During their careers, the oncologists or palliative care physicians will have been confronted at least once with patients with substance use disorders. Addiction was defined by a consensus of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society and American Society of the Addiction Medicine as a “primary, chronic, neurobiologic disease, with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviours that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving”(1). Cross addiction represents the substitution of one addiction with another, and we suspected this phenomenon in the case of our patient, N.M., presented in this article. The patient whom we refer to in this article is a young man diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma and, during treatment for cancer, he has developed an addiction and a co-addiction to opioids, benzodiazepines, alcohol and muscle relaxants.

Dependența încrucișată - prezentare de caz

Cross addiction - a case presentation

First published: 04 aprilie 2017

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/OnHe.38.1.2017.588

Abstract

Rezumat

Medicii oncologi sau de îngrijire paliativă întâlnesc nu o dată în cursul carierei lor pacienţi care au dezvoltat o adicţie sau o dependenţă psihică la diferite substanţe cum ar fi opioide sau benzodiazepine. Această problemă patologică se poate manifesta printr-o nevoie irezistibilă de a folosi substanţa în cauză (craving), pierderea controlului asupra utilizării acestei substanţe şi printr-un consum compulsiv, chiar dacă persoana devine conştientă de pierderile materiale, sociale, profesionale şi psihologice datorate acestui consum. Unii pacienţi pot să ajungă să schimbe o adicţie cu alta, cum ar fi, de exemplu, alcoolul cu benzodiazepine, sau cocaina cu amfetamine, sau un drog cu un comportament patologic cum ar fi jocurile de noroc. Pacientul la care ne referim în acest articol este un tânăr diagnosticat cu limfom Hodgkin şi care, în cursul tratamentului pentru cancer, a dezvoltat o adicţie şi o coadicţie la opioide, benzodiazepine, alcool şi relaxante musculare.

Any oncologist is intimately involved in the struggles of his patients’ battling cancer and one of those struggles is often represented by the cancer or cancer treatment related pain. The oncologist and the palliative care physician are trained to respond to a patient’s reports of suffering related to pain or uncontrolled symptoms without wondering if the same patient has an alternative motive. The responses often center on words of encouragement, such as: “We are in this fight together and I will help you beat the cancer” or “I will keep you out of pain”.

Unfortunately, at least once in our careers we will discover that we “have been played” by some patients. We are disappointed, we feel hurt, but we move on because we believe we must trust our patients who are fighting cancer and need our help to get them out of pain as quickly as possible and for good.

The case we are presenting is about a young adult male, N.M., who taught us a difficult lesson while being under our care for nearly 2 years.

N.M. is a 24-year-old Caucasian male with a diagnosis of recurrent Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The treatment involved radiation to the lumbar area, several rounds of chemotherapy with agents such as doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) and gemcitabine and cisplatin followed by carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan (BEAM) conditioning with an autologous stem cell transplant.

His pain history started in early 2011, when he noticed low back pain with associated sciatica. He was managing it at the beginning with non-steroidal antiinflammatories (NSAIDs) and hydrocodone, but over the course of 6 months the pain became acutely more intense and one morning he woke up with bilateral lower extremity paralysis, numbness and incontinence. He was evaluated at a local hospital and found to have an enormous paraspinal mass with spinal cord impingement for which he underwent an emergency L3-L5 laminectomy. He fortunately recovered all of his motor functions, but he developed a chronic continuous pain that required opioids and he was referred to our Supportive Care Clinic.

His back pain had two components. The first component was described as a constant moderate to severe throbbing sensation over the lumbosacral spine that could be exacerbated by physical activity and certain body positions. The second component of the pain was described as a very sharp shooting sensation that radiates down his buttocks, and sometimes upward towards the thoracic spine. He denied having any associated numbness, weakness, urinary or fecal incontinence, or fevers associated with the pain.

N.M.’s pain was managed with various doses of several opioids such as immediate release hydrocodone, extended and immediate release morphine, immediate release hydromorphone, fentanyl patches and methadone. Some of these drugs were discontinued either because of lack of efficacy, or reported side effects, particularly nausea, or because of the coverage by his medical insurance. The only exception was oxycodone extended release that was discontinued at the patient’s request, who reported “feeling high” from it. He was prescribed the following co-analgesics: Gabapentin, oral NSAIDs when possible, ointments with NSAIDs or lidocaine, and muscle relaxants. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), massage and physical therapy were tried as well. He was also placed on an intrathecal pain pump, that was later removed because it was perceived as ineffective in controlling his pain and apparently caused an even greater numbness and neuropathic pain in his left leg.

At certain times, the patient admitted to taking 10 tablets of immediate release morphine 30 mg or hydromorphone 8 mg altogether, despite being counseled otherwise and informed multiple times of long-term opioid therapy side effects such as tolerance, dependency and addiction. The patient denied experiencing any euphoria, lightheadedness or any side effects whatsoever when taking that many pills of morphine or hydromorphone at a time. The patient also denied craving the opioids and consistently stated he takes pain medication just to relieve pain.

