Introduction. The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 at the end of 2019 created difficulties regarding multiple aspects of economy, society, legal, and in the field of somatic and mental health. Medical universities had to stop the activity in hospitals and laboratories in order to orient themselves towards the virtual environment, and this accelerated transition to online education so as to minimize the impact on the educational system.

Aim. The objective of the study was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the educational system in medical students from the “Iuliu Haţieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

Methodology. In order to study the coping mechanisms used by students, we conducted a primary cross-sectional study based on retrospective, analytical and observational data analysis. A questionnaire was distributed on social media groups within the Facebook application, specific to include all years and specializations, including demographical data and questions about coping mechanisms. We used the Brief COPE questionnaire, which is derived from the 60-item COPE inventory, designed by Carver in 1989.

Results. A total of 279 students completed the questionnaire, 222 females and 57 males. During the pandemic, the female students were more likely to adopt coping strategies such as emotional support, planning and instrumental support, which belong to emotion-focused and problem-focused coping styles. Fifty percent of students agreed with the way the higher education institutions adapted to the teaching conditions in the virtual environment during the pandemic, although a similar percentage stated that there were technical problems during this time. In our university, 47% of clinical cycle students claimed that the pandemic affected their choice of residency specialization. More than half of the students believe that the grades obtained on the virtual exams were higher, but on the other hand, the same percentage of the respondents found that they learned more for the online exams than for the standard ones. Forty-eight percent of the students experienced moderate to severe depressive symptoms during this period.

Conclusions. The COVID-19 pandemic influenced mental health through direct threats to the individual’s health, but also through the indirect effects of public health policies and social distancing efforts. The educational system had to adapt to online teaching methods, and the students had to use coping methods as adaptive as possible to deal psychologically with this period.

Coping mechanisms of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic

Mecanismele de coping ale studenţilor medicinişti în contextul pandemiei de COVID-19

First published: 27 aprilie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.72.1.2023.7930

Abstract

Rezumat

Introducere. Începutul pandemiei cu SARS-CoV-2, de la sfârşitul anului 2019, a creat dificultăţi în diferite aspecte ale vieţii, economice, sociale, legale şi în ceea ce priveşte sănătatea somatică şi mintală a indivizilor. Pentru a minimiza impactul asupra sistemului educaţional, universităţile de medicină au fost nevoite să oprească activitatea în spitale şi laboratoare şi să se orienteze spre un mediu virtual, ceea ce a accelerat tranziţia spre învăţământul online.

Scop. Obiectivul acestui studiu a fost de a evalua impactul pandemiei de COVID-19 asupra sistemului educaţional la studenţii din cadrul Universităţii de Medicină şi Farmacie „Iuliu Haţieganu” din Cluj-Napoca.

Materiale şi metodă. Studenţii au completat un chestionar distribuit online pe grupurile de studenţi din anii clinici şi preclinici, care a inclus date demografice şi întrebări despre diferitele mecanisme de adaptare folosite în pandemie. A fost utilizată scala Brief COPE, derivată din inventarul COPE, cu 60 de itemi, conceput de Carver în 1989.

Rezultate. Un număr de 279 de studenţi au completat chestionarul, 222 de fete şi 57 de băieţi. În perioada pandemiei, studentele au folosit mai frecvent strategii de adaptare precum suportul emoţional, planificarea şi suportul instrumental, care aparţin stilurilor de coping focalizate pe emoţii şi pe probleme. 50% dintre studenţi au apreciat modalitatea în care universitatea a reuşit să se adapteze condiţiilor de predare din pandemie, dar, în acelaşi timp, un procentaj similar au considerat că au existat dificultăţi tehnice. În cadrul Universităţii de Medicină şi Farmacie „Iuliu Haţieganu”, 47% din studenţii din anii clinici au susţinut că pandemia le-a influenţat alegerea de la rezidenţiat. Mai mult de jumătate dintre studenţi au considerat că notele au fost mai mari când au fost evaluaţi online, dar, pe de altă parte, un procentaj similar dintre studenţi au susţinut că au învăţat mai mult pentru examenele online decât pentru cele standard. 48% dintre studenţi au avut simptome moderate sau severe de depresie în perioada pandemiei.

