A chronic neuroimmunological disorder of the neuromuscular synapse, caused by the direct attack of antiacetylcholine receptor antibodies at the end of the motor plate, myasthenia gravis can be a diagnostic trap and a great challenge for any clinician. Being a multifaceted disease that affects the muscular system on different muscle groups, dramatically exhausting the patient, this disease makes its impact felt also in the obstetric practice. The expectant mothers with myasthenia gravis have their anxieties and insecurities about the various aspects of the manifestation of the disease during pregnancy and then on the newborn. At present, in our country, there are no official publications dedicated exclusively to this issue, which is why, through this article, we try to point out important aspects of myasthenia gravis, meant to support young mothers, neurologists, anesthetists and obstetricians.

Myasthenia gravis şi sarcina

Myasthenia gravis and pregnancy

First published: 23 decembrie 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.68.4.2020.4023

Abstract

Rezumat

Afecţiune cronică neuroimunologică a sinapsei neuromusculare, cauzată de atacul direct al anticorpilor antireceptor pentru acetilcolină la nivelul terminaţiilor plăcii motorii, myasthenia gravis poate fi o capcană de diagnostic şi o mare provocare pentru orice clinician. Fiind o boală cu multe faţete, care afectează sistemul muscular la nivelul unor diferite grupe de muşchi, epuizând dramatic pacientul, această maladie îşi face simţit impactul şi în practica obstetricală. Viitoarele mame miastenice au angoasele şi nesiguranţa lor, cu privire la diversele aspecte ale manifestării miasteniei pe parcursul sarcinii şi apoi asupra nou-născutului. În prezent, la noi în ţară nu există publicaţii oficiale consacrate şi dedicate exclusiv acestei problematici, tocmai de aceea încercăm, prin intermediul acestui articol, să punctăm unele aspecte importante ale myastheniei gravis, menite să vină în sprijinul tinerelor mame, medicilor neurologi, anesteziştilor şi obstetricienilor.

What is myasthenia gravis and how can it be diagnosed?

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder affecting nearly 1 million individuals worldwide(1), being diagnosed typically in the second and third decades of life. Myasthenia gravis is defined by muscle weakness caused by defective function of the acetylcholine (AChR) receptors at the neuromuscular junction(1,2) as a consequence of a direct autoantibodies attack against the AChR receptors(3). Tumors and thymus hyperplasia can cause an aberrant synthesis and production of these autoantibodies. The clinical severity of MG varies from pure ocular muscle involvement (ocular MG) to generalized muscular weakness (generalized MG).

The diagnosis of MG is made following clinical and physical examination and is confirmed by serum immunodiagnose to measure autoantibody levels. The diagnosis of myasthenia should be made carefully, by corroborating the clinical aspect and the clinical outcome of the patient.

The stages of the clinical diagnosis include the following aspects:

-

physical examination (myasthenic score QMG, adapted in our clinic after Cincă and Ion, in 1974);

-

electromyogram (repetitive nerve stimulation/single fiber electromyography);

-

laboratory tests – immunoserology, in order to detect the antibody titer;

-

chest computer scan for thymus.

Myasthenia gravis treatment and management during pregnancy

Generally, MG does not affect pregnancy to a considerable extent. There is no increased risk of low birth weight, spontaneous abortion or a given prematurity degree of the newborn, although an increased risk of premature rupture of membranes does exist in myasthenic women, the reason of which is not very clear enough and documented(4).

The pharmacologic treatment for MG is commonly centered on increasing the levels of AChR and decreasing the production of autoantibodies.

The medical treatment should not be interrupted during pregnancy; anyhow, it might need to be influenced depending on disease severity or exacerbations(5).

The ideal management of MG during pregnancy requires a multidisciplinary team participation, including obstetrician, anesthesiologist, neonatologist/pediatrician, also by assuring a good contact by the patient and relatives.

Other aspects that must be considered, but without detailing them in this article, are:

-

prenatal counseling;

-

antenatal care;

-

specific drugs- and pregnancy-related problems;

-

breast feeding (the impact and the effects of MG medication on lactation and breastfeeding safety).

