Nontraumatic splenic emergencies in onco-hematological pathology: what is important to know in CT evaluation?

Urgenţe splenice în patologia oncohematologică: ce este important de ştiut în evaluarea CT?

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to present and illustrate the computed tomography (CT) findings of splenic emergencies – vascular and infectious – encountered in hematologic malignancies, based on a selection of cases. The CT aspects were classified in vascular – hemorrhagic and ischemic – splenic lesions and infectious (abscesses) lesions. CT evaluation plays a crucial role in the diagnosis of acute splenic lesions in patients with hematologic malignancies.Keywords

nontraumatic splenic emergenciesoncohematological patientsCT findingsRezumat

Scopul acestui articol este de a prezenta şi ilustra aspectele computer-tomografice (CT) înâlnite în urgenţele splenice – vasculare şi infecţioase – în contextul afecţiunilor hematologice maligne, pe baza unei selecţii de cazuri. Aspectele CT au fost clasificate în leziuni splenice vasculare – hemoragice şi ischemice – şi leziuni infecţioase (abcese). Evaluarea CT joacă un rol crucial în diagnosticul leziunilor splenice acute la pacienţii cu afecţiuni hematologice maligne.Cuvinte Cheie

urgenţe splenice nontraumaticepacienţi oncohematologiciaspecte CTIntroduction

The “forgotten organ” – how is spleen considered, because it is frequently ignored by the clinician – may become an acute condition in onco-hematological patients. In this article, we present, illustrate and discuss the computed tomography (CT) findings of nontraumatic splenic emergencies in onco-hematological patients. About 1% of patients who were explored by computed tomography for the clinical suspicion of acute abdomen had incidental splenic lesions(1-3). The onco-hematologic patient may have complications of the underlying disease such as hemorrhagic or ischemic splenic lesions, as well as infectious due to immunosuppression or cytostatic therapy(4,10). There are few data in the literature about these complications.

CT protocol

The CT evaluation includes a three-phase protocol: nonenhanced CT (NECT), useful for the detection of fresh hemorrhage, air, calcifications, pure fluid or lipomatous content; contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) in arterial phase (30-35 seconds after the onset of the i.v. injection), and late enhancement phase (splenic parenchymal phase which begins 60 to 90 seconds after the start of the injection)(1-3). Postprocessing comprise multiplanar reconstruction (MPR), maximum intensity projection reconstruction (MIP), or volumetric rendering technique (VRT).

CT findings

Vascular splenic lesions

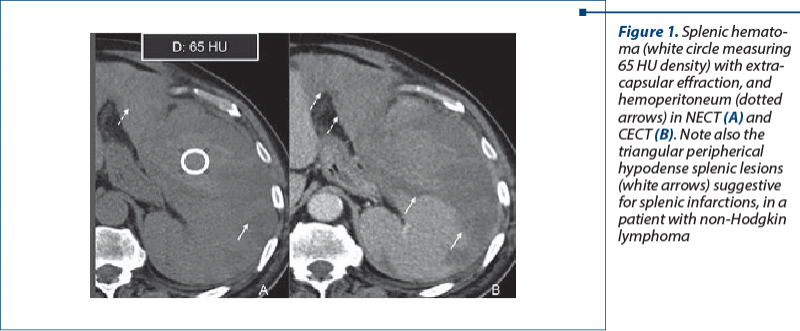

1. Nontraumatic hemorrhagic involving the spleen may be secondary to splenic rupture or to the anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy(2-4). In some cases, the hematoma can be self-limited, but in splenic active hemorrhage or rupture, the diagnosis and treatment are urgent, therefore CT is the best imaging modality to perform, revealing a hyperdense intraparenchymal and/or perisplenic accumulation with a specific density in favor of acute hematoma: 60-80 HU (Figure 1).

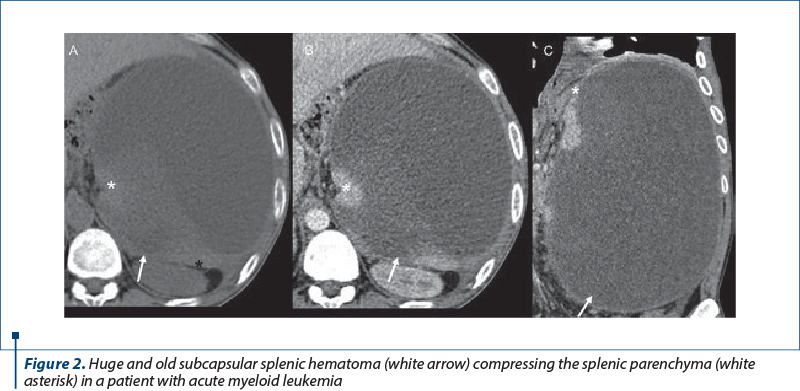

Sentinel clot sign may be present: highest density blood adjacent to spleen. A very high attenuation (similar in density to that of injected contrast material in the arteries) within or surrounding the spleen raises the suspicion for an active bleeding(5-8). Mass effect may be present in large subcapsular splenic hematomas(9) (Figure 2).

