Neuroendocrine cancer, often known as a neuroendocrine tumor (NET) or neuroendocrine neoplasm, originates from the specialized cells of the neuroendocrine system. These cells have characteristics that are indicative of both endocrine cells and nerve cells. Neuroendocrine tumors mostly arise inside the gastrointestinal tract, with the large intestine accounting for 20% of cases, followed by the small intestine (19%) and the appendix (4%). In order to provide a comprehensive literature review of neuroendocrine tumors that start from the small bowel, the used methodology included performing a thorough investigation of the primary attributes of NETs by using renowned academic databases, such as PubMed, Scopus and Academic Oxford Journals. The findings were classified into four distinct groups: a) genetics, epidemiology and pathology; b) clinical aspects; c) paraclinical aspects; d) treatment and prognosis. Although there is a possibility of encountering both local and systemic complications, nevertheless, it is important to note that neuroendocrine tumors are associated with rather positive survival rates in the long run (five-year and ten-year survival, respectively).

Neuroendocrine tumors of the small bowel: a literature review

Tumori neuroendocrine ale intestinului subţire: review de literatură

First published: 18 decembrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/OnHe.65.4.2023.8951

Abstract

Rezumat

Cancerul neuroendocrin, adesea cunoscut sub numele de tumoră neuroendocrină (NET) sau neoplasm neuroendocrin, provine din celulele specializate ale sistemului neuroendocrin. Aceste celule au caracteristici specifice atât celulelor endocrine, cât şi celulelor nervoase. Tumorile neuroendocrine pot avea drept punct de plecare tractul gastrointestinal, intestinul gros reprezentând 20% din cazuri, urmat de intestinul subţire (19%) şi de apendice (4%). Pentru a prezenta un review cuprinzător al literaturii de specialitate privind tumorile neuroendocrine având drept punct de plecare intestinul subţire, metodologia utilizată a inclus efectuarea unei investigaţii amănunţite asupra atributelor primare ale NET, prin utilizarea bazelor de date academice cunoscute, cum ar fi PubMed, Scopus şi Oxford Academic. Rezultatele au fost clasificate în patru grupe distincte: a) genetică, epidemiologie şi patologie; b) aspecte clinice; c) aspecte paraclinice; d) tratament şi prognostic. Deşi există posibilitatea apariţiei atât a complicaţiilor locale, cât şi sistemice, este important de menţionat faptul că tumorile neuroendocrine sunt asociate cu rate de supravieţuire pozitive pe termen lung (privind supravieţuirea la cinci şi, respectiv, zece ani).

1. Introduction

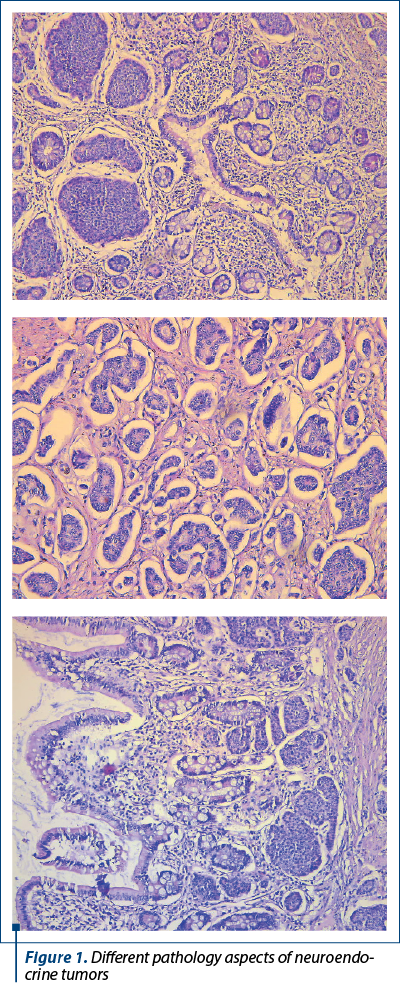

The lung, small intestine, pancreas and appendix are among the most often affected anatomical locations of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). They predominantly manifest as solitary or multiple lesions in the distal small intestine. Small intestine neuroendocrine tumors (SI-NET) are characterized by their essentially dormant nature; however, they are also the most frequently metastasized neuroendocrine tumors, with 60-80% of patients presenting with liver metastases. Regarding the pathology aspects (Figure 1), as presented also by Cuthberson et al. (2023)(1), there are different degrees of aggressiveness, ranging from well-differentiated, grade 1 neuroendocrine tumors, to poorly differentiated grade 3 and neuroendocrine carcinomas.

Imprecise, nonspecific symptoms that are readily ascribed to alternative innocuous conditions contribute to the diagnostic delay, as shown by Lim and Pomier (2021)(2). Their secretory feature has the potential to induce symptoms, namely weight loss and diarrhea, as emphasized also by Zammit and Sidhu (2023)(3).

2. Materials and method

The following searches were conducted to perform an updated literature review on neuroendocrine tumors of the small bowel: 1) a search for the relevant terms (“neuroenedocrine tumor AND small bowel”) on www.pubmed.gov was carried out, performed on 13.11.2023, which yielded only 36 results, after the application of the following filters: “English language”, “published in the last 5 years”, “adult humans”, “clinical trial”, “meta-analysis”, “RCT”, “review” and “systematic review”; 2) another search was performed on www.scopus.com for the terms “small AND bowel AND neuroendocrine AND tumor”, with the selection of the filters: “medicine”, “final stage of publication”, “keyword NET”, “language English”, “source type Journal”, “2019-2023”, which returned 47 results; 3) the terms “neuroendocrine tumor AND small bowel” were searched on https://academic.oup.com, with the supplementary fields of “review article”, “research article”, “published from November 2019 to November 2023”, “subject: medicine and health”, and the search returned 164 results. The above findings (from searches 1-3) were further selected by setting the language to “English”, and duplicates and results not consistent with the subject were eliminated. Furthermore, the remaining results retrieved for our topic were summarized into four main aspects of “neuroendocrine tumors of the small bowel”. Those four aspects are: a) genetics; epidemiology and pathology; b) clinical; c) paraclinical; d) treatment and prognosis.

3. Results

3. a) Genetics, epidemiology and pathology aspects

In a research that looked into the incidence of small bowel cancer, Bouvier et al. (2020)(4) showed that the most prevalent histological type seen in this study was adenocarcinoma, accounting for 38% of cases. Neuroendocrine tumors were the second most frequent type, including 35% of cases. Lymphoma and sarcoma accounted for 15% and 12% of cases, respectively. There were observed variations in the age at diagnosis and tumor site between adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors. The prevalence of all four types of tumors showed a substantial rise across the span of two decades, except for lymphoma in males. On the contrary, in a study from 2021, by Eriksson et al. (2021)(5), neuroendocrine tumors were the most common small bowel malignancies, and they presented with a threefold increase in incidence. However, the existing literature does not provide sufficient evidence to determine if this increase is attributable to a genuine greater occurrence, or if it is only a result of factors such as advancements in diagnostic techniques.

