Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common rheumatologic disease of childhood. The complex pathophysiology and correct diagnosis of the disease form are essential for a proper therapy. JIA has several subtypes, including: oligoarthritis, polyarthritis, systemic, psoriatic arthritis, arthritis related to eczitis or spondyloarthritis, and the undifferentiated form. Symptoms associated with JIA include joint pain, stiffness and restricted movement, fatigue, fever and muscle weakness. Certain forms of the disease put children at an increased risk of suboptimal bone mineralization and osteoporosis, malnutrition, muscle weakness, mobility impairments and limitations in daily activities, including play. JIA also leads to a reduced quality of life and potentially increased mortality in adulthood. Physical activity and exercise are important components of a healthy lifestyle for all children, including children with JIA.

Updates on rehabilitation treatment in juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Actualităţi în tratamentul de recuperare în artrita juvenilă idiopatică

First published: 30 octombrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.71.3.2023.8970

Abstract

Rezumat

Artrita juvenilă idiopatică (AJI) este cea mai comună boală reumatologică a copilăriei. Fiziopatologia complexă şi diagnosticul corect al formei de boală sunt esenţiale pentru terapia corectă. AJI are mai multe subtipuri, inclusiv: oligoartrită, poliartrită, sistemică, artrită psoriazică, artrita legată de entezită sau spondiloartrită, şi forma nediferenţiată. Simptomele asociate AJI includ dureri articulare, rigiditate şi restricţii de mişcare, oboseală, febră şi slăbiciune musculară. Anumite forme de boală expun copiii unui risc crescut de mineralizare osoasă suboptimală şi osteoporoză, malnutriţie, slăbiciune musculară, deficienţe de mobilitate şi limitări în activităţile de zi cu zi, inclusiv la joacă. AJI duce, de asemenea, la o calitate redusă a vieţii şi la un potenţial de creştere a mortalităţii la vârsta adultă. Activitatea fizică şi exerciţiile fizice sunt componente importante ale unui stil de viaţă sănătos pentru toţi copiii, inclusiv pentru cei cu AJI.

Background

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common rheumatological disease of childhood, with a prevalence of 0.1-1 case/1000 children, generally with an onset between 5 and 8 years old.

The female sex is more affected, the girls:boys ratio being 2:1. Among the various subtypes, osteitis-associated arthritis affects more frequently males, while oligoarticular and polyarticular forms affect females. Europeans are particularly susceptible to developing the oligoarticular form.

The etiology is inexact, with a wide range of risk factors: susceptible genetic background (HLA I and II alleles), external or environmental factors and triggers (stress, infections, joint trauma, underlying comorbidities)(2).

Pathophysiology

A first pathophysiological element is the infiltration of the synovium with lymphocytes and macrophages, leading to a chronic inflammatory process maintained by the abnormal activity of T lymphocytes, predominant in the synovial membrane. Circulating immune complexes, C-reactive protein (CRP), rheumatoid factor (RF) and antinuclear antibodies appear, which, together with the abundance of activated Th1 cells in the synovium, produce proinflammatory cytokines (TNF alpha, IL-1, IL-6), all of them being responsible for joint destruction. The predisposing genetic background is represented by HLA class I (B27) and class II (DR4, DR5, DR8) alleles(5).

From a pathophysiological point of view, in juvenile idiopathic arthritis there are several lesional stages:

1. Exudative synovitis and minimal synovial proliferative changes.

2. Pannus formation, the initiation of articular cartilage destruction, incipient osteoporosis.

3. Advanced proliferative synovitis with extensive pannus formation, severe cartilage destruction, marked osteoporosis.

4. Fibrous ankylosis and less active inflammatory process.

5. Development of dense scar tissue with bone ankylosis.

The consequences of arthritis are represented by swelling, redness and local warmth, the limitation of movement with decreased mobility, and even stunted growth and development.

The subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis are(3):

a) systemic;

b) pauciarticular – less than five joints affected;

c) rheumatoid factor-negative polyarticular disease – more than four joints affected;

d) rheumatoid factor-positive polyarticular disease – more than four joints affected;

e) juvenile ankylosing spondylitis;

f) juvenile psoriatic arthritis;

g) arthropathies associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

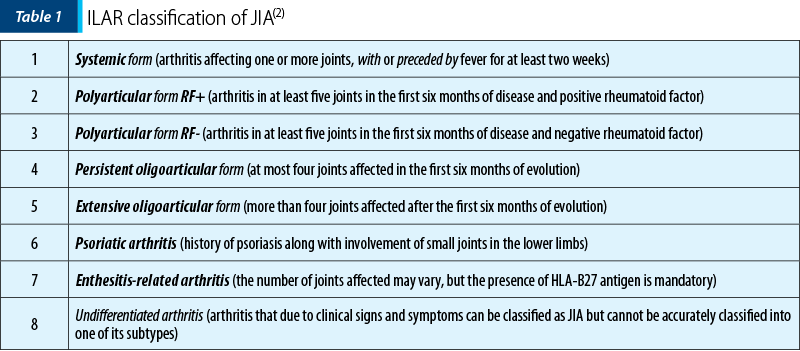

The International League Against Rheumatism (ILAR) classification divides the subtypes of juvenile idiopathic arthritis into the following forms, described in Table 1(2).

The symptomatology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis is diverse, with joint and extraarticular changes.

Joint manifestations are represented by edema of the affected joint, damage to small or large joints, locoregional pain and swelling, morning dread that improves during the day, and muscle weakness.

Extraarticular manifestations include fever, salmon-coloured rash, uveitis (photophobia, ocular congestion, headache, visual disturbances), rheumatoid nodules, pericarditis, hepatosplenomegaly, serositis, lymphadenopathy, dactylitis, as well as dermatological manifestations (psoriasis).

Physical examination may reveal(1):

- unilateral knee edema (oligoarticular form);

- the polyarticular form includes the knees, ankles and fist joints;

- subcutaneous nodules;

- deformation in the buttonhole of the fingers;

- damage to the axial joints (atlanto-axial in particular);

- decreased range of motion in the affected joints;

- nail changes and skin damage (psoriatic form);

- inflammation and tenderness at the tendon insertion (a form of arthritis with enthesitis);

- myocarditis, pericarditis, synovitis, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly (systemic form);

- torticollis with malposition of the head (cervical spine involvement);

- micrognathia (temporomandibular joint damage);

- hearing loss (middle ear interest);

- hoarse voice (interest of the cricoarytenoid cartilage);

- uveitis;

- skin rash;

- asymmetrical length of the lower limbs.

- Systemic JIA is arthritis associated with or preceded by fever, lasting about two weeks.

- Other signs that can be highlighted are:

- erythematous rash

- generalized lymphadenopathy

- hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly

- serozite.

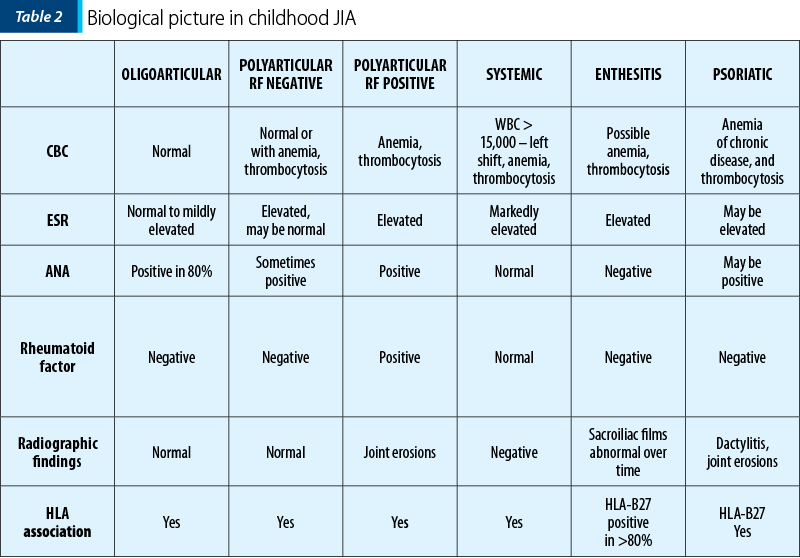

- The biological picture in AJI in children is presented in Table 2.

