Un caz curios de dehiscenţă bilaterală de canal semicircular la un scenograf

A curious case of bilateral superior semicircular canal dehiscence in a scenographer

Abstract

The superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome (SSCDS) was first reported by Lloyd Minor and colleagues back in 1998. Since then, many patients have been diagnosed with this syndrome and the diagnostic and treatment protocols are constantly being developed and refined. The pathognomonic signs of this disease, like vertigo induced by loud sounds or pressure delivered into the external ear, are well known amongst audiologists and ENT doctors alike. Despite the fact that the Bárány Society has proposed diagnosis criteria for this disease and the technological progress in the domain of medical imaging is constantly providing doctors with better means to assess patients, SSCDS is still a fleeting concept, with semicircular canal dehiscence present in asymptomatic individuals or with bilateral bone defects which produce oscillopsia and mimic a bilateral vestibular loss at times.Keywords

bilateral semicircular canal dehiscenceoscillopsiabilateral Tullio phenomenonfluctuating hearing lossRezumat

Sindromul dehiscenţei de canal semicircular superior (SSCDS) a fost descris pentru prima dată de Lloyd Minor şi colegii săi în 1998. De atunci, mulţi pacienţi au fost diagnosticaţi cu acest sindrom, iar protocoalele terapeutice sunt dezvoltate şi rafinate în mod permanent. Semnele patognomonice pentru această afecţiune, cum sunt vertijul declanşat de sunete puternice sau presiunea exercitată în urechea externă, sunt bine cunoscute de medicii ORL şi de audiologii specializaţi în patologia vestibulară. În ciuda faptului că Societatea Bárány a propus criterii diagnostice pentru această boală, iar progresele tehnologice în domeniul imagisticii medicale oferă în mod constant medicilor metode tot mai bune de evaluare a pacienţilor, SSCDS este încă un concept în schimbare, cu dehiscenţe de canal semicircular prezente la persoane asimptomatice sau cu defecte osoase bilaterale care determină oscilopsie şi mimează un deficit vestibular bilateral uneori.Cuvinte Cheie

dehiscenţă bilaterală de canal semicircularoscilopsiefenomen Tulliohipoacuzie fluctuantăIntroduction

The dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal (SSCD) is a defect of the bone covering the superior part of the semicircular canal of the inner ear. This defect located in the middle cranial fossa floor allows pressure to travel in between the two spaces (labyrinth and middle cranial fossa). This results in an abnormal connection of the inner ear. Although the etiology is unclear, the occurrence may be found randomly amongst healthy individuals(1) or may cause audiological and vestibular symptoms. Symptoms like pressure-induced or sound-induced vertigo, chronic unsteadiness, hyperacusis to certain sounds and pulsatile tinnitus represent the most common findings(2), the resulting syndrome being called superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome (SSCDS).

Some studies show that the anatomical predisposing condition (bony defect or extremely thin layer of bone covering the superior part of the superior semicircular canal) is sometimes present in asymptomatic subjects(3), therefore studies have been carried out in order to explore the anatomical presentation of the bony defect. The SSCD is often bilateral (even with abnormally thin bone on one side and a full dehiscence on the other)(4), the aspect of unilateral or bilateral presentation being important for understanding not only the treatment and symptoms but for considering the indication of surgery(5).

Case presentation

We present the case of a 48-year-old male scenographer who was referred to our department with a history of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and elevated blood pressure. The patient had been previously diagnosed with benign arterial hypertension, a diagnosis for which he was currently undergoing treatment with good results. The patient was referred to our department with a history of BPPV and unsuccessful repositioning maneuvers. In addition to his history of positional dizziness, the patient had recent complaints which had developed prominently in the past 6 to 12 months. He was experiencing imbalance when walking home at night, as he would walk under street lights, imbalance which was also present during work when big objects would move around in front of him and would cause powerful light flashes. In addition to the periodical imbalance issues, the patient had noticed that the hearing, mostly in the right ear, would fluctuate during the day to the point where talking with the phone held up at the right ear would be difficult. The patient also described that there had been a couple of separate incidents where he would get occasional spells of vertigo during rounds of powerful applause.