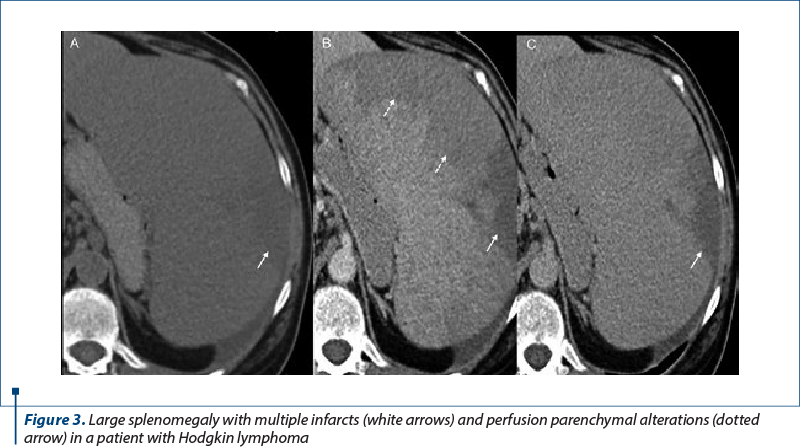

2. Ischemic disorders. Splenic infarction is a rare cause of abdominal pain, even though the prevalence is unknown. The incidence of thrombotic events is influenced by the type and the stage of the disease, by antitumoral therapy and by the widely used central venous catheters. Ischemic complications are due to perfusion defects followed by splenic infarction. Necrosis is the result of arterial or venous occlusion. Some publications proved a higher risk of thrombosis in patients with lymphoma, multiple myeloma or acute leukemia, in recently diagnosed patients or in patients undergoing chemotherapy(3,4,10,11).

Patients with onco-hematological disorders can present fever and left upper quadrant pain, although a significant percentage of patients with splenic infarcts may remain asymptomatic with incidental discovery in CT evaluation. Splenic infarcts appear in CT as irregular or wedge-shaped low attenuation areas with the apex targeted to hilum and the base positioned to the capsule that do not enhance with contrast (Figure 3).

Complications of splenic infarcts include abscess formation, hemorrhage and, rarely, splenic rupture in the case of massive infarcts(3,4).