Notwithstanding a growing prevalence, the precise processes that contribute to the underlying illness have yet to be discovered. Recent investigations have established a notable association between the emergence of SI-NETs and the presence of Lynch syndrome (LS) as well as MUTYH mutations. The findings of the group conducted by Helderman et al. (2022)(6) did not provide evidence for a correlation between the development of SI-NET and LS or MUTYH mutations. The authors also mentioned that, to get a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of SI-NET and effectively address patient’s management, it is imperative for future research to prioritize the investigation of additional potential genes.

Several studies have described a notable disparity in the occurrence and prognosis of small-intestine neuroendocrine tumors between male and female patients, with male individuals exhibiting a higher prevalence and poorer outcomes. In research published by Blazevic et al. (2022)(7), the expression of estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and 2 (ESR2), progesterone receptor (PGR), and androgen receptor (AR) messenger RNA (mRNA) was evaluated in primary tumors and healthy intestinal tissues. An immunohistochemical analysis was conducted to assess the expression of estrogen receptor alpha (ERa) and androgen receptor (AR) proteins, in both original tumors and mesenteric metastases. The co-occurrence of elevated ERa and AR expression within the milieu of SI-NET indicates a potential regulatory function of sex hormones in the progression of mesenteric metastasis and fibrosis, which are distinctive features of SI-NET.

Regarding the tumors of the minor papilla/ampulla, a study by Vanoli et al. (2019)(8) described neuroendocrine tumors occurring in the minor papilla/ampulla (MIPA) as few and too scarcely researched. A total of 16 multiple intraepithelial neoplasia of pancreas (MIPA) neuroendocrine tumors were gathered with the purpose of examining their clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical characteristics. The investigation encompassed the evaluation of several markers, such as somatostatin, pancreatic polypeptide, gastrin, serotonin, MUC1, cytokeratin 7 and somatostatin. In a manner consistent with the findings in the main ampulla, three distinct histotypes were identified. (i) The study in question examined ampullary-type somatostatin-producing tumors (ASTs) in 10 cases. These tumors were characterized by the expression of somatostatin in most tumor cells and the presence of focal-to-extensive tubulo-acinar structures, often accompanied by psammoma bodies. Additionally, these tumors show reactivity to MUC1 and exhibit no or rare membranous reactivity for somatostatin receptor type 2A. (ii) The study also included three cases of gangliocytic paragangliomas. These tumors were characterized by the presence of three distinct cell types: epithelioid cells, which often show reactivity for pancreatic polypeptide; ganglion-like cells; and S100 reactive sustentacular/stromal cells. (iii) Lastly, the research included three cases of ordinary nonfunctioning neuroendocrine tumors. In summary, mucinous intraductal papillary neoplasms of the pancreas with an associated invasive carcinoma (MIPA NETs) have significant similarities to tumors originating in the main ampulla, particularly with a higher incidence of ASTs. Additionally, these tumors commonly expressed somatostatin receptors of the types 2A and 5.

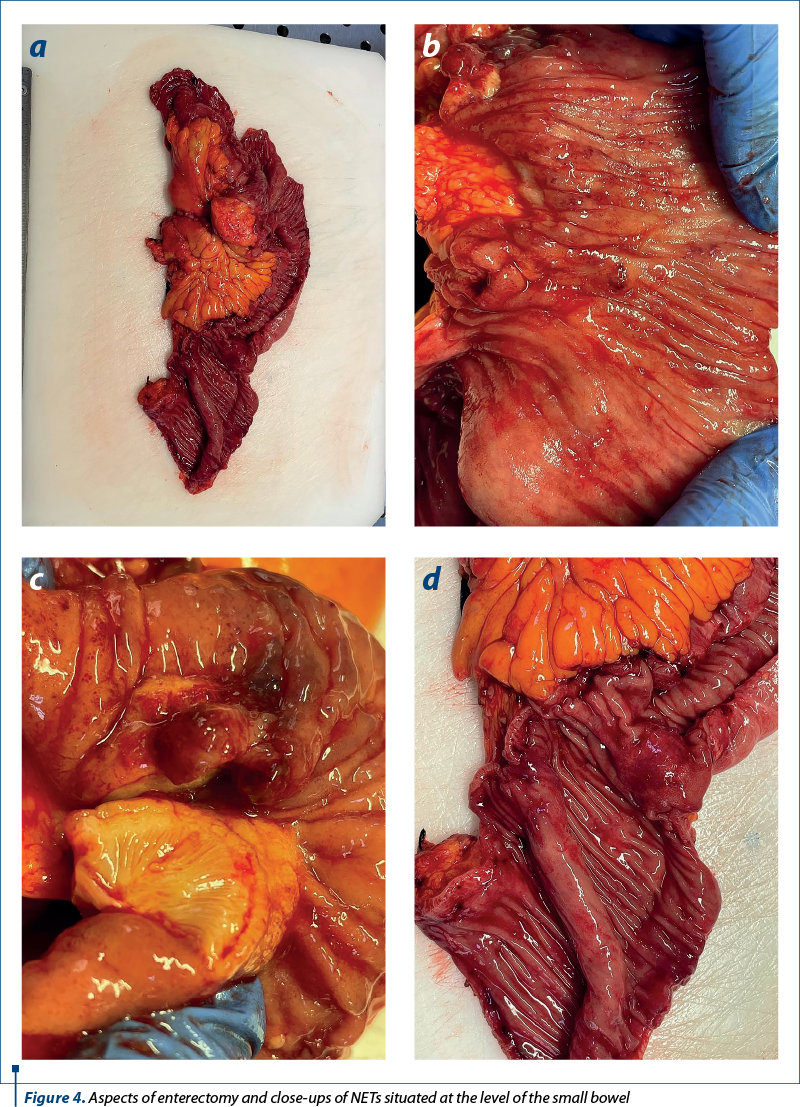

Kalifi et al. (2021)(9) showed that multiple ileal NET are generally found left of the SMA axis. In current surgical literature, the prevalence of multifocal tumors (MFT) in small bowel neuroendocrine tumors (SB-NET) has been reported to reach up to 50%. Familial variants of SB-NET have a notably elevated incidence of malignant functional tumors (MFTs), with rates reaching over 80%. Makinen et al. (2021)(10) work revealed significant genetic heterogeneity in multifocal ileal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), underscoring the need of identifying and excising all original tumors that possessed metastatic potential, as well as the necessity for refined targeted therapeutic approaches.

Metastatic neuroendocrine tumors most often originate in the small bowel and pancreas. Some SB-NET patients have synchronous or metachronous pancreatic NETs (PNETs), which may be primary or metastatic. Small bowel and pancreatic NETs were identified in 3% of individuals in the research presented by Scott et al. (2019)(11). The pancreatic tumor was a metastasis from the SB-NET primary in nearly two-thirds of evaluable individuals and a distinct primary in one-third.

