Provocările diagnosticului diferenţial dintre pseudomixomul peritoneal şi neoplazia ovariană primară. Prezentare de caz şi review al literaturii

The challenges of differential diagnosis between pseudomyxoma peritonei and primary ovarian neoplasia. Case presentation and literature review

Abstract

Pseudomyxoma peritonei originates from primary mucinous neoplasms of the appendix or from different sites, especially the ovary. The specialized literature emphasizes the possibility of the existence of synchronous primary mucinous tumors of the ovary and appendix involved in the disease’s onset. If untreated, the prognosis of the patients diagnosed with pseudomyxoma peritonei is fatal, due to the compression and blockage of the digestive tract. Ascites associates a poor prognosis through the characteristic pharmacoresistance, tumor cells in this context presenting genomic changes of acquired resistance across the whole genome. We report the case of a 61-year-old woman with massive ascites and pleurisy and atypical laboratory and intraoperative aspect, respectively peritoneal carcinomatosis, with infracentimetric disseminations on the epiploon, mesentery and parietal peritoneum. Also, a tumoral pelvic block which included the uterus, the ovaries, the sigmoid colon and ileal loops was detected. The extraabdominal spread of pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome has a rare occurrence, with only few reports in literature. The differential diagnosis of primary tumor should be well established, because the misdiagnosis of a metastatic mucinous ovarian tumor as a primary neoplasia may adversely affect the surgical management, the complementary treatment and the prognosis.Keywords

pseudomixoma peritoneiovarian neoplasiachylous ascitesRezumat

Pseudomixomul peritoneal îşi are originea, în majoritatea cazurilor, în neoplasmele mucinoase primare ale apendicelui sau în alte structuri, în special în ovar. Literatura de specialitate subliniază posibilitatea existenţei tumorilor mucinoase primare sincrone ale ovarului şi apendicelui implicate în debutul bolii. Dacă nu este tratat, prognosticul pacienţilor diagnosticaţi cu pseudomixom peritoneal este fatal, având ca mecanism principal ocluziile tractului digestiv. Ascita reprezintă un element de prognostic rezervat, prin farmacorezistenţa caracteristică, celulele tumorale prezentând, în acest context, modificări genomice ale rezistenţei dobândite prezente în întregul genom. Raportăm cazul unei paciente în vârstă de 61 de ani, cu ascită masivă şi pleurezie şi cu aspecte atipice atât paraclinic, cât şi intraoperatoriu, respectiv carcinomatoză peritoneală, cu diseminări infracentimetrice epiploneale, la nivelul mezourilor, cât şi al peritoneului parietal. De asemenea, a fost remarcat un bloc pelvian tumoral care a inclus uterul, ovarele, colonul sigmoid şi ansele ileale. Răspândirea extraabdominală a sindromului pseudomixomului peritoneal este rară, cu numai câteva raportări în literatură. Diagnosticul diferenţial al tumorii primare ar trebui să fie clar stabilit, deoarece diagnosticul greşit al unei tumori ovariene mucinoase metastatice ca neoplazie primară poate afecta negativ managementul chirurgical, tratamentul complementar şi prognosticul.Cuvinte Cheie

pseudomixom peritonealneoplazie ovarianăascită chiloasăIntroduction

Pseudomyxoma peritonei, or gelatinous disease of the peritoneum, as Pean described it in 1871(1), is a rare condition estimated to occur in 1 to 2 individuals per million(2,3). More than that, only 45 cases were reported until 2018 in the English literature(2,4). It usually originates from primary mucinous neoplasms of the appendix (80% of the reported cases) or it arises from different sites, especially the ovary, with the peculiarity that primary ovarian mucinous adenocarcinomas presenting as pseudomyxoma peritonei were described as low-grade tumors in the majority of cases(2,5). In addition to that, the specialized literature emphasizes the possibility of the existence of synchronous primary mucinous tumors of the ovary and appendix involved in the disease’s onset, but this possibility represents the subject of an important debate(5,6). It is stipulated that this disease affects most frequently women with the age between 50 and 70 years old(2).

