Psychiatric comorbidities and social factors influencing delayed diagnosis for male cancer patients

Comorbidităţile psihiatrice şi factorii sociali care influenţează diagnosticul tardiv la pacienţii de sex masculin cu cancer

Abstract

Introduction. At present, there are very few studies in the scientific literature that analyze the impact of the association between psychiatric disorders and social factors at the time of the first medical consultation of the oncologic patient, resulting in a less favorable diagnosis.Objectives. The evaluation of psychiatric comorbidities and the social factors influencing the delayed diagnosis for male cancer patients.

Methodology. A battery of tests was administered to 87 male patients diagnosed with different types of cancer, treated in the Oncology Department of the CF2 Clinical Hospital in Bucharest. The level of self-esteem was assessed with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and the coping mechanisms were investigated with the Cognitive-Emotional Coping Questionnaire. The inclusion criteria for this study were: gender, age of 18 years or older, histopathological confirmation of cancer, and at least one type of oncologic treatment performed.

Results. The analysis of the answers to the administered questionnaires showed that 13.04% of patients had moderate and severe symptoms of depression, 54.03% presented moderate to severe anxiety disorder, and 29,89% had important levels of perceived stress. Married patients tend to go to medical consultations during the first three months (66.6%), whereas only 10.5% of them wait for longer than one year, while the divorced, unmarried or widowed patients tend to present at the doctor’s office after three months.

Conclusions. This study shows that marital status, presence of children in the family, anxiety and coping strategies are a part of the characteristics that influence the swiftness with which a cancer diagnosis can be established in male patients. Marital status and the presence of children in the family have a positive impact on the duration of time needed to get medical attention, whereas anxiety and several coping strategies determine a longer waiting period.

Keywords

anxietydepressionstressemotional withdrawalcancermaleRezumat

Introducere. În prezent, există puţine studii în literatura de specialitate care analizează impactul asocierii dintre tulburările psihiatrice şi factorii sociali în momentul primei adresări la medic a pacientului oncologic, rezultând un prognostic nefavorabil.Obiective. Evaluarea comorbidităţilor psihiatrice şi a factorilor sociali care influenţează diagnosticul tardiv la pacienţii de sex masculin cu cancer.

Metodologie. O baterie de teste a fost aplicată la un număr de 87 de pacienţi oncologici de sex masculin, diagnosticaţi cu diferite tipuri de cancer, aflaţi sub tratament în cadrul Departamentului de oncologie al Spitalului Clinic CF2 din Bucureşti. Nivelul încrederii în sine a fost evaluat cu ajutorul Scalei Rosenberg a Stimei de Sine. Mecanismele de coping au fost investigate folosind chestionarul de evaluare a copingului cognitiv-emoţional. Criteriile de includere pentru acest studiu au fost: genul, vârsta, confirmarea histopatologică a diagnosticului de cancer şi cel puţin un tip de terapie oncologică realizată.

Rezultate. Analiza răspunsurilor la chestionarele aplicate a arătat că 13,04% dintre pacienţi au prezentat simptome moderate sau severe de depresie, 54,03% au prezentat tulburare de anxietate moderată până la severă, iar 29,89% au avut niveluri importante ale stresului perceput. Pacienţii căsătoriţi au tendinţa de a merge la consult medical în primele trei luni (66,6%), iar 10,5% aşteaptă pentru mai mult de un an. Pacienţii divorţaţi, necăsătoriţi sau văduvi tind să se prezinte la cabinetul medical după trei luni.

Concluzii. Acest studiu arată că starea civilă, prezenţa copiilor în familie, anxietatea şi strategiile de coping fac parte din factorii care influenţează rapiditatea cu care se poate stabili un diagnostic de cancer la pacienţii de sex masculin. Starea civilă şi prezenţa copiilor în familie au un impact pozitiv asupra duratei de timp necesare pentru a solicita asistenţă medicală.

