The interrupted aortic arch is a rare congenital malformation (about 1.5% of cardiac malformations) with several anatomical variants and is often associated with other congenital cardiac anomalies. The authors present the case of a pediatric patient with aortic arch interruption and other congenital heart defects, along with the diagnostic features and indications for treatment.

Interrupted aortic arch associated with other congenital cardiac malformations

Arc aortic întrerupt asociat cu alte malformaţii cardiace congenitale

First published: 30 octombrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.71.3.2023.8972

Abstract

Rezumat

Arcul aortic întrerupt este o malformaţie congenitală rară (aproximativ 1,5% din malformaţiile cardiace) cu mai multe variante anatomice şi este adesea asociat cu alte anomalii cardiace congenitale. Autorii prezintă cazul unui pacient pediatric cu întreruperea arcului aortic şi alte malformaţii cardiace congenitale, împreună cu caracteristicile de diagnostic şi indicaţiile de tratament.

Introduction

The interrupted aortic arch is a rare congenital malformation (about 1.5% of cardiac malformations) with several anatomical variants and is often associated with other congenital cardiac anomalies. It is described as a structural interruption between the ascending and the descending aorta, associated with a patent ductus arteriosus, as this is the only way to provide distal blood flow to the interruption. In terms of the history of this condition, the anomaly has been associated with high early mortality, but the outcomes have improved in recent years, with advances in perioperative and anesthetic management and improved surgical techniques. This article aims to present the case of a pediatric patient with aortic arch interruption and other congenital heart defects, along with the diagnostic features and indications for treatment.

Clinical case

The patient V.G., aged 1 month and 2 weeks, male, with natural birth, in cranial presentation, with a gestational age of 38-39 weeks (birth weight 3300 g, Apgar score 6/7, green amniotic fluid) was transferred from his local maternity hospital to the county maternity hospital about six hours after birth with serious general condition, febrile (39 degrees Celsius), with respiratory distress (Silverman score 5), systolic murmur III-IV/VI with irradiation throughout the precordial area, with liver 3 cm below the costal margin, dysmorphic facies, motility absent on the left upper limb and decreased on the right upper limb. He was transferred to our clinic for diagnosis and the establishment of therapeutic management.

On admission, he presented with a severe general condition, with pale complexion, dyspnea mixed with tachypnoea, rhythmic heart sounds, well beating, systolic murmur grade III/VI over the whole precordial area, liver 3 cm below the rib margin, faintly perceptible femoral pulse, respiratory rate 62/minute, ventricular rate 160/min, and SpO2 89% (with oxygen on face mask). In the absence of oxygen therapy, he rapidly desaturated to 40%. Alprostadil treatment was instituted in emergency.

Blood test results showed neutrophilia with normal white blood cell count, inflammatory syndrome initially present (C-reactive protein = 63 mg/dl, subsequently decreased to 21 mg/dl), but with procalcitonin below 0.10 ng/ml and mild anemia (hemoglobin 10.2 g/dl), subsequently corrected.

Cultures of nasal, pharyngeal, tegument, otic secretion and rectal swab cultures were negative.

Chest radiograph visualized foci of intercleidohilar and right hiliobasal non-retractile pulmonary condensation with air bronchogram present; much thickened and accentuated intercleidohilar, hilar, perihilar and bilateral hiliobasal lung pattern with trabeculonodular appearance; cord with enlarged transverse diameter on account of the left lower arch; mediastinum without changes; absence of radiologically detectable pleuropericardial effusion; intestinal loops relieved of gas, without signs of free perforation or obstruction.

Echocardiography revealed the following changes: situs solitus, levocardia, patent foramen ovale, wide ventricular septal defect with left-right shunt, hypoplasia of the aortic annulus and ascending aorta, fibrous aortic valve with observation of bicuspidity, correct biventricular function. From the hardly approachable suprasternal section, a patent ductus arteriosus with wide ductus arteriosus persistence, dilated pulmonary artery and pulmonary annulus ectasia was visualized; the cavities were clear and the pericardium was free of fluid. The observation of interrupted aortic arch was established for which angio-CT was further performed.