The clinical syndrome’s course is characterized by the production of mucine, leading to abundant gelatinous ascites, and not by intracellular mucin accumulation in tumor cells. Also, the rupture or leakage of a mucinous neoplasm within the abdomen was involved in the onset of the disease. It is described as a locoregional disease, with a high propensity for spread to peritoneal surfaces, but almost no lymphatic or hematogenous metastases(7,8). If untreated, the prognosis of the patients diagnosed with pseudomyxoma peritonei is fatal, due to the compression and blockage of the digestive tract(2).

Ovarian carcinoma remains one of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity from the field of gynecologic-related malignancies(9), and the optimal treatment of these cases can represent a real challenge for the clinician. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) estimates that two out of three cases of ovarian carcinoma are diagnosed in an advanced stage of the disease(9), this being due to the natural biology of the disease and also to the inexistent efficient screening methods.

Regarding the mucinous ovarian carcinoma, it is estimated nowadays to have an incidence of only 3% because of the recognition of clinical and pathological features of benign mucinous tumors from the invasive ones and between primary and metastatic tumors. The mucinous ovarian carcinoma is described as having a distinct natural history and molecular profile and as not being associated with the known risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer, excepting tobacco smoking. Eighty percent of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary are metastatic, thus the recognition of immunochemistry profile is essential for the diagnosis and to predict an accurate prognosis(10). It is revealed that mucinous ovarian carcinoma of intestinal type is associated with an increased level of CA 19.9, with diffusely negative CA 125 and with diffusely positive or focally negative CEA(5).

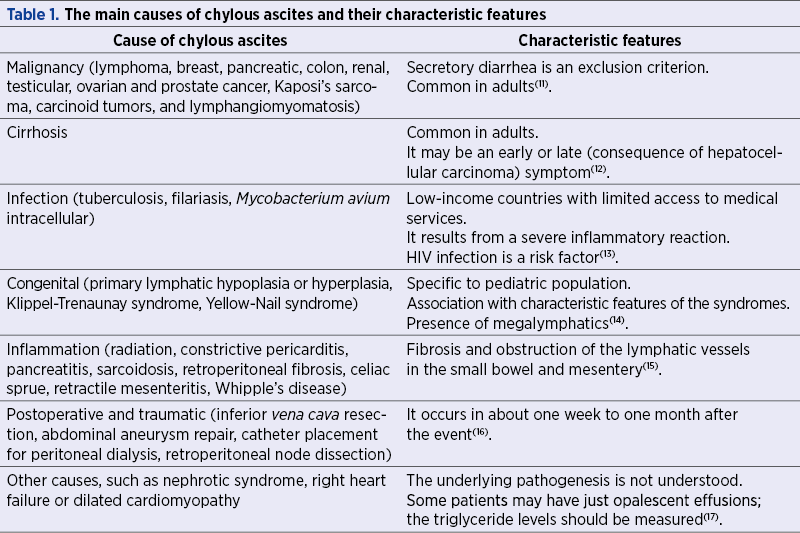

Severe ascites is a significant indicator of advanced ovarian cancer, but the mechanisms that are responsible for the imbalance existing between peritoneal vascular leakage and lymphatic drainage are still not fully understood. Chylous ascites is the accumulation of peritoneal fluid, rich in triglycerides and with a milk-like aspect, as a response to the disruption of the lymphatic system after a traumatic injury or obstruction from malignant or benign causes. Table 1 summarizes the main causes and the differential diagnosis of chylous ascites.

In developing countries, tuberculosis is the main etiological factor; however, in developed states, cirrhosis and malignancies account for about two thirds of the cases(11). There is no reported incidence of chylous ascites in Romania, but from the data presented in the specialized literature, this complication is found in 1 out of 20,000 admissions, with an estimated increasing incidence regarding the higher incidence of aggressive cardiothoracic and abdominal surgeries and with prolonged survival rates of cancer patients(11). However, the mechanism of formation of chylous ascites in pseudomyxoma peritonei consists in the implantation of mucine of the peritoneal surfaces(1,2). Several theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of ascites in pseudomyxoma peritonei, including multifocal neoplasia of the peritoneum, ovaries, and appendix(18,19), mucinous metaplasia of the peritoneum(19,20), and metastasis or leakage from a primary mucinous neoplasm of the ovary or appendix(21,22).

Ascites associates a poor prognosis through the characteristic pharmacoresistance, tumor cells in this context presenting genomic changes of acquired resistance across the whole genome(23). Although the effective palliation of malignant ascites is difficult and challenging, the elimination of the fluid will firstly improve the patient’s quality of life and can prolong survival through a better response on targeted therapeutics procedures(24).