Myasthenic crisis in pregnancy

Myasthenic crisis in the context of pregnancy is rare and requires unique management challenges for emergency physicians. In general, if the treatment of myasthenia during pregnancy is well dosed and administered, there are no complications. In case of a myasthenic crisis during hospitalization for childbirth or during labor (rarely), the means of intensive care are used. In the following, we will point out this important aspect for both intensivists and gynecologists. The histological constitution of the uterus is defined by the presence of smooth muscle, not being affected by the presence of ACh receptor antibodies, and vaginal delivery is desired and recommended(6,7). A possible myasthenic crisis during the hospitalization of the pregnant woman can be announced by the following pathophysiological features: acute onset cough, increased secretions, dyspnea, nasal congestion, sore throat, dysphagia, resting dyspnea and generalized weakness, increasing difficulty clearing her secretions. Generally, these symptoms worsen in the evening, being followed by the alterations of the specific vital signs given to this clinical context: blood pressure (sometimes), heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation/fraction of inspired oxygen by facial mask, arterial blood gasometry. Testing for rhinovirus/enterovirus can be useful, as well.

The respiratory testing is a helpful tool for the intubation prognostic, and should be taken seriously into account, given that early intubation is critical(8). There are unforeseen, emergency situations when plasmapheresis is needed. After the pregnancy plasmapheresis sessions, the patient must be transferred and supervised in an antepartum service. There is also an increased risk of preterm birth concerning congenital myasthenic syndrome, although this is the resultant of a polyhydramnios caused by the loss of fetal swallowing(9). Myasthenia has not been found to increase the risk of fetal death, growth restriction or preeclampsia(10). Still, as it happens, in preeclampsia or eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is contraindicated, as it affects the motor endplate, blocking acetylcholine release and worsening myasthenia.

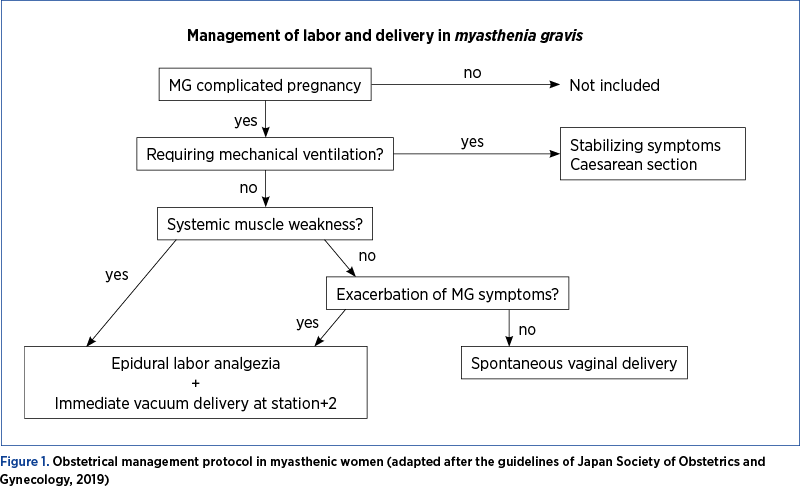

The effects of myasthenia on labor and delivery

One aspect that raises questions is the impact of labor and expulsion of the fetus, due to “the myasthenic muscle” contractions related to this physiological act. Pregnancy with myasthenia gravis is known to be correlated with an increased caesarean section rate, doubtless due to maternal fatigue in the course of labor. Even though the uterine muscles, which consist of smooth muscles, are barely affected in myasthenia gravis-complicated pregnancies, the voluntary muscle weakness can be aggravate due to the expulsive efforts during the second stage of labor, and fatigability can lead to respiratory distress(11). The patients can lose strength after the third expulsive effort. There are particular cases when the administration of oxytocic drugs and vacuum-assisted delivery are a beneficial option. The apparition of respiratory distress, bulbar symptoms and muscle weakness must be carefully checked during labor. Briefly, vaginal delivery in pregnant myasthenic woman should be encouraged. Caesarean delivery shall be carried out only for obstetrical reasons, as surgery might often associate the worsening of the disease and can even precipitate myasthenic crisis.

Anesthetic remarks

The preoperative evaluation of the myasthenic patient aims at reviewing the severity of the patient’s myasthenic condition and the treatment control. Specific consideration should be attributed to voluntary and respiratory muscle strength. During labor, epidural analgesia should be used to diminish pain. The use of narcotic/neuromuscular blocking agents should be avoided. Local anesthetic agents might be avoided (as much as possible), as these can block the neuromuscular transmission. Non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking drugs should be avoided. Sedatives and opioids need to be avoided, as these may accelerate the respiratory depression(12). The potential for respiratory alterations in these patients obliges the anesthesiologist to be up-to-dated with the underlying disease stage, as well as the impact of anesthetic and non-anesthetic drugs on patients with myasthenia gravis. Inhaled anesthetics also exert muscle relaxation, but in the case of myasthenic ill, it acquires a special sensitivity. Sevoflurane and isoflurane impair the neuromuscular function, with a sensitivity close to 90% in myasthenic patients. It seems that the anesthetic opioids detected in the plasma concentrations of these patients do not weaken the neuromuscular transmission(13). Also, the most tolerated short-acting intravenous anesthetics, such as propofol, do not affect neuromuscular function.