The PDMP (Prescription Drugs Monitoring Program) reports consistently showed the patient receiving prescriptions only from City of Hope providers. We were reassured that he was not “doctor shopping” and he was compliant with our clinic’s rules and the opioid agreement that he has signed. The PDMP program called CURES in the state of California (Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System) represents a database of dispensed Schedule II, III and IV controlled substance prescriptions in an effort to reduce the prescription drug abuse and diversion without affecting legitimate medical practice or patient care.

His urine drug screens were always negative for illicit substances and positive for the opioids and benzodiazepines prescribed to him.

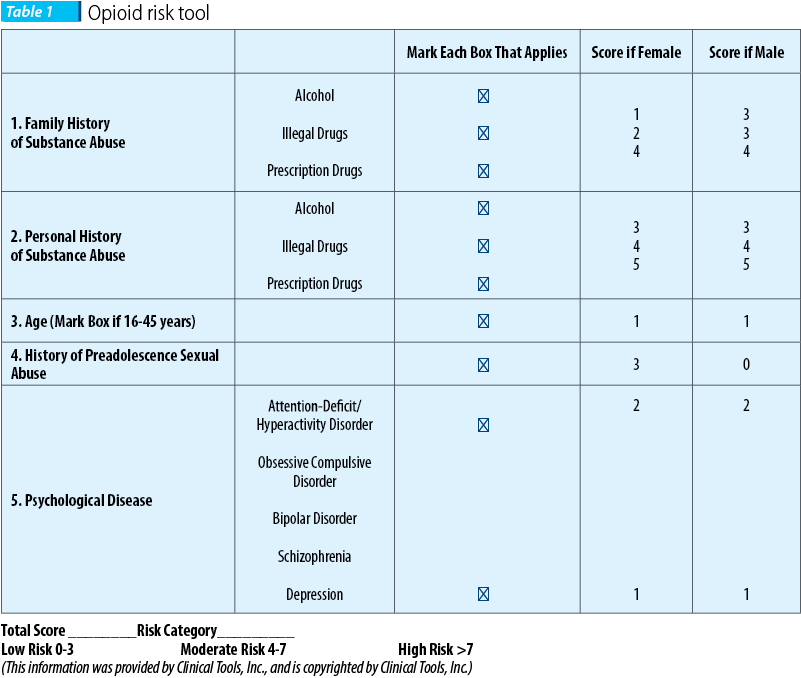

An Opioid Risk Tool (Table 1) was performed and the patient scored 3 based on his young age and a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder as a child. This score put him at a mild to moderate risk for developing addiction to opioids and benzodiazepines.

Several differential diagnoses attempting to explain his compulsive behavior towards opioids such as opioid-induced hyperalgesia, pseudoaddiction, diversion or a substance use/abuse disorder were all entertained.

About one year after being in our care, the patient agreed to an opioid detoxification because he wanted to get a job as an electrician or possibly as a civilian employee in the military.

A plan to wean him off opioids was put in place that involved the services of an addiction medicine specialist. Several months later and after a few setbacks the patient was opioid-free and experiencing the same or even less pain. During this time he reported the need to go to the local emergency room with increased pain possibly related to voluntary opioid abstinent withdrawal, but he always declined opioids.

Only a few months later, his parents shared that N.M. was using 12-14 mg of Alprazolam daily obtained from various sources: physicians, family, friends, and possibly from the streets. Our clinic was also prescribing him Lorazepam 2-3 mg per day for anxiety.

Extensive counseling, emotional support and consultants from multiple disciplines were again involved to help the patient cope with his anxiety and compulsive use of benzodiazepines that N.M. slowly managed to decrease by more than a half his average daily dose after he had been placed on Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs), and anticonvulsants amongst others.

Unfortunately, during this time period the patient started using high quantities of alcohol. He admitted to consuming half to a full bottle of whiskey or vodka. He also began making desperate phone calls to multiple prescribers asking for muscle relaxants that he was using in high quantities, well above the maximum recommended daily dose.

A diagnosis of cross addiction was suspected at this time and efforts were made to place the patient into a rehabilitation-detoxification unit.

The patient returned to see us after being discharged from the rehabilitation-detoxification unit when he reported being opioids, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants and alcohol free. Sadly, after this reunion, N.M. stopped all follow-ups with his clinicians, despite multiple efforts to contact him.

According to the American Society for Addiction Medicine (ASAM), addiction is defined as a “primary, chronic disease of the brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death”(2).

Addiction may occur in 3% to 26% of the general population, in 19% to 25% of the hospitalized patients and in 40% to even 60% of patients who have sustained a major trauma(3).

