Aim of the paper. The goal of this work is to outline the methods for regaining vocal, swallowing and respiratory function, based on the type of surgical intervention. Objective of the study. We present some therapeutic procedures for learning vocal, swallowing and breathing exercises. Materials and method. Patients admitted to the ENT Clinic in Craiova over a five-year period with laryngeal neoplasms underwent various surgical interventions, depending on tumor extension. Results. A total of 188 patients underwent surgical procedures, including total laryngectomies, partial laryngectomies (supraglottic horizontal, frontolateral, bicordocomissural) and cordectomies. Discussion. We studied the functional recovery possibilities for the patients’ group, assessing the preservation conditions and the vital function alterations. Patients chose various phonatory recovery procedures, either spontaneously, or through phoniatric exercises. Esophageal voice was achieved through logopedic exercises and, depending on motivation, ability or personal motivation, through tracheoesophageal prosthetic communication – the voice button. Conclusions. The oncologic surgical procedures on the larynx allow for functional recovery and socio-professional reintegration, even in the case of total laryngectomy.

Recovery of laryngectomized patients – work carried out in the ENT Clinic of the Craiova County Emergency Clinical Hospital

Recuperarea pacienţilor laringectomizaţi – rezultate obţinute în Clinica ORL a Spitalului Judeţean de Urgenţă Craiova

First published: 28 septembrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ORL.60.3.2023.8584

Abstract

Rezumat

Scopul lucrării. Această lucrare prezintă diferite modalităţi de a recăpăta funcţia vocală, de deglutiţie şi respiratorie, în funcţie de tipul de intervenţie chirurgicală. Obiectivele lucrării. Prezentăm unele procedee terapeutice de învăţare a exerciţiilor vocale, de deglutiţie şi respiraţie. Materiale şi metodă. Pacienţii internaţi în Clinica ORL Craiova, pe o perioadă de cinci ani, cu neoplasm laringian, au fost supuşi diverselor intervenţii chirurgicale, în funcţie de extensia tumorală. Rezultate. Un număr total de 188 de pacienţi au fost supuşi intervenţiilor chirurgicale, efectuându-se laringectomii totale, laringectomii parţiale (orizontală supraglotică, frontolaterală, bicordocomisurală) şi cordectomii. Discuţie. La lotul de pacienţi s-au studiat posibilităţile de recuperare funcţională, am urmărit condiţiile de conservare şi alterarea funcţiilor vitale. Diversele procedee de recuperare fonatorie au fost alese de către pacienţi fie spontan, fie prin exerciţiile foniatrice. Vocea esofagiană se realizează prin exerciţii logopedice şi, în funcţie de motivaţia, abilitatea sau motivaţia personală, prin comunicarea traheoesofagiană protetică – butonul fonator. Concluzii. Actul chirurgical oncologic asupra laringelui permite condiţii de recuperare funcţională şi de reinserţie socioprofesională, chiar şi în cadrul laringectomiei totale.

Introduction

Oncologic surgery of the larynx allows for tumor excisions while preserving laryngeal functions or sacrificing the entire vocal organ, based on the staging of laryngeal cancer(1,2).

For total laryngectomies, we observed a return to normal swallowing in all operated cases. However, the resumption of swallowing occurred differently, depending on the surgical healing modalities of the patients. Surgical healing was initially obtained following the surgical closure of the pharyngostoma. Regarding phonatory function, it was completely compromised, leaving patients aphonic. As a result, many patients initially declined the surgery(2,3).

Over time, experiments have been conducted to create folds of mucosa on the anterior wall of the hypopharynx to aid in muscle contraction and facilitate the creation of an air reservoir for phonation(5).

Patients who had undergone laryngectomies, without a larynx, were able to spontaneously regain or acquire a voice compatible with social or even professional life through phonation exercises(3,4).

Meeting a laryngectomized patient who had been reeducated vocally played a significant role in convincing initially reluctant patients to undergo the surgery(5,6).

Materials and method

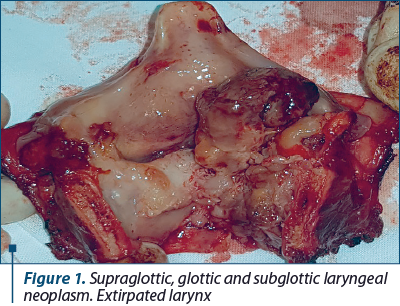

In this study, we aimed to present the functional recovery possibilities for various types of laryngectomies performed on 188 patients. Among these, 148 underwent total laryngectomies and 40 patients underwent partial laryngectomies.