Regarding the co-occurrence of small bowel cancer and inflammatory bowel disease, we cite the work of Yu et al. (2019)(12), who conducted a cohort research including the whole population of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Norway and Sweden between the years 1987 and 2016. The goal of this research was to assess the level of risk associated with small bowel adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors in individuals diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). After studying a cohort of 142,008 patients, with a median follow-up duration of 10 years, it was shown that individuals diagnosed with both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease had an almost twofold higher susceptibility to also present neuroendocrine tumors.

The co-occurrence of adenocarcinoma of the colon and neuroendocrine tumor (NET) of the small bowel has been documented in prior literature on Crohn’s disease. However, the simultaneous presence of both neoplasms is very uncommon, as shown by Azzam (2021)(13).

The objective of the study of Malczewska et al. (2021)(14) was to prove that the use of serum-based microRNA (miRNA) biomarkers in the context of small-bowel neuroendocrine tumors hold potential in providing valuable guidance for clinical decision-making. The conclusion was that the potential use of serum miR-125b-5p and miR-362-5p in the detection of residual disease or recurrent disease was worth considering.

3. b) Clinical aspects

3. b) 1. Non-metastatic forms

Several articles, among which we cite those by Reed et al. (2023)(15), described that jejunal neuroendocrine tumors could manifest as incidental intraoperative findings during surgery for some other associated pathologies.

Several case reports, among which those of Patane et al. (2020)(16), described a small bowel NET tumor as a cause of small bowel obstruction, with good survival rates, depending on the distinction and size of the (tumor) growth.

A case report presented by Lee et al. (2019)(17) revealed findings such as abdominal mass and abdominal pain as presentation forms of an ileum located small bowel carcinoma. Furthermore, abdominal pain appearing as a symptom of both appendicitis and mesenteric vein thrombosis (as rare complications of a small bowel neuroendocrine tumor) was described by Bachelani (2022)(18). On the subject of abdominal pain, palpable abdominal mass and vomiting, we cite the case report of Jagtap et al. (2020)(19).

The surgical management of a multifocal neuroendocrine tumor in the small bowel that manifested as an incarcerated incisional hernia represented a significant challenging circumstance, as emphasized by Steinkraus et al. (2021)(20).

Gastrointestinal bleeding can also be present among the symptoms of neuroendocrine tumors of the small bowel, as underlined by Teh et al. (2019)(21).

Leite et al. (2020)(22) described the association between von Recklinghausen disease and a duodenal neuroendocrine tumor, which manifested with persistent vomiting.

3. b) 2. Metastatic forms

Regarding the metastatic forms of disease and their manifestations, Nan and Dharmawardhane (2022)(23) described a case of concurrent suprasternal and cardiac metastasis, both characterized as “exceedingly rare” and “rare”, respectively.

Fernandez-Christlieb et al. (2022)(24) provided a clinical case involving a 55-year-old female patient who presented with a distressing nodule located in the right breast. The histopathological observations aligned with a well-differentiated (G2) metastatic neuroendocrine tumor (NET), originating from the gastrointestinal tract.

The case study presented by Carlaw et al. (2023)(25) described a 68-year-old female patient who was diagnosed with ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. This condition was attributed to the overproduction of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from original lesions in the small bowel and metastases in the mesentery.

3. c) Paraclinical aspects

Various imaging modalities are employed in the identification, classification and monitoring of lesions in individuals with confirmed or suspected neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN), as presented by Navin et al.(26-28) These modalities encompass CT enterography, MR enterography and PET/CT, utilizing a somatostatin receptor analogue. The utilization of FDG PET/CT imaging modality might potentially play a significant role in the assessment of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs). The use of liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly when employing a contrast agent that specifically targets hepatocytes, is recommended for the assessment of hepatic metastases. The use of medical imaging plays a crucial role in guiding decisions pertaining to surgical techniques and the administration of systemic therapy, particularly in the context of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy.

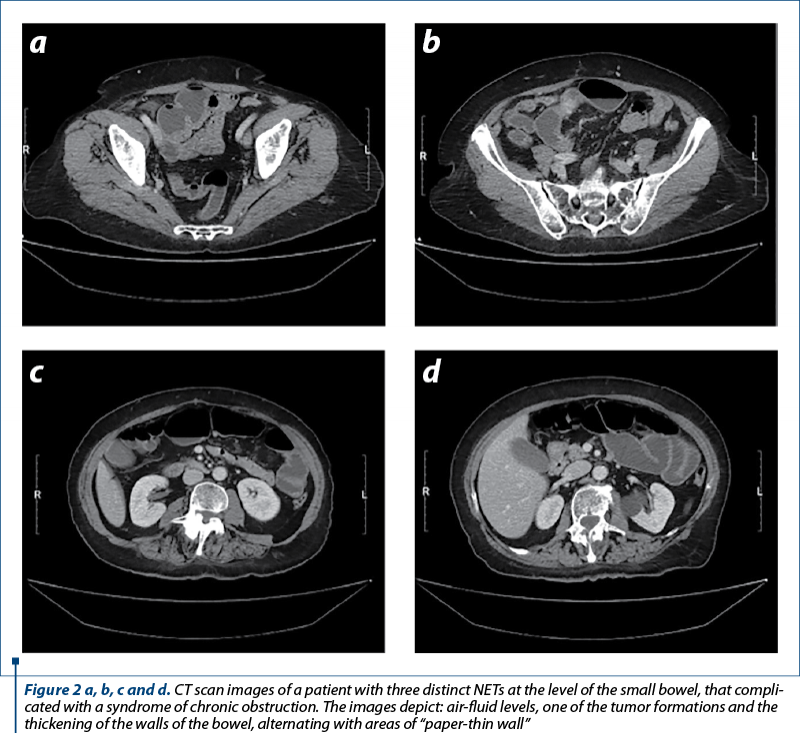

The importance of computed tomography (Figure 2) in the diagnosis of NETs and its ability to detect abdominal masses and perforations are underlined in a study by Cîmpeanu et al. (2019)(29). In research presented by Deguelte et al. (2022)(30), two readily identifiable factors – the existence of a visible primary tumor and/or mesenteric masses in contact with the superior mesenteric vessels (for at least 180°, during the initial cross-sectional imaging) – can both assist clinicians in determining the optimal timing and type of surgery for SI-NENs.

Endoscopic ultrasonography is cited as a diagnostic means for a pancreatic metastasis from a small neuroendocrine tumor, as explained by Addeo et al. (2023)(31). Moreover, as conventional imaging is ineffective in detecting locoregional nodes and micrometastases in duodenal NENs, Massironi et al. (2020)(32) showed that endoscopic ultrasonography should be included in preoperative tools for more accurate local staging when considering conservative options like endoscopy or surgical excision.

Capsule endoscopy is a major pillar of small bowel investigation, but there were cases (Symeonidis et al., 2021(33)) which reported capsule retention complicating with bowel obstruction.

