Breast and ovarian cancer are relatively frequent malignancies in BRCA mutation carrier patients. The synchronous presence of these two cancers is a challenging clinical situation, especially in young women. We present a case report of a young woman diagnosed with high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma, somatic BRCA-mutant, who developed breast cancer during PARP inhibitor treatment. The right treatment choice for both malignancies may be equally thought-provoking for patient and doctor in face of recurrence risk reduction endpoint. This case report emphasizes real life progression-free survival on PARP inhibitor treatment higher than in phase III clinical trials.

Second primary breast cancer during PARP inhibitor treatment of somatic BRCA mutant ovarian cancer – a case report

Cancer mamar apărut în timpul tratamentului cu inhibitori PARP pentru un cancer ovarian cu mutaţie BRCA somatică – prezentare de caz

First published: 31 mai 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/OnHe.63.2.2023.8091

Abstract

Rezumat

Cancerul mamar şi cel ovarian sunt neoplazii relativ frecvente la pacientele purtătoare de mutaţie BRCA. Prezenţa sincronă a acestor două tipuri de cancer este o situaţie clinică dificilă, în special la femeile tinere. Prezentăm un raport de caz al unei tinere femei diagnosticate cu carcinom ovarian seros de grad înalt, cu mutaţie BRCA somatică, care a dezvoltat şi cancer de sân în timpul tratamentului cu inhibitor PARP. Alegerea corectă a tratamentului pentru ambele tumori maligne poate fi la fel de provocatoare atât pentru pacient, cât şi pentru medic, în faţa obiectivului final de reducere a riscului de recurenţă a bolii. Acest raport de caz subliniază supravieţuirea fără progresia bolii mai îndelungată cu tratament cu inhibitor PARP în viaţa reală faţă de timpul raportat în studiile clinice randomizate de fază III.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth cause of death by cancer in the female population from Romania(1). Mutations in the BRCA1 (breast cancer gene 1) and BRCA2 (breast cancer gene 2) lead to an increased risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer as part of hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndrome(2). An additional risk is also present in non-hereditary, sporadic tumors since a proportion of ovarian and breast cancer tumors contain somatic (tumor only) BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants(3,4). There is a reported risk of second primary breast cancer after ovarian cancer(5) and, furthermore, it is suggested that second primary cancer has a specific dependency on the first primary cancer(6).

Case report

A 41-year-old woman presented to our hospital for diffuse abdominal pain for several days, dyspnea, meteorism and increased abdomen girth, on 16 October 2017. She did not have an underlying disease and she was a former smoker (40 package index years). Her menarche was at the age of 13 years old, with regular menstrual cycle and no history of pregnancy. The family history on maternal side revealed that her mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer, her aunt with ovarian cancer, and her uncle with gastric cancer. She had no evidence of menorrhagia or dysmenorrhea, and no painful defecation or dyspareunia. The laboratory analyses indicated an elevated level of serum tumor marker carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA-125) of 484.2 U/mL (normal range: 0-35 U/mL). Transvaginal ultrasonography revealed suspicious multifocal mass with mixed cystic and solid components measuring more than 30 mm in size in the right adnexa and more than 50 mm in size in the left adnexa and ascites fluid. Computed tomography scan confirmed the increased volume and the inhomogeneous structure with iodophilic tissue areas and non-iodophilic liquid density areas of both ovaries, along with a large amount of ascites fluid.

The patient decided to go for surgical treatment to Kent Hospital, Turkey. Positron-emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) scan was carried out before surgery and revealed widespread peritoneal fluid in the abdomen, filling the peritoneal recesses, hypermetabolic omental cake observed in transverse colon ventral (SUV=8), considered to be linked to peritonitis carcinomatosis, a mass lesion of 38/30 mm containing cystic or solid cystic components in the right ovary lodge and another one in the hypermetabolic (SUV=4.3) left lodge of 53/45 mm. One of the lesions was considered to be primary, while the other had metastatic characteristic. On 31 October 2017, radical surgery using laparotomy was performed. Radical hysterectomy type 3+, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (tumoral mass) debulking, total omentectomy, splenectomy, total visceral, parietal peritonectomy and pelvic paraaortic lymph node dissection were performed, without complications, and pneumococcal vaccine was injected. Optimal debulking cytoreductive surgery was performed successfully. The histopathological examination of the excised specimens showed bilateral high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) with invasion of the uterine serous, bilateral parameters, bilateral tubes, pelvic and upper abdominal peritoneum, transverse colon, fundic bladder, sigmoid colon, spleen capsule, omentum, diaphragm, positive ascites cytology, two pelvic lymph nodes were invaded and none paraaortic. The immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed using antibodies against Wilms’ tumor-1 (WT-1), estrogen receptor (ER), p53, and revealed that the ovarian tumors were negative for WT-1, positive for ER, positive for p53, and negative for calretinin. There was proof of lymphatic invasion, but no vascular or perineural spread. The final staging was stage IVA bilateral HGSOC (TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO]).