Case report

We report the case of a 61-year-old woman, known with psoriasis, who was admitted in the Department of Gastroenterology of the Bucharest University Emergency Hospital, accusing abdominal distention, dyspnea and weight loss, with onset of about two months. The clinical examination revealed psoriatic lesions on the upper limbs, diminished vesicular murmur in the lower third of right hemithorax, increased respiratory rate (26 breaths/minute) and a distended, in tension, painless spontaneously and on palpation abdomen.

The laboratory findings showed elevated values of tumoral markers (CA 125=406.3 U/ml, CEA=5.13 ng/ml), hepatic cytolysis (ALT=125 U/L, AST=70 U/L), hepatic cholestasis (GGT=296 U/L), mild hypoalbuminemia (3.1 mg/dl), mild hyperkaliemia (5.5 mmol/L) and negative hepatic viral markers. Also, a SARS-COV-2 rt-PCR test was performed, given the current epidemiological context.

A pulmonary radiography was performed which showed pulmonary hyperinflation, accentuation of the bilateral basal peribronhovascular interstitial pattern, and small right pleural effusion. Also, the abdominal radiography showed no hydroaeric levels.

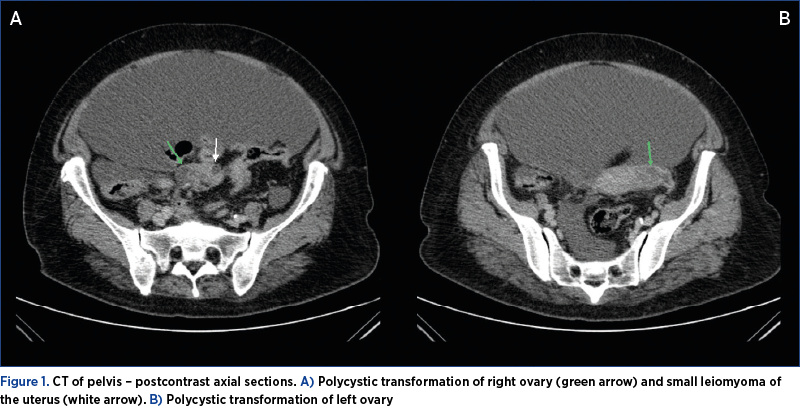

The transvaginal ultrasound revealed massive ascites, a uterus with the dimensions of 72/25/51 mm, with nonhomogeneous diffuse myometrium with some calcifications, and small ovaries without cystic tumors. A computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, which detected polycystic ovarian measuring 26 mm on the right side and 33 mm on the left side (Figure 1).

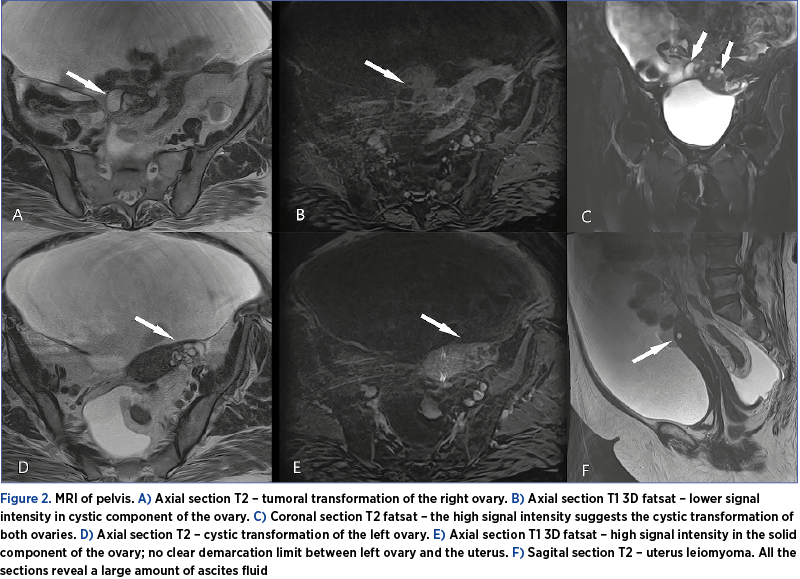

On the other hand, the MRI of the abdomen and pelvis showed bilateral adnexal expansive processes, with heterogeneous, mixed cystic-solid consistency, with polycyclic contour, forming a common block with the uterus and measuring 36/40 mm on the right side and 43/27 mm on the left side (Figure 2).