Cuvinte Cheie

anxietatedepresiestresretragere emoţionalăcancerbărbaţiIntroduction

The incidence and mortality of male cancer patients have higher rates than in women (512.1 versus 418.5, respectively 204 versus 143.4). The oncological sites with the highest death rates are lung, prostate and the colorectal area, which accounts for 42% of all cancers in men(1). At present, there are very few studies in the scientific literature that analyze the impact of the association between psychiatric disorders and social factors at the time of the first medical consultation of the oncologic patient, resulting in a less favorable diagnosis. One possible cause for the high mortality rate observed in male cancer patients is the late diagnosis determined by either a lack of screening and prevention programs implemented in the medical system, as well as by limited access to modern diagnostic methods, or by the late presentation to the doctor’s office of the patients, due to psychosocial factors such as poor coping mechanisms, depression, severe anxiety and social status(2-8). Psychiatric comorbidities lead to high morbidity and mortality rates in cancer patients(9-10). One possible explanation for this finding could be a lack of participation in cancer screening programs, either due to an avoidance of medical staff on the part of the patient, or due to a limited capacity to follow the medical recommendations(11). This study aimed to find associations between delayed diagnosis in male cancer patients and a variety of sociopsychological and medical characteristics, including psychiatric comorbidities.

Methodology

Study population

A battery of tests was administered to 87 male patients diagnosed with different types of cancer, treated in the Oncology Department of the CF2 Clinical Hospital in Bucharest. The battery of tests included questions regarding residence, marital status, level of education (low – primary school; medium – high school; superior – university), the number of children in the family, the time passed between the onset of the first signs and symptoms and the first medical consultation. This period was divided into four groups: the first group presented at the doctor’s office in less than one month since the appearance of the first signs and symptoms, the second group in 1-3 months, the third group in 3-12 months, and the fourth group after more than one year.

The study analyzed various psychological characteristics. The level of self-esteem was assessed with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (a 10-item questionnaire regarding positive and negative feelings about oneself)(12). The perceived social support was measured using the DUKE questionnaire (a 10-item questionnaire regarding help and empathy received from other people)(13). The level of depression, anxiety and perceived stress was assessed with the DASS 21-R questionnaire for psychiatric comorbidity (a 21-item questionnaire that evaluates the levels of depression, anxiety and stress, with seven items each)(14). The coping mechanisms were investigated with the Cognitive-Emotional Coping Questionnaire (CECQ) (a 36-item questionnaire that includes nine types of coping used in negative settings: self-blame, acceptance, rumination, positive refocusing, refocusing on planning, putting into perspective, catastrophizing, and blaming others)(15).

The inclusion criteria for this study were: gender (male patients only), age (18 years or older), histopathological confirmation of cancer, at least one type of oncologic treatment performed (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and/or targeted therapy). The exclusion criteria were: altered general functional status assessed by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), the performance status (ECOG>2), untreated brain metastases, temporo-spatial disorientation, decompensation of psychiatric comorbidities, and severe pain. The study was approved by the hospital’s Ethics Commission, and the participants signed the informed consent.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained in this study were statistically analyzed with SPSS 22.0 for Windows by using T-test, ANOVA and chi-square test. The regression analysis gave an equation in which B is the coefficient applied to the values of the variable defined as a factor, Wald is the test tide to the statistical significance of B and EXP(B) is the exponential of B, and its value represents the chance report OR. The hypothesis that the time of presentation to the doctor is influenced by different variables was tested using ordinal regression analysis. The chi-square (Pearson) tests, the degrees of freedom (df), which shows how many values are independent, the total variation according to pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke), and the regression coefficient b of the ordinal regression equation were used in this statistical analysis. The predictive power of the time presented to the doctor was determined by the level of difference between the two probability distributions, -2 Log-Likelihood intercepted and the values of statistical significance of the regression coefficient b.

