CANCERUL DE CANAL ANAL

Cancerul de canal anal - aspecte legate de diagnostic și tratament

Anal canal cancer diagnosis and treatment aspects

Abstract

Anal cancer represents a rare neoplasia, accounting for approximately 1.5% of all digestive cancers, but remains an important concern due to its association to sexually-transmitted infections and still dismal prognosis. This review focuses on the main diagnostic and treatment aspects concerning anal canal cancer. Anal cancer incidence has been increasing in the last years, probably due to the rise in the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, such as HPV and HIV infections. Although many risk factors have been associated to anal cancer (HPV, HIV infection, immunocompromised status, tobacco smoking), anal cancer biology is only partly understood. The most frequent histopathologic type of anal canal cancer is represented by squamous-cell carcinoma (80% of all anal canal cancers). Anal canal cancer should be distinguished from anal margin cancer, which is of better prognosis. Anal cancer diagnosis is usually delayed, due to its resemblance to benign perianal pathology that justifies the need for a better screening. Anal canal carcinoma therapeutic management has witnessed a major shift in time from a radical surgical (abdominoperineal resection) to multimodal approach. Nowadays, the standard treatment of anal carcinoma is represented by radiochemotherapy that is an effective therapy although can associate an important toxicity. Surgical treatment is reserved only to very small anal lesions and especially to residual disease or tumor recurrences after primary therapy, representing a salvage therapy (abdominoperineal rectal amputation) for these cases. Although approximately 10-30% of the patients present with inguinal lymph node metastases at initial diagnosis, prophylactic inguinal lymphadenopathy is not recommended, due to its associated complications and better response to radiotherapy. Inguinal lymphadenectomy is only indicated for voluminous lymphadenopathy blocks and inguinal lymph node metastases appeared after radiochemotherapy.Keywords

anal cancerrisk factorsdiagnostic treatmentRezumat

Cancerul anal reprezintă o neoplazie rară, constituind aproximativ 1,5% din totalitatea cancerelor digestive, dar rămâne o preocupare deosebită din cauza asocierii sale cu infecțiile cu transmitere sexuală și prognosticului asociat încă nesatisfăcător. Acest review vizează surprinderea principalelor aspecte de diagnostic și tratament privind cancerul de canal anal. Incidența cancerului anal a suferit o creștere în ultimii ani, probabil din cauza accentuării răspândirii infecțiilor cu transmitere sexuală, precum infecția cu HPV și HIV. Deși mulți factori de risc au fost asociați cu cancerul anal (infecția cu HPV, HIV, statusul imunocompromis, fumatul), biologia cancerului anal rămâne doar parțial înțeleasă. Cel mai frecvent subtip histopatologic de cancer de canal anal este reprezentat de carcinomul scuamos (80% din totalitatea cancerelor de canal anal). Cancerul de canal anal ar trebui diferențiat de cancerul de margine anală, care asociază un prognostic mai bun. Diagnosticul cancerului de canal anal este în general întârziat, din cauza asemănării sale cu patologia perianală benignă, ceea ce justifică necesitatea unui screening îmbunătățit. Managementul terapeutic al carcinomului anal a înregistrat o modificare majoră în timp, de la o abordare chirurgicală radicală (amputația rectală abdominoperineală) la o terapie multimodală. Astăzi, tratamentul standard al cancerului anal este reprezentat de radio-chimioterapie, care reprezintă o terapie eficientă, deși poate asocia o toxicitate semnificativă. Tratamentul chirurgical e rezervat doar leziunilor anale foarte mici și în special bolii reziduale și recidivelor tumorale după terapia primară, pentru care reprezintă o terapie de salvare (amputația de rect abdominoperineală). Aproximativ 10-30% din pacienți prezintă la diagnosticarea inițială metastaze limfatice inghinale; totuși, limfadenectomia inghinală profilactică nu e recomandată, din cauza complicațiilor asociate și a răspunsului mai bun la radioterapie. Limfadenectomia inghinală e indicată doar pentru blocurile adenopatice inghinale voluminoase sau metastazelor ganglionare inghinale survenite după radio-chimioterapie.Cuvinte Cheie

cancer canal analfactori de riscdiagnostictratamentBackground

1. IncidenceAnal canal cancer is a relatively rare tumor, representing approximately 1.5% of all digestive cancers in the United States(1). It is approximately 20 to 30 times rarer than colon cancer, but its annual incidence is increasing, reaching up to 4000 cases, with a female predominance(2). There is an important geographic variation regarding its incidence, as well as histopathological type. Therefore, in the United States, up to 80% of anal cancers are represented by squamous-cell carcinomas, while in Japan adenocarcinomas account for the same percent(3). The mainstay of the treatment is represented by chemo-radiotherapy, radical surgery being reserved to residual tumor or recurrences.