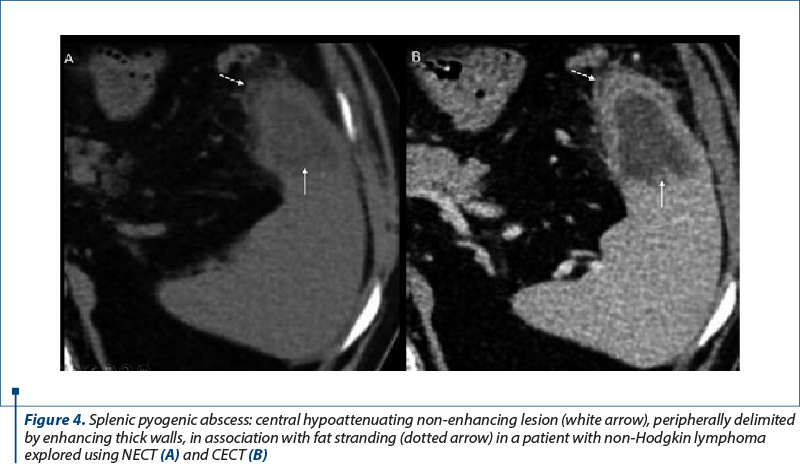

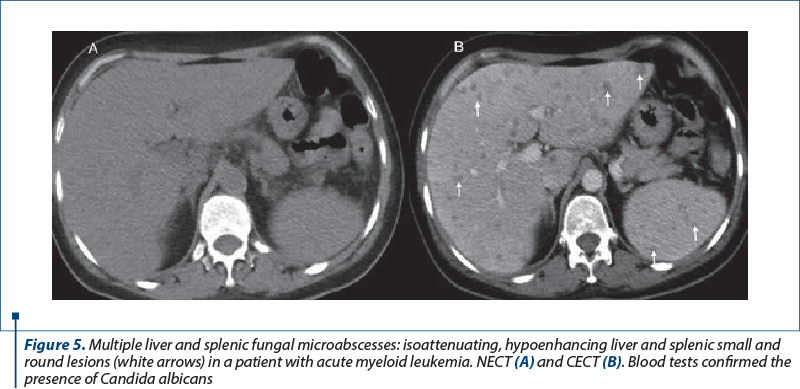

3. Splenic abscess. Neutropenia, altered B-cell and splenic functions predispose to a high risk of severe infections. Often, immunocompromised patients develop multiorgan abscesses, either of bacterial or fungal etiology. Splenic pyogenic abscesses are predominantly due to hematogenous spread of infection(1-4). They can be solitary, multiple, or multilocular. In CT, they are hypoattenuating, with no or moderate enhancement, and they can be encapsulated, with a peripheral enhancing rim (Figure 4).

In their evolution, they can progress to complex gas or fluid-filled content. In immunocompromised patients, splenic fungal microabscesses present as small (<10 mm), multiple, rounded, focal splenic hypoenhancing lesions associated with splenomegaly(11,12).

The CT structured report must contain: dimension, shape and contours of the spleen; a detailed description of splenic/perisplenic lesion(s): localization, number, shape, contour/outline, structure of the lesion, density-attenuation (delineation between hemorrhagic, cystic, air, or tissular lesions); pattern of contrast enhancement, effraction in active bleeding; other incidental lesions involving abdominal viscera; permeability of the abdominal vessels; lymph node enlargement; ascites or pleural effusion; bones lesions; anatomical variants.

Conclusions

Splenic complications developed in onco-hematologic patients – such as abscess, infarction or hemorrhage – are life-threatening and require an urgent diagnosis and treatment. Computed tomography is the best imaging tool to diagnose splenic emergencies lesions, providing criteria to choose between surgical or medical management in a multidisciplinary team approach. The interpretation of the CT exam should take into account all of the essential elements needed for making a correct diagnosis, such as the actual clinical content, laboratory data and patients’ antecedents.

Corresponding author: Ioana G. Lupescu E-mail: ilupescu@gmail.com

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY licence.

Bibliografie

-

Thut D, Smolinski S, Morrow M, et al. A diagnostic approach to splenic lesions. Applied Radiology. 2017;46(2):7-22.

-

De Schepper AMF. Vanhoenacker F. Medical imaging of the spleen. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2000. ISBN 978-3-642-57045-2 (eBook).

-

Prokop M, Galanski M, van Der Molen AJ. Spiral and Multislice Computed Tomography of the Body. 1st Ed., Thieme, 2003.

-

Saboo SS, Krajewski KM, O’Regan KN, et al. Spleen in haematological malignancies: spectrum of imaging findings. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1009):81-92.

-

Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1114–21.

-

McKenzie CV, Colonne CK, Yeo JH, Fraser ST. Splenomegaly: Pathophysiological bases and therapeutic options. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;94:40-43.

-

Gedik E, Girgin S, Aldemir M, et al. Non-traumatic splenic rupture: report of seven cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterolology. 2008;14(43):6711–6716.

-

Kocael P, Simsek O, Bilgin I, et al. Characteristics of Patients with Spontaneous Splenic Rupture. Int Surg. 2014;99(6):714–718.

-

Barrak D, Ramly EP, Chouillard E, Khoury M. Chronic spontaneous idiopathic spleen hematoma presenting as a large cystic tumor: a case report with review of the literature. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;2014(6):rju060.

-

Voicovici A, Dijmarescu A, Preda EM, Dumitrescu C, Lupescu IG. Splenic lesions in hematologic malignancies: a challenge of imaging diagnosis or not? ECR 2019. 10.26044/ecr2019/C-3212.

-

Colombo R, Gallipoli P, Castelli R. Thrombosis and hemostatic abnormalities in hematological malignancies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14(6):441-450.

-

Pfaffenbach B, Donhuijsen K, Pahnke J, et al. Systemische Pilzinfektionen bei hämatologischen Neoplasien. Eine Autopsiestudie an 1053 Patienten [Systemic fungal infections in hematologic neoplasms. An autopsy study of 1,053 patients]. Med Klin (Munich). 1994;89(6):299-304.