Concluzii. Pandemia de COVID-19 a influenţat sănătatea mintală a indivizilor prin efectele directe asupra stării de sănătate, dar şi indirect, prin politicile de sănătate publică şi eforturile de distanţare socială. Sistemul educaţional a trebuit să se adapteze la metodele online de predare, iar studenţii au fost nevoiţi să folosească metode de coping cât mai adaptative pentru a face faţă psihologic acestei perioade.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on all aspects of life, causing significant psychological distress. Individuals had to make major changes in a relatively short time to adapt to life during the pandemic. Some of these changes consisted of social isolation from family and friends, encountering financial difficulties, facing the death of loved ones, and passing through illness of close people or even themselves. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of depression increased by 20%, the rate of anxiety increased by 35% and the rate of stress increased by 53%. It is estimated that 11.84% of the community members have experienced suicidal ideation(1). Healthcare providers may be particularly vulnerable to mental health difficulties due to a higher risk of disease exposure for themselves and their family members, increased work intensity and duration, and lack of personal protective equipment.

In addition to the repercussions on a personal level, the epidemiological situation represented a challenge for the educational system. The rapid evolution of the pandemic has caused medical education to be transferred to the online environment, a novelty in the way of training of thousands of students. A prevalent concern among students was the lack of access to patients, which affected the acquisition of practical skills. It also had a huge impact on the choice of specialty and self-confidence as future doctors.

An American study, including a total of 741 medical students, found that the majority of students (74.7%) believed that the pandemic significantly affected their medical education, and 61.3% believed that they should continue with normal clinical rotations during the pandemic. Also, 83.4% of the students were willing to accept the risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 if they had to return to a clinical setting(2). A survey of 2661 medical students found that the majority of students (59.9%) wanted a postponement of their final exams due to intimidation and loss of confidence in their ability to become a competent doctor in the future(3).

Coping mechanisms

Stress is defined as a state in which homeostasis is threatened (or perceived to be threatened) by unpredictable and uncontrollable environmental conditions(4). According to the American Psychology Association (APA), coping mechanisms are any conscious or unconscious adjustment or adaptation that reduces the tension and anxiety of a stressful experience or situation(5). Two general patterns of behavioral coping have been identified in both animals and humans: active coping and passive coping. Active coping is symbolized by direct engagement with threat – fighting and aggression in territorial animals, problem facing in humans. On the other hand, passive coping is associated with withdrawal and low levels of aggression or indirect responses such as avoidance and evasion.

Reactive strategies are those that we can use after the onset of stress to relax, so that we can solve the problems generated by the stressors. These strategies can be combined to generate additional benefits. They include deep breathing exercises, reframing the problem in a creative way so that we can solve it more easily, focusing on small victories, or mental visualization exercises where we imagine ourselves successfully dealing with the stressor(6).

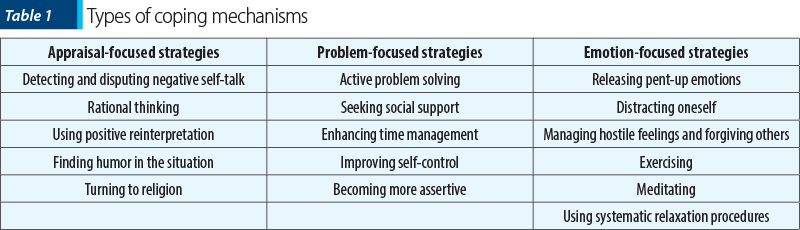

In Table 1, there are some of the most used constructive coping mechanisms(7).

Examples of maladaptive coping strategies include dissociation, denial, catastrophizing, sensitization, avoidance, procrastination and escape (including self-medication). These coping strategies interfere with the person’s ability to separate the association between the situation and the anxiety symptoms.