2. Histopathology

Depending on the lining epithelium, anal canal is divided into three regions:

- colorectal zone: located proximally and containg columnar epithelium;

- transitional zone: spread over a distance that varies between 0 and 12 mm that contains a pseudostratified type of epithelium resembling the urothelial one. A transformation zone is unanimously accepted in uterine cancer. Some authors propose a rectal “transformation” zone in which squamous cell metaplasia covers the normal cylindrical epithelium and the upper extension can sometimes reach 10 cm. This region of metaplasia is extremely susceptible to HPV action(4);

- squamous zone: contains a non-keratinized epithelium, without hair follicles.

Concerning anal margin neoplasia, these are represented by:

- Bowen disease (in situ squamous-cell carcinoma);

- invasive squamous-cell carcinoma;

- Paget disease;

- basal cell carcinoma: an extremely rare tumor, approximately 20 cases having been reported in 20 years(28), that is of good prognostic.

- verrucous carcinoma: also known as Buschke-Lowenstein disease. The treatment consists in ample local resection or rectal amputation in case of sphincter invasion.

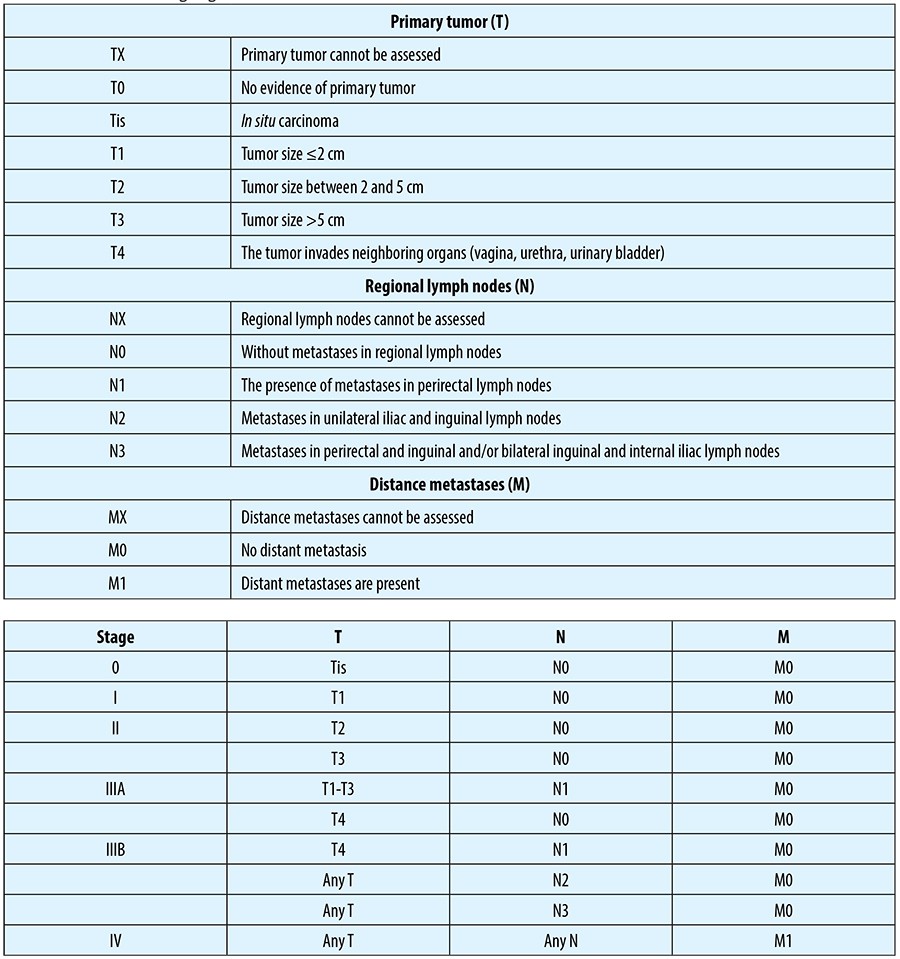

Anal cancer staging is based on tumor dimension, lymph node status and presence or absence of distance metastases.