Neonatal considerations

Regarding the review of some neonatological features of myasthenia gravis, attention should first be paid to the mother-to-child myasthenia gravis antibodies transfer. Autoantibodies per se do not seem to give infertility. The placental transfer of maternal IgG antibodies to the fetus is a primordial mechanism that grant protection to the neonate while his/her humoral response is ineffective. IgG is the only antibody class that significantly crosses the human placenta(14). In nearly all patients, the antibodies bind to acetylcholine receptors (AChR), but on the other hand, it was shown that other incriminated target is the muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK) and lipoprotein-related peptide 4 (LRP4)(15). Around 10% of the babies of myasthenic mothers have a transient muscle weakness. This is due to antibodies against AChR or MuSK that are carried from the mother’s circulation, across placenta, to the fetus. In the neonate, these antibodies may bind to their respective antigens and induce muscle weakness, which nearly always appear in the course of the first 24 hours after birth. As mother’s IgG antibodies are impaired in the baby and gradually disappear, the muscle weakness improves, and the normal function recover(16). The weakness usually lasts for up to 4 weeks, but is most noticeable during the first week.

The characteristic symptoms are slight general hypotonia and poor sucking due to reduced muscle tonus. Dysphagia and a weak cry are other symptoms noticed in neonates. Insufficient respiration, meconium aspiration and pneumonia are not so often reported, but these make the neonatal ward monitoring necessary for those infants, and lately difficulty breast feeding by ineffective sucking. Breast feeding is very important in the development and well-being of every infant, therefore we will point out a relevant aspect from this point of view. Fetal dysphagia result in association to polyhydramnios in some pediatric neonatal disorders, which is very important to detect, observe and relate to possible swallowing difficulties.

Feeding problems installed at birth, with a neonatal onset, are often related to weak/poor sucking. In most neuromuscular diseases, excepting spinal muscular atrophy, the triggering and timing of swallowing in the bulbar region appear normal(17), therefore dysphagia is mainly associated to weakness of the oral muscles rather than to incoordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing. At the beginning, neonates suckle from the breast (or bottle), but after about 3 months, the brainstem reflexes – for instance, the sucking reflex – disappear, and by about 6 months the infants begin eating foods of diverse consistencies. The oral anatomy modifies as a result of the advance of the oral cavity and the downgrade of laryngeal structures. Between 6 and 12 months, infants’ reflexes for chew and swallow appears, so the infants will start to learn to eat pureed or solid food(18), which necessitate better strength of the oral muscles. For example, the muscular weakness at the level of orbicularis of the lips leads indirectly to reduced pharyngeal pressure, leading to post-swallow residue and indirect aspiration (the risk to aspirate the regurgitated material), thus the careful introduction to small quantities of liquids and food might be taken in consideration(19). Without going into detail about congenital myasthenic syndromes, we have chosen only to enumerate them, their exposure broadly being the subject of strict concerns of neonatologists. The types of pediatric myasthenic syndromes:

1. Congenital myasthenia gravis.

2. Transient neonatal myasthenia gravis.

3. Juvenile autoimmune myasthenia gravis.

4. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (as a persistent sequela in child).

Conclusions

We hope that this article will support, first and foremost, the neurologists and gynecologists who face the great challenges that this multifaceted disease brings to our attention. All babies by myasthenic mothers should be observed and monitored in the hospital for at least 72 hours. The obstetrical and neurological follow-up during pregnancy should be an important prerequisite in order to prevent unpleasant events. From the long experience of our clinic, myasthenic women are recommended to get pregnant 3-5 years after thymectomy, when the disease stabilizes. Before pregnancy, patients undergo a complete biological and infectious assessment to avoid antibiotic treatment in the first semester of pregnancy. During pregnancy until the seventh month, it is recommended to continue the maintenance treatment with Medrol® and Mestinon® until another neurological reevaluation, by increasing the dose of Medrol® until they return to control after birth. All these steps are necessary in order to avoid the aggravation of myasthenia in the last trimester of pregnancy, during pregnancy and after that. During pregnancy, myasthenic crises set in and manifest in the first trimester of pregnancy, and we encountered situations in which patients had to be curetted in the ICU department, a life-saving workforce. In our activity, myasthenic crises have also been reported after birth, borderline situations in which plasmapheresis has proven to be effective and life-saving for both mother and newborn. The neonatal myasthenic phenomena (transient neonatal myasthenia) improved 3-4 weeks after the Mestinon® administration.