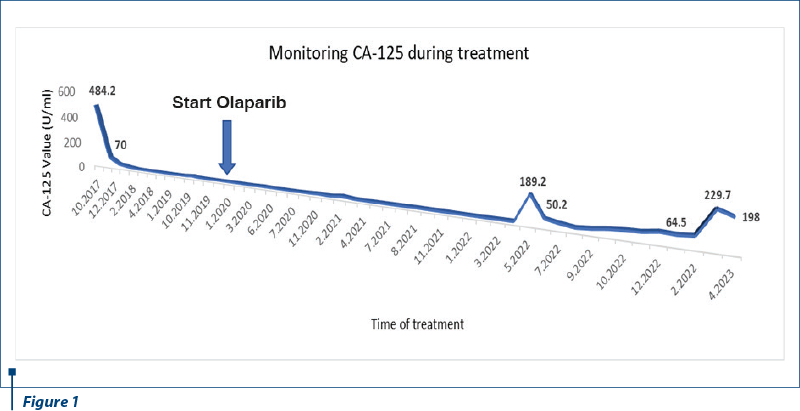

On 22 November 2017, adjuvant chemotherapy (CHT) with paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC 5-6) every 21 days was initiated and administered for six cycles, according to the multidisciplinary commission decision in our hospital. The imaging evaluation after adjuvant chemotherapy indicated no evidence of relapse. The level of serum CA-125 was increased before CHT (70 U/ml) and normalized during the treatment. Genetic testing for BRCA1/2 variants identified somatic BRCA1 mutation. Regular imaging and biochemical follow-up proved disease-free survival for 16 months, until September 2019, when magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed four subcapsular liver lesions and peritoneal carcinomatosis. First-line treatment for metastatic HGSC ovarian cancer platinum-sensitive was started with platinum-based combination therapy (with gemcitabine), every 21 days, for four cycles, with a relatively good tolerance, but biochemical hepatic cytolysis syndrome, evidenced by the increase of aspartate and alanine aminotransferase over 3-5 x ULN (upper limit of normal range). This liver toxicity was classified as grade 2 Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) and chemotherapy was uninterruptedly continued. Partial response was achieved after CHT and entitled maintenance therapy with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib, from 16 January 2020. Consistent PET-CT and MRI surveillance (at three to six months) besides monitoring serum CA-125 biomarker (monthly) were completed and provided evidence of progression-free survival (PFS) for 27 months.

In March 2022, the MRI discovered a new lesion on diaphragmatic capsule of the liver, suggesting peritoneal metastasis. Bilateral mammography identified a small nodule in the right breast, oncologically suspicious in the clinical context of the patient. On 25 April 2022, in Kent Hospital, Turkey, surgery was performed for right breast nodule and peritoneal metastasis. Right breast conservative surgery and axillary sentinel lymph node dissection were performed. The histopathological report identified invasive ductal carcinoma, moderately differentiated, in 30% of the tumor, and ductal carcinoma in situ in 70%, respectively, no lymph vascular (LV0) or perineural invasion (Pn0), and no tumor involvement of the surgical margin (R0). IHC revealed estrogen receptor status positive 100%, progesterone receptor status positive 50%, HER2/NEU equivocal (2+), and proliferation index (Ki67) 65%. The final stage of breast cancer was pT1c pN0 (sn) (TNM Classification) luminal B HER2-negative. The peritoneal diaphragmatic metastasis was removed and proved to be HGSOC relapse, with proliferation index (Ki67) 85%. For the secondary breast cancer, the patient refused to be treated with chemotherapy. Adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) to the whole right breast (total dose of 50 Gy in 25 fractions) and RT boost (total dose of 10 Gy in five fractions) to the tumor bed cavity were done, being well tolerated. The patient continued the treatment with PARP inhibitor, olaparib 300 mg, twice daily, and adjuvant endocrine therapy, aromatase inhibitor, anastrozole 1 mg once daily. After surgery, there was an increase of serum CA-125 biomarker up to 189.50 U/ml, steadily decreasing afterwards. The imaging relapse and biomarker increase were not related. The dynamic of CA-125 values is presented in Figure 1.