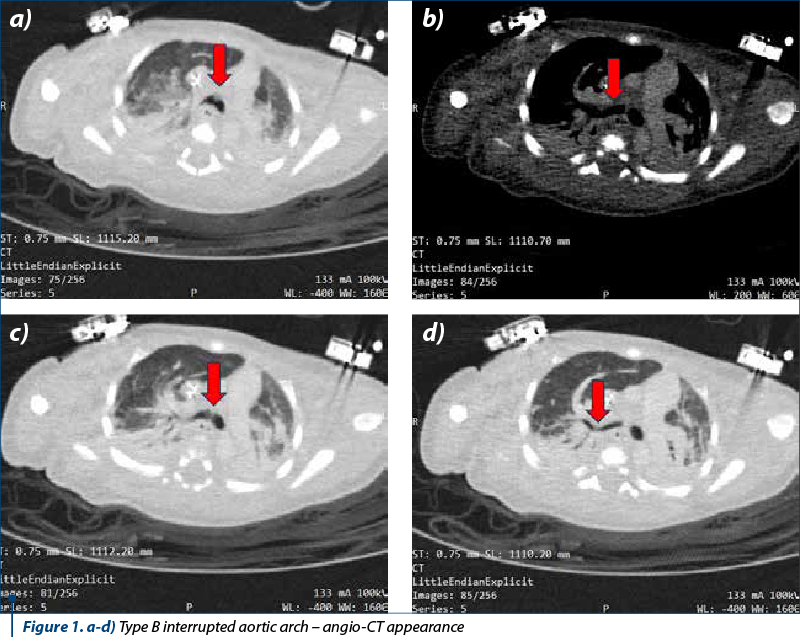

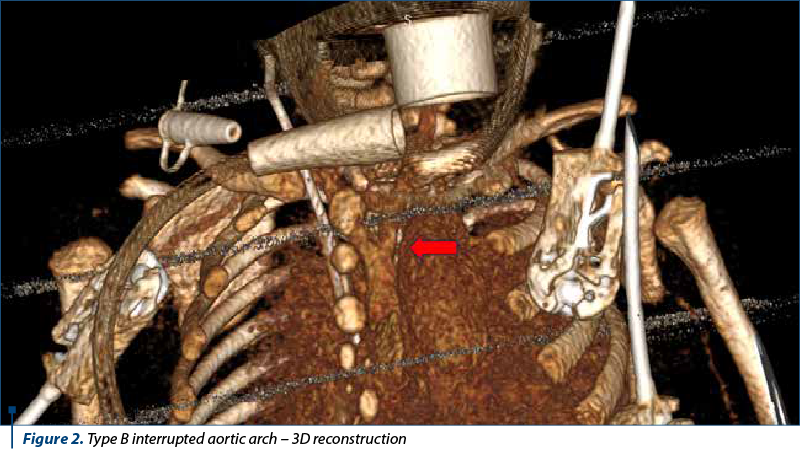

Angio-CT depicted situs solitus with 10 mm wide ventricular septal defect associated with right ventricular hypertrophy. No significant shunt was seen at the atrial level. The pulmonary trunk was 18 mm dilated and continued through the 7.7 mm ductus arteriosus with the descending thoracic aorta. The pulmonary arteries were well developed. The right pulmonary artery measured 9.3 mm and the left pulmonary artery measured 7.8 mm. Type B interrupted aortic arch was seen from the cranial end of the descending aorta, originating from the two common carotid arteries. The subclavian arteries (lusory variant for right subclavian with retroesophageal course) originate from the implantation of the ductus arteriosus in the descending thoracic aorta. The ascending aorta had a caliber of 7.5 mm, and the descending thoracic aorta had 6.7-7 mm. Aortic valve morphology could not be visualized – thickened aortic cusps and small caliber (7 mm). Coronary arteries were of normal origin, with the right dominant. Central venous catheter with apex in right atrium was visualized. There were sloping condensations in the inferior and superior lobes bilaterally against a background of hypoventilation. The conclusion was the confirmation of the diagnosis of interrupted aortic arch type B.

Thus, following diagnosis, there were established: class IV Ross heart failure, interrupted aortic arch type B, persistent patent ductus arteriosus maintained with medication (alprostadil), arteria lusoria, aortic valve dysplasia, bronchopneumonia, large perimembranous ventricular septal defect, severe pulmonary hypertension, chronic respiratory failure, dependence on mechanical ventilation.