Laboratory and imaging tests can be performed.

- There is no specific test to specify the diagnosis of the disease.

- The tests may reveal anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, elevated liver enzymes, hypoalbuminemia, elevated acute phase reactants especially in the pus (VSH, CRP, fibrinogen), RF, ANA, CCP, genetic tests (HLA class I, II).

- If VSH is low – possible MAS (macrophage activation syndrome).

- Osteoarticular radiography may suggest joint space densities, osteoporosis, microcystic areas of epiphyseal bone structures, bone erosions, fibrous/bony ankyloses, joint deformities, or areas of bone lysis. The SENS (simple erosion narrowing score) is used to track joint destruction.

- MRI detects early joint destruction and visualises the temporomandibular joint.

- CT or DEXA can be used to characterize bone structure.

- Ultrasonography has the advantage that it is cheap, noninvasive, tolerated by the patient, and it can diagnose synovitis.

- Ophthalmic examination with biomicroscope.

- Arthrocentesis.

- Synovial biopsy.

- The diagnostic staging consists of a history of at least six weeks of arthritis with an onset below 16 years old in patients with a thorough history, appropriate objective clinical examination, complementary paraclinical investigations and a suggestive family history.

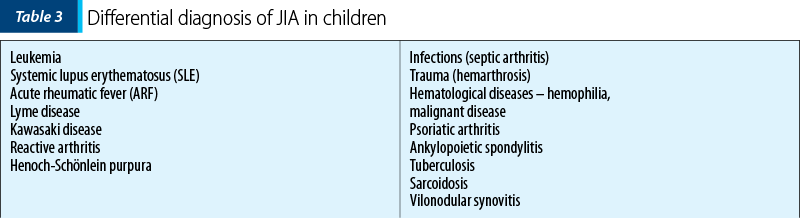

The differential diagnosis is made with the pathologies described in Table 3.

Evolution and prognosis

Systemic JIA is a dramatic disease in its systemic involvement, with a tendency to recur, but the functional prognosis is good with appropriate treatment, and the systemic signs disappear within months. Severe prognostic factors are(10):

- Onset age below 5-7 years old.

- Polyarthritis.

- Persistence of systemic signs.

- Corticosteroid therapy required even after six months of evolution.

Polyarticular JIA onset is at a young age, with an evolution, on average, of 2-3 years, complete remissions or exacerbations/remissions, rarely with severe disability, ocular sequelae to blindness. The severe prognostic factors are:

- More than one affected joint.

- Upper limb impairment.

- High VSH at onset predicts progression to polyarticular form.

- Drug treatment options are various and, depending on the degree of damage, there can be used:

- NSAIDs (naproxen, diclofenac, ibuprofen).

- Corticosteroids (oral or intraarticular – triamcinolone hexacetonide).

- DMARDs – methotrexate (oral or subcutaneous injections), sulfasalazine (peripheral onset forms), antimalarials, cyclosporine, azathioprine, gold salts, i.v. cyclophosphamide.

- Biological therapy (anti-TNF alpha) – etancercept, infliximab, adalimumab.

- Selective modulators of the costimulation pathway – abatacept, IL-1 antagonist (anakinra), IL-6 inhibitor (tocilizumab).

- Complementary and alternative treatments – homeopathy, traditional Chinese medicine, hypnosis, biofeedback, aromatherapy, therapeutic massage, chiropractic, herbal supplements, relaxation techniques.

- Psychological treatment.

- Occupational therapy.

The objectives of the rehabilitation treatment are:

1) Patient and family education.

2) Pain relief.

3) Preservation of joint function.

4) Appropriate treatment of extraarticular manifestations.

5) Psychological and social support of chronic disease.

6) Prevention of secondary disabilities, bone destruction, joint deformities, physical disability.

7) Maintain normal growth.

8) Improving quality of life.

9) Increased muscle strength and endurance(8).

The team is complex, consisting of a pediatric rheumatologist, ophthalmologist, nutritionist, orthopedist, rehabilitation doctor, physiotherapist, occupational therapist and social worker. Rehabilitation therapy in JIA involves several methods: individual physiotherapy, electrotherapy, physiotherapy, and surgical treatment in advanced stages.