A paracentesis was performed, with the evacuation of 5 liters of ascites fluid (characterized by the laboratory findings as exudate), and the diuretic treatment was initiated.

The patient was referred to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Bucharest University Emergency Hospital for an interdisciplinary consultation. When reevaluating, the patient showed no relief of symptoms, with the persistence of abdominal pain and dyspnea. New laboratory findings showed an increased level of CA 19.9 (86.8 U/ml). The pulmonary radiography revealed bilateral pleural effusion, with a tendency to imprisonment. A right bundle branch block and left axial deviation were discovered during a cardiological evaluation, therefore, additional to the diuretic treatment, a selective beta-blocker treatment was initiated.

Given the patient’s low oxygen saturation (SaO2 94%), an ultrasound-guided thoracentesis was performed, with the evacuation of 400 ml of pleural fluid, which was sent for cytologic analysis.

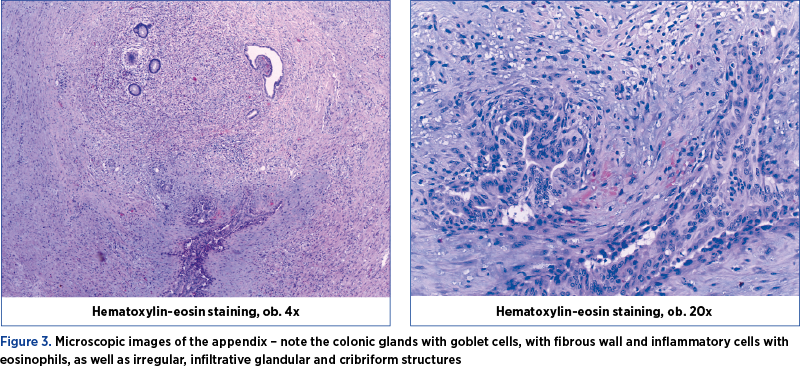

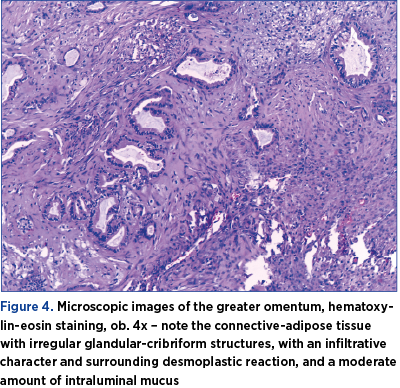

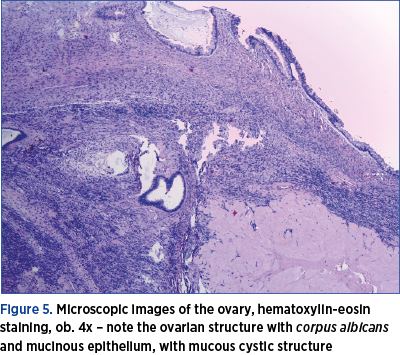

Under general anesthesia, an exploratory laparotomy was performed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of gynecologists and general surgeons. We detected peritoneal carcinomatosis, with infracentimetric disseminations on the epiploon mesentery and parietal peritoneum; a tumoral pelvic block which included the uterus, ovaries, sigmoid colon and ileal loops; the ovaries were measuring 3/2/1 cm on the right side and 3/2/2 cm on the left side, with bilateral small cysts and without capsular breakage; also, a 1.5-cm diameter secondary dissemination was detected on mesentery’s root. During surgery, 10 liters of ascites fluid with milky appearance were extracted, from which samples for cytology and bacterial culture were collected. Tumor cytoreduction through total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy, peritoneal biopsy and appendectomy (the histopathological extemporaneous examination showed mucinous adenocarcinoma) was performed. The final histopathological result described pseudomyxoma peritonei and metastases of mucinous adenocarcinoma in the ovary and appendix, without the possibility to determine the origin of the primary tumor (Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6). Thus, immunohistochemistry (IHC) test was indicated.

