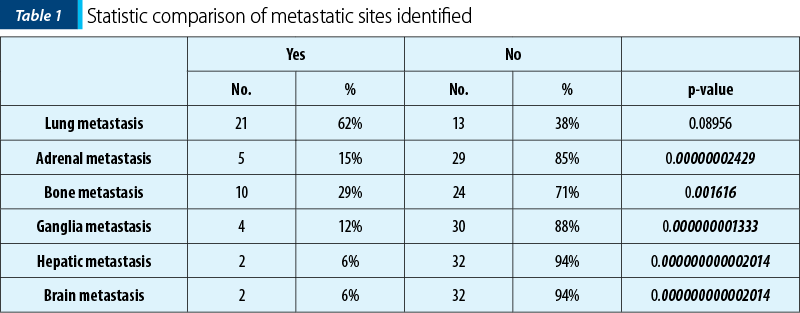

The patients were grouped by types of metastatic sites that have been identified in the lot. We can observe that most of the participants had lung metastases (Table 1).

Comorbidities

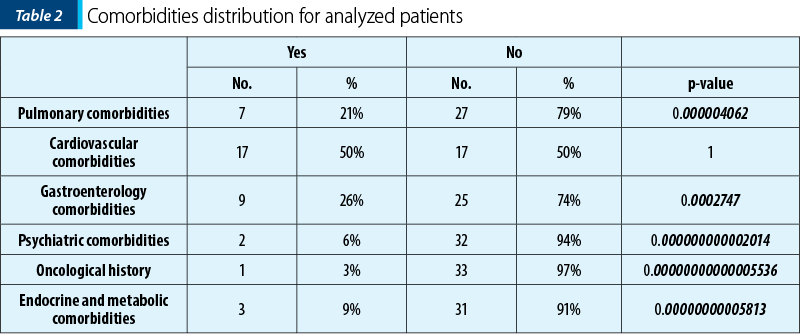

In the real-world setting, most patients have significant comorbidities, mostly cardiovascular and metabolic, given the fact that lung cancer is strongly associated with an unhealthy lifestyle, obesity, smoking habits and with high blood pressure, according to Table 2.

Therapy sequencing characteristics

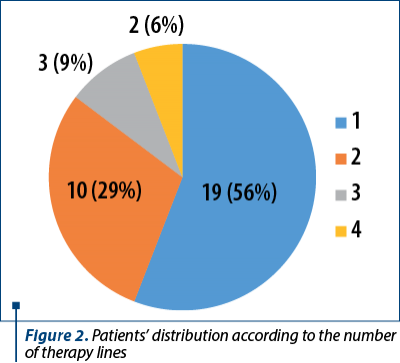

All the included participants received first-line therapy (34 patients) followed by second-line (29%), third-line (9%) and fourth-line therapy (6%) – Figure 2.

First-line therapy

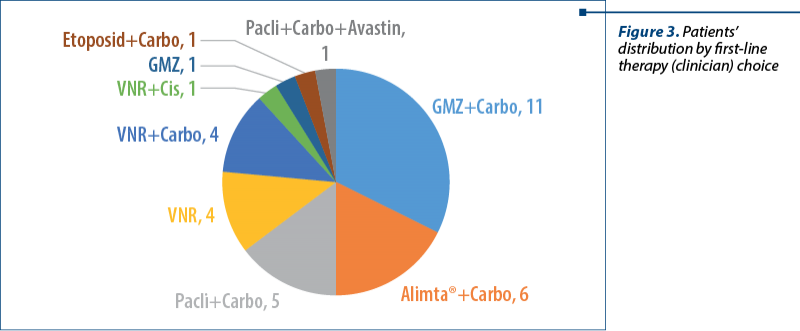

The distribution of first-line therapy choices is shown in the following pie chart diagram (Figure 3).

Most patients have received gemcitabine + carboplatin (GMZ+Carbo), followed by Alimta® + carboplatin (Alimta®+Carbo) and paclitaxel + carboplatin (Pacli+Carbo).