Our goals were to ensure breathing, phonatory recovery and swallowing recovery.

Results

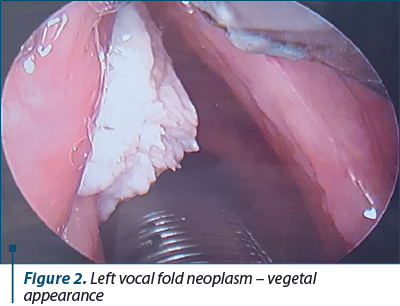

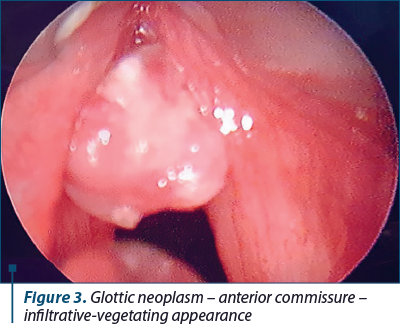

From the analysis of the patients operated on and grouped into these categories, we derived the following results concerning the preservation, alteration or disappearance of vital and social laryngeal functions: voice, swallowing and breathing.

Vocal recovery was achieved in several ways. Initially, patients learned reflexively to create a makeshift vocal glottis at the level of the lips, producing labial words with the help of buccal airflow vibration. This manner of phonation had poor quality, but in some cases, it was intelligible, even though the vibratory element of the voice was highly reduced. Later, through education, patients managed to form a pharyngo-lingual glottis. For this, patients learned to reflexively store air in the esophagus, thereby acquiring an esophageal voice.

During total laryngectomies, the surgeon must preserve the cricopharyngeal muscle, which plays a crucial role in esophageal speech.

The use of swallowed air was achieved through intermittent eructation that occurred whenever the patient pronounced words. Thus, speech through erigmophonation was accomplished by repeated acts of swallowing and eructation, maneuvers that were acquired reflexively through numerous exercises, either under the supervision and advice of physicians and clinical staff, or under the guidance of a phoniatrist.

In a small number of patients (20), a voice button could be installed, significantly aiding in the speech process two months post-surgery. Twelve patients did not require a voice button replacement, as they had regained their voices and no longer needed it. Only eight patients had their voice buttons reinstalled. Patients who were unsatisfied with their phonatory recovery purchased laryngeal phones.

Reeducation in phonation varies depending on the author, but we advocate for a timeframe of approximately two months postoperatively(5). Phonation remained slightly altered, and patients remained dysphonic for the rest of their lives.

Regarding the recovery of patients who underwent conservative interventions (partial and reconstructive laryngectomies), there are several possibilities for functional recovery. In the case of horizontal partial laryngectomies (supraglottic or epiglottic), complete vocal function was preserved and remained unaltered for all patients, with their voices retaining good quality timbre.

Partial vertical laryngectomies of the frontolateral and anterior frontal types have negatively affected all laryngeal functions except swallowing.

In horizontal partial laryngectomies (supraglottic or epiglottic), it is worth mentioning the complete preservation of the vocal function which has remained entirely unaffected for all patients. Their voice has maintained its characteristic timbre and good quality.

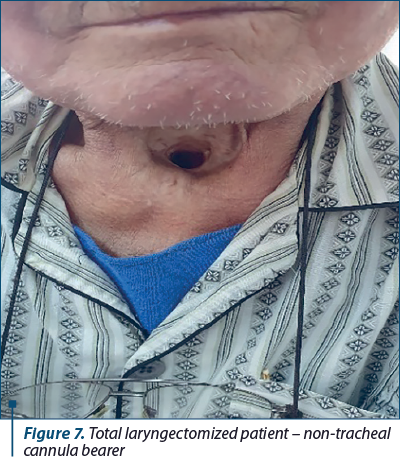

Regarding natural respiration, this constituted the most significant and consistent functional deficit in total laryngectomies. All laryngectomized patients remained tracheostoma bearers through which they secured their breathing, with or without a cannula, as needed, both during the day and at night. During the night, wearing the cannula was recommended as the tracheal opening could collapse during sleep. Depending on the healing process of the tracheostoma, the cannula could be removed during the day, with the awake state allowing the maintenance of an elevated head position and thus keeping the tracheal opening open.