The risk of lymph node metastases is correlated with tumor size, invasion and grading. Thus, based on a study conducted in 2003, lymph node metastatic rate in relation to T status has been the following: T1 - 0%; T2 - 8.5%; T3 - 29%; T4 - 35%(16). Approximately 10-30% of the patients present with inguinal metastases at initial diagnosis and another 10-22% develop them during the course of their disease(17).

Distance metastases can be found in 10-17% of the patients at the time of the diagnosis, liver, lung and bone metastases being the most frequent(18).

4. Risk factors

- Benign perianal pathology - perianal fissures and fistulas determine a chronic local inflammation that can lead to genetic alterations and have been incriminated as being etiologic factors. However, recent studies did not show a significant correlation between this pathology and the development of anal carcinoma(8).

- Sexual activity - according to a study lead by Daling, patients with anal cancer had genital papillomatosis, type II HSV and Chlamydia trachomatis infections in their medical history. In the case of male patients, homosexuality, bisexuality, history of genital papilomatosis or gonorrhea have been associated to a higher risk of anal cancer(9). Another study, published in 1997, adds to the risk factors, for females: history of gonorrhea, uterine cervix dysplasia, more than 10 sexual partners, anal sexual intercourse; for male patients: syphilis is another risk factor(10).

- HPV infection - it is the widest spread sexually transmitted infection in Europe(11). Anal HPV infection can be clinically inapparent or it may manifest as condyloma. Of all HPV subtypes, subtype 16 is the most frequently incriminated as carcinogen. In a study conducted in 1991, HPV has been found in 85% of anal cancer patients(12). Viral transmission is not influenced by the use of condoms as it is localized at the base of the penis and scrotum.

- Cigarette smoking - a study conducted in the early 1990s highlighted a relative risk of 1.9 for the patients that smoke 20 packs of cigarettes/ year and one of 5.2 for those smoking over 50 packs of cigarettes/year(13). Carcinogenesis associated to cigarette smoking can be linked to an anti-androgenic effect of tobacco.

- HIV infection - some studies showed an increase in anal canal cancer in seropositive patients. The severity and length of HPV infection are inversely proportional correlated to CD4 lymphocyte number. Immunocompromised patients, either due to HIV infection or to post-transplantation status or chemotherapy, have an increased risk of HPV infection and progression to squamous cell carcinoma(15).

Anatomy

Surgical anal canal spreads from ano-rectal ring (2 cm above the dentate line) to the external anal orifice. Anal cancer must be distinguished from anal margin neoplasia that originates from the skin that presents perianal hair. Some authors consider a 5 cm distance from the external anal orifice as the lateral limit(29). The correct classification of perianal neoplasia into the two mentioned categories is extremely important as those of anal margin are of better prognosis. Altogether, an erroneous classification could overestimate the role of radio-chemotherapy(30).Pectinate line represents an extremely important landmark for the vascularization and lymph node drainage. Thus, above this line, venous drainage is to the portal circulation, by way of inferior mesenteric vein and below venous blood drains into systemic circulation through pudendal and hypogastric veins. Above the pectinate line lymphatics drain into the inferior mesenteric, but also to hypogastric and obturatory lymph nodes, while below pectinate line-especially to inguinal lymph nodes, but also to femoral ones(31).

Diagnosis

Clinical examinationApproximately 20% of patients are asymptomatic, the remainder presenting with blood loss (the most frequent symptom), local pain, palpation of a tumor mass, rectal tenesmus, pruritus. Due to the resemblance to benign perianal pathology, the diagnosis is too often delayed.

Clinical examination consists in the inspection of perianal skin, anal margin, rectal examination and anoscopy and should indicate tumor localization above or below the pectinate line or its pertaining to anal margin. Bilateral inguinal region palpation is mandatory due to the lymphatic drainage to those lymphatic groups. Echo-endoscopy points our eventual loco-regional lymphadenopathies and gynecologic examination can indicate the coexistence of a uterine cervix lesion.

The diagnostic of certainty is based on histopathologic examination. Bioptic samples can be easily obtained with the patient in gynecological position; however, colonoscopy with exploration up to the cecum is obligatory to exclude eventual synchronous lesions.

As with other paraclinical investigations, a CT examination of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis or an MRI is recommended to point out possible secondary tumors.