Vinorelbine + carboplatin (VNR+Carbo) and vinorelbine monotherapy (VNR) were equally used as presented in Figure 3.

Immunotherapy

All analyzed patient files and records have documented the administration of immunotherapy for advanced and metastatic NSCLC, second line and beyond. Immunotherapy with nivolumab was relatively well tolerated, 24 of the enrolled patients have not had any type of adverse events. The remaining 10 patients reported at least one type of adverse event, as follows: three patients reported pulmonary adverse events, followed equally by cardiovascular events, endocrine, rheumatological events and, in a lesser extent, hepatic adverse events. Of note, one patient reported a cardiovascular adverse event that required therapy with steroids and the permanent discontinuation of immunotherapy.

Therapeutic results

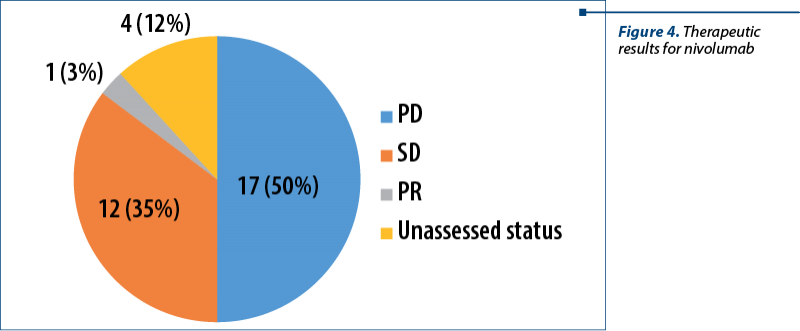

The therapeutic result with nivolumab was heterogeneous. None of the patients experienced complete response (CR). Half of the patients had progressive disease (PD), followed by those with stable disease (SD), and one patient with partial response (PR) – Figure 4.

Number of nivolumab cycles

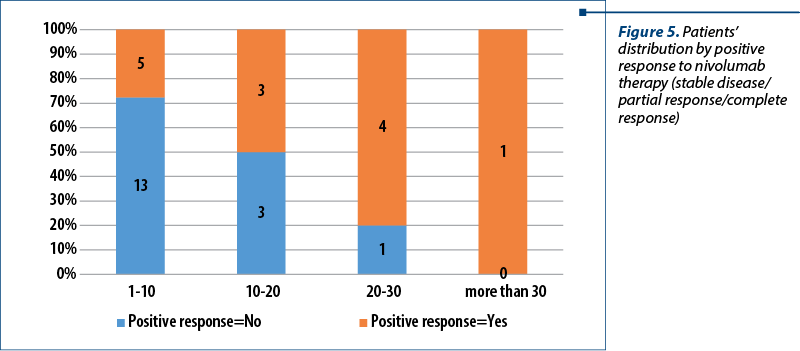

All of the enrolled patients received nivolumab in the second line and beyond, but the number of cycles varied from only one administration to thirty-one cycles of nivolumab. Most patients had a mean number of administrations between one and 10 cycles, followed by a mean number of administrations between 10 and 20 cycles, and followed by the next cut-off of 20-30 cycles. Only one patient received more than 30 cycles of nivolumab (31, to be exact). After assessing the disease status according to RECIST criteria, only 30 of the 34 patients could be evaluated, four of them had either been lost to follow-up or had inconclusive imagistic interpretations (X-squared=5.9276; df=NA; p=0.1129) – Figure 5.