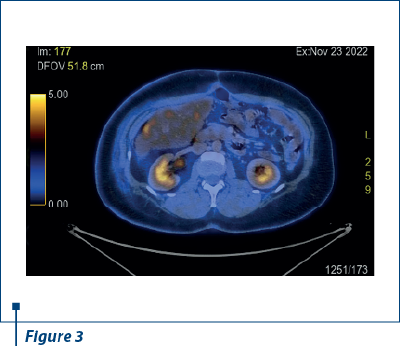

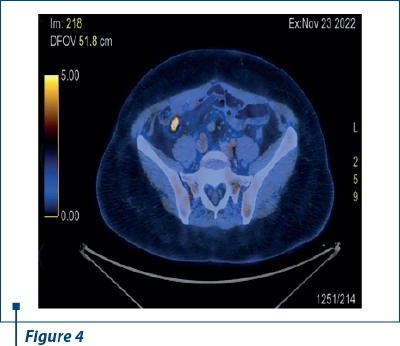

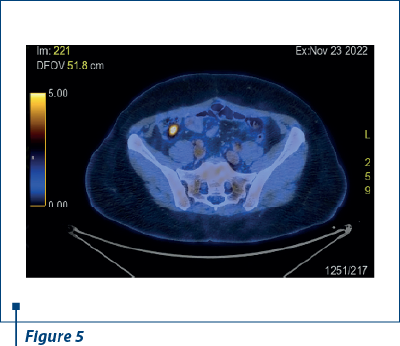

In 23 November 2022, after another nine months of PFS, PET-CT scan reported a small active metabolic focus located the liver and the diaphragm, on the surgical incision line (SUV=4), probably with postoperative inflammatory substrate, exemplified in Figures 2 and 3. PET-CT described also a new peritoneal pararectal pelvic lesion on the right side, in close contact to the mesorecta fascia, of 17.5/16.5 mm in dimension and hypermetabolic activity (SUV=15.04), suggesting a peritoneal metastasis, as shown in Figures 4 and 5. On 14 December 2022, in Kent Hospital, Turkey, surgical reintervention was performed for peritoneal tumor relapse and the suspicious lesion was excised along with right peritoneal biopsies and right obturator lymphatic nodes. The histopathological report showed no evidence of tumor relapse. CA-125 had an increased value (64.5 U/ml) at the time of surgery and remained at the same level during the next few months.

In March 2023, the serum CA-125 biomarker increased dramatically (229.7 U/ml) and the CT scan revealed a growth volume (30/27 mm to 17.5/16.5 mm in November 2022) of the same peritoneal node that was surgically removed four months before. Bilateral mammography presented no breast cancer local relapse. In 12 April 2023, CA-125 decreased spontaneously (at 198 U/ml) and the patient interrupted PARP inhibitor treatment for a period of 52 months, with an overall survival (OS) of 78 months. More imaging data are needed for the next therapeutic decision.

Discussion

We described a case report of a young woman diagnosed and treated for stage IVA HGSOC. She had several risk factors for ovarian cancer (such as no pregnancy, family history of breast and ovarian cancer, and BRCA1 somatic mutation)(7). As HGSOC is more aggressive and disseminate early within the abdominal cavity, optimal debulking cytoreductive surgery was performed to increase overall survival (OS) and PFS(8). Standard platinum-based combination adjuvant chemotherapy was administered according to actual guidelines, to reduce the significant risk of recurrence of stage IV HGSOC(9). The addition of bevacizumab to standard CHT was considered to bring no benefit on the overall survival for our patient, since optimal debulking was successfully performed(10). The initially increased serum CA-125 biomarker’s value before surgery dramatically dropped after surgery and during CHT, and remained stable. Serial measurement of serum CA-125 biomarker is a useful marker to assess the response of CHT according to Gynecological Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) criteria(11). As HGSOC in this patient was considered to be platinum-sensitive, a platinum-based combination was used for first line in recurrent HGSOC. Gemcitabine/carboplatin combination was relatively well tolerated. Hepatocytolysis syndrome grade 2 CTCAE(12) occurred during first-line CHT, but did not hold the treatment which continued for four cycles. According to OCEANS study, at that time of first relapse of platinum-sensitive disease ovarian cancer, bevacizumab might have been considered(13). The therapeutic decision balanced between adding bevacizumab to CHT and the maintenance therapy with PARP inhibitor. Being aware of exclusion criteria from Study 19(14) that did not allow maintenance olaparib immediately after CHT/bevacizumab combination and in the presence of BRCA mutation, we decided to challenge PARP inhibitor advantage. As the time of this medical decision was January 2020, the opportunity of bevacizumab/olaparib maintenance therapy was not available(15). Our patient reported enhanced PFS of 27 months, longer than published PFS in SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21 phase III trial of 19.1 months for platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and BRCA1/2 mutation patients(16). Moreover, this case report outcome confirmed PARP inhibitor benefit in somatic BRCA mutation patients(17).