With what seemed to be a single-sided hearing impairment, oscillopsia provoked by powerful visual stimuli and spells of vertigo that were induced by powerful sounds, we set out to investigate the patient for any possible SSCDs and other ongoing vestibular lesions.

For investigation protocols and diagnosis criteria, we tried to follow the recommendations of the Bárány Society for Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence Syndrome(2), which are separated into three types of criteria.

-

At least one symptom consistent with SCDS and attributable to “third mobile window” pathophysiology (A), including:

1) hyperacusis to bone conducted sound

2) sound-induced vertigo and/or oscillopsia time-locked to the stimulus

3) pressure-induced vertigo and/or oscillopsia time-locked to the stimulus, or

4) pulsatile tinnitus.

-

At least one physiologic test or sign indicating that a “third mobile window” is transmitting pressure (B), including:

1) eye movements in the plane of the affected superior semicircular canal when sound or pressure is applied to the affected ear

2) low-frequency negative bone conduction thresholds on pure tone audiometry, or

3) enhanced vestibular-evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) responses (low cervical VEMP thresholds or elevated ocular VEMP amplitudes).

-

High-resolution CT imaging with multiplanar reconstruction (C) in the plane of the superior semicircular canal consistent with a dehiscence.

Thus, patients who meet at least one criterion in each of the three major diagnostic categories (symptoms, physiologic tests, and imaging) are considered to have SSCDS.

Investigation and findings

The investigation methods we used targeted each type of criteria presented previously (A, B and C) and were also focused on gathering data about the patient’s vestibular and auditory impairment.

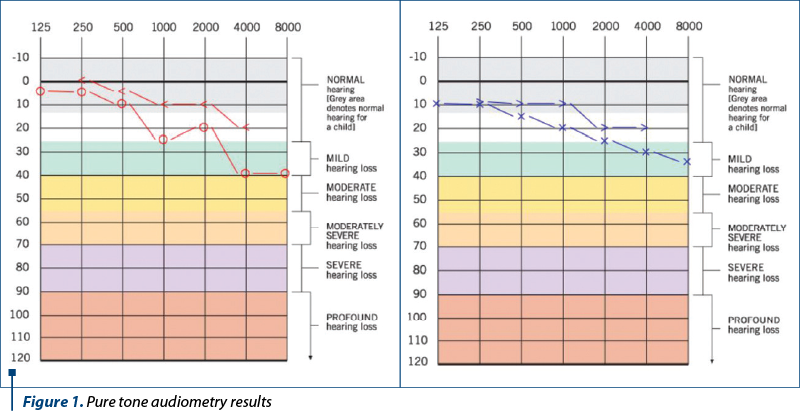

We started out with pure tone audiometry. We uncovered no hypersensitivity to bone conducted sounds, but we did diagnose a mild conductive hearing loss in the right ear and a mild sensorineural hearing loss in the left ear. The left ear displayed audiological Rinne, but within the normal thresholds.

The investigations were followed-up with tympanometry and stapedial reflex testing. The patient got dizzy during tympanometry, so the test was performed once again under infrared eye-tracking. We managed to isolate ipsilateral horizontal nystagmus during tympanometry measurements, nystagmus which was easy to reproduce after letting the patient rest for a couple of minutes and repeating the measurement. We noted the bilateral presence of the Tullio phenomenon. The patient also described spells of vertigo associated with each measurement and fluctuations in hearing levels during the actual measuring and for a short time after the end of the procedure. This finding was equally present in both ears, with nystagmus doubled by vertigo. The hearing fluctuations were described only when the right ear was tested for tympanometry. The result was a bilateral type A tympanogram, but we weren’t able to record the stapedial reflex due to high amounts of noise.

During the vestibular assessment, we found no particular abnormalities of gait and stance, thus, given the stated history of BPPV, we proceeded to investigate the patient with the help of positional tests performed under infrared cameras. We could not uncover any nystagmus characteristic to otolithic syndromes in any of the positional testing done, but a superior up-beating nystagmus was detected in both Dix-Hallpike examining positions, and it did disappear a couple of seconds after the head was brought back up in the vertical position. There was no subjective vertigo described by the patient during these tests.