Progressive disease after nivolumab therapy

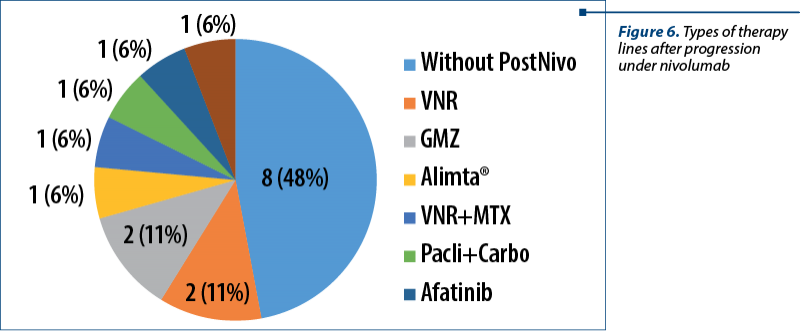

Seventeen of the enrolled patients had progressive disease under nivolumab immunotherapy. After disease progression, most of these could not benefit anymore after any other form of therapy due to a declined health status (ECOG 3). Of the patients who were able to tolerate further the therapy, two received vinorelbine (VNR) and two received gemcitabine (GMZ). Other types of therapy for each patient were administered, as presented in Figure 6. Of note, we included eight patients (n=8; 47%) who were unable to tolerate further the therapy after progression under nivolumab, for a better understating of the subsequent lines of therapy.

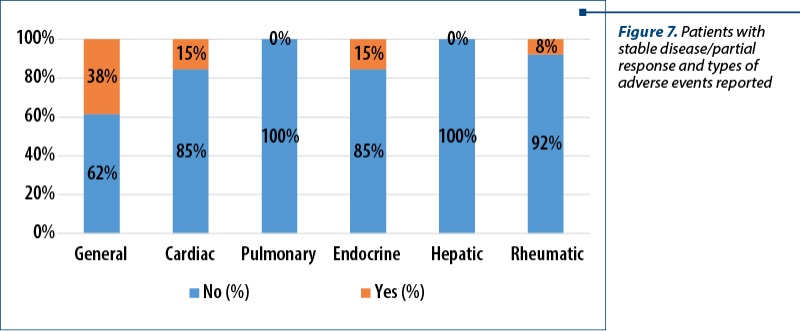

Adverse events for patients with stable disease and/or partial response

To sum up, we found that thirteen patients had either stable disease or partial response to nivolumab therapy, according to RECIST 1.1 criteria. Regarding these adverse events, we designed the following table to reflect the general situation with types of reactions noted in the medical files by the caring physicians (Figure 7).

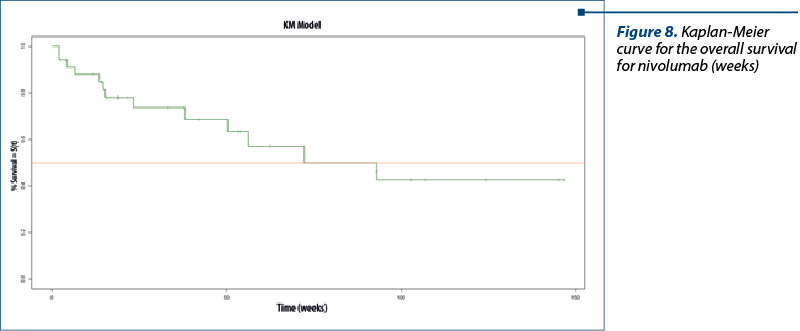

General overall survival

For estimating the overall survival (OS), we had to use a surrogate marker. This surrogate marker is represented by the difference between the date of permanent dismissal from the records (registered in the medical documentation) and the date of enrolment for therapy initiation (also registered in the medical records). The median OS was 32.57 months, but with extreme high values. Most patients (75%) had a median OS below 45.55 months. We grouped the participants depending on OS values into four quartiles:

-

Very small (<12.46) – quartile 1

-

Small (<24.43) – median or quartile 2

-

Medium (<45.55) – quartile 3

-

Significantly high – the rest.