A. Individual physiotherapy

The objectives of the remedial treatment are:

- Combating pain and inflammation to ensure the patients’ quality of life.

- Prevention of muscle contractures or atrophy.

- Combating the installation of joint twists, vicious positions.

- Increase and maintain joint mobility and elasticity of affected structures.

- Maintaining and being aware of the correct alignment of the spine and peripheral segments.

- Toning of abdominal, paravertebral and gluteal muscles.

- Ensuring neuropsychic tone.

- Maintain/increase functional capacity, joint function and mobility.

- Motor coordination exercises, dexterity.

Absolute bed rest is rarely indicated, being reserved only for patients with severe progressive disease and altered general condition. Continued application of the programmes is mandatory, preventing the onset of ankylosis.

The principles of kinetoprophylaxis are:

- Avoiding joint overload.

- Cycling at the expense of excessive walking.

- Correcting the posture of the cervical-dorsolumbar spine at all times.

- Long-term avoidance of sitting.

- Exercises will be performed at a moderate pace, being aware of the modality of gestural economy (hand/fist/elbow/knee/hip).

- Use of heat to combat morning dread and decrease muscle fiber spasticity.

- Postural hygiene measures consist of:

- Keeping the head up, looking forward and backward with the shoulders.

- Adopt at least three times a day an orthostatic position with your back against the wall, so that it is touched with your heels, shoulders and neck.

- During night/day rest it is advisable to use a hard, straight and smooth bed, a small pillow under the head, and a bolster under the lumbar region.

- The lower limbs should be stretched out, without support below the knees to combat the tendency to flex the thighs and knees.

- Shoulders in 45-degree abduction (possibly with a pillow between chest and arm).

- Elbows bent at 90 degrees and prone 25 degrees.

- Fists in slight extension, without radial or ulnar deviation.

- Bending fingers.

- Full extension, no rotation, no flexion/valgus/varus of the thighs.

- Legs at right angles to the calf.

Rehabilitation physiotherapy involves exercises performed in different positions, which must be explained to the patient and performed correctly under medical supervision and then mastered by the patient.

a) In clinostatism – postural exercises introduced by Forestier:

1. Lying supine, without a pillow under the head, with a small pillow under the chest, hands clasped under the occiput and elbows tending to touch the plane of the bed during deep inspiration.

2. In the prone position, with a cushion under the abdomen, lower limbs extended and hands on the head, inhale and exhale.

b) Sitting:

- Hard-backed chairs with high, straight, hard backs are preferred.

- Knees should be at hip height.

- The soles must rest with their full surface on the floor.

- Keeping the buttocks a few centimetres from the backrest and supporting the back against it relieves the muscles and helps the lumbar spine to relax discreetly.

- Twisting the body and crossing the legs are to be avoided!

c) Active physiotherapy

Given the non-pain rule, pain medication and/or moderate thermotherapy may be used to facilitate kinesitherapy.

- Isometric (static) exercises: the subject is asked to contract his paravertebral and girdle muscles without moving any segment in space.

- First, a program of free, relaxing physiotherapy (consisting of repeated changes of posture in bed or chair) is implemented, followed by stretching (aimed at reaching the extreme limit of movement in several directions, with emphasis on extension).

- Free spinal and breathing exercises, with the obligation to continue the programme at home daily.

- The therapeutic program is based on strengthening muscle strength (isometric exercises) and stretching exercises. Splints and orthoses may be used to increase the range of motion (ROM) and prevent muscle contractures, along with correct joint alignment(4).

d) Staged physiotherapy

In acute or subacute stage:

- joint rest – in functional positions;

- orthosis – resting;

- cryotherapy – cold applications, 20 minutes, 1-2 times a day;

- physiotherapy, analgesic postural therapy;

- static exercises, rhythmic stabilizations;

- passive or assisted mobilizations – to the limit of pain and to stimulate locoregional proprioceptors (in muscles, tendons);

- gestural education – induction of muscle contraction in joints that should be immobile, with the movement of other free segments;

- ergotherapy – functional games.