There are many coping scales, but the most commonly used is the COPE questionnaire(8). It is a multidimensional inventory developed to assess the different coping strategies that people use in response to stress. The questionnaire consists of a list of statements that participants review and score based on how often they use a particular coping pattern. There are two main components of the COPE inventory: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Five scales aim to measure each of these. The following are used for problem solving: active coping, planning, suppression of competing activities, withholding coping, and seeking instrumental social support. Emotion-centered coping measures are represented by seeking social emotional support, positive reinterpretation, acceptance, denial and turning to religion. Similar to the COPE inventory, the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES) was created to measure an individual’s confidence in their coping strategies when it comes to managing challenges and stressors. The Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI) was created to measure different proactive approaches to coping with stress, and contains seven subscales to achieve this: proactive coping, preventive coping, reflective coping, strategic planning, seeking instrumental support, seeking emotional support and, last but not least, avoidant coping.

Aim and design

Aim of the study

The purpose of this paper was to assess the coping mechanisms used by the students from the “Iuliu Haţieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, from any specialization and year, during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 – October 2021). The differences between study years and specializations regarding the coping strategies used to overcome this major shift in all aspects of life were also evaluated.

Design and sample

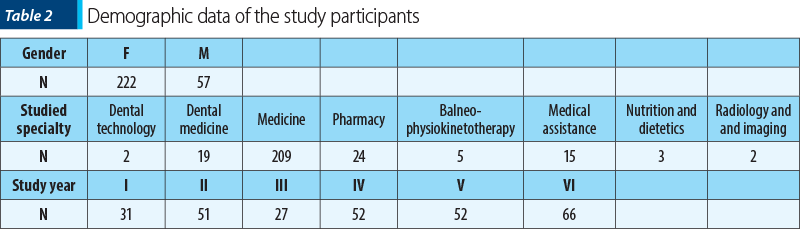

In order to study the coping mechanisms used by students, we conducted a primary cross-sectional study based on retrospective, analytical and observational data analysis. The questionnaire was distributed on social media groups within the Facebook application, specific to include all years and specializations. Thus, a sample of 279 participants was formed, of which 222 were female and 57 were male. Of these, 209 were students in general medicine (GM), 24 in pharmacy (FR), 19 in dental medicine (DM), 15 in medical assistance (MA), five in balneophysiokinetotherapy (BFK), three in nutrition and dietetics (ND), two in dental technology (DT),, and two in radiology and imaging (RI). Among the participants, 31 were in the first year of study, 51 in the second year, 27 in the third year, 52 in the fourth year, 52 in the fifth year, and 66 in the sixth year. The questionnaire had to be completed in one session, and the identity of the participants was anonymous. The participants were also asked to mention their gender and year of study, and those who submitted an incomplete questionnaire were excluded.

Study questionnaire

To evaluate the adaptation mechanisms of the students, we used the Brief COPE questionnaire. The questionnaire is derived from the 60-item COPE inventory, designed by Carver in 1989 (a multidimensional inventory to assess the various coping strategies that people use in response to stress). It consists of 28 statements and is more focused on understanding the frequency with which people use different coping strategies in response to various stressors. The participants using the inventory rated the statements from 1 to 4, with 1 representing “I didn’t do this at all”, and 4 representing “I did this a lot”. The questionnaire measures 14 different coping reactions, namely: self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, emotional support, instrumental support, behavioral non-involvement, ventilation, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, religion and self-blame(9).

Data collection and analysis

For data analysis, we used the SPSS program (IBM Corp, Armonk USA) for Windows. The alpha threshold chosen was 5%, so a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We considered the data to be continuous because of the way we calculated the scores, namely by averaging the responses. We used parametric tests of comparison of means. The difference in means between two groups was analyzed by applying T-Student and Levene’s tests of equality of variances, according to which the T-Student test was interpreted. For the difference in means between more than three groups, we used ANOVA analysis, and if it was significant, we used post hoc tests with Tukey’s correction.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 279 students participated in the current study, of which 222 were female and 57 were male. Of these, 209 were students in general medicine (GM), 24 in pharmacy (FR), 19 in dental medicine (DM), 15 in medical assistance (MA), five in balneophysiokinetotherapy (BFK), three in nutrition and dietetics (ND), two in dental technology (DT) and two in radiology and imaging (RI). Among the participants, 31 were in the first year of study, 51 in the second year, 27 in the third year, 52 in the fourth year, 52 in the fifth year and 66 in the sixth year. Table 2 summarizes all the demographic data collected.