A study by Zhao et al. (2020)(34) demonstrated the feasibility of utilizing double contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for the identification of small intestine neuroendocrine tumors. This strategy may be considered as a viable method to aid in the diagnosis of small intestinal tumors.

CT enterography is an efficient method in finding small bowel neuroendocrine tumors, as shown by Kim et al. (2020)(35), who also emphasized the crucial role of endoscopy, employed with the same purpose.

The utilization of Ga-DOTATOC PET-CT imaging has a substantial influence on the clinical care of individuals diagnosed with neuroendocrine tumors, according to a study by Ghobrial et al. (2020)(36).

Discontinuation before imaging is still suggested due to the unknown interactions between cold somatostatin analogues (cSAs) and radiolabeled ones. A comprehensive review by Morland et al. (2023)(37) examined how cSA affects tumoral and healthy organ somatostatin receptor (SSTR), using SPECT or PET. No cSA-induced SSTR imaging quality loss has been shown. On the contrary, cSAs appear to enhance tumor-environment contrast.

By thus emphasizing the importance of EKG in the general evaluation of the patient, we cite the research by Said et al. (2020)(38), who showed that the presence of left bundle branch block indicated the manifestation of a primary carcinoid tumor in the small intestine (which had subsequently spread to the interventricular septum).

Importantly, small bowel cancer causes terminal ileitis more often. Screening colonoscopy with ileal intubation can detect these lesions early, as emphasized by Kahveci et al. (2023)(39).

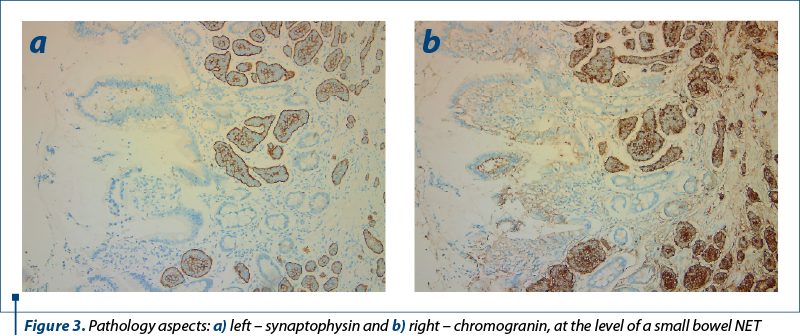

The presented data in an article by Polydorides and Liu (2022)(40) provide support for the notion that small bowel NET diagnosis should rely on either chromogranin or synaptophysin (Figure 3).

3. d) Treatment and prognosis

3. d) 1. Of unique lesions

Among others, Dawod et al. (2021)(41) emphasized that interdisciplinary approach is necessary. Over the past decade, large randomized clinical trials with somatostatin analogues (PROMID, CLARINET) or peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) with 177-lutetium (NETTER-1) or the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor (mTOR) everolimus (RADIANT) have advanced the medical treatment of unresectable grade 1 and 2 SBNETS. New medicines like TKIs are cutting-edge. Cives et al. (2019)(42) emphasized that, in general, the immune environment of SB-NETs is diverse, with duodenal NETs exhibiting the predominance of adaptive immune resistance mechanisms.

Regarding surgical resection, as presented by Koea et al. (2021)(43), SB-NETs have three subtypes: type A – SBNET with resectable mesenteric illness without root involvement; type B – “borderline resectable” SB-NET with mesenteric nodal metastases and fibrosis adjacent, but not encasing the main trunk of the SMA and SMV; and type C – “locally advanced or irresectable” SB-NET with tumor deposits and fibrosis encasing the SMA and SMV. The encasement of mesenteric vessels in mesenteric metastases originating from small bowel neuroendocrine tumors poses a significant surgical obstacle. According to Kasai et al. (2019)(44), when reaching dimensions beyond 2 centimeters in diameter, a mesenteric mass suggests an aggressive tumor biology. In another study, in 86% of the cases treated with endovascular occlusion and tumor excision (EVOTE), the mesenteric mass was entirely surgically removed. The mortality and morbidity rates at the 30-day mark were 0% and 29%, respectively, as described by Horwitz et al. (2019)(45). In a National Cancer Database study, Bangla et al. (2022)(46) demonstrated that resection of non-metastatic small bowel neuroendocrine tumors prolonged the overall survival. As seen in an article signed by Watanabe et al. (2023)(47), priority should be given to imaging less frequently over an extended period of time in order to detect clinically significant recurrences that are treatable and that could enhance the overall survival (OS).

SI-NETs should have main tumors, regional lymph nodes, and peritoneal carcinomatosis removed. Exploratory laparotomy with manual small intestine palpation is recommended to find SI-NETs, whether small or multiple lesions. No high-quality data supports surgical recommendations for SI-NETs with peritoneal carcinomatosis; however, cytoreductive surgery has proven long-term survival, as indicated by Draskacheva et al. (2023)(48). Moreover, a study by Wonn et al. (2021)(49) showed that small intestinal neuroendocrine tumor-related peritoneal carcinomatosis could be cytoreduced. In which concerns the surgical treatment, Kacmaz et al. (2021)(50) emphasized that hospital volume may affect the postoperative outcomes, according to current evidence.

Hajjar et al. (2022)(51) studied the impact of HIPEC upon survival and reached the conclusion that patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery who have SB-NET do not appear to experience any additional advantages in terms of postoperative evolution or survival when HIPEC is utilized. On the contrary, it is correlated with increased morbidity. Further research is necessary to validate the hypothesis that it could potentially result in an enhanced survival rate free from recurrence.

Research by Zaidi et al. (2019)(52) suggested that a thorough regional lymphadenectomy might be necessary for the accurate staging and management of small bowel neuroendocrine tumors in patients undergoing curative-intent resection. Patients with four or more positive lymph nodes had a lower three-year recurrence-free survival than those with one to three or zero positive lymph nodes.

The resection of lymph node metastases near major mesenteric arteries may jeopardize the residual intestine after surgery for SB-NEN. Safe perfusion assessment during gastrointestinal surgery is possible with fluorescence angiography (FA), which, as shown in a study presented by Kacmaz et al. (2021)(53), lead to an 80% change in the surgical technique.

McGuiness et al. (2021)(54) showed that patients who underwent complete resection and had stages I or II of disease did not experience any recurrence.

Laparoscopic surgery may overlook multifocal tumors in small bowel net therapy. Due to lymph node and mesentery involvement, laparoscopic visceral excision may be difficult and not radical, as presented by Pino et al. (2022)(55). On the contrary, successful and long-term results of laparoscopy in neuroendocrine tumors were presented by Dapri and Bascombe (2019)(56). Moreover, the benefits of minimally invasive surgery were presented by Wong et al. (2022)(57), who underlined that the application of MIS to the treatment of SB-NETs in stages I-III has increased, particularly in centers with higher volume. In his research, there was no evidence of a reduced lymph node (LN) harvest in the MIS cohort in comparison to the open surgery cohort.