Cross addiction represents the substitution of one addiction with another. An example would be when an alcoholic trades alcohol for benzodiazepines or a cocaine addict trades cocaine for amphetamines or alcohol. N.M. is a perfect example of cross addiction. He traded opioids for benzodiazepines, then for alcohol and muscle relaxers, to ultimately relapse again to benzodiazepines and opioids. And the list of examples may go on and on.

Many addicts have a “drug of choice” that brings them the most satisfaction(3). Their decision to abstain from using this drug of choice is commendable because they finally realize they have a problem; however, many such patients enter the danger zone when they think it is okay to use a substance as long as it is not their drug of choice. They may say it is okay to use marijuana as long as it is not alcohol or alcohol as long it is not cocaine. And using benzodiazepines or opioids instead of alcohol for example gives them an even better excuse: “It was prescribed by my doctor who is very smart; ergo, it is okay to use it”.

Regrettably, cross addiction cannot be isolated solely to drugs. Dangerous behaviors such as sex addiction, pathological gambling, overspending, eating disorders, or computer games could lead to the same problem. A study by Griffiths showed that such cross addictions tends to occur in adults and adolescents, predominantly involving males, and was associated with gambling and alcohol(4).

The outcome for some of these patients is a circling back to their drug or behavior of choice.

Literature review attributes a high risk of developing cross addiction to:

1. Psychiatric disorders. Many such patients suffer from a dual diagnosis when addiction coexists with mental illness. They may also elicit impulsive-compulsive behaviors(5) or suffer from a cluster B personality disorder(6).

2. Recent recovery. The further away one is in the addiction treatment, the better the outcome; however, the risk remains high as acknowledged by Alcoholic Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous as the 13th step when patients replace their “drug of choice” with another substance or behavior with the same addictive potential(5).

3. Male gender(6).

4. Unmarried individuals(6).

5. Substance abuse started at a young age(6).

6. Poor parental supervision, delinquency or other sociodemographic risk factors such as poverty or peer groups(7).

Clinicians could intervene by:

1. Taking a thorough social and addiction history using a nonjudgmental attitude, as patients may feel less inclined to open up if they sense they are being judged.

2. Educating and counseling the patients of the risks of addiction or cross addiction and avoid minimizing the risk of addiction of the “more acceptable “drugs or behaviors such as tobacco, alcohol, overexertion, or overeating(5).

3. Providing medical management of withdrawal symptoms, psychiatric disorders, or any complications of addiction.

4. Providing psychological assistance throughout treatment and relapse, knowing that about 80 to 90% of the patients will relapse during the first year after treatment(7).

5. Immediate interventions in conjunction with the patient and/or his family in the case of a suspected relapse.

Going back to our patient, last year we received a phone call on our triage line about a City of Hope patient who was homeless, living in a truck that was not operational, and filled with empty alcohol bottles. The patient was identified as N.M. We contacted his parents and ex-girlfriend, but they all declined to intervene. When a phone call was made to the patient, he reaffirmed his intentions of not returning to our institution and asked for money and prescriptions for opioids and benzodiazepines. And we realized he circled back.

The authors would like to clarify they do not consider themselves experts in the field of addiction medicine, and just wanted to share this learning experience with their colleagues.

Bibliografie

2. American Society of Addiction Medicine – http://www.asam.org/quality-practice/definition-of-addiction

3. Seddon Savage, Assessment for addiction in pain-treatment settings, Clinical Journal of Pain, vol. 18, No 4, Supplement 2002 PMID:12479252.

4. Mark Griffiths, An exploratory study of gambling cross addictions, Journal of Gambling Studies, 1994, Dec; 10(4):371-84, doi: 10.1007/BF02104903.

5. Kathryn McFadden, Cross-Addiction: From Morbid Obesity to Substance Abuse – Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care, Volume 5, Number 2, 2010.

6. Carlos Blanco, Mayumi Okuda, Shuai Wang, Shang-Min Liu, Mark Olfson, Testing the drug substitution switching-addictions hypothesis. A prospective study in a nationally representative sample, JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Nov; 71(11):1246-53. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1206.

7. Howard Shaffer, Debi LaPlante, Richard LaBrie, Rachel Kidman, Anthony Donato, Michael Stanton, Toward a Syndrome Model of Addiction: Multiple Expressions, Common Etiology, Harvard Review of Psychiatry, November/December 2004, 12(6):367-74, doi: 10.1080/10673220490905705.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Flexibilitatea uimitorului lambou Limberg

Lamboul Limberg – sau „lamboul uimitor Limberg” – este un lambou de transpunere extrem de flexibil, bazat pe circulaţia aleatorie. Acesta este p...

Can we achieve successfully local control by IMRT radiotherapy in the treatment of male breast cancer? A case report

Această prezentare descrie un caz rar de cancer mamar la un pacient de gen masculin, patologie care are o incidenţă mai mică de 1% din toate cazur...