During the remission period, there can be achieved:

- functional orthoses, correcting joint deformities;

- massage – relaxing;

- analgesic electrotherapy – low and medium frequency (TENS, CDD, CIMF, galvanic current, ionization), high frequency – deep oscillation;

- hydrotherapy,

- physiotherapy;

- maintaining/increasing joint mobility – mobilization, light traction;

- muscle toning – especially the extensors;

- re-education of coordination, balance, gait;

- psychotherapy;

- occupational therapy – swimming, cycling, stimulation games.

The rehabilitation of damaged joints can be achieved through various methods that mobilize the elements and restore the quality of life.

- Cervical spine – at risk of atlantoaxial subluxation (prevention by soft cervical collar).

- Temporomandibular joint is characterized by pain when chewing, limited opening of the oral cavity, stiffness, and micrognathia (change of diet, small portions, facial massage).

- Upper extremity – scapulohumeral joint impairment is evidenced by severe limitation of adduction, abduction and internal rotation. It could be usefult the nighttime use of splints in extension at 15-20 degrees with fingers in slight flexion, with strengthening of fist extensors and radial carpal muscles. Use of local heat can be useful to decrease spasm and prevent contractures.

- Lower extremity – hip and knee flexion contracture. Adoption of prone position more than 20 minutes a day, strengthening of hip extensors, abductors, external rotators, quadriceps and stretching exercises of flexors, internal rotators, adductors, hamstrings plus sports (swimming, cycling).

Mobilization of the sacroiliac joints is carried out in various ways, including the following(6):

- stretching the hamstrings at the wall;

- quadriceps stretch;

- hip adductor strain;

- hip adductor contracture;

- isometric buttock contraction;

- lower trunk rotation;

- knee flexion on thigh unilateral, later bilateral.

For the upper limb, the objectives of physiotherapy are the following:

- the preservation of the functional capacity of the affected hand, fist, elbow, or shoulder;

- the preservation of remaining functional capacity (for each stage of the disease);

- the adaptation to current activities according to the actual functional backlog;

- maintaining functional autonomy by making maximum use of remaining real capacity

Common conditions are radial deviation of the carpals and ulnar deviation of the fingers, “swan neck” or “buttonhole” fingers, spring finger, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis etc., which require appropriate treatment so that the patient retains mobility.

The recovery of the hand consists of mobilization of the fist in flexion-extension, which is done by associating a degree of ulnar tilt, toning the posterior ulna – active mobilization against resistance. Exaggerated finger stress in ulnar direction is counteracted by:

- the integrity of the collateral ligaments (local joint rest, orthosis is indicated);

- for the index finger – sufficient muscle strength of the first dorsal interosseous (toning through resistive contractions);

- for the auricular – sufficient strength of the opponent (toning)(7).

It is important to include toning of the extensor apparatus of the fingers, as well as the deep and superficial joint flexors of the fingers. For hand recovery, there are ideas for activities that could achieve joint mobilization:

- writing with correction rings;

- making paper beads;

- running a beam or other material in a radial direction;

- printing materials using the handle stamp;

- use of bimanual prehension to supplement digito-palmar prehension.

The use of orthoses is also particularly effective. The purposes of rest orthoses for joint protection are to immobilize/limit joint play, correctly position and maintain the joint axis, avoid/limit stiffness, analgesic effect, combat muscle contractures, control the tendency to deformity/deviation, ensure hand functionality, support at night or throughout the day (in acute phases). There are also corrective orthoses (rigid or dynamic) and functional replacement orthoses (static or dynamic).

The recovery of the lower limb is particularly complex, because of the importance of physiological roles. Knee support orthoses can be used to tone the quadriceps, hamstrings, passive, active, isometric mobilisations, and increase resistance to stress. For the ankle, right-angled orthoses can be used to tone the tibialis anterior, triceps surae, free dorsal and plantar flexion movements, reduce edema, contracture or vicious posture. Trophic massage should be cautious.

B. Electrotherapy consists of analgesic electrostimulation, low, medium and high frequency currents to increase muscle function. It has an analgesic, anti-inflammatory, resorptive, trophic and muscle tone maintenance role. It should not be performed in acute situations(9). For each affected joint, one session per day, for 10 days, laser therapy on painful points, hydrotherapy/balneotherapy, which is contraindicated in pustules, possibly in chronic forms with significant joint destruction.