In a study by Rajaretnam et al. (2021)(58), surgical bypass (jejuno or ileocolic) should be performed on patients with advanced disease, whenever resection is not possible.

In duodenal NETS(D-NETS), Ki67 index tumor grading greatly affects the patient outcome. Lucandri et al. (2022)(59) and Xie et al. (2022)(60) showed that endoscopic resection is advised for lesions below 2 cm, pancreaticoduodenectomy for large duodenal NETs, and Whipple surgery for duodenal origin and gastric antrum contiguity. In a study reported by Tran et al. (2022)(61), in 1-2 cm duodenal NETs, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and surgical resection (SR) lead to similar survival after age adjustment. EMR may save recurrences. Surgical resection increased progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival in duodenal NETs compared to jejunoileal NETs. Gamboa et al. (2019)(62) further debates that, regardless of tumor size, patients with nonmetastatic and nonfunctional D-NETS should be considered for resection. In light of the absence of prognostic value, the selection of resection type and extent of LN retrieval should be customized to the clinical profile and safety profile of individual patients.

Kleinschmidt and Christein (2020)(63) showed that size does not affect the biological behavior of ampullary NETs, which are more aggressive than non-ampullary tumors. Radical resection by Whipple surgical procedure is recommended for individuals at tolerable surgical risk.

Ziogas et al. (2023)(64) researched mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC) of the ampulla of Vater and found that early identification and management are difficult but necessary to enhance results, as many patients are discovered late and have poor outcomes. For instance, adjuvant chemotherapy was given to 61.8% of patients after tumor excision (mainly pancreaticoduodenectomy, done in 96.3%). Nearly half the batch had disease recurrence, and 42.1% died after a median follow-up of one year. In a case report by Yoshimachi et al. (2020)(65), a patient had MANEC with a 40% neuroendocrine carcinoma component. Neuroendocrine cancer spread to posterior pancreatic lymph nodes. Within four months of surgery, computed tomography showed numerous liver metastases despite adjuvant S-1 treatment. A comprehensive approach with chemotherapy is essential in such cases.

Endoscopic papillectomy as a treatment option was also studied by Shimai et al. (2020)(66), who considered that small-grade and low-grade ampullary NETs without metastases may be cured.

Somatostatin analogues are the first-line treatment for well-differentiated small bowel neuroendocrine tumors (Wd-SBNETs), although PRRT is sometimes used as a second-line treatment. The ideal therapeutic sequence for third-line therapy is difficult to determine due to inadequate prospective evidence. According to Lamarca et al. (2021)(67), everolimus was the most common third-line treatment. Ki-67, progression rate, functioning and tumor load were key deciding considerations.

A study by Brighi et al. (2020)(68) showed that somatostatin analogues promote gallstone formation and complications among neuroendocrine tumor (NET) patients. Gastrointestinal NETs and surgery are independent risk factors for biliary stone disease. Prophylactic cholecystectomy should be considered for all patients with primary gastrointestinal NET or having abdominal surgery.

In comparison to the other groups, in a study signed by Maurer et al.(51), patients who received both peptide radioreceptor therapy (PRRT) and primary tumor resection and mesenteric lymph node dissection had the highest survival rate. Retreatment with PRRT may be a viable alternative in situations where the disease recurs, as it was exemplified by Rinzivillo et al. (2021)(69).

Regarding the treatment of symptoms, Larouche et al. (2019)(70) mentioned carcinoid syndrome, that could well be treated with somatostatin analogues and refractory diarrhea, with telotristat etiprate as a therapeutic option.

3. d) 2. Of metastatic forms

Metastatic forms and their various treatment options were also described by Agarwal and Mohamed (2022)(71).

Most small intestinal tumors are well-differentiated, low-grade neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Despite their slow development and grade, these tumors spread; at presentation, 50% have nodal metastases and 30% have distant metastases, even though they may survive long, as shown in research presented by Grillo et al. (2022)(72). According to the same researchers, MTDs and non-LN-associated neoplastic deposits in the mesenteric perivisceral adipose tissue appear to be a better prognostic indicator than nodal metastases in small bowel NETs. As presented also by Symons et al. (2023)(73), despite the fact that poorly differentiated NETs are typically treated with chemotherapy, their prognoses are inferior to those of well-differentiated NETs.

Draskacheva et al. (2023)(48) concluded in their research that SI-NET patients with large hepatic and peritoneal metastases and bowel dysfunction should consider surgery for symptom alleviation, an idea also supported by Gupta et al. (2022)(74). A downside to this idea would be the fact that patients with neuroendocrine liver metastases who require concurrent pancreaticoduodenectomy in addition to liver resection have a substantially heightened susceptibility to developing infectious complications, as shown by Acosta et al. (2019)(75).

Another article that spoke in favor of surgery in metastatic disease is the one by Hallet et al. (2021)(76), in which is mentioned that a NET-experienced surgeon should evaluate all stage IV SB-NET patients for surgical options, including primary tumor excision despite metastatic disease. Moreover, in research presented by Gangi and Anaya (2020)(77), it was mentioned that metastatic patients should be examined individually for surgical treatments to reduce bowel symptoms (pain, intestinal angina, blockage) and carcinoid symptoms (flushing, diarrhea, hemodynamic instability) and prolong survival. Furthermore, even with unresectable metastatic cancer, vigorous surgical care of these individuals can improve symptoms and long-term survival, unlike other gastrointestinal malignancies, a conclusion also emphasized by Bennett et al. (2022)(78) and Rafael et al. (2017)(79).

Capecitabine/temozolomide (CAPTEM) works in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs); however, small bowel NET evidence is scarce. In a batch reported by Al-Toubah et al. (2022)(80), patients with low-intermediate grade tumors had poor response rates, whereas those with high-grade cancer had greater rates. CAPTEM should be reserved for higher-grade small bowel NETs, according to our findings.

3. d) 3. Predictors

Extramural venous invasion (EMVI) is prevalent in small bowel NETs and correlates significantly with the development of liver metastases, according to Liu and Polydorides (2020)(81) findings. Consequently, its evaluation is crucial and, if necessary, should be conducted in conjunction with adjuvant techniques like elastin staining. Moreover, consideration should be given to incorporating EMVI into pathology reporting guidelines.

As presented by Manguso et al. (2019)(82), SB-NET survival at five years was affected by liver disease resection, which was not correlated with survival at 10 years. More than 10 liver lesions and chemotherapy predicted mortality.

According to the research presented by Sherman et al. (2014)(83), higher pancreastatin levels significantly worsen SB-NET’s progression-free survival and overall survival. This impact is independent of age, initial tumor location, and nodal or metastatic illness. Pancreastatin helps identify surgical patients at high risk of recurrence who may benefit from innovative therapy. Moreover, Woltering et al. (2019)(84) concluded that pancreastatin could also predict the outcome of surgical cytoreduction.

