The last decades made an essential contribution to the knowledge of occupational risk factors on human reproductive function. Reducing exposure to these factors is a constant public health concern. This article exemplifies the main categories of risk factors for maternal and fetal health, the effects described in people exposed during the occupational activity, and the possibilities for intervention provided by current Romanian legislation. The multitude of occupational contexts in which these risk factors occur and the need to protect against harmful effects determine the intervention of the occupational physician after the employee notifies the employer about the pregnancy. Following this information, the occupational physician analyzes with the employer the presence of hazards in the workplace that could have undesirable effects on the pregnant woman. The purpose of this investigation is to find solutions to stop the exposure to any potential nuisance. If the exposure cannot be completely stopped, the occupational physician may use the pregnant woman’s right to maternity leave as a primary preventive measure. In conclusion, maternity leave is not similar to obstetric risk, medical leave or prenatal leave. However, knowledge of the legal framework and effective communication between the occupational physician, the obstetrician and the family doctor can help reduce the overall maternal risk.

Concediul medical pentru risc maternal: o intervenţie preventivă de medicină a muncii

The sick leave for maternal risk: a preventive occupational medicine intervention

First published: 24 mai 2022

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.70.1.2022.6506

Abstract

Rezumat

Ultimele decade au adus cu sine şi o contribuţie importantă la cunoaşterea factorilor de risc ocupaţionali asupra funcţiei de reproducere umană. Reducerea expunerii la aceşti factori este o preocupare constantă pentru sănătatea publică. În acest articol sunt exemplificate principalele categorii de factori de risc pentru sănătatea mamei şi a fătului, alături de efectele descrise la persoanele expuse în timpul activităţii profesionale, precum şi posibilităţile de intervenţie pe care le prevede legislaţia actuală din România. Multitudinea de contexte ocupaţionale în care apar aceşti factori de risc şi necesitatea protejării faţă de efectele nocive determină intervenţia medicului de medicina muncii în momentul în care angajata anunţă angajatorului despre existenţa sarcinii. În urma acestei informări, medicul de medicina muncii va analiza împreună cu angajatorul existenţa elementelor din condiţiile de muncă care ar putea avea efecte nedorite asupra femeii însărcinate. Scopul acestei investigaţii este găsirea unor soluţii pentru sistarea expunerii la orice noxă potenţială. Dacă expunerea nu poate fi sistată în întregime, medicul de medicina muncii poate uza de dreptul gravidei la concediu de risc maternal, ca măsură de prevenţie primară. În concluzie, concediul de risc maternal nu este similar cu concediul medical de risc obstetrical sau cu concediul prenatal. Cunoaşterea cadrului legislativ şi stabilirea unei comunicări eficiente între medicul de medicina muncii, medicul obstetrician şi medicul de familie pot contribui la reducerea în ansamblu a riscului maternal.

Hazards present in the workplace can have various negative effects on the evolution of pregnancy and on the development of the design product. These effects may occur during pregnancy, the postnatal period or at a distance of pregnancy through influences on the development of the offspring.

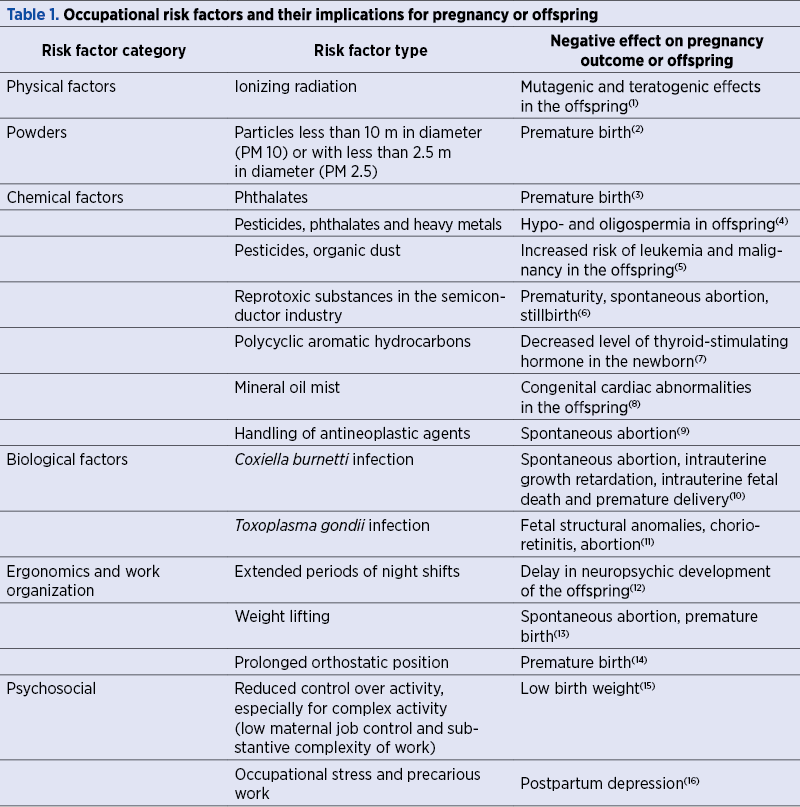

In principle, occupational risk factors are classified into physical, chemical, biological, ergonomic and psychosocial factors, and any of these can impact the course of pregnancy. Therefore, without an exhaustive analysis of the risk factors to which a pregnant woman is exposed during pregnancy or in the pre-pregnancy period, Table 1 exemplifies each of the aforementioned categories with studies showing the importance of the professional environment on pregnancy.