Differences between gender, specialization and study year

Among the 14 coping reactions, the ones that had a predominant score of 4 were: humor, acceptance, active coping, ventilation and emotional support. For planning, positive reframing and self-distraction, the most frequently reported score was 3, while religion, substance use and behavioral noninvolvement ranked last, being the least used adaptation mechanism, with a predominant score of 1.

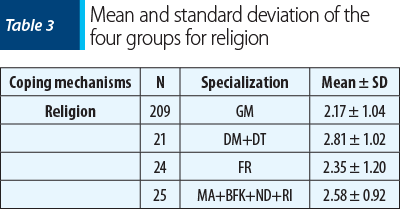

Following the distribution by specialization, we formed four groups, namely: students from general medicine (209), students from dental medicine together with those from dental technology (21), students from pharmacy (24), and students from medical assistance, balneophysiokinesiotherapy, nutrition and dietetics, and radiology and imaging (10). The groups were chosen based on similar study programs and duration of studies. We performed multiple comparisons between these four groups using one-way ANOVA analysis. The results indicate significant differences between the four groups for religion (p=0.02). Pairwise comparisons using the post hoc Tukey HSD test revealed significant differences between students from general medicine and those from dental medicine, together with those from dental technology (DM+DT) (p=0.038), with higher values in favor of those from dental medicine and dental technique, as presented in Table 3. There were no other significant differences between other groups for the rest of the coping mechanisms (p>0.05).

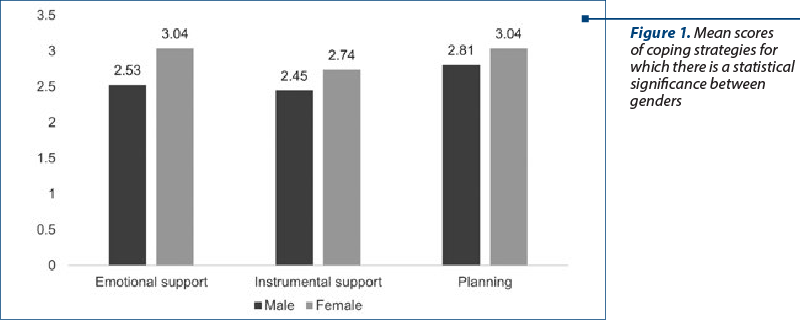

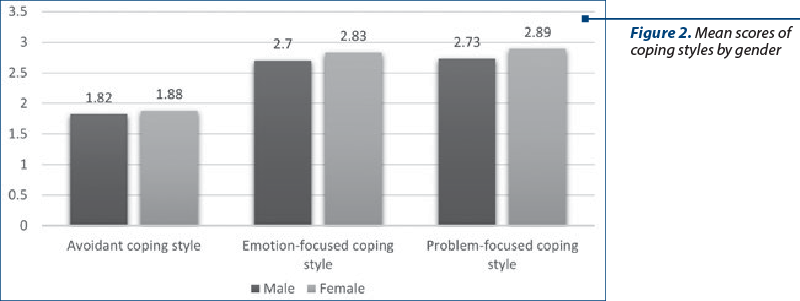

The comparison of coping strategies between genders showed significantly higher mean scores for emotional support in women (p=0.002). Also, women used significantly more instrumental support (p=0.031) and planning (p=0.033) (Figure 1).

We also grouped these coping mechanisms under three coping styles. The three coping styles used were: avoidant coping style, emotion-focused coping style, and problem-focused coping style. Within the avoidant style, we included the following mechanisms: self-distraction, denial, substance use, and behavioral noninvolvement. Within the emotion-centered framework, we included emotional support, venting, humor, acceptance, self-blame and religion. The last coping style used was the problem-focused one in which we included active coping, use of instrumental support, positive restructuring and planning. The mean for each coping style was higher in the female group, but without statistical significance. However, the results for the emotion-centered style (p=0.06) and the problem-centered style (p=0.053) were close to significance. The results are presented in Figure 2.