The overall survival for nivolumab therapy was calculated as the time from the first initiation of nivolumab to the date of death or loss to follow-up, whichever came first. From the total of 34 patients, 13 deceased during the course of our study. The median time was 72.3 weeks (18.07 months). The confidence interval (CI) was 95%, between 12.5 months and infinite (NA). This fact is common when dealing with a small sample size (number) of patients – Figure 8.

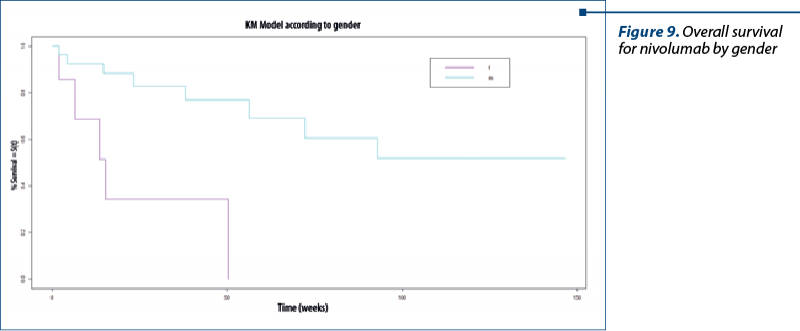

Overall survival for nivolumab by gender

We have summarized the survival graph and the Kaplan-Meier (KM) overview for each of the two variables. The median value for women was 15.3 weeks (3.8 months). For men, this value could not be reached (not available for calculation; NA). There were registered significative results between women and men (Chisq=611.1 on 1 degrees of freedom; p=0.0009) – Figure 9.

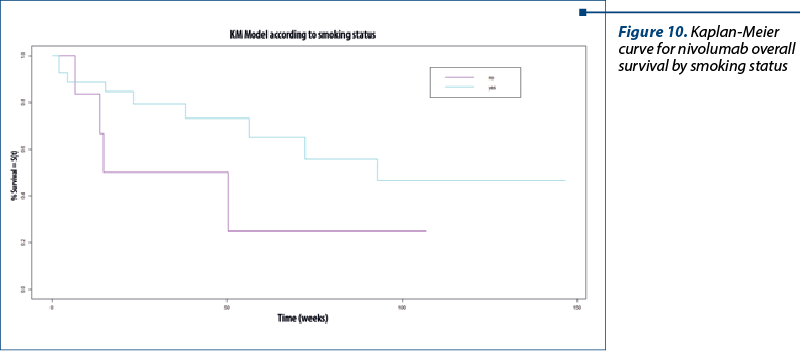

Overall survival for nivolumab by smoking status

The median value for non-smokers was 32.5 (8.12 months), and for smokers the median value was 93 weeks (23.25 months; p=0.1) – Figure 10.

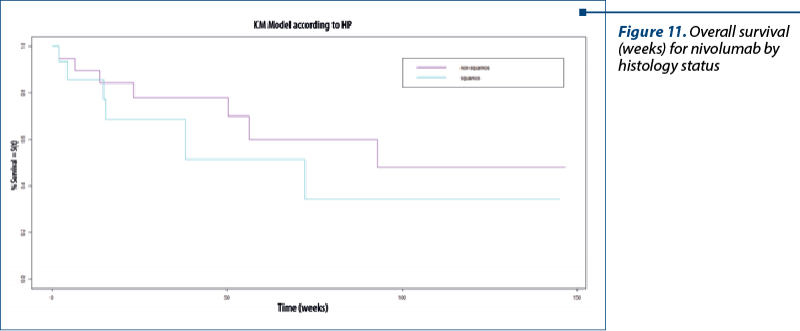

Overall survival for nivolumab by histopathology

We divided the patients by squamous and non-squamous histology. The median value for squamous carcinoma was 72.3 weeks (18.1 months), and for non-squamous NSCLC the histology was 93 weeks (23.25 months; Chisq=0.7 on 1 degree of freedom; p=0.4) – Figure 11.

