Sepsis, dyspnea and cystic cardiac mass – the importance of medical imaging in the diagnostic algorithm

Sepsis, dispnee şi masă cardiacă chistică – importanţa imagisticii în algoritmul diagnostic

Abstract

A 58-year-old woman presented with signs of sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. A cerebral and thoraco-abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) evaluation revealed the presence of a cardio-pericardial mass attached to the free wall of the right ventricle, with CT suggestive criteria of hydatid cyst. No involvement of other organs was noticed, but a segmental pulmonary embolism was also diagnosed after the CT scan. Echocardiography showed the intracardiac belonging of the cyst, therefore cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used for a thorough assessment. The patient underwent surgical resection with pericardial patch repair, with a favorable postoperative evolution.Keywords

cardiac cystic massCTcardiac MRIpulmonary embolismhydatic cardiac cystRezumat

O femeie în vârstă de 58 de ani s-a prezentat cu semne de sepsis şi coagulare intravasculară diseminată. Examinarea CT cerebrală şi toraco-abdomino-pelviană cu substanţă de contrast iodată a demonstrat prezenţa unei mase chistice cardiopericardice ataşate peretelui liber al ventriculului drept, având aspect CT sugestiv pentru un chist hidatic. Nu s-a decelat implicarea altor organe, însă, odată cu examinarea CT, a fost diagnosticat şi un tromboembolism pulmonar segmentar. Ecografia cardiacă a arătat apartenenţa intracardiacă a chistului, astfel încât, ulterior, s-a efectuat o examinare de tip cardio-RMN, pentru o analiză mai amănunţită. Pacienta a fost operată, efectuându-se excizia chistului şi reconstrucţia peretelui ventriculului drept cu petic de pericard heterolog, cu evoluţie postoperatorie favorabilă.Cuvinte Cheie

masă cardiacă chisticăCTcardio-RMNembolie pulmonarăchist hidatic cardiacIntroduction

Human cystic echinococcosis (CE) – also known as hydatid disease – is a zoonotic parasitic disease caused by the adult or larval stage of cestodes belonging to the Echinococcus genus. Humans become infected in a “hand-to-mouth” manner and are considered intermediate hosts(1). It is considered to be transmitted almost exclusively by domestic animals, meaning that, in theory, it could be eradicated, but only little progress was achieved towards this goal(2). Being a zoonotic disease, where sheep act like intermediate hosts and dogs and wolves are the definitive hosts, sheep-raising communities have a higher risk to encounter the disease, Romania still representing a hyperendemic region(3). The most commonly affected organs are the liver and the lungs, accounting for more than 90% of the cases, but other organs, like the kidneys, spleen, peritoneal cavity and the brain, can be affected (2-3% each)(4). Cardiac involvement is a rare event (1%), in most cases affecting the left ventricle as primary location(5). Some of the symptoms can be represented by arrhythmic events, fatigue, shortness of breath, but many patients are asymptomatic and the diagnosis is made incidentally. Most often, a multidisciplinary approach is used in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients, involving a cardiologist, a parasitologist, a radiologist and, in some cases, a cardiovascular surgeon.