Having filled out one type of diagnosis criteria (A), we indicated the patient should undergo a high-resolution CT scan for the anatomical study of the internal ear and the middle cranial fossa in order to detect bony defects.

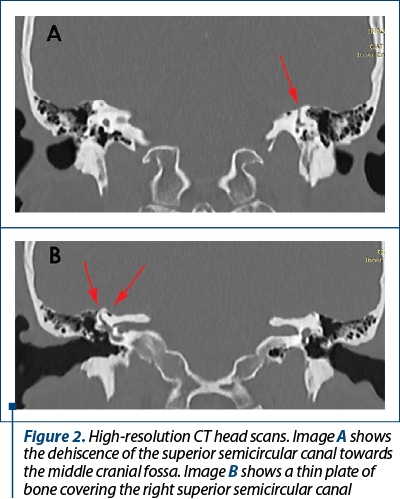

The following days, the patient underwent imaging tests. The scans uncovered a dehiscence of the superior wall of the SSC in the left internal ear and a thinned-out plate of bone covering the right SSC. The second diagnosis criterion (C) for the SSCDS was now uncovered and it was also pointing to a bilateral superior semicircular canal dehiscence.

Discussion

The patient’s symptoms were revealing of SSCDS, but the hearing impairment of the patient was present only in the right ear. The conductive hearing loss in the right ear was detected during auditory assessment and it was the only type of hearing impairment that the patient was aware of. Most likely, a unilateral hearing loss associated with typical SSCDS symptoms and positive history from the patient will reveal a unilateral symptomatic SSCD(6). However, more criteria are required for a positive diagnosis and, eventually, the high-resolution CT scan that is going to diagnose the anatomical defect or defects, if one or more are present(7). For atypical cases(8), bilateral dehiscence and dehiscence paired up with contralateral thinned out bone(9), the auditory and vestibular assessments are the ones to establish whether any of the defects are symptomatic, especially in the cases where surgery is required(10).

The bilateral presence of the Tullio phenomenon(11), although not pathognomonic of bilateral dehiscence, is a pretty strong indication in our patient that there is a third abnormal communication present in both walls of internal ears.

Positional testing may reveal if there is an ongoing BPPV present and symptomatic but, for the SSCDS(12), even in asymptomatic or least symptomatic patients, there is often a nystagmus detected in the plane of the affected canal. It is not associated with vertigo, but the differential diagnosis with anterior canal BPPV might be needed(13).

With this case, we opted for conservative treatment, as the patient’s symptoms were not that disruptive of his daily life. We opted for reducing the salt intake up to a maximum of 1 gram of salt per day, and we discussed the introduction of diuretics back into the treatment plan for high blood pressure for at least one month. In addition to this treatment plan, we opted for introducing 48 milligrams of betahistine per day. With this, we aimed the reduction of hearing fluctuations. We advised the patient to wear soft expandable silicone foam ear plugs during loud events at work in order to avoid the abrupt setting off of vertigo spells. At the 30-day check-up, the patient reported an overall improvement of symptoms – a reduction in the fluctuation of hearing levels and no episodes of induced vertigo. We decided to prolong the use of diuretics and betahistine up to three months and perform a full reevaluation at that time. This was also an issue as, at the time, the testing of cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (cVEMPs) was not available in our department, so we decided to perform the cVEMPS testing at the three-month evaluation in order to investigate for type B diagnosis criteria for SSCDS.

We considered postponing an indication for surgery in the present case as the patient was doing better despite his ongoing oscillopsia when lights were flashing in front of him. The short-term oscillopsia and unsteadiness reported by the patient could not be reproduced under experimental conditions but seem to be alike to the unsteadiness that bilateral vestibular loss patient report.