Khetan et al. (2020)(85) found, in a single-institution analysis published in Pancreas, that age at diagnosis, perineural invasion, and elevated preoperative chromogranin levels may indicate disease progression in surgical patients with advanced grade I or II small bowel neuroendocrine tumors, who had received multimodal treatment. Moreover, Chatani et al. (2021)(86) showed that preoperative serum chromogranin A is correlated with a reduced overall survival.

Transporting lactate, pyruvate and ketone bodies are monocarboxylate transporters (MCT), which are cell membrane proteins. The aforementioned energy metabolites are considered waste products by the majority of non-neoplastic cells and need to be exported through MCTs. To generate energy, tumor cells have apparently devised mechanisms to transport these metabolites through MCTs. A high expression level of MCT4 is associated with a better prognosis in SB-NETs, whereas MCT1 had no correlation with survival, according to a study by Hiltunen et al. (2022)(87).

4. Discussion

Even though there are many studies which show an increase in survival (Alfagih et al., 2023(88)), SI-NET patients have a profoundly diminished health-related quality of life (HRQoL), encompassing vitality, health, sleep and sexual activity, despite the implementation of modern treatment approaches, as shown also by Karppinen et al. (2019)(89).

5. Conclusions

The clinical presentation of this condition exhibits variability, including a range of manifestations. These may include the discovery of incidental lesions during cross-sectional imaging, small intestinal obstruction, the occurrence of carcinoid syndrome, or other syndromic presentations such as hypoglycemia arising from insulinoma. In more severe cases, the presentation may include the development of florid carcinoid heart disease. The diagnosis of the condition is dependent upon the use of biochemical indicators, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and functional imaging techniques based on somatostatin receptor. The treatment options for this condition include a wide range of interventions, starting from surgical procedures that aim to achieve complete removal of the illness, to strategies focused on disease stabilization. These techniques involve the use of somatostatin analogues, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), everolimus, sunitinib, liver-directed medicines, and sometimes chemotherapy. Despite the potential occurrence of both local and systemic problems, these complications are linked to quite favorable five-year and ten-year survival rates, respectively.

Author contributions: Conceptualization – S.I., A.N. and L.S.; Methodology – O.L.M., E.C. and V.R.; Resources – E.C., M.M. and O.L.M.; Data curation – S.I.; Writing and original draft preparation – C.C.; Writing, review and editing – A.E., M.R. and A.N..; Visualization – M.M. and C.C.; Supervision – L.S. and S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY licence.

Bibliografie

-

Cuthbertson DJ, Shankland R, Srirajaskanthan R. Diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumours. Clin Med (Lond). 2023;23(2):119-124.

-

Lim JY, Pommier RF. Clinical Features, Management, and Molecular Characteristics of Familial Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:622693.

-

Chetcuti Zammit S, Sidhu R. Small bowel neuroendocrine tumours - casting the net wide. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2023;39(3):200-210.

-

Bouvier AM, Robaszkiewicz M, Jooste V, et al. Trends in incidence of small bowel cancer according to histology: a population-based study. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(2):181-188.

-

Eriksson J, Norlén O, Ögren M, Garmo H, Ihre-Lundgren C, Hellman P. Primary small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors are highly prevalent and often multiple before metastatic disease develops. Scand J Surg. 2021;110(1):44-50.

-

Helderman NC, Elsayed FA, van Wezel T, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency and MUTYH variants in small intestine-neuroendocrine tumors. Hum Pathol. 2022;125:11-17.

-

Blažević A, Iyer AM, van Velthuysen MF, et al. Sexual Dimorphism in Small-intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors: Lower Prevalence of Mesenteric Disease in Premenopausal Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(5):e1969-e1975.

-

Vanoli A, Albarello L, Uncini S, et al. Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs) of the Minor Papilla/Ampulla: Analysis of 16 Cases Underlines Homology With Major Ampulla NETs and Differences From Extra-Ampullary Duodenal NETs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(6):725-736.

-

Kalifi M, Walter T, Milot L, et al. Unifocal versus Multiple Ileal Neuroendocrine Tumors Location: An Embryological Origin. Neuroendocrinology. 2021;111(8):786-793.

-

Mäkinen N, Zhou M, Zhang Z, et al. Whole genome sequencing reveals the independent clonal origin of multifocal ileal neuroendocrine tumors. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):82.

-

Scott AT, Pelletier D, Maxwell JE, et al. The Pancreas as a Site of Metastasis or Second Primary in Patients with Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(8):2525-2532.

-

Yu J, Refsum E, Perrin V, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk of adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors in the small bowel. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(6):649-656.

-

Azzam N. A rare case of rectal adenocarcinoma and small-bowel neuroendocrine Tumor in a young patient with long-standing Crohn’s disease: A case report. Journal of Nature and Science of Medicine. 2021;4(2):209–211.

-

Malczewska A, Frampton AE, Mato Prado M, et al. Circulating MicroRNAs in Small-bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Potential Tool for Diagnosis and Assessment of Effectiveness of Surgical Resection. Ann Surg. 2021;274(1):e1-e9.

-

Reed G, Kim D, Hayes K, Wirz R. Incidental intraoperative finding of jejunal neuroendocrine tumors during elective ventral hernia repair. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(9):rjad530.

-

Patanè E, Sgardello SD, Guendil B, Fournier I, Abbassi Z. Unexpected Finding of a Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Tumor: A Case Report and Literature Review. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e917759.

-

Lee JE, Hong SH, Jung HI, et al. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ileum: case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2019;19(1):135.

-

Bachelani AM. Mesenteric venous thrombosis: a rare complication of small bowel neuroendocrine tumor presenting with gangrenous appendicitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022(3):rjac092.

-

Jagtap S, Phalke A, Naniadekar R, Jagtap SS, Bhoite A. Multiple carcinoid tumor of the ileum presented as intestinal obstruction. Journal of Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences University. 2020;15(3):510.

-

Steinkraus K, Andresen JR, Clift AK, Liedke MO, Frilling A. Multifocal neuroendocrine tumour of the small bowel presenting as an incarcerated incisional hernia: a surgical challenge in a high-risk patient. J Surg Case Rep. 2021;2021(6):rjab219.

-

Teh JW, Fowler AL, Donlon NE, et al. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding resulting from small bowel neoplasia; A case series. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;60:87-90.

-

Leite C, Constantino J, Melo Pinto D, et al. Duodenal neuroendocrine tumour in a young patient with von Recklinghausen disease. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020(3):rjaa039.

-

Nan X, Dharmawardhane A. Rare case of concurrent suprasternal and cardiac metastasis from small bowel neuroendocrine tumour. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022(6):rjac308.

-

Fernández-Christlieb G, Rivera-García-Granados A, Kajomovitz-Bialostozky. Metastatic jejunal neuroendocrine tumor to the breast: Case report and literature review. [Tumor metastásico neuroendocrino de yeyuno a mama: reporte de caso y revisión de la literature]. Gaceta Mexicana de Oncología. 2022;21:64–66.