After 27 months of PFS during olaparib monotherapy, oligometastatic relapse of HGSOC synchronously with secondary breast cancer stage IA (TNM) luminal B Her2-negative was surgically and histopathologically confirmed. Olaparib is also approved for use in first-line metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in germline BRCA-mutant patients(18). In this case, there was a somatic BRCA1 mutation and, theoretically, olaparib should have provided protection against the secondary breast cancer. Furthermore, the existing data evidenced bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy protection against breast cancer(19). Conversely, a recently published observational study reported low incidence of breast cancer after ovarian cancer in women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations(20). It was suggested that breast surveillance is better than risk-reducing surgical interventions. Another issue to be discussed in a BRCA1 mutation patient is prophylactic contralateral mastectomy. A large database identified a lack of benefit survival of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy(21). The risk of in-breast tumor recurrence after breast-conserving surgery was comparable among BRCA mutation carriers and non-carriers, especially in the context of prophylactic BSO and adjuvant systemic therapy(22). Single peritoneal relapse was considered to be oligometastatic disease and PARP inhibitor olaparib was continued, alongside adjuvant endocrine treatment for local ER-positive breast cancer. We did not have data to support this decision for olaparib maintenance, but patient’s refusal to be treated with CHT for breast cancer was an overwhelming argument in favor of PARP inhibitor maintenance. Taking into consideration breast cancer stage IA, there was no reason to perform mastectomy in this case. Adjuvant chemotherapy was discussed with the patient based on benefits and risk of recurrence(23) and the patient decided not to be treated with CHT. RT was completed according to guidelines(24). Oligometastatic relapse of HGSOC was not accompanied by serum CA-125 biomarker increase. More often, a rising CA-125 triggers further imaging, but here was not the case. This could be explained by an analysis performed in the SOLO2 study confirming that relying on CA-125 alone as part of surveillance in patients treated with maintenance olaparib is not enough(25). Almost half of the patients in SOLO2 without CA-125 progression had RECIST progression(26), and most of these patients had CA-125 values within the normal range, and that was exactly our case also. Regular CT scan should be considered rather than monitoring CA-125 alone, and in our patient, regular PET-CT and MRI were performed. It is even described, similarly with our case, that PET-CT was a valuable imaging method for surveillance and detection of recurrent ovarian cancer(27).

Conversely, an increase in serum CA-125 level recently occurred in conjunction with suspicious relapse on CT scan. The specificity of CA-125 for ovarian cancer is known to be poor and it can be increased in many benign conditions, such as pelvic inflammatory disease. Second opinion (performed in Kent Hospital, Turkey) on CT scan described a possible postoperatively organized seroma or lymphocele or hematoma. A spontaneous decrease in CA-125 level may be correlated to a benign lesion. Imaging evaluation should be performed for more detailed diagnostic. Which imaging modality would provide more useful information? PET-CT cannot accurately differentiate between benign and malignant lesions. MRI would provide detailed information for a surgical endpoint. There is a pertinent point to discuss at this moment the future potential options for treatment. In a relapse-free patient after surgery with histopathological evidence of non-metastatic disease, should olaparib be continued?

If not, which platinum-based combination would be preferred?

In this case report, we present a progression-free survival with olaparib of 27 months (the entire period of exposure to olaparib was 52 months) and an overall survival of 78 months, superior results than reported in the final analysis of SOLO2 study(28).

Conclusions

We have reported a case of HGSOC in a young woman with substantial genetic risk factors for both ovarian and breast cancer, who ultimately developed these two types of malignancies. Sequential best options therapies are fundamentally important to increase progression-free survival and overall survival.

Consequently, this case report highlights the challenges of daily medical practice in oncology and retrospectively thinking the effort of choosing the right therapy at the right moment from fewer possibilities in the past.

'

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY

Bibliografie

- Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer 2023. World Health Organization. Romania – Globocan 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-map.