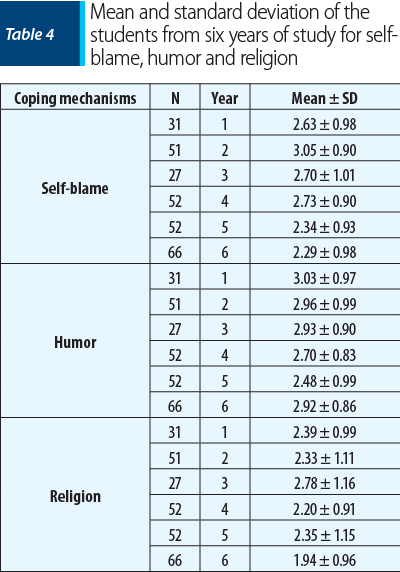

Similarly, we performed comparisons between years of study using ANOVA analysis. The results reveal a significant difference in scores between the students of different year of study for humor (p=0.04), self-blame (p<0.001) and religion (p=0.02), as illustrated in Table 4. Pairwise comparisons using the post hoc Tukey HSD test revealed significant differences for self-blame between Year 2 and Year 5 (p=0.002) and between Year 2 and Year 6 (p<0.001), with higher values in favor of second-year students. Pairwise comparisons for religion showed significant differences between Year 3 and Year 6 (p=0.007), with higher values in favor of third-year students. There were no other significant differences between other years of study for the other coping mechanisms (p>0.05). We also reported no significant differences between years of study for the three coping styles either (p>0.05).

Discussion

It is generally recognized that outbreaks of infectious diseases cause uncertainty and insecurity, as well as an alteration of rational thinking, leading to psychological stress and requiring effective coping mechanisms(10). This study showed that, during the pandemic, female students were more likely to adopt coping strategies such as emotional support, planning and instrumental support, which belong to emotion-focused and problem-focused coping styles. These results are consistent with those from the existing studies(11). Studies conducted in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that female students suffered from significantly higher levels of anxiety than their male peers, particularly in their first year, while male students experienced more depressive symptoms. All other indicators were insignificant for the gender difference. However, the mean values of all other indicators, except for three of them, were higher for women than for men, which gives an indication that women were more active than men in adopting coping strategies in response to the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results also indicate that students in medicine and dental technology used religion more as a coping mechanism compared to their peers in general medicine. The stress response after a critical event is often modified by coping processes. Although coping does not directly reduce the level of stress, it moderates its impact. Dental students used adaptive strategies such as active coping, acceptance and positive restructuring more than maladaptive strategies such as substance abuse, denial and venting(12). In our study, but without statistical significance, students in general medicine had a higher mean score for substance use compared to those from dental medicine. Religion plays a very important role in adapting to stressful situations and is a frequently used coping mechanism(13). Stronger religious belief has been shown to be associated with better mental health adjustment and functioning. Moreover, religion reduces suffering and improves coping behavior, thus helping an individual during times of crisis(14). Our study showed that third-year students used religion more to cope with the challenges of the pandemic and online education than their older sixth-year peers. This may be because the third year is a transition year, in which the transition is made from the preclinical phase to the clinical phase of the studies. Unlike their sixth-year peers who are at the end of their studies, they had to adapt to the dramatic and rapid change in the structure of learning, without access to hands-on labs and courses to facilitate their learning. Compared to the clinical phase, students in the preclinical years adopted more negative coping strategies(15). Although not statistically significant, our study demonstrated higher mean scores for the avoidant coping style within the preclinical years.

Another statistically significant result was in relation to self-blame: second-year students tended to consider themselves more blameworthy than fifth-year students. This is consistent with other findings in the literature. Second-year students’ use of self-blame may reflect their lack of self-confidence(16). Unfortunately, the use of this type of coping mechanism is associated with suicidal ideation. A study demonstrated that behavioral disengagement, venting, self-blame and denial appear to be ineffective and positive predictors of suicidal ideation among medical students(17). Humor is another coping mechanism often used. Our study was only able to show a near-significant result of the students of medicine and dental technology compared to the rest of the specializations. Although not statistically significant, it had higher means for men than women, along with substance use and acceptance. These results are consistent with those in the literature(18,19).

Implications for medical education

Even though the number of COVID-19 infections is decreasing and restrictions are being lifted, the pandemic’s negative impact on students’ mental health may persist. Therefore, it is recommended that students at universities of medicine and pharmacy be trained in the use of effective coping techniques.