-

Carlaw KR, Hameed A, Shakeshaft A. A Case of Cushing’s Syndrome from Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Small Bowel and Its Mesentery. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(4):4110-4116.

-

Navin PJ, Ehman EC, Liu JB, et al. Imaging of Small-Bowel Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2023;221(3):289-301.

-

Morse B, Al-Toubah T, Montilla-Soler J. Anatomic and Functional Imaging of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(9):75.

-

Picchia S, Terlizzo M, Bali MA. Radiological and histological findings of an asymptomatic ever-increasing neoplasm: The small bowel neuroendocrine tumor (NET). Curr Probl Cancer. 2020;44(1):100495.

-

Cîmpeanu E, Zafar W, Cîrciumaru I, Prozumenshikov A, Salman S. Rare presentation of small bowel adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation in the jejunum: A case report and summary of diagnostic and management options. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019;11(5):461-464.

-

Deguelte S, Metoudi A, Rhaiem R, et al. Small Intestinal Neuroendocrine Neoplasm: Factors Associated with the Development of Local Tumor-Related Symptoms. Neuroendocrinology. 2022;112(3):252-262.

-

Addeo P, Fattori A, Imperiale A, Bachellier P. Pancreatic metastasis from small bowel neuroendocrine tumor. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55(10):1434-1435.

-

Massironi S, Milanetto AC, Rossi RE, Andreasi V. Risk of Pre-Operative Understaging of Duodenal Neuroendocrine Tumors at Conventional Imaging: When Surgery Becomes the First Choice. Neuroendocrinology. 2020;110 (Suppl1):190.

-

Symeonidis NG, Stavrati KE, Pavlidis ET, et al. Undiagnosed Endoscopy Capsule Retention Causing Delayed Intestinal Obstruction in a Patient with a Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumor. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e932419.

-

Zhao JY, Zhuang H, Luo Y, Su MG, Xiong ML, Wu YT. Double contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of a small intestinal neuroendocrine tumor: a case report of a recommendable imaging modality. Precis Clin Med. 2020;3(2):147-152.

-

Kim S, Marcus R, Wells ML, et al. The evolving role of imaging for small bowel neuroendocrine neoplasms: estimated impact of imaging and disease-free survival in a retrospective observational study. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45(3):623-631.

-

Ghobrial SN, Menda Y, Zamba GK, et al. Prospective Analysis of the Impact of 68Ga-DOTATOC Positron Emission Tomography-Computerized Axial Tomography on Management of Pancreatic and Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas. 2020;49(8):1033-1036.

-

Morland D, Laures N, Triumbari EKA, et al. Impact of Cold Somatostatin Analog Administration on Somatostatin Receptor Imaging: A Systematic Review. Clin Nucl Med. 2023;48(6):467-473.

-

Said SM, Nijjar P, Klein M, John R. Left bundle branch block revealing a primary small bowel carcinoid metastasizing to the interventricular septum. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2020;31(3):408-410.

-

Kahveci AS, Mubarak MF, Perveze I, Daglilar ES. Differential to Terminal Ileitis: Terminal Ileum Neuroendocrine Tumor Identified on Screening Colonoscopy. Ochsner J. 2023;23(1):67-71.

-

Polydorides AD, Liu Q. Evaluation of Pathologic Prognostic Factors in Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Small Intestine. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022;46(4):547-556.

-

Dawod M, Gordoa TA, Cives M, et al. Antiproliferative Systemic Therapies for Metastatic Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumours. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2021;22(8):73.

-

Cives M, Strosberg J, Al Diffalha S, Coppola D. Analysis of the immune landscape of small bowel neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26(1):119-130.

-

Koea J; Commonwealth Neuroendocrine Tumour Research Collaborative (CommNETs) Surgical Section. Management of Locally Advanced and Unresectable Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumours. World J Surg. 2021;45(1):219-224.

-

Kasai Y, Mahuron K, Hirose K, et al. Prognostic impact of a large mesenteric mass >2 cm in ileal neuroendocrine tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(8):1311-1317.

-

Horwitz JK, Marin ML, Warner RRP, Lookstein RA, Divino CM. EndoVascular Occlusion and Tumor Excision (EVOTE): a Hybrid Approach to Small-Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors with Mesenteric Metastases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23(9):1911-1916.

-

Bangla VG, Wolin EM, Kim MK, Divino CM. Resection Prolongs Overall Survival for Nonmetastatic Midgut Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors: A National Cancer Data Base Study. Pancreas. 2022;51(2):171-176.

-

Watanabe A, Mckendry G, Yip L, Loree JM, Stuart HC. Association between surveillance imaging and survival outcomes in small bowel neuroendocrine tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2023;127(4):578-586.

-

Draskacheva N, Saljamovski D, Gošić V, et al. When is surgery indicated in metastatic small intestine neuroendocrine tumor?. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(10):rjad580.

-

Wonn SM, Limbach KE, Pommier SJ, et al. Outcomes of cytoreductive operations for peritoneal carcinomatosis with or without liver cytoreduction in patients with small bowel neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2021;169(1):168-174.

-

Kaçmaz E, Chen JW, Tanis PJ, Nieveen van Dijkum EJM, Engelsman AF. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after surgical resection of small bowel neuroendocrine neoplasms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neuroendocrinol. 2021;33(8):e13008.

-

Hajjar R, Mercier F, Passot G, et al. Cytoreductive surgery with or without hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for small bowel neuroendocrine tumors with peritoneal metastasis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48(7):1626-1630.

-

Zaidi MY, Lopez-Aguiar AG, Dillhoff M, et al. Prognostic Role of Lymph Node Positivity and Number of Lymph Nodes Needed for Accurately Staging Small-Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(2):134-140.

-

Kaçmaz E, Slooter MD, Nieveen van Dijkum EJM, Tanis PJ, Engelsman AF. Fluorescence angiography guided resection of small bowel neuroendocrine neoplasms with mesenteric lymph node metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(7):1611-1615.

-

McGuinness MJ, Woodhouse B, Harmston C, et al. Survival of patients with small bowel neuroendocrine neoplasms in Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92(7-8):1748-1753.

-

Pino A, Frattini F, Ieni A, et al. Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors: Focus on Pathologic Aspects and Controversial Surgical Issues. Curr Surg Rep. 2022;10:160–171.

-

Dapri G, Bascombe NA. Three trocars laparoscopic right ileocolectomy for advanced small bowel neuroendocrine tumor. Surg Oncol. 2019;28:76-77.

-

Wong W, Perez Holquin RA, Stahl KA, et al. Predictors and Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Surgery for Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors: Minimally Invasive Surgery for SBNETs. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2022;26(6):1252–1265.