Results

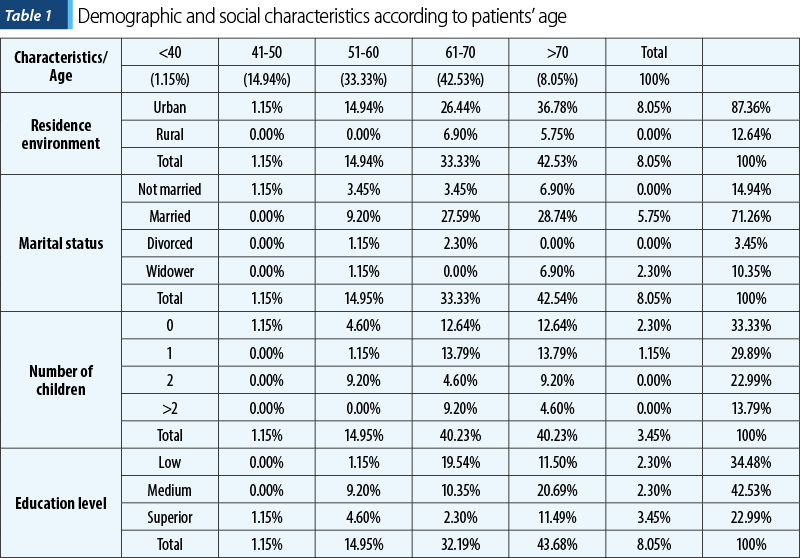

The age of the patients included in the study varied between 26 and 79 years old. The mean age was 59.94 years old, and the median age was 61 years old. The age distribution and the social characteristics were unequally distributed in the study group. The majority of the patients had a residence in the urban environment (87.36%), were married (71.26%), had children (66.67%), and did not have a high level of education (77.01%) – Table 1.

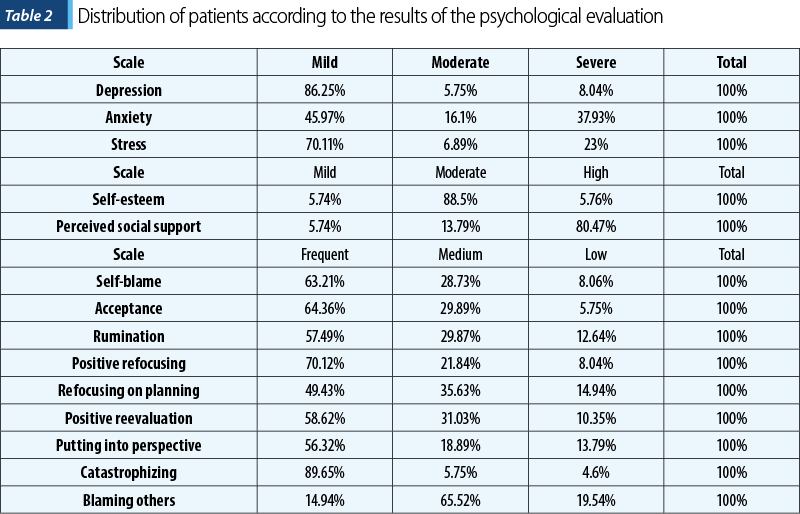

The analysis of the answers to the administered questionnaires showed that 13.04% of the patients had moderate or severe symptoms of depression, 54.03% presented moderate to severe anxiety disorder, and 29.89% had important levels of perceived stress. The majority of the patients (80.47%) reported receiving a lot of social support, and only 5.74% registered very low levels. Self-esteem had a predominantly medium level (88.5%). The analysis of the CERQ questionnaire showed frequent use of the self-blame (63.21%), acceptance (64.36%) and catastrophizing (89.65%) coping mechanisms (Table 2).

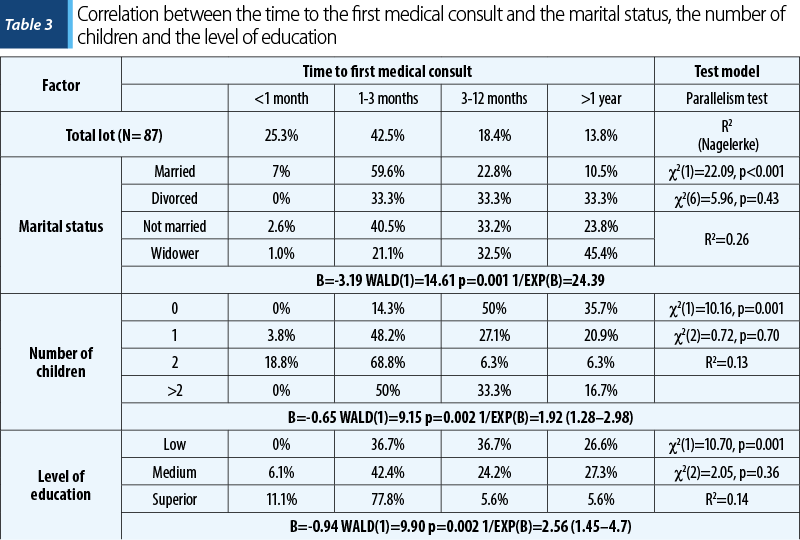

A significant number of patients declared they had their first medical consultation during the first three months (67.8%), followed by patients who presented for the first consultation in three to 12 months after the first signs and symptoms appeared (18.4%), and 13.8% declared they had their first consultation after more than one year. The statistical analysis revealed significant correlations between the time to the first diagnosis and marital status, the number of children, or the level of education (Table 3).