Patients with a tracheal cannula were instructed to maintain proper hygiene by cleaning the cannula and changing the humidification filter daily, multiple times if necessary, and protecting the tracheal stoma from impurities and cold. If the tracheal rings calcified after surgery or if the cricoid cartilage could be preserved, the tracheal or respiratory opening could be kept permanently open, eliminating the need for cannula usage, which was a significant advantage in patient’s care.

Breathing was affected in the first 5-7 days after the surgery, especially in supraglottic resections and, to a lesser extent, in epiglottectomies, due to postoperative swelling of the residual laryngeal crown. Afterward, the tracheal cannula was removed, and the patients began breathing naturally. We had to maintain the feeding tube and tracheal cannula for a variable period of 2-4 weeks, after which all patients could be decannulated and could eat normally without the feeding tube.

Surgical procedures performed through laryngofissure (cordectomy, anterior frontal, frontolateral) benefited from temporary tracheostomy with the placement of Mickulicz endolaryngeal dressings to prevent bleeding or cervicofacial subcutaneous emphysema. Both the endolaryngeal dressing and the tracheal cannula were kept in place for 48 hours postoperatively, after which patients were able to breathe naturally. Their breathing was not affected, and they could breathe comfortably without shortness of breath, in all positions and during exertion.

Regarding swallowing, it was slightly impaired in the first days after frontolateral laryngectomies. Total laryngectomies were performed with the preservation of the cricoid or hyoid, depending on tumor’s location and extent. Postoperatively, patients were fitted with a nasoesophageal feeding tube and were fed with high-protein soups, milk, eggs and tea. Simultaneously, amino acid infusions and anti-secretory treatment were administered.

Swallowing exercises were performed under medical supervision, involving the simultaneous closure of the glottis and the elevation of the remaining larynx. Swallowing without coughing was normal, and patients were able to breathe naturally.

Proper pharyngeal space clearance for the passage of food bolus into the esophagus was ensured without coughing to prevent the entry of food into the larynx and trachea.

Regarding reconstructive laryngectomies, excellent results were reported in terms of breathing and swallowing after bicordocomissural laryngectomies, with only slight to moderate vocal alterations following this type of intervention.

Discussion

Laryngectomy removes the larynx, and the lungs and trachea no longer send air columns to the pharynx. The pharyngeal resonators remain unchanged. Exhaled air from the lungs is replaced by air from the esophagus and stomach, while the vocal cords are substituted with the mucosa of the posterior pharyngeal wall and the mucosa at the upper esophageal sphincter level(7,8).

Initially, patients develop buccal voice, followed by esophageal voice. To acquire esophageal voice, certain objectives must be met: creating and developing an esophageal air reservoir, which is achieved by swallowing air, and then learning to expel the air, a technique obtained through repeated exercises(9-11).

The first method, after the cervical region heals, including the pharyngostoma, involves teaching patients to drink carbonated mineral water and, when the eructation reflex occurs, attempting to phonate. After mastering the technique through multiple exercises, patients are asked to take a breath of air and try to articulate sounds. Sound articulation is essentially speech that must be correlated with erigmophonation(12,14).

To achieve erigmophonation, the ENT surgeon plays a crucial role in preserving anatomical elements to create an air reservoir and subsequently form a new glottis. This involves preserving the cricopharyngeal muscle, conserving the hypoglossal nerve, and preventing pharyngeal infection and fistula formation(13,15).

To avoid cervical infection and pharyngeal fistula formation, Sinerdol powder was applied to all muscle layers during the surgical procedure, with the surgical elimination of spaces between the pharyngeal mucosa wall and the constrictor muscles, sternohyoid muscles, and cervical skin. A nasoesophageal feeding tube was used to feed patients for 10-12 days postoperatively, after which it was removed, and patients resumed natural feeding. The reeducation process should begin as soon as possible, with consideration given to the patient’s dental condition, which should be corrected if deficient.

Psychological preparation plays a significant role in reeducating patients. It involves convincing patients to undergo surgery and postoperatively ensuring that they trust they can regain their ability to speak. A strong doctor-patient bond is established, and patients become eager to start their phonation reeducation process(12,16).

Some patients spontaneously learned to speak, and during medical checkups, it was a pleasant surprise to find that they had acquired esophageal voices. The lip-reading technique used by patients immediately after healing is intelligible and should be encouraged by their families. Through erigmophonation, patients can speak and work with both hands free(17).

Only a small number of patients used a voice button. Laryngeal phones were purchased by patients who were dissatisfied with their acquired speech(18).