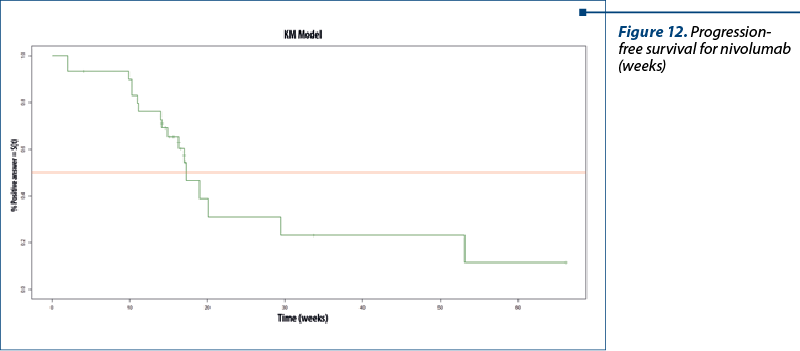

Progression-free survival for nivolumab

Of the total of 34 patients, four couldn’t be evaluated; therefore, we have excluded them from analysis and 17 patients had progressive disease (56.67%); 13 patients (43.33%) had positive therapeutic response (noted as stable disease or partial response).

The median was 17.3 weeks (4.3 months), with 95% CI, between 14.9 weeks (3.7 months) and infinity (NA), because of the small sample size studied here – Figure 12.

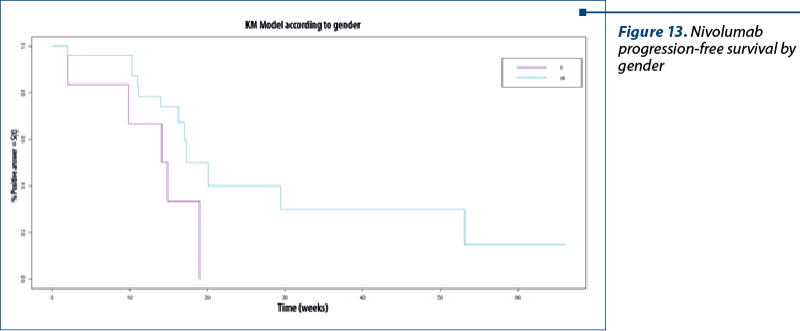

Nivolumab progression-free survival by gender. The median for women was 14.5 weeks (3.6 months) and for men, the median was 17.3 weeks (4.3 months; Chisq=3.7 on 1 degree of freedom; p=0.05) – Figure 13.

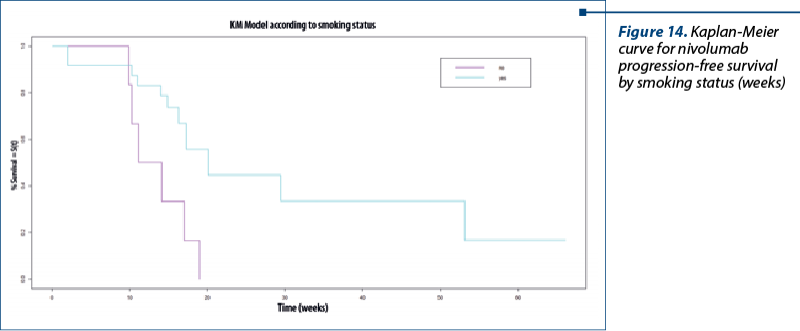

Progression-free survival for nivolumab by smoking status. The median for non-smokers was 12.6 weeks (3.1months). For smokers, we found this value to be 20.1 weeks (5 months; Chisq=6.6 on 1 degree of freedom; p=0.01) – Figure 14.