The postoperative evolution was favorable, with the relief of the proeminent symptoms. However, the peritoneal drainage was maintained for 7 days, with the evacuation of approximately 6 liters of ascites fluid during this period, and the patient’s oxygen saturation was in a progressive decline (up to 90%). A treatment with Miofilin® and hydrocortisone hemisuccinate was initiated. The patient was discharged after 12 days of hospitalization and was guided to the oncology department for specialized treatment after receiving the IHC results.

Discussion

Pseudomyxoma peritonei defines a very rare condition caused by primary mucinous tumors that arise from different sites, usually the appendix or ovary(5,24). The pathology involves a hypersecretion of mucine which determines the rupture of the tumor and the dissemination of the mucus in the abdominal cavity(25). The peritoneal implantation of mucine leads to abundant chylous ascites, which determines multiple recurrences and progressive fibrous adhesions, leading to fatal intestinal obstruction(5,26).

There are no pathognomonic signs to diagnose pseudomyxoma peritonei, as this very rare entity can cover various symptoms, from a simple abdominal pain to subocclusive syndrome. The radiographic features show loculated collections of fluid, along the peritoneal surfaces. The appearance of coated abdominal organs and omental caking is frequent. The CT scan evaluation reveals low attenuation fluid throughout intraperitoneal areas, omentum or mesentery, while the MRI characteristics of the fluid include a low signal in T1 and high signal in T2(27,28).

Tumor markers (CEA, CA 19.9, CA 125) are not useful for the diagnosis of the disease(2). In our case, all the tumor makers were abnormal. CA 125, a glycoprotein encoded by MUC16 gene on chromosome 19, has been reported to increase in only 12% of ovarian mucinous carcinomas. In our case, the incresead level of this marker can be explained by the presence of ascites fluid(29). Regarding CA 19.9, a monosialoganglioside secreted by mucinous tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, a limited number of studies sustained that this tumoral marker can predict a primary mucinous ovarian tumor, although in our case its level was slightly increased(30). Considering a study performed by Numella et al. in 2018, of all the tumoral markers analyzed in our case report, only CEA can be exploited to target specialized therapy(31).

Extraabdominal spread of pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome has a rare occurrence (5.4%), with few reports in literature. The pleural extension of mucinous tumor in this syndrome was described before cytoreductive surgery in only 17% of these cases(32). The pleural fluid, besides the ascending of the diaphragm, was associated in our case with dyspnea and a low saturation in oxygen.

The main option in the management, when ovarian neoplastic ascites is highly suspected, is cytoreductive surgery, which in association with chemotherapy has a response rate of up to 70%(33). Cytoreductive intervention involves hysterectomy, adnexectomy, pelvic and paraaortic lymph node dissection, omentectomy, and excision of all macroscopically visible secondary determinations.

Appendectomy is routinely recommended in mucinous carcinoma. In a group of 269 patients operated for ovarian mucinous carcinoma, in which 172 appendectomies were performed, Rosendhal et al. identified micrometastases of mucinous carcinoma on appendix with normal macroscopic appearance. There is always a risk of micrometastasis, therefore routine appendectomy is recommended, especially since this interventional step does not increase the postoperative morbidity and may clarify the difficulties of differential diagnosis regarding the origin of the initial tumor in mucinous carcinoma(34).

The standard therapy for refractory or advanced ascites that have not been able to benefit from surgery consists of repeated paracentesis. The method is minimally invasive and can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Another surgical approach is the radical excision of the peritoneum, which is associated with intraperitoneal administration of chemotherapeutics (cisplatin or paclitaxel) in conditions of hyperthermia. However, this method has not been shown to be effective in mucinous ovarian carcinoma(35-38).

The diuretic treatment has not been shown to be useful in neoplastic ascites and is less effective compared to paracentesis(32). Spironolactone 100-200 mg/day and furosemide 40-80 mg/day may be administered, but their use is recommended for limited periods, as they may induce hypovolemia, hypotension, renal failure and increase the risk of thromboembolic events in chemotherapy(39).

A new approach in the treatment of neoplastic ascites is monoclonal therapy that addresses directly some of the etiopathogenic factors of ascites, respectively neoangiogenesis. In 2016, bevacizumab (FDA-approved for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer) was shown to be effective in relapsed disease associated with ascites(32,40). The most common complications of monoclonal treatment are thrombocytopenia and neutropenia(40).