Treatment

Squamous cell carcinoma represents 80% of all anal canal cancers. Untill the 1970s, standard treatment consisted in abdominoperineal rectal amputation. However, despite the radical nature of the surgical intervention, local recurrence rate was around 47% and 5-year survival rate varied between 40% and 70%(19). For patients having small lesions, a large local excision has been proposed, accompanied however by disappointing results, excepting patients with a smaller than 2 cm anal margin cancer(20). Currently, the treatment is based on chemo-radiotherapy of curative intent, surgery being reserved for patients presenting with recurrences or residual disease after primary therapy (radio-+chemotherapy).The place of surgery in anal canal cancer

Up to 40% of anal cancer patients present with residual disease after the completion of primary therapy or have local tumor relapse(21). Abdominoperineal rectal amputation is the standard salvage therapy for patients who develop local recurrences. After salvage therapy, 5-year survival rate is of 22-47%(22). Patient selection for surgery is extremely important and should include a CT/MRI to exclude metastatic disease or pelvic bone invasion and, ideally, also a PET-CT, an investigation that can distinguish between post-radiotherapy changes and those of tumoral nature. Only approximately 50% of the patients with local relapse are eligible for salvage therapy. Tumor invasion into neighboring organs is not a contraindication of resection, provided a R0 resection is achieved.Patient morbidity after “salvage” rectal amputation is high, the most important complications being those related to wound infection. Up to 66% of the patients require more than 3 months for a complete wound healing, over 35% of the patients developing perineal wound dehiscence(23). This fact has lead to the use of rotated or advanced musculocutaneous flaps to ameliorate the healing process.

Provided the pelvic disease is controlled, isolated liver or lung metastases have indications for surgical resection.

Inguinal lymphadenopathies

Up to 25% of the patients develop inguinal lymphadenopathies that are usually unilateral(24). Due to significant morbidity and the relatively low impact on survival, prophylactic inguinal lymphadenectomy is not recommended(25). Inguinal lymphadenectomy is indicated for patients with voluminous lymphatic blocks or to those with an obvious lymphadenopathy after chemo-radiotherapy(26).

Some authors recommend for synchronous lymphadenopathies inguinal lymphadenectomy with chemo- and radiotherapy following the healing of the wound. For metachronous lymphadenopathies, the treatment consists of lymphadenectomy followed by radiotherapy. Survival after radical inguinal lymphadenectomy can reach up to 55% in selected cases(27).

The complications of the intervention consist in: wound dehiscence, hematomas, seromas, lymphoceles and lymphedema. n

Bibliografie

1. Greenlee RT, Murray T, Bolden S, et al. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin 2000; 50:7-33

2. Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T et al. Cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2002;52: 23-47.

3. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer incidence in five continents. Vol VII, Lyon, France: IARC, 1997.

4. Wolff BG, Fleshman JW et al. The ASCRS Texbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. Springer 2007.

5. AJCC Manual for Staging of Cancer. 5th Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven; 1997. p. 91-3.

6. Klas JV, Rothenberger DA, Wong WD, et al. Malignant tumors of the anal canal: the spectrum of disease, treatment, and outcomes. Cancer 1999; 85(8):1686–93-

7. Tan GY, Chong CK, Eu KW, Tan PH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the anus. Tech Coloproctol 2003; 7:169-172.

8. Holly EA, Whittemore AS, Aston DA, Ahn DK, Nickoloff BJ, Kristiansen JJ. Anal cancer incidence: genital warts, anal fissure or fistula, hemorrhoids, and smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81:1726-1731.

9. Daling JR, Weiss NS, Hislop TG et al. Sexual practices, sexually transmitted diseases, and the incidence of anal cancer. N Engl J Med 317:973-7.

10. Frisch M, Glimelius B, van den Brule AJ et al. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. 1997. N Engl J Med 337: 1350-8.

11. Declety G - Cancer de canal anal in Les cancers digestifs. Springer, 2007.

12. Palefsky JM, Holly EA, Gonzalez J et al. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in anal intraepithelial neoplasia and anal cancer. Cancer Res 51: 1014-9.

13. Daling JR, Sherman KJ, Hislop TG, et al. Am J Epidemiol. 1992 Jan 15;135(2):180-9.

14. Frish M, Glimelius B, Wohlfahrt J, et al. Tobacco smoking as a risk factor in anal carcinoma: an antiestrogenic mechanism? J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:708.

15. Mullerat J, Northover J. Human papilloma virus and anal neoplastic lesions in the immunocompromised (Transplant) patient. Semin Colon Rectal Surg 2004; 15:215-217.

16. Deniaud-Alexandre E, Touboul E, Tiret E, et al. Results of definitive irradiation in a series of 305 epidermoid carcinomas of the anal canal. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 56: 1259–1273.