C. Superficial heat physiotherapy consists of paraffin wraps, warm wet compresses, heated cushion (electric, chemical or gel) and hydrotherapy. Deep heat is administered by ultrasound, microwave and diathermy. The role of heat is to increase the elasticity of tissues with collagen, decrease muscle spasm, increase blood flow, reduce contracture and reduce joint stiffness. It is useful before stretching or physiotherapy.

D. The surgical treatment consists of soft tissue release, release of contractures, joint replacement (total/partial), osteotomy for severe bone deformities, epiphysiodesis in case of limb inequality (involves ablation of the growth plate in the longer limb), and synovectomy (in case of uncontrolled inflammation).

The complications of treatment are as follows:

- DMARDs – immunosuppression, risk of secondary infections and malignancies, gastrointestinal adverse effects, liver fibrosis, oral ulceration, alopecia, headache, pancytopenia.

- Corticosteroids – osteoporosis/osteopenia, avascular necrosis of femoral head, gastritis, cataracts, obesity, Cushing’s syndrome, mood swings.

- Bisphosphonates – bone metabolism impairment, toxicity.

- NSAIDs – naproxen can cause pseudoporphyria cutanea, photosensitization reactions, hepatic and gastrointestinal effects.

- Biological therapy (anti-TNF alpha, IL-1, IL-6) – skin rash, infections, demyelinating diseases, myelosuppression, optic neuritis.

- Complications of intraarticular injections – infection, pain, rash, anaphylaxis.

- Complications of surgery – infection, scarring, need for repeat surgery, pain.

The complications of the disease are multiple, including chronic nongranulomatous anterior uveitis, iridocyclitis, conjunctivitis, redness of the eyes, headaches, visual disturbances that can lead to blindness over time, growth difficulties (unequal length of limbs), motor disability, psychological disorders such as depression or anxiety, kinesiophobia, micrognathia (damage to the temporomandibular joint) with speech difficulties, MAS (macrophage activation syndrome in systemic form) – persistent fever, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, coagulopathy, bone fractures/osteopenia/osteoporosis (also due to CS treatment), muscle contracture/hypotrophy/atrophy or joint deformity, atlantoaxial instability (cervical spine involvement).

Conclusions

Chronic juvenile arthritis is not a disease but a group of diseases, and it should not result in sequelae. It is not only an adult disease, but it also affects the pediatric patient, and there are no specific tests for diagnosis. Unfortunately, it is not curable but, even though it does not hurt, it must be treated and the physical effort is not contraindicated, and it can be done within tolerance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY licence.

Bibliografie

- Dempster H, Porepa M, Young N, Feldman BM. The clinical meaning of functional outcome scores in children with juvenile arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(8):1768-1774.

- Hofer M, Southwood TR. Classification of childhood arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16(3):379-396.

- American College of Rheumatology. Juvenile arthritis. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Juvenile-Arthritis

- Klepper SE. Effects of an eight-week physical conditioning program on disease signs and symptoms in children with chronic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12(1):52-60.

- Rigante D, Bosco A, Esposito S. The Etiology of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49(2):253-61.

- Ringold S, Angeles-Han ST, Beukelman T, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Therapeutic Approaches for Non-Systemic Polyarthritis, Sacroiliitis, and Enthesitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(6):717-734.

- Stenström CH, Minor MA. Evidence for the benefit of aerobic and strengthening exercise in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(3):428-434.

- Takken T, Van Brussel M, Engelbert RH, Van Der Net J, Kuis W, Helders PJ. Exercise therapy in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a Cochrane Review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;44(3):287-297.

- Upadhyay J, Lemme J, Cay M, et al. A multidisciplinary assessment of pain in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51(4):700-711.

- Zaripova LN, Midgley A, Christmas SE, Beresford MW, Baildam EM, Oldershaw RA. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: from aetiopathogenesis to therapeutic approaches. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2021;19(1):135.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Manifestări extraarticulare în artrita juvenilă idiopatică

Artrita juvenilă idiopatică (AJI) este o boală reumatismală cronică diferită de artrita reumatoidă a adultului. În prezent reumatismul cronic a...