Cytoreductive surgery is the gold standard surgical intervention. However, the recurrence rate is high due to the impossibility to remove all the peritoneum surface(32). In our case, we observed a very accelerated rhythm of formation of ascites, despite the extensive cytoreductive surgery.

Conclusions

Pseudomyxoma peritonei is a very rare disease, described by an indolent and progressive growth pattern, whose diagnosis relies on the histopathological and immunochemistry findings. The differential diagnosis of primary tumor should be well established, because the misdiagnosis of a metastatic mucinous ovarian tumor as a primary neoplasia may adversely affect the surgical management, the complementary treatment and the prognosis. Comparative studies on quality of life and disease progression, between monoclonal therapy and paracentesis associated or not with intraperitoneal chemotherapy as treatment options for refractory ascites, show a better quality of life and longer remission intervals of neoplastic ascites in favor of monoclonal therapies.

Bibliografie

-

1. Zeraidi N, Chahtane A, Lakhdar A, Khabouz S, Berrada R, Rhrab B, et al. La maladie gélatineuse du péritoine à propos d’un cas. Clinique. 1996;1(2):3.

-

2. Ziadeh H, Clerc J, Brieux D, Van-Nieuwenhuyse A, Lambert JR. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei with Metastatic Ovarian Tumor in a 28-Years-Old Patient: A Case Report with Review of the Literature. World J Surg Surgical Res. 2018;1:1055.

-

3. Diaz-Zorrilla C, Ramos-De la Medina A, Grube-Pagola P, de Velasco ARG. Pseudomyxoma extraperitonei: a rare presentation of a rare tumour. Case Reports. 2013; bcr2012007702.

-

4. Smeenk RM, Van Velthuysen MLF, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FAN. Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a population based study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO). 2008;34(2):196-201.

-

5. Suh DS, Song YJ, Kwon BS, Lee S, Lee NK, Choi KU, Kim KH. An unusual case of pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with synchronous primary mucinous tumors of the ovary and appendix: a case report. Oncology Letters. 2017;13(6):4813-4817.

-

6. Guerrieri C, Frånlund B, Fristedt S, Gillooley JF, Boeryd B. Mucinous tumors of the vermiform appendix and ovary, and pseudomyxoma peritonei: Histogenetic implications of cytokeratin 7 expression. Hum Pathol. 1997;28(9):1039–1045.

-

7. Smeenk RM, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33(2):138–145.

-

8. Winder T, Lenz HJ. Mucinous adenocarcinomas with intra-abdominal dissemination: a review of current therapy. The Oncologist. 2010;15(8):836-844.

-

9. Stănescu AD, Pleş L, Edu A, Olaru GO, Comănescu AC, Potecă AG, Comănescu MV. Different patterns of heterogeneity in ovarian carcinoma. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 2015;56(4):1357-1363.

-

10. Babaier A, Ghatage P. Mucinous cancer of the ovary: overview and current status. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Jan 19;10(1):52.

-

11. Aalami O, Allen DB, Organ CH. Chylous ascites: A collective review. Surgery. 2000;128(5):761–78.

-

12. Sultan S, Pauwels A, Poupon R, Levy VG. Chylous ascites in cirrhosis. Retrospective study of 20 cases. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14(11):842–7.

-

13. Keavney A, Karasik MS, Farber HW. Successful treatment of chylous ascites secondary to Mycobacterium avium complex in a patient with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1689–90.

-

14. Cohen MM. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2000;93:171–5.

-

15. Gilkeson GS, Allen NB. Retroperitoneal fibrosis. A true connective tissue disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1996;22(1):23–38.

-

16. Edoute Y, Nagachandran P, Assalia A, Ben-Ami H. Transient chylous ascites following a distal splenorenal shunt. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47(32):531–2.

-

17. Kato A, Kohno S, Ohtake T, et al. Chylous ascites in an adult patient with nephritic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy. Nephron. 2001;89(3):361–2.

-

18. Jackson SL, Fleming RA, Loggie BW, Geisinger KR. Gelatinous ascites: a cytohistologic study of pseudomyxoma peritonei in 67 patients. Modern Pathology. 2001;14(7):664-671.

-

19. Albu DF, Albu CC, Văduva CC, Niculescu M, Edu A. Diagnosis problems in a case of ovarian tumor – case presentation. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 2016;57(4):1437-1442.

-

20. Sandenbergh HA, Woodruff JD. Histogenesis of pseudo-myxoma peritonei: review of 9 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49(3):339–345.

