Enterocele represents the protrusion of the small intestine into the upper wall of the vagina. Pelvic organ prolapse has a prevalence of 3-6%. Most women have stage I (43.3%) or stage II prolapse (47.7%). The main causes for the occurrence of pelvic organs prolapse are: pregnancy, vaginal birth, menopause (ageing, hypoestrogenism), chronic raised intraabdominal pressure (chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, constipation, obesity), pelvic wall trauma, genetic factors (race, connective tissue disorder), spina bifida. In this article, we present a rare case of isolated enterocele without the association of the rectocele.

Enterocel voluminos – studiu de caz

Voluminous enterocele – a case report

First published: 27 decembrie 2018

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Gine.22.4.2018.2143

Abstract

Rezumat

Enterocelul reprezintă protruzia intestinului subţire la nivelul peretelui superior al vaginului. Prolapsul genital are o prevalenţă de aproximativ 3-6%. În majoritatea cazurilor, peste 90%, este în stadiul I sau II, cu o incidenţă de aproximativ 43,3% pentru stadiul I şi de aproximativ 47% pentru stadiul II. Principalele cauze de apariţie ale enterocelului sunt: sarcina, naşterea pe cale vaginală, menopauza, din cauza îmbătrânirii şi a hipoestrogenismului, creşterea cronică a presiunii intraabdominale (boală cronică pulmonară, constipaţie, obezitate), traume ale planşeului pelvian, factori genetici, spina bifida. În acest articol aducem în discuţie un caz rar de enterocel fără asocierea rectocelului.

Introduction

Enterocele represents the protrusion of the small intestine into the upper wall of the vagina. The pelvic floor is a group of muscles that form a kind of hammock across the pelvic opening. Pelvic organ prolapsed is a result of weakening of the perineal structures such as muscle, ligaments and connective tissue. About one-third of all women are affected by prolapse or similar conditions over the time. Pelvic organ prolapse has a prevalence of 3-6%. In most cases, more than 90%, there is a stage I or stage II disorder. Stage I is encountered in about 43.3% of cases, while stage II is encountered in about 47.7% of cases(1). The main causes for the occurrence of pelvic organs prolapse are: pregnancy, vaginal birth, menopause (ageing, hypoestrogenism), chronic raised intraabdominal pressure (chronic pulmonary obstructive disease, constipation, obesity), pelvic wall trauma, genetic factors (race, connective tissue disorder), spina bifida(2).

The symptoms occur according to the involved prolapsed organs. For instance, if the bladder is involved, the condition is known as cystocele, and the main symptomatology involves the urinary tract (leaking of urine or urge to urinate). If the main organ involved is the small bowel, we refer to this condition as enterocele(2).

The diagnosis is usually made by clinical examination, and the treatment can be conservatory or surgical.

Case report

A 81-year-old patient was admitted to our hospital with pain and perineal discomfort, all because of a exteriorized vaginal formation, which occurred approximately two years ago, and which had a progressive enlargement since then. From her medical records, the patient related a vaginal surgical intervention in 1996, without any medical proof recorded. Between 2015 and 2017 the patient had a vaginal pessary, for conservatory treatment of the vaginal prolapsed, which has been extracted because of its lack of efficiency. From the personal data of the patient, is important to be pointed that she had her first period at the age of 13, she had two vaginal births and the menopause installed at 51 years old. From the medical records, the patient relates that she suffered some surgical interventions, such as a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, appendicectomy, left salpingectomy for tubal ectopic pregnancy in 1970, anterior colporrhaphy and colpoperineorrhaphy in 1996. She has type 2 diabetes mellitus and high blood pressure.

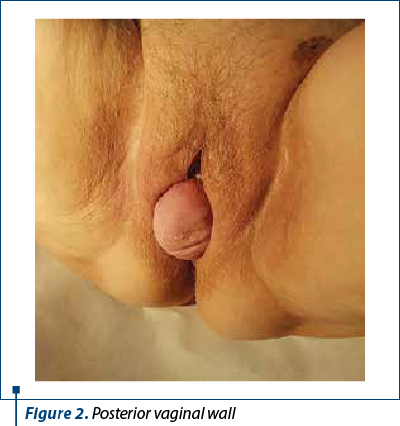

The clinical examination shows a third-degree uterine prolapsed (Figure 1), a high protrusion of the posterior vaginal wall (Figure 2) and a protrusion of 4-5 cm of the vaginal wall when the patient is positioned in dorsal decubitus and the Valsalva maneuver. The clinical examination also revealed the uterine size of 4.5/3 cm, with a slight cervical elongation, the anterior colporrhaphy scar, the colpoperineorrhaphy scar, and by rectal examination, rectum absence in the posterior colpocele.