The treatment with Tazocin® (piperacillin/tazobactam) and Targocid® (teicoplanin) was instituted for nine days, followed by Meronem® and vancomycin for seven days, along with Diflucan® (fluconazole) for 13 days.

Alprostadil dose was increased, currently receiving 250 micrograms/24 hours. The patient continued the antibiotic treatment, receiving albumin, trace elements, gastric protection and diuretics.

During hospitalization, the patient was fed by gavage, 30-40 ml Little Steps 1® every 3 hours, with good digestive tolerance, the current weight being 3500 g, with blood group 0 I, Rh positive. He was intubated and mechanically ventilated, maintaining the serious general condition, with SaO2 94%, heart rate 137/min, and blood pressure 84/44 mmHg.

Control tests revealed C-reactive protein 15.26 mg/dl, decreasing, and procalcitonin within normal limits, along with blood culture negative. Nasal and pharyngeal exudate and stool culture were collected, with negative results.

The patient is referred to a center where surgery can be performed to correct the congenital heart defects.

Discussion

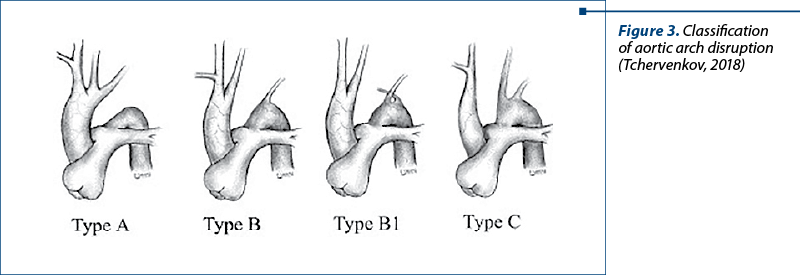

Currently, according to the Celoria and Patton classification, three types of aortic arch disruption are described. In type A, the interruption occurs beyond the left subclavian artery. In type B, the most common, the interruption occurs between the left common carotid artery and the left subclavian artery. The rarest, type C, involves interruption between the innominate and left carotid artery (Figure 1). According to the largest Congenital Heart Surgeons Society (CHSS) study of 472 patients with aortic arch interruption, reported by McCrindle et al., type A was present in 28% of patients, type B in 70%, and type C in only 1% of patients.

These three types of aortic arch interruption can be subclassified according to the origin of the subclavian artery: type 1 – normal origin of the subclavian artery; type 2 – aberrant right subclavian artery distal to the left subclavian artery; type 3 – isolated right subclavian artery(3).

Our patient has type B, the most common type.

The management of interrupted aortic arch was revolutionized in the late 1970s, with the advent of prostaglandin E1. It is recommended that full resuscitation be performed over several days, if necessary, before surgery. The preferred surgical approach is one-stage primary neonatal repair, involving direct arch anastomosis and closure of the ventricular septal defect(2). The use of selective cerebral perfusion with monitoring is becoming increasingly common. While repair of the interrupted arch is physiologically corrective, it is not a complete solution due to the high incidence of major left ventricular ejection tract obstruction at a later stage. In some cases, an extensive left ventricular ejection tract enlargement procedure may be required, while in others, a simple surgical reintervention, such as subaortic resection, may be sufficient(4). However, procedures directed against subaortic stenosis should rarely be used as part of initial surgical management in the neonatal period. Careful developmental follow-up is necessary for all patients because of the high incidence of DiGeorge syndrome, which frequently manifests as moderate developmental delay(1).

In conclusion, interrupted aortic arch is a rare cardiac malformation with serious clinical manifestations, but with a good prognosis if surgically corrected. This defect is often found in combination with other conditions and, for this reason, a careful investigation of patients is necessary. The first means of guiding the diagnosis is clinical examination, followed by echocardiography and, for confirmation, angio-CT. Once the diagnosis is established, surgical intervention is necessary to correct the defects and prevent the complications.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY licence.

Bibliografie

- Jonas RA. Management of Interrupted Aortic Arch. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;27(2):177-188.

- LaPar DJ, Baird CW. Surgical Considerations in Interrupted Aortic Arch. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;22(3):278-284.

- Ramirez Alcantara J, Mendez MD. Interrupted Aortic Arch. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; August 8, 2023.

- Tchervenkov CI, Jacobs JP, Sharma K, Ungerleider RM. Interrupted aortic arch: surgical decision making. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2005;92-102.