For the three-month evaluation, we plan to assess the patient’s tolerance to the treatment, recent history and symptoms and repeat the hearing tests alongside cVEMPs. We consider postponing the indication of canal plugging surgery as long as the patient is able to go throughout his daily work and habits with minimal disturbances.

Temporal bone MRI is a valuable imaging tool in the assessment of the patient with SSCDS, as some studies report(14). We did not push for an MRI investigation as the diagnosis guide we followed did not suggest such imaging tests, but would opt out for such an investigation method in pre- and/or postoperative care, if canal plugging would be performed(15).

Conclusions

Remarkable progress has been made in understanding the symptoms of a SSCD. With the improvements in CT scan’s resolution, as well as the now widespread use of infrared eye monitoring devices, more patients may be correctly diagnosed with SSCDS. For patients with persistent symptoms despite oral therapy and avoidance of the triggering factors, plugging of the canal defect is associated with the long-term symptom control(15).

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Berning AW, Arani K, Branstetter BF. Prevalence of Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence on High-Resolution CT Imaging in Patients without Vestibular or Auditory Abnormalities. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2019 Apr; 40(4):709–712.

- Ward BK, van den Berg R, Vincent van Rompaey V, Bisdorff A, Hullar TE, Welgampola MS, Carey JP. Barany Society ICVD Proposal Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence Syndrome (SCDS). 2019. Available at: http://www.jvr-web.org/images/ICVD-Barany-SCDS-V20-clean.pdf

- Carey JP, Minor LB, Nager GT. Dehiscence or thinning of bone overlying the superior semicircular canal in a temporal bone survey. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:137–47.

- Chung LK, Ung N, Spasic M, et al. Clinical outcomes of middle fossa craniotomy for superior semicircular canal dehiscence repair. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:1187–1193.

- Minor LB. Clinical manifestations of superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(10):1717–27.

- Mikulec AA, McKenna MJ, Ramsey MJ, Rosowski JJ, Herrmann BS, Rauch SD, Curtin HD, Merchant SN. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence presenting as conductive hearing loss without vertigo. Otol Neurotol. 2004 Mar;25(2):121-9.

- Branstetter BF 4th, Harrigal C, Escott EJ, et al. Superior semicircular canal dehiscence: oblique reformatted CT images for diagnosis. Radiology. 2006;238(3):938–42.

- Suryanarayanan R, Lesser TH. “Honeycomb” tegmen: multiple tegmen defects associated with superior semicircular canal dehiscence. J Laryngol Otol. 2010 May;124(5):560-3.

- Ward BK, Wenzel A, Ritzl EK, Gutierrez-Hernandez S, Della Santina CC, Minor LB, Carey JP. Near-dehiscence: clinical findings in patients with thin bone over the superior semicircular canal. Otol Neurotol. 2013 Oct;34(8):1421-8.

- Ward BK, Agrawal Y, Nguyen E, Della Santina CC, Limb CJ, Francis HW, Minor LB, Carey JP. Hearing outcomes after surgical plugging of the superior semicircular canal by a middle cranial fossa approach. Otol Neurotol. 2012 Oct;33(8):1386-91.

- Lee JJ, Ohorodnyk P, Sharma M, Pandey SK. Bilateral Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence and Tullio Phenomenon. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016 Mar;43(2):319-21.

- Brantberg K, Bergenius J, Mendel L, Witt H, Tribukait A, Ygge J. Symptoms, findings and treatment in patients with dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001 Jan;121(1):68-75.

- Anagnostou E, Kouzi I, Spengos K. Diagnosis and Treatment of Anterior-Canal Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: A Systematic Review. J Clin Neurol. 2015 Jul;11(3):262-7.

- Browaeys P, Larson TL, Wong ML, Patel U. Can MRI replace CT in evaluating semicircular canal dehiscence? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013 Jul;34(7):1421-7.

- Eberhard KE, Chari DA, Nakajima HH, Klokker M, Cayé-Thomasen P, Lee DJ. Current Trends, Controversies, and Future Directions in the Evaluation and Management of Superior Canal Dehiscence Syndrome. Front Neurol. 2021 Apr 6;12:638574.