A literature review has shown the need to prioritize research on drugs with reprotoxic potential, metals, pesticides, organic solvents, phthalates and fluorinated compounds(17). However, in almost all professional contexts, there is a combination of risk factors.

The presence of these hazards in the workplace correlates with the number of days of sick leave during pregnancy. This has been confirmed by several studies published in recent years. For example, a study conducted in France on a population of 1495 pregnant women identified statistically significant differences for the following risk factors: prolonged orthostatism (above 1 hour), weight lifting (for more than 5 kg), climbing stairs, night shifts, exposure to chemicals, contact with patients or animals, or people who did not have a fixed-term employment contract(18). An increase in absenteeism was directly correlated with the number of occupational risk factors(19). In this study, also conducted in a high-income country, the occupational risk factors considered were ergonomic factors (prolonged orthostatic position, awkward positions, weight lifting) and psychosocial factors (workload, ability to control the activity). Postural constraints and the level of physical overload(20,21) were directly correlated with the number of days of medical leave. It should be noted that no sector of activity is excluded, including the medical field(21).

In general, women working in the industrial environment, generically called “blue-collars”, have an increased risk of sick leave compared to women working in services, administration, generically referred to as “white collars” (20,22). Studies showing that all occupational classes have a higher risk of sick leave than in the category of highly qualified professionals(23) or those with managerial positions(18) are in the same direction.

Unfortunately, we do not have such official statistics in Romania. However, such an analysis would be extremely important, as maternity risk leave is included in the legislation of our country for more than 20 years. Maternity risk leave is the leave enjoyed by the pregnant worker or the one who has recently given birth/the breastfeeding employee to protect their health and safety and/or that of their fetus or child(24). According to the same government ordinance, the pregnant employee is considered the woman who notifies the employer in writing of her physiological state of pregnancy and attaches a medical document issued by the family doctor or specialist attesting to this condition. The employer and the occupational physician evaluate the risks to which the employee is subjected at her workplace, draws up and signs the Risk Assessment Report. The employee receives information on maternity protection at work, which sets out the assessment results of the risks she may be subjected to at work and the additional protection measures that both the employer and the employee must comply with.

The employee may request maternity risk leave from the occupational physician from the beginning of the pregnancy if the employer cannot, for objectively justified reasons, assure the modification of her working conditions and/or work schedule or her assignment to other job tasks which will not represent a risk to the health or safety of the child and/or the fetus or child (according to the Maternity Protection Information at Work). Therefore, the occupational physician recommends this type of leave only if, for objective and justified reasons, the employer cannot change the conditions and/or schedule and/or workplace to eliminate the risks to the employee’s health, of the fetus or, as the case may be, of the child. The O.U.G. no. 96/2003 provisions do not apply, even though the employee submits recommendations from the family doctor or the specialist regarding the limitation/avoidance of certain activities/factors, if in the Risk Assessment Report no such activities/factors are identified.

Given the complexity and variety of occupational exposure, as well as the very specific legislative provisions on preventing the negative effects of occupational activity on pregnancy, closer collaboration is needed between occupational medicine, obstetrics-gynecology and family medicine, specialties that should work together more effectively for the benefit of the pregnant woman. It is necessary to develop communication procedures and improve the way healthcare is provided, including ensuring the possibility of interdisciplinary consultation of these specialists.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Shi L, Chia SE. A review of studies on maternal occupational exposures and birth defects, and the limitations associated with these studies. Occup Med (Lond). 2001;51(4):230-44.

-

Liu X, Ye Y, Chen Y, Li X, Feng B, Cao G, Xiao J, Zeng W, Li X, Sun J, Ning D, Yang Y, Yao Z, Guo Y, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Ma W, Du Q, Zhang B, Liu T. Effects of prenatal exposure to air particulate matter on the risk of preterm birth and roles of maternal and cord blood LINE-1 methylation: A birth cohort study in Guangzhou, China. Environ Int. 2019;133(Pt A):105177.