All those clinical data were sufficient to establish the diagnose of third-degree uterine prolapsed and voluminous enterocele. The patient was informed about all treatment options and decided that a surgical intervention was imposed.

The surgical options were: correction of the prolapse and of the enterocele by laparoscopic hysteropexy, or remaking and repositioning of the pericervical ring followed by the remediation of the enterocele through vaginal way.

The preoperative balance sheet, the anesthetic evaluation (ASA 4 risk), followed by a proper conversation with the patient were decisive for choosing the type of surgical treatment. The fact that the patient was old and she had to lay down for a long period of time in Trendelemburg position were strong arguments for choosing the vaginal way instead of laparoscopic surgery.

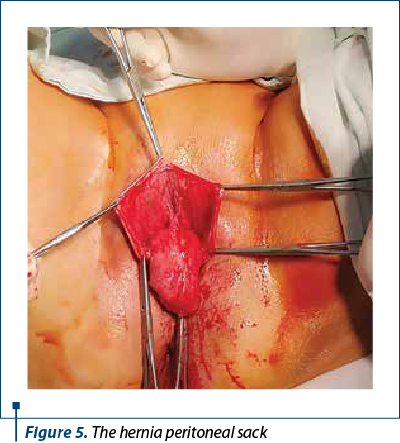

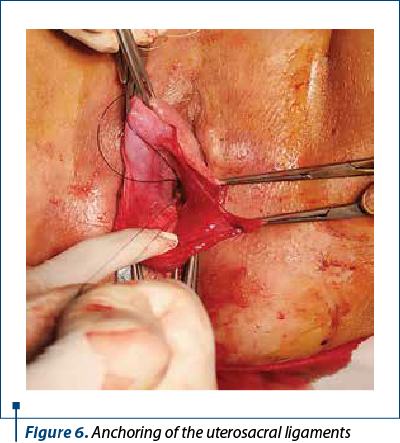

The surgical intervention started with the liquefracture of the vaginal posterior mucosa and a median incision from the cervix to 3 cm away from the vaginal introitus. After the vaginal mucosa detachment, the hernia peritoneal sack which contained ileal loops was highlighted (Figure 5). The uterosacral ligaments were highlighted with two number 0 polypropylene monofilament wires after the opening of the hernia sack (Figure 6).

The anchorage wires of the uterosacral ligaments are crossed by posterior face of the uterine isthmus and transfixiant by recto-uterine pouch vaginal mucosa. After anterior colpotomy, the vaginal mucosa is detached until the ischiadicus brunch. A polypropylene monofilament mesh was crossed on the posterior face of the uterine isthmus transfixiant by cardinal ligaments basis. The mesh was fixed by out-in transobturator-tape-procedure. Anterior and posterior colphorrhaphy and perineoplasty were performed after the excessive vaginal mucosa was removed. The mesh was thightened and the hystero suspension wires to uterosacral ligaments were tighted too. The intervention lasted 75 minutes. The anesthesia type was locoregional. The postsurgical result was good.

Conclusions

The pelvic-genital static disorder that we presented appeared due to structural defects of the posterior compartment fascia and ligaments (uterosacral ligaments, cardinal ligaments and recto-vaginal fascia)(3).

The type of intervention respected the corection principles for the pelvic-genital static in conformity with the associated anatomical defects(4).

The particularity of this case consisted in the fact that it was a rare case of isolated voluminous enterocele, without associated rectocele.

The main advantage for using vaginal way for fixing pelvic-genital static disorder is represented by the lower anesthetic risk compared to other surgical methods proposed for old women(5).

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Adam RA, Strohbehn K. Enterocele and masive vaginal eversion. Medscape, 2016.

- Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, MD, Halvorson LM, Bradshaw KD, Cunningham FG. Pelvic organs prolapse. Williams Gynecology, 2nd ed, Romanian Ed, Hipocrate, 2015:633-59.

- Goeschen K, Petros P, Muller Funogea A, Brătilă E, Brătilă P, Cîrstoiu MM. The women pelvic floor: functional anatomy, diagnosis and treatment acourding to integrative theory. Ed Universitară „Carol Davila”, 2016; Bucureşti, 5-132.

- Kovac SR, Zimmerman CW. Advances in reconstructive vaginal surgery. Lippincott Williams&Wilkins. 2012; 227-47.

- Brătilă P. Vaginal hysterectomy. Ed. Dobrogea, 2006; Constanţa, 119-31.