Limitations

An important limitation of the present study is the use of a simplified scale, with all ratings being self-reported and dependent on the respondent’s ability to correctly understand the question and make accurate self-ratings, which was critical in the current study. Also, the sampling process included only the students of a single university. Extending the study to more universities of medicine and pharmacy in the country would bring more relevant results by using larger, more diverse groups of students. It would be useful to include more demographic variables in the future, as it would help to better describe the samples and allow more variables to be defined among which comparisons can be made. More research is needed to assess whether the current results are generalizable to other students and young adults, as the experiences of people outside the medical education system may be significantly different.

Conclusions

The respondents used different coping strategies to deal with stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. The most frequently used coping mechanisms were emotional support, venting, humor and active coping.

The current study demonstrated statistically significant gender differences for emotional support, planning and instrumental support in favor of female participants. In contrast, the mean scores were higher for male students on substance use, humor and acceptance. Religion played an important role in managing the stress caused by the pandemic. The results indicated that dental medicine and dental technician students used significantly more frequently religion as a coping mechanism compared to their general medicine peers. Comparison between years of study for religion showed that third-year students relied more on this coping strategy than their older sixth-year peers. At the same time, second-year participants blamed themselves more than those from the fifth year.

Even though coping strategies differed slightly among respondents, the vast majority of them used predominantly emotion-focused and problem-solving rather than avoidant coping strategies. This suggests that students were willing to deal with the pandemic in a positive way.

Finally, training students to increase their use of more productive and effective coping strategies may reduce the negative emotional responses related to the current COVID-19 pandemic. They constitute a group that should be monitored in terms of their mental health. Psychological interventions are essential to address mental health issues among students during current and future disasters.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:353–60.

-

Alsoufi A, Alsuyihili A, Msherghi A, Elhadi A, Atiyah H, Ashini A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: Medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242905.

-

Mittal R, Su L, Jain R. COVID-19 mental health consequences on medical students worldwide. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives. 2021;11(3):296–8.

-

Hockey R. The Psychology of Fatigue. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

-

VandenBos GR. APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association, 2007.

-

Joseph K, Irons C. Managing Stress. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

-

Picken JJ. The Coping Strategies, Adjustment and Wellbeing of Male Inmates in the Prison Environment, 2012.

-

Kato T. Frequently used coping scales: A meta-analysis. Stress and Health. 2015;31(4):315-23.

-

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4(1):92-100.

-

Mukhtar S. Psychological health during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic outbreak. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(5):512-6.

-

Rana IA, Bhatti SS, Aslam AB, Jamshed A, Ahmad J, Shah AA. COVID-19 risk perception and coping mechanisms: Does gender make a difference? Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021;55:102096.

-

Sikka N, Juneja R, Kumar V, Bala S. Effect of Dental Environment Stressors and Coping Mechanisms on Perceived Stress in Postgraduate Dental Students. International Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2021;14(5):681-688.

-

Abdulghani HM, Sattar K, Ahmad T, Akram A. Association of COVID-19 Pandemic with undergraduate Medical Students’ Perceived Stress and Coping. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:871-881.

-

Cruz JP, Colet PC, Qubeilat H, Al-Otaibi J, Coronel EI, Suminta RC. Religiosity and Health-Related Quality of Life: A Cross-Sectional Study on Filipino Christian Hemodialysis Patients. Journal of Religion and Health. 2015;55(3):895–908.

-

Ifrah Naaz S, Hussein RM, Khan HB, Hussein MM, Arain SA. Emotional responses and coping strategies of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Saudi Med J. 2022;43(1):61-66.

-

Stern M, Norman S, Komm C. Medical students’ differential use of coping strategies as a function of stressor type, year of training, and gender. Behavioral Medicine. 1993;18(4):173–80.

-

Akram B, Ahmad MA, Akram A. Coping mechanisms as predictors of suicidal ideation among the medical students of Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68(11):1608–12.

-

Sitarz R, Forma A, Karakuła K, et al. How Do Polish Students Manage Emotional Distress during the COVID-19 Lockdown? A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study.

-

J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4964.

-

Doruk A, Dugencı M, Ersöz F, Öznur T. Intolerance of Uncertainty and Coping Mechanisms in Nonclinical Young Subjects. Nöro Psikiyatri Arşivi. 2015;52(4):400-5.