-

Rajaretnam NS, Meyer-Rochow GY; Commonwealth Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Collaborative (CommNETs) Surgical Section. Surgical Management of Primary Small Bowel NET Presenting Acutely with Obstruction or Perforation. World J Surg. 2021;45(1):203-207.

-

Lucandri G, Fiori G, Lucchese S, et al. Extended surgical resection for nonfunctioning duodenal neuroendocrine tumor. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022(9):rjac391.

-

Xie J, Zhang Y, He M, Liu X, Xie P, Pang Y. Survival comparison between endoscopic and surgical resection for non-ampullary duodenal neuroendocrine tumor (1–2 cm). Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):15339.

-

Tran CG, Sherman SK, Suraju MO, et al. Management of Duodenal Neuroendocrine Tumors: Surgical versus Endoscopic Mucosal Resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29(1):75-84.

-

Gamboa AC, Liu Y, Lee RM, et al. Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors: Somewhere between the pancreas and small bowel?. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(8):1293-1301.

-

Kleinschmidt TK, Christein J. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: a case report, review and recommendations. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020(6):rjaa119.

-

Ziogas IA, Rallis KS, Tasoudis PT, Moris D, Schulick RD, Del Chiaro M. Management and outcomes of mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: A systematic review and pooled analysis of 56 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2023;49(4):682-687.

-

Yoshimachi S, Ohtsuka H, Aoki T, et al. Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater: a case report and literature review. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13(1):37-45.

-

Shimai S, Yamamoto K, Sofuni A, et al. Three Cases of Ampullary Neuroendocrine Tumor Treated by Endoscopic Papillectomy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Intern Med. 2020;59(19):2369-2374.

-

Lamarca A, Cives M, de Mestier L, et al. Advanced small-bowel well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours: An international survey of practice on 3rd-line treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(10):976-989.

-

Brighi N, Panzuto F, Modica R, et al. Biliary Stone Disease in Patients with Neuroendocrine Tumors Treated with Somatostatin Analogs: A Multicenter Study. Oncologist. 2020;25(3):259-265.

-

Rinzivillo M, Prosperi D, Bartolomei M, et al. Efficacy of Lutetium-Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Inducing Prolonged Tumour Regression in Small-Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumours: A Case of Favourable Response to Retreatment after Initial Objective Response. Oncol Res Treat. 2021;44(5):276-280.

-

Larouche V, Akirov A, Alshehri S, Ezzat S. Management of Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(9):1395.

-

Agarwal P, Mohamed A. Systemic Therapy of Advanced Well-differentiated Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors Progressive on Somatostatin Analogues. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2022;23(9):1233-1246.

-

Grillo F, Albertelli M, Malandrino P, et al. Prognostic Effect of Lymph Node Metastases and Mesenteric Deposits in Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Small Bowel. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(12):3209-3221.

-

Symons R, Daly D, Gandy R, Goldstein D, Aghmesheh M. Progress in the Treatment of Small Intestine Cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2023;24(4):241-261.

-

Gupta A, Lubner MG, Liu JB, Richards ES, Pickhardt PJ. Small bowel neuroendocrine neoplasm: what surgeons want to know. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47(12):4005-4015.

-

Acosta LF, Chacon E, Eman P, Dugan A, Davenport D, Gedaly R. Risk of Infectious Complications After Simultaneous Gastrointestinal and Liver Resections for Neuroendocrine Tumor Metastases. J Surg Res. 2019;235:244-249.

-

Hallet J, Law C; Commonwealth Neuroendocrine Tumours Research Collaborative (CommNETs) Surgical Section. Role of Primary Tumor Resection for Metastatic Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. World J Surg. 2021;45(1):213-218.

-

Gangi A, Anaya DA. Surgical Principles in the Management of Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(11):88.

-

Bennett S, Coburn N, Law C, et al. Upfront Small Bowel Resection for Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors With Synchronous Metastases: A Propensity-score Matched Comparative Population-based Analysis. Ann Surg. 2022;276(5):e450-e458.

-

Raphael MJ, Chan DL, Law C, Singh S. Principles of diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumours. CMAJ. 2017;189(10):E398-E404.

-

Al-Toubah T, Morse B, Strosberg J. Efficacy of Capecitabine and Temozolomide in Small Bowel (Midgut) Neuroendocrine Tumors. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(2):510-515.

-

Liu Q, Polydorides AD. Diagnosis and prognostic significance of extramural venous invasion in neuroendocrine tumors of the small intestine. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(11):2318-2329.

-

Manguso N, Nissen N, Hendifar A, et al. Prognostic factors influencing survival in small bowel neuroendocrine tumor with liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(6):926-931.

-

Sherman SK, Maxwell JE, O’Dorisio MS, O’Dorisio TM, Howe JR. Pancreastatin predicts survival in neuroendocrine tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(9):2971-2980.

-

Woltering EA, Voros BA, Beyer DT, et al. Plasma Pancreastatin Predicts the Outcome of Surgical Cytoreduction in Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Small Bowel. Pancreas. 2019;48(3):356-362.

-

Progression of Advanced Small-Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors After Multimodal Surgical Therapy - The ASCO Post. Accessed: Nov. 19, 2023. [Online]. https://ascopost.com/news/april-2020/progression-of-advanced-small-bowel-neuroendocrine-tumors-after-multimodal-surgical-therapy/

-

Chatani PD, Aversa JG, McDonald JD, Khan TM, Keutgen XM, Nilubol N. Preoperative serum chromogranin-a is predictive of survival in locoregional jejuno-ileal small bowel neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2021;170(1):106-113.

-

Hiltunen N, Rintala J, Väyrynen JP, et al. Monocarboxylate Transporters 1 and 4 and Prognosis in Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(10):2552.

-

Alfagih A, AlJassim A, Alqahtani N, Vickers M, Goodwin R, Asmis T. Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors-10-Year Experience of the Ottawa Hospital (TOH). Curr Oncol. 2023;30(8):7508-7519.

-

Karppinen N, Lindén R, Sintonen H, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Small Intestine Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2018;107(4):366-374.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Importanţa testării genetice în cancer

În momentul de față, testele genetice au devenit o parte importantă și necesară din algoritmul de diagnostic și tratament al cancerului.

Clasificarea moleculară a cancerelor colorectale şi importanţa ei clinică - scurt review

Cancerul colorectal (CRC) reprezintă unul dintre cele mai frecvente tipuri de cancer, fiind caracterizat de alterarea căilor critice, cum ar fi: WN...

Multiparametric MRI with gadoxetic acid (Primovist®) in oncological patients: current indications and utility of the hepatobiliary phase

Acidul gadoxetic, sau Gd-EOB-DTPA (Primovist®), este un agent de contrast T1-pozitiv, hepatospecific, utilizat în imagistica prin rezonanţă magneti...

Câteva instrumente necesare în practica îngrijirilor paliative din oncologia medicală

Îngrijirile paliative sunt o parte integrantă din cadrul îngrijirilor pacienţilor oncologici. De multe ori se face o confuzie între îngriji...