Bibliografie

-

1. Gilhus NE, Owe JF, Hoff JM, Romi F, Skeie GO, Aarli JA. Myasthenia gravis: a review of available treatment approaches. Autoimmune Dis. 2011; 2011:847393.

-

2. Ferrero S, Pretta S, Nicoletti A, Petrera P, Ragni N. Myasthenia gravis: management issues during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;121(2):129–38.

-

3. Buckley C, Douek D, Newsom-Davis J, Vincent A, Willcox N. Mature, long-lived CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are generated by the thymoma in myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(1):64–72.

-

4. Hoff JM, Daltveit AK, Gilhus NE. Myasthenia gravis in pregnancy and birth: Identifying risk factors, optimising care. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:38–43.

-

5. Chaudhry SA, Vignarajah B, Koren G. Myasthenia gravis during pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2012 Dec;58(12):1346–1349.

-

6. Ferrero S, Pretta S, Nicoletti A, Petrera P, Ragni N. Myasthenia gravis: management issues during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;121(2):129–38.

-

7. Berlit S, Tuschy B, Spaich S, Sütterlin M, Schaffelder R. Myasthenia gravis in pregnancy: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:736024.

-

8. Smulowitz PB, Zeller J, Sanchez LD, et al. Myasthenia gravis: Lessons for the emergency physician. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12(6):324–6.

-

9. Batocchi AP, Majolini L, Evoli A, et al. Course and treatment of myasthenia gravis during pregnancy. Neurology. 1999;52(3):447–52.

-

10. Varner M. Myasthenia gravis and pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;56(2):372–81.

-

11. Djelmis J, Sostarko M, Mayer D, Ivanisevic M. Myasthenia gravis in pregnancy: Report on 69 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;104:21– 25.

-

12. Sander DB, Wolfe GI, Benatar M, Evli A, Gilhus NE, Illa I, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2016;87:419–25.

-

13. O’Flaherty D, Pennant JH, Rao K, et al. Total intravenous anesthesia with propofol for transsternal thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. J Clin Anesth. 1992;4:241.

-

14. Palmeira P, Quinello C, Silveira-Lessa AL, Zago CA, Carneiro-Sampaio M. IgG Placental Transfer in Healthy and Pathological Pregnancies. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:985646.

-

15. Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1023–36.

-

16. Gilhus NE. Myasthenia Gravis Can Have Consequences for Pregnancy and the Developing Child. Front Neurol. 2020 Jun 12;11:554.

-

17. Lunn MR, Wang CH. Spinal muscular atrophy. Lancet. 2008 Jun 21;371(9630):2120-33.

-

18. Delaney AL, Arvedson JC. Development of swallowing and feeding: Prenatal through first year of life. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2008;14(2):105–117.

-

19. Matsuo K, Palmer JB. Anatomy and physiology of feeding and swallowing: Normal and abnormal. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008;19(4):691–707.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Tipuri actuale de naştere şi impactul lor asupra mamei şi fătului

În urma evoluţiei modalităţii de naştere, am constatat, potrivit unui studiu observaţional efectuat în clinica noastră în perioada 2017-2021, o ten...

Rezultatele obstetricale şi neonatale ale sarcinilor complicate de infecţia cu SARS-CoV-2

Pandemia de COVID-19 are un impact fără precedent. Femeile gravide fac parte din populaţia vulnerabilă, iar amploarea consecinţelor infecţiei cu SA...

Valoarea predictivă a indicilor Doppler ai arterei uterine la 11-14 săptămâni pentru complicaţiile hipertensive ale sarcinii

Introducere. Complicaţiile hipertensive ale sarcinii pot duce adesea la situaţii grave, chiar cu potenţial letal pentru mamă şi făt. Ecografia Dopp...

Accidentul vascular cerebral perinatal – coşmarul neurodezvoltării fetale

Accidentul vascular cerebral perinatal este un sindrom polimorf cauzat de o leziune vasculară cerebrală. Apare între 20 de săptămâni de gestaţie şi...