- Sessa C, Balmaña J, Bober SL, et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Risk reduction and screening of cancer in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndromes: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(1):33-47. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.004.

- Talwar V, Rauthan A. BRCA mutations: Implications of genetic testing in ovarian cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2022;59 (Supplement); S56-S67. doi: 10.4103/ijc.IJC_1394_20.

- Toss A, Piombino C, Tenedini E, et al. The Prognostic and Predictive Role of Somatic BRCA Mutations in Ovarian Cancer: Results from a Multicenter Cohort Study. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(3):565. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11030565.

- Lim MC, Won YJ, Lim J, Salehi T, Yoo CW, Bristow RE. Second primary cancer after primary peritoneal, epithelial ovarian, and fallopian tubal cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):800. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4700-3.

- Tanjak P, Suktitipat B, Vorasan N, et al. Risks and cancer associations of metachronous and synchronous multiple primary cancers: a 25-year retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):1045. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-08766-9.

- Abraham J, Gulley LJ. The Bethesda Handbook of Clinical Oncology. Sixth Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW). Wolters Kluwer. Philadelphia, USA. 2023; 283-294.

- van der Burg ME, van Lent M, Buyse M, et al. The effect of debulking surgery after induction chemotherapy on the prognosis in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecological Cancer Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(10):629-34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321002.

- Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [published correction appears in Ann Oncol. 2018 Oct 1;29(Suppl 4):iv259]. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi24-vi32. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt333.

- Oza AM, Cook AD, Pfisterer J, et al. Standard chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer (ICON7): overall survival results of a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):928-36. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00086-8.

- Rustin GJ, Vergote I, Eisenhauer E, et al. Definitions for response and progression in ovarian cancer clinical trials incorporating RECIST 1.1 and CA 125 agreed by the Gynecological Cancer Intergroup (GCIG). Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(2):419-23. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182070f17.

- National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0. USA. Department of Health and Human Services. 2017. pp.15-17. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_50.

- Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2039-45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0505.

- Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(8):852-61. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70228-1.

- Harter P, Mouret-Reynier MA, Pignata S, et al. Efficacy of maintenance olaparib plus bevacizumab according to clinical risk in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer in the phase III PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;164(2):254-264. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.12.016.

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2017 Sep;18(9):e510]. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):1274-1284. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2.

- Poveda A, Lheureux S, Colombo N, et al. Olaparib maintenance monotherapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer patients without a germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation: OPINION primary analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;164(3):498-504. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.12.025.

- Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 26;377(17 ):1700]. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):523-533. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1706450.

- Eisen A, Lubinski J, Klijin J, et al. Breast cancer risk following bilateral oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: an international case-control study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(30):7491-6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7138.

- Safra T, Waissengrin B, Gerber D, et al. Breast cancer incidence in BRCA mutation carriers with ovarian cancer: A longitudal observational study. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;162(3):715-719. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.06.009.

- King TA, Sakr R, Patil S, et al. Clinical management factors contribute to the decision for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(16):2158-64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.4041.

- Evron E, Ben-David MA, Kaidar-Person O, Corn BW. Nonsurgical Options for Risk Reduction of Contralateral Breast Cancer in BRCA Mutation Carriers with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(5):964-969. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01609.

- Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, et al. Clinical Outcomes in Early Breast Cancer with a High 21-Gene Recurrence Score of 26 to 100 Assigned to Adjuvant Chemotherapy Plus Endocrine Therapy: A Secondary Analysis of the TAILORx Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(3):367-374. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.4794.

- Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [published correction appears in Ann Oncol. 2019 Oct 1;30(10):1674] [published correction appears in Ann Oncol. 2021 Feb;32(2):284]. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1194-1220. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdz173.

- Tjokrowidjaja A, Lee CK, Friedlander M, et al. Concordance between CA-125 and RECIST progression in patients with germline BRCA-mutated platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer treated in the SOLO2 trial with olaparib as maintenance therapy after response to chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2020;139:59-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.08.021.

- Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026.

- Bilici A, Ustaalioglu BBO, Seker M, et al. Clinical value of FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of suspected recurrent ovarian cancer: is there an impact of FDG PET/CT on patient management? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(7):1259-69. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1416-2.

- Poveda A, Floquet A, Ledermann JA, et al. SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21 investigators. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a final analysis of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):620-631. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00073-5.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Factori de prognostic în cancerul de sân triplu negativ

Cancerul de sân triplu negativ (CSTN) este o boală agresivă chiar și în stadiile inițiale. Există o rată de recidivă de 30% în primii 5 ani în stad...