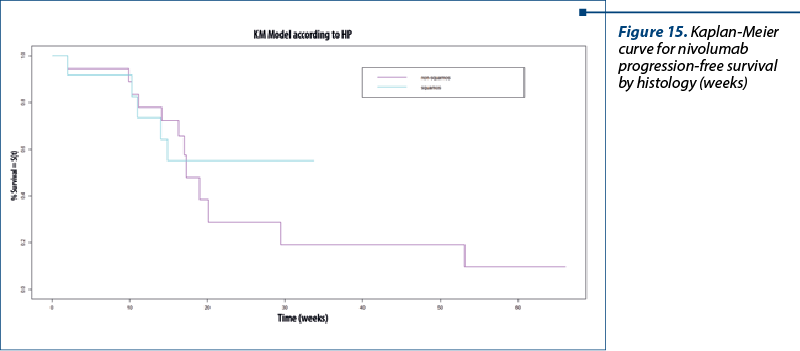

PFS for nivolumab by histology. The median for the non-squamous type was 17.3 weeks (4.3 months) and for the squamous type, it was not reached (NA; Chisq=0 on 1 degree of freedom; p=0.9) – Figure 15.

Discussion

In terms of survival (OS and PFS), we found similar results with well-known studies such as Check Mate 017, whose results were median OS of 9.2 months (95% CI; 7.3 to 13.3), and Check Mate 075, with median overall survival of 12.2 months (95% CI; 9.7 to 15)(9,10). More favorable responses were associated with a good performance status, male gender, smoker status and non-squamous histology and fewer comorbidities, similar to the findings of Zhao et al.(11) We did not find hyper-progressive disease and none of the patients included reached the complete response (CR) to immunotherapy. This is somewhat consistent with the findings of literature reviews for Check Mate 017, 057, 003 and 003, where only seven complete responses have been achieved in the entire study population of 664 patients(12). We found that nivolumab was relatively well tolerated, with just one serious adverse event that needed the permanent discontinuation of immunotherapy. Like in other findings(13), we can confirm that immunotherapy with nivolumab mostly induced pulmonary and cardiovascular adverse events, but manageable and well tolerated. What is interesting is that seventeen of the enrolled patients (50%) had progressive disease under nivolumab immunotherapy, and almost all could not benefit further from any other form of therapy. We ask ourselves the question of how to correctly identify patients who will mostly benefit from immunotherapy. And, furthermore, after disease progression, could these patients still be able to tolerate other lines of therapy?

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Who. The Global Cancer Observatory, 2020. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/15-Lung-fact-sheet.pdf. [Accessed 15 11 2022].

-

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. Epub 2021 Jan 12. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 Jul;71(4):359.

-

Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, Bonaventure A, Valkov M, Johnson CJ, Estève J, Ogunbiyi OJ, Azevedo E Silva G, Chen WQ, Eser S, Engholm G, Stiller CA, Monnereau A, Woods RR, Visser O, Lim GH, Aitken J, Weir HK, Coleman MP; CONCORD Working Group. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37,513,025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1023-1075. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3.

-

NCCN Guidelines, 2022. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf. [Accessed 15 November 2022].

-

Kazandjian D, Suzman DL, Blumenthal G, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Nivolumab for the Treatment of Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer with Progression On or After Platinum-Based Chemotherapy. Oncologist. 2016;21(5):634-642. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0507.

-

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540-1550. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7.

-

Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(21):1973-1985. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2202170.

-

Dagenais S, Russo L, Madsen A, Webster J, Becnel L. Use of Real-World Evidence to Drive Drug Development Strategy and Inform Clinical Trial Design. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111(1):77-89. doi:10.1002/cpt.2480

-

Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123-135. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1504627.

-

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627-1639. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1507643.

-

Zhao W, Jiang W, Wang H, He J, Su C, Yu Q. Impact of Smoking History on Response to Immunotherapy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:703143. Published 2021 Aug 23. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.703143.

-

Antonia SJ, Borghaei H, Ramalingam SS, et al. Four-year survival with nivolumab in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):1395-1408. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30407-3.

-

Morabito A. Second-line treatment for advanced NSCLC without actionable mutations: is immunotherapy the ‘panacea’ for all patients?. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):24. doi:10.1186/s12916-018-1011-0.