All patients who underwent laryngeal surgical procedures were regularly followed-up: monthly in the first year, every two months in the second year, every three months in the third year, and then every six months after five years.

The reacquisition of erigmophonation was a satisfying moment in the process of understanding the importance of vocal reeducation for verbal communication(17,19).

Total laryngectomy patients are entitled to four free tracheal tubes annually, along with humidification filters.

We believe that, as a rule, the retirement granted to total laryngectomized patients under current regulations should not be enforced, especially for young, capable individuals, as tracheal tube use does not always pose a social or professional hindrance. Everything depends on the psychology and mindset of laryngectomized patients, as well as on their living and professional conditions.

Conclusions

1. We believe that oncologic surgical intervention on the larynx allows for functional recovery and socio-professional reintegration in the majority of cases, even in the context of total laryngectomy.

2. Despite its disabling nature, total laryngectomy enables the restoration of swallowing and phonation under convenient conditions for social life, and in some cases, even for the professional life.

3. We have patients who underwent total laryngectomy and continue working in their previous sectors of employment.

Acknowledgement. This work was supported by the grant POCU/993/6/13/153178, “Perfomanţă în cercetare” (“Research performance”), co-financed by the European Social Fund within the Sectorial Operational Program Human Capital 2014-2020.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

- Kumar B, Cordell KG, D’Silva N, et al. Expression of p53 and bel-xL as predictive markers for larynx preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 2008;134(4):363-369.

- Ogawa T, Shiga K, Tateda M, et al. Protein expression of p53 and Bcl-2 has a strong correlation with radiation resistance of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma but does not predict the radiation failure before treatment. Oncology Reports. 2003;10(5):1461-6.

- Bai Y, Hong S, Peng Z. [Expression and significance of proliferation marker and apoptosis-related genes in benign and malignant epithelial lesions of the larynx.] Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi. 2003;17(2):92-96 [Chinese].

- Obreja S, Ioniţă E, Mitroi MR, Ioniţă I. Îndreptar Terapeutic ORL. Ed. Sitech, Craiova, 2010.

- Anghelide R, Sbenghe-Ţeţu L. Aspecte de patologie oto-rino-laringologică. Ed. Medicală, Bucureşti, 1986

- Sarafoleanu C, Popescu I, Ciuce C. Tratat de chirurgie – Otorinolaringologie şi chirurgie cervico-facială, Vol I. Ed. Academiei Române, Bucureşti, 2012.

- Bogdan CI. Foniatrie Clinică. Ed. Viaţa Medicală Românească, Bucureşti, 2001.

- Brook I. Ghidul pacientului laringectomizat. Ed. Printech, Bucureşti, 2019.

- Bacalbaşa A. Cancerul laringian. Ed. Didactică şi Pedagogică, Bucureşti, 2004.

- Iman O, Sherman E, Singh B, et al. Alteration of p53 pathway in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: impact on treatment outcome in patients treated with larynx preservation intent. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(13):2980-2987.

- Bolshakov S, Walker CM, Strom SS, et al. P53 mutations in human aggressive and nonagressive basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9(1):228-234.

- Sarafoleanu D, Postelnicu V, Iosif C, et al. The role of p53, PCNA and Ki-67 as outcome predictors in the treatment of laryngeal cancer. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2009;2(2):219-226.

- Postelnicu V. Factori de predicţie şi valoarea practică a acestora în evoluţia clinico-terapeutică a cancerului de laringe. PhD Thesis, Bucharest, 2008.

- Tsang WYW, Chan JKC. Lymphoepitelial carcinoma. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (Eds.). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press, 2005; p. 132.

- Eveson JW. Mallignant salivary gland-type tumors. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (Eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press, 2005; p. 134.

- Woodson GE. Laryngeal and pharyngeal function. In: Cummings CW, Flint PW, Harker LA, et al (Eds). Cummings Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, 4th Ed, Mosby, 2005; 85:1963-74.

- Müller KM, Krohn BR. Smoking habits and their relationship to precancerous lesions of the larynx. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1980;96(2):211-217.

- Rothman K, Keller A. The effect of joint exposure to alcohol and tobacco on risk of cancer of the mouth and the pharynx. J Chron Dis. 1973;25(12):711-716.

- Remacle M. Inflammatory diseases and lasers. In: Anniko M, Sprekeslsen MB, Bonkowsky V, et al. (Eds.). Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery – European Manual of Medicine. Berlin, Springer, 2010; p. 475-481.