Case presentation

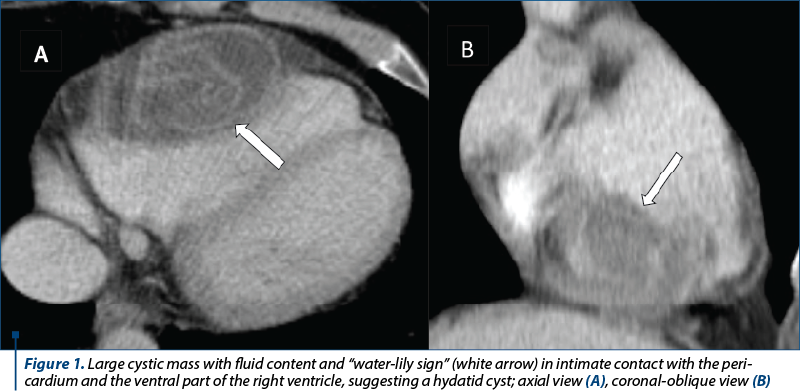

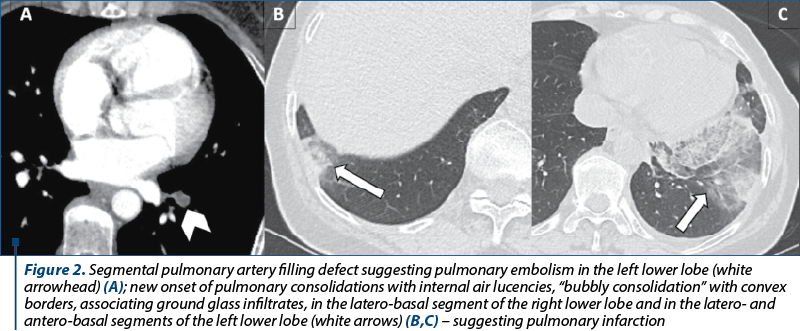

A 58-year-old female, with history of nausea, vomiting, dizziness, syncopal episodes and few rash episodes, was admitted for clinical signs of sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Her family history was unremarkable, denying alcohol consumption, smoking and the use of other illicit drugs. Considering the acute presentation, a cerebral and thoraco-abdominal-pelvic CT evaluation using iodine contrast agent was performed, showing a cystic mass with smooth borders, fluid content and a detached hydatid membrane with the pathognomonic CT “water-lily sign” (Figure 1), representing membrane complete detachment, consistent with cardiac hydatid disease. No other organs showed obvious signs of involvement. Moreover, segmental filling defects were observed at the site of the segmental arteries tributary to the antero-basal segment of the lower left pulmonary lobe, respectively the latero-basal segment of the right lower lobe, suggesting segmental pulmonary embolism (Figure 2A).

IgE serology was slightly elevated, measuring 3.74 UI/ml versus 1.1 UI/ml (normal limit). Due to the septic state, antibiotic therapy was initiated, using meropenem and vancomycin, showing symptoms’ alleviation. Echocardiography revealed a cystic mass located in the right ventricular free wall. The follow-up CT scan after seven days of treatment showed the onset of minimal bilateral pleural effusion and pulmonary changes suggesting pulmonary infarction (Figure 2 B, C).

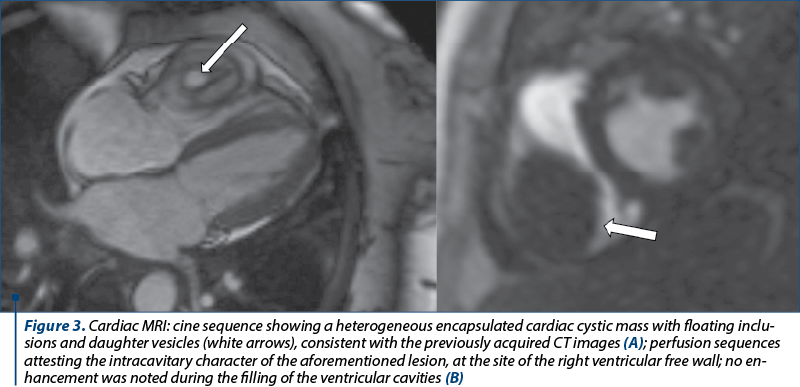

Although the CT findings were eloquent for the diagnosis of hydatic cyst, a cardiac MRI was performed for a better lesion assessment. The MRI showed an encapsulated intramyocardial cystic mass, with hypointense walls, heterogeneous content with serpiginous, floating inclusions suggesting detached proliger membrane and daughter cysts (Figure 3). Dynamic sequences were able to precisely delineate the aforementioned mass, showing the intracavitary extension of the lesion (Figure 3). No valvular involvement was noticed. Although the right ventricle was deformed, both ventricles had normal volumes and systolic function. Minimal tricuspid regurgitation was noticed. Both atria were normal. After the injection of contrast agent (gadolinium), no LGE (late gadolinium enhancement) was noticed, indicating the absence of fibrotic scars.

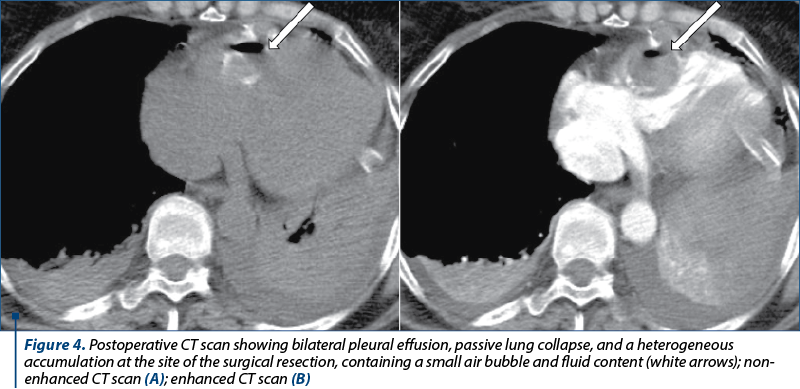

Following consultation with the parasitological expert, albendazole was initiated but, due to signs of parasitic activity (one episode of hives and shiver, in the absence of fever) with persistent negative blood cultures, surgery approach was considered. Preoperative invasive coronary angiography was performed for ruling out any potential previous coronary stenosis. No anomalies were noticed; therefore, the patient underwent surgical excision of the cystic mass, with right ventricular wall repair using a pericardial patch (postoperative CT exam – Figure 4). The postoperative evolution was favorable and the patient was discharged.