-

21. Campbell JS, Low P, Ferguson JP, Krongold I, Kemeny T, Mitton DM, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei et ovarii with occult neoplasms of the appendix. Obstet Gynecol. 1973;42(6):897–902.

-

22. Patch AM, Christie EL, Etemadmoghadam D, Garsed DW, George J, Fereday S, et al. Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature. 2015;521(7553):489-94.

-

23. Albu DF, Albu CC, Goganau AM, Albu SD, Mogoanţă L, Edu A, Ditescu D, Văduva, CC. Borderline Brenner tumors associated with ovarian cyst – case presentation. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 2016;57(2):893-898.

-

24. Chira RI, Nistor-Ciurba CC, Mociran A, Mircea PA. Appendicular mucinous adenocarcinoma associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei, a rare and difficult imaging diagnosis. Med Ultrason. 2016;18(2):257–259.

-

25. Fairise A, Barbary C, Derelle A L, Tissier S, Granger P, Marchal F, et al. Mucocele of the appendix and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Journal de Radiologie - Paris. 2008;89(6):751-62.

-

26. Baratti D, Kusamura S, Nonaka D, Cabras AD, Laterza B, Deraco M. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: Biological features are the dominant prognostic determinants after complete cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2009;249(2):243–249.

-

27. Bartlett DJ, Thacker PG, Grotz TE, Graham RP, Fletcher JG, et al. Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms: classification, imaging, and HIPEC. Abdominal Radiology. 2019;44(5):1686–1702.

-

28. Buy JN, Malbec L, Ghossain MA, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Eur J Radiol. 1989;9(2):115-8.

-

29. Choi JH, Sohn GS, Chay DB, Cho HB, Kim JH. Preoperative serum levels of cancer antigen 125 and carcinoembryonic antigen ratio can improve differentiation between mucinous ovarian carcinoma and other epithelial ovarian carcinomas. Obstetrics & Gynecology Science. 2018;61(3):344-351.

-

30. Kelly PJ, Archbold P, Price JH, Cardwell C, McCluggage WG. Serum CA19.9 levels are commonly elevated in primary ovarian mucinous tumours but cannot be used to predict the histological subtype. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2010;63(2):169-173.

-

31. Nummela P, Leinonen H, Järvinen P, Thiel A, Järvinen H, Lepistö A, Ristimäki A. Expression of CEA, CA19-9, CA125, and EpCAM in pseudomyxoma peritonei. Human Pathology. 2016 Aug;54:47-54.

-

32. Pestieau S R, Esquivel J, Sugarbaker PH. Pleural extension of mucinous tumor in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2000;7(3):199-203.

-

33. Pleş L, Sima RM, Burnei A, Albu DF, Bujor MA, Conci S, Teodorescu V, Edu A. The experience of our Clinic in laparoscopy for adnexal masses and the correlation between ultrasound findings and pathological results. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology. 2016;57(4):1337-1341.

-

34. Živadinović R, Petrić A, Krtinić D, Pop-Trajković Dinić S, Živadinović B. Ascitic Fluid in Ovarian Carcinoma – From Pathophysiology to the Treatment. 2017 Nov; DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.70476

-

35. Mackey JR, Venner PM. Malignant ascites: Demographics, therapeutic efficacy and predictors of survival. Canadian Journal of Oncology. 1996;6(2):474-480

-

36. Rosendahl M, Haueberg Oester LA, Høgdall CK. The Importance of Appendectomy in Surgery for Mucinous Adenocarcinoma of the Ovary. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(3):430-436.

-

37. Chung M, Kozuch P. Treatment of malignant ascites. Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 2008;9(2-3):215-233.

-

38. Cîrstoiu MM, Sajin M, Secară DC, Munteanu O, Cîrstoiu FC. Giant ovarian mucinous cystadenoma with borderline areas: a case report. RJME. 2014;55(4):1443-1447.

-

39. Kaufmann M, Schmid H, Raeth U, Grischke EM, Kempeni J, Schlick E, et al. Therapy of ascites with tumor necrosis factor in ovarian cancer. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1990;50(9):678-682.

-

40. Sharma S, Walsh D. Management of symptomatic malignant ascites with diuretics: Two case reports and a review of the literature. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1995;10(3):237-242.