-

Hu JMY, Arbuckle TE, Janssen P, Lanphear BP, Braun JM, Platt RW, Chen A, Fraser WD, McCandless LC. Associations of prenatal urinary phthalate exposure with preterm birth: the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) Study. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(3):333-341

-

Istvan M, Rahban R, Dananche B, Senn A, Stettler E, Multigner L, Nef S, Garlantézec R. Maternal occupational exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals during pregnancy and semen parameters in adulthood: results of a nationwide cross-sectional study among Swiss conscripts. Hum Reprod. 2021 Jun 18;36(7):1948-1958

-

Patel DM, Jones RR, Booth BJ, Olsson AC, Kromhout H, Straif K, Vermeulen R, Tikellis G, Paltiel O, Golding J, Northstone K, Stoltenberg C, Håberg SE, Schüz J, Friesen MC, Ponsonby AL, Lemeshow S, Linet MS, Magnus P, Olsen J, Olsen SF, Dwyer T, Stayner LT, Ward MH; International Childhood Cancer Cohort Consortium. Parental occupational exposure to pesticides, animals and organic dust and risk of childhood leukemia and central nervous system tumors: Findings from the International Childhood Cancer Cohort Consortium (I4C). Int J Cancer. 2020 Feb 15;146(4):943-952

-

Choi KH, Kim H, Kim MH, Kwon HJ. Semiconductor Work and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Associated with Male Workers: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Work Expo Health. 2019;11;63(8):870-880.

-

Dehghani S, Fararouei M, Rafiee A, Hoepner L, Oskoei V, Hoseinif M.Prenatal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and effects on neonatal anthropometric indices and thyroid-stimulating hormone in a Middle Eastern population. Chemosphere. 2022;286(1): 131605

-

Siegel M, Rocheleau CM, Johnson CY, Waters MA, Lawson CC, Riehle-Colarusso T, Reefhuis J; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Maternal Occupational Oil Mist Exposure and Birth Defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997-2011. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(9):1560.

-

Nassan FL, Chavarro JE, Johnson CY, Boiano JM, Rocheleau CM, Rich-Edwards JW, Lawson CC. Prepregnancy handling of antineoplastic drugs and risk of miscarriage in female nurses. Ann Epidemiol. 2021 Jan;53:95-102.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.09.003.

-

Groten T, Kuenzer K, Moog U, Hermann B, Maier K, Boden K. Who is at risk of occupational Q fever: new insights from a multi-profession cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020:9;10(2):e030088.

-

Gonzalez C. Occupational reproductive health and pregnancy hazards confronting health care workers. AAOHN J. 2011 Sep;59(9):373-6. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20110825-04.

-

Wei CF, Chen MH, Lin CC, Guo YL, Lin SJ, Liao HF, Hsieh WS, Chen PC. Association between maternal shift work and infant neurodevelopmental outcomes: results from the Taiwan Birth Cohort Study with propensity-score-matching analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(5):1545-1555

-

Croteau A. Occupational lifting and adverse pregnancy outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77:496-505.

-

Cai C, Vandermeer B, Khurana R, Nerenberg K, Featherstone R, Sebastianski M, Davenport MH. The impact of occupational activities during pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(3):224-238.

-

Meyer JD, Warren N, Reisine S. Job control, substantive complexity, and risk for low birth weight and preterm delivery: an analysis from a state birth registry. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50(9):664-75.

-

Karl M, Schaber R, Kress V, et al. Precarious working conditions and psychosocial work stress act as a risk factor for symptoms of postpartum depression during maternity leave: results from a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1505.

-

Teysseire R, Brochard P, Sentilhes L, Delva F. Identification and Prioritization of Environmental Reproductive Hazards: A First Step in Establishing Environmental Perinatal Care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3):366.

-

Henrotin JB, Vaissière M, Etaix M, Dziurla M, Malard S, Lafon D. Exposure to occupational hazards for pregnancy and sick leave in pregnant workers: a cross-sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2017;29:12.

-

Sejbaek CS, Pedersen J, Schlünssen V, Begtrup LM, Juhl M, Bonde JP, Kristensen P, Bay H, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Hougaard KS. The influence of multiple occupational exposures on absence from work in pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(1):60-68.

-

Kalboussi H, Bannour D, Kacem I, Debbabi F, Haj Salah H, Mrizak N. Influence of occupational factors on pregnant women’s absenteeism in central Tunisia. Archives des Maladies Professionnelles et de l’Environnement. 2015;76(5):468-477.

-

Estryn-Behar M, Amar E, Choudat D. Sick leave during pregnancy: an analysis of French hospitals from 2005 until 2008 demonstrates the major importance for jobs with physical demands. Rech Soins Infirm. 2013;(113):51-60.

-

Alexanderson K, Hensing G, Carstensen J, Bjurulf P. Pregnancy-related sickness absence among employed women in a Swedish county. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1995;21(3):191-8.

-

Ariansen AM. Age, occupational class and sickness absence during pregnancy: a retrospective analysis study of the Norwegian population registry. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5):e004381

-

Ordonanţa de urgenţă a Guvernului 96 din 2003 actualizată privind protecţia maternităţii la locurile de muncă. Available at: https://www.iprotectiamuncii.ro/legislatie-protectia-muncii/oug-96-2003 (downloaded on 10.01.2022).