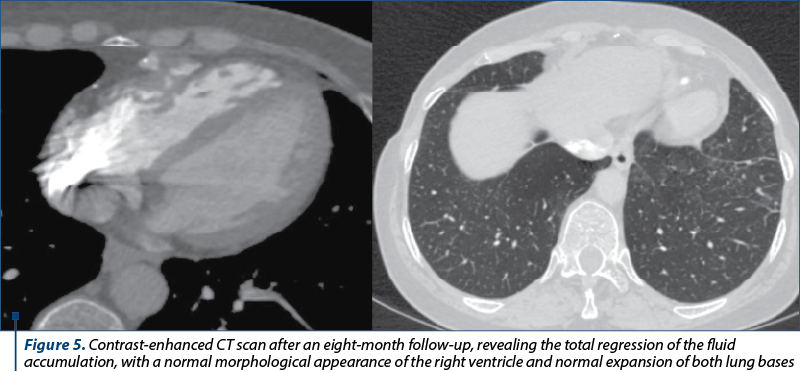

Eight months after the surgery, the patient returned accusing shortness of breath and reduced effort tolerance. A new embolic episode was suspected; therefore, a dual energy CT scan was performed, showing no signs of pulmonary embolism, a clear recovery of the pulmonary parenchyma and the remission of the ventricular accumulation (Figure 5).

Transesophageal echocardiography showed normal sized ventricles and normal systolic function, minimal tricuspid regurgitation and no signs of pulmonary hypertension. Exercise ECG was performed to quantify the described symptoms, revealing a good effort tolerance of the patient (11.5 METs).

Discussion

In the presence of a cystic cardiac mass, a hydatid disease is not the first obvious diagnosis. According to literature, the most common benign cardiac tumor is represented by myxoma (more than 50% of the cases)(6). Although myxomas are most often solid in nature, in very rare cases a cystic appearance is possible(7). The differential diagnosis consists of bronchogenic cysts, pericardial cysts, and (as presented in this case) hydatid cysts. Other differential diagnosis is done with malignant cystic cardiac tumors such as angiosarcomas in which cystic, necrotic and solid components are present. Pathognomonic findings like the “water-lily sign” or daughter cysts are important imaging features that might bring important diagnosis value. But even in those rare cases of cardiac hydatid disease, the most common location is the lateral wall of the left ventricle (up to 75% of cases), making our case an exceptionally rare occurrence(8). Often, the disease may remain silent, appearing as an incidental finding on routine exams, but sometimes it may be clinically apparent. Symptoms like fever, vomiting, nausea or rash may hint at the infectious nature of the disease, or they may be caused by the compressive character of the lesion, especially in high-volume cysts. These may include heart failure, atrioventricular block, arrhythmia, atrioventricular regurgitation, or even coronary narrowing(9). Other findings – also observed in this case – may include pulmonary embolism, infection, pleural and/or pericardial effusion, and in most severe cases, anaphylaxis or even death.

Conclusions

Echocardiography remains the first imaging modality to diagnose a cystic cardiac mass, allowing for a fast and cheap assessment not only of the location of the lesion, but also of the potentially hemodynamic impact caused by the exerted mass effect.

Specific CT findings confirm the hydatic nature of the cystic mass, and help in the assessment of the great mediastinal vessels, especially when a dual source technique is used, improving the sensitivity in detecting segmental and subsegmental pulmonary emboli. In addition, a complete evaluation of other organ involvement can be achieved using a multislice CT scan.

Cardiac MRI is a useful tool, but it is not as readily available as echocardiography. Currently, it is considered the method of choice when assessing the cardiac function and cardiac volumes. It can precisely assess lesion extension, its structure and potential complications, allowing also for myocardial structure study when gadolinium-based contrast agent is used.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Craig PS, McManus DP, Lightowlers MW, et al. Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(6):385-394. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70134-2.

-

Romig T, Dinkel A, Mackenstedt U. The present situation of echinococcosis in Europe. Parasitology International. 2006;55:S187–S191. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.028.

-

Mitrea IL, Ioniţă M, Wassermann M, Solcan G, Romig T. Cystic echinococcosis in Romania: an epidemiological survey of livestock demonstrates the persistence of hyperendemicity. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012 Nov;9(11):980-5. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1237.

-

McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, Bartley PB. Echinococcosis. The Lancet. 2003; 362(9392):1295–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14573-4.

-

Firouzi A, Neshati Pir Borj M, Alizadeh Ghavidel A. Cardiac hydatid cyst: A rare presentation of echinococcal infection. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2019;11(1):75-77. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2019.13.

-

Paraskevaidis IA, Michalakeas CA, Papadopoulos CH, Anastasiou-Nana M. Cardiac tumors. ISRN Oncol. 2011;2011:208929. doi: 10.5402/2011/208929.

-

Hwang JJ, Lien WP, Kuan P, Hung CR, How SW. Atypical Myxoma. Chest. 1991;100(2):550–551. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.2.550.

-

Beshlyaga VM, Demyanchuk VB, Glagola MD, Lazorishinets VV. Echinococcus cyst of the left ventricle in 10-year-old patient. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21(1):87. doi:10.1016/s1010-7940(01)01073-9.

-

Dursun M, Terzibasioglu E, Yilmaz R, et al. Cardiac hydatic disease: CT and MRI findings. AJR. 2008;190(1)226-232. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2035