17. Gerard JP, Chapet O, Samiei F, et al. Management of inguinal lymph node metastases in patients with carcinoma of the anal canal: experience in a series of 270 patients treated in Lyon and review of the literature. Cancer 2001; 92:77-84.

18. UKCCCR. Epidermoid anal cancer: results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, and mitomycin. UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party. UK Co-ordinating Committee on Cancer Research. Lancet 1996; 348:1049-1054.

19. Ryan DP, Mayer RJ. Anal carcinoma: histology, staging, epidemiology, treatment. Curr Opin Oncol 2000; 12:345-352.

20. Golden GT, Horsley JS. Surgical management of epidermoid carcinoma of the anus. Am J Surg. 1976; 131(3):275-280.

21. Papaconstantinou HT, Bullard KM, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD. Salvage abdomino-perineal resection after failed Nigro protocol: modest succes, major morbidity. Colorectal Dis. 2006; 8(2):124-129.

22. Ellenhorn JD, Enker WE, Quan SH. Salvage abdominoperineal resection following combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anus. Ann Surg Oncol 1994; 1: 105-110.

23. Mullen JT, Rodriguez – Bigas MA, Chang GJ, et al. Results of surgical salvage after failed chemoradiation therapy for epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007; 14(2):478-483.

24. Klas JV, Rothenberg DA, Wong WD, Madoff RD. Malignant tumors of the anal canal: the spectrum of disease, treatment and outcomes. Cancer. 1999; 85(8):1686-1693.

25. Welch JP, Malt RA. Appraisal of the treatment of carcinoma of the anus and anal canal. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1977; 145:837-844.

26. Swan MC, Furniss D, Cassell O. Surgical management of metastatic inguinal lymphadeopathy. BMJ. 2004;329(7477):1272-1276.

27. Greenall MJ, Magill GB, Quan SH, DeCosse JJ. Recurrent epidermoid cancer of the anus. Cancer 1986;57:1437-1441.

28. Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region. 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; 42:1200-1202.

29. Cummings BJ. Oncology 1996; 10: 1853-1854.

30. Jensen SL, Hagen K, Shokouh-Amri MH, Nielsen OV. Does an erroneous diagnosis of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal canal and anal margin at first physician visit influence prognosis? Dis Colon Rectum 1987; 30: 345-351.

31. Wade DS, Herrera L, Castillo NB, Petrelli NJ. Metastases to the lymph nodes in epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal studied by a clearing technique. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1989; 169: 238-242.

Articole din ediția curentă

PREZENTARE DE CAZ

Cancer pulmonar non-microcelular cu metastaze tiroidiene și de parotidă la diagnostic și remisiune completă după tratament. Prezentare

Dan Ilie-Damboiu, Alexandru Grigorescu

Cancerul pulmonar este a doua cea mai frecventă neoplazie şi prima cauză de deces asociată neoplaziilor atât la bărbaţi, cât şi la femei. În acest articol, vom prezenta cazul unui pacient nefumător, c...

CANCERUL DE SÂN

Factori de prognostic în cancerul de sân triplu negativ

Silvia Ilie, Inga Botnariuc, Oana Trifănescu, Rodica ANGHEL, Xenia Bacinschi

Cancerul de sân triplu negativ (CSTN) este o boală agresivă chiar și în stadiile inițiale. Există o rată de recidivă de 30% în primii 5 ani în stadiile I-III operate per primam. Prin analiza expresiei genelor, s-a identi...Articole din edițiile anterioare

AI IN MEDICAL DECISION

Legal implications of physician liability in the use of artificial intelligence for diagnosis and treatment

Virgiliu Mihail Prunoiu, Ovidiu Juverdeanu, Codruţa Cosma, Eugen Brătucu, Laurenţiu Simion, Victor Strâmbu, Adrian-Radu Petru, Mircea-Nicolae Brătucu

Inteligenţa artificială (IA), prin multiplele sale avantaje, precum îmbunătăţirea şi acurateţea diagnosticului şi reducerea vo...

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Risks, survival and prognosis in female patients with breast cancer who developed bone metastases – a retrospective study

Cătălina Teodorescu, Elena Chitoran, Mihnea Alecu, Dan Luca, Vlad Rotaru, Ciprian Cirimbei, Sânziana Ionescu, Dragoş Şerban, Laurenţiu Simion

Cancerul mamar prezintă cea mai ridicată incidenţă dintre toate tipurile de cancer, cu 46,2 cazuri la 100000 de locuitori şi,...

REVIEW