The married patients tend to go to medical consultations during the first three months (66.6%), whereas only 10.5% of them wait for longer than one year, while divorced, unmarried and widowed patients tend to present at the doctor’s office after three months (66.6%, 57% and 77.9%, respectively; p<0.001). Ordinal regression analysis revealed that marital status influences the moment one shows up to the doctor. The assumption regarding equal regression coefficients for different levels of anxiety has not been invalidated (chi-square=0.07, higher than 0.05). There is no statistically significant difference between the determined model, the logistic link function and the observed data, because chi-square (Pearson)=5.96, df=6, and p=0.43. The predictive strength of the show-up time based on anxiety level is higher than the value provided by the marginal frequencies, the level of difference between the two probability distributions -2 Log-Likelihood intercepted and final is, according to the concordance test chi-square=22.09, highly significant (p<0.001), the model explaining 26% of the total variation; pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke)=0.26. The best prediction was for married men, the regression coefficient b=-3.19 being highly statistically significant. Wald test was equal to 12.22 and p<0.001, with a confidence interval (CI) 95% (-4.82/-1.55). The odds ratio of married men showing up later than one year is 24 times lower than showing up earlier.

In the group of patients who had children and presented at the doctor’s office for medical consultation in less than three months, the results were as follows: 87.6% had two children, 52% had one child, and 50% had more than two children. The patients with no children tended to have their first medical consultation after more than three months (50%), while 35.7% of them waited for over one year. Regarding the number of children, the assumption of equal regression coefficients for different levels of anxiety was not invalidated, chi-square=0.7. A statistically significant difference was observed according to chi-square (Pearson)=28.04, df=8, and p=0.01. The predictive strength of the show up time based on anxiety level was higher, chi-square=10.16 and p=0.001. The model explains 13% of the total variation, pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke)=0.13. The regression coefficient b=-0.65 is statistically significantly higher than the ones corresponding to another marital status according to the Wald test=8.95, p=0.003, with 95% CI (-1.08/-0.22). The odds ratio for men with children showing up later than one year is about two times lower than earlier.

Similar statistical correlations were in the case of education level (chi-square=0.36). There is no statistically significant difference according to chi-square (Pearson)=5.87, df=5, and p=0.32. The predictive strength of the presentation time based on the anxiety level is higher than the value provided by the marginal frequencies, since chi-square=10.70, p=0.001, the model explaining 13.7% from the total variation, pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke)=0.137. The regression coefficient b=-0.94 is statistically significantly higher than the ones corresponding to another marital status, according to the Wald test=9.62, p=0.002, 95% CI (-1.53/-0.35). The odds ratio for men with a high level of education to show up to the doctor after one year is approximately 2.56 times lower than earlier.

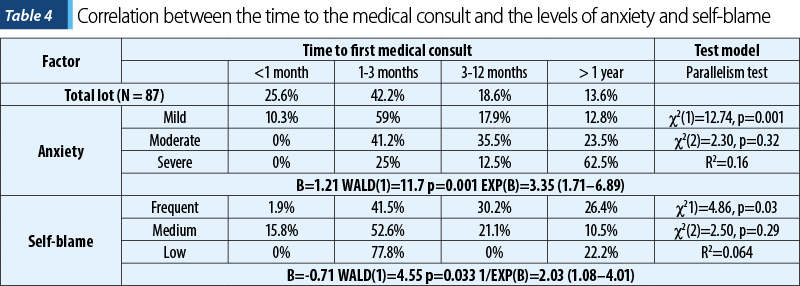

Regarding the psychological characteristics, only anxiety and self-blame coping mechanisms showed a statistically significant correlation with the time to the first medical consultation. Patients with severe anxiety tended to ask for medical help after more than one year from the first signs and symptoms (62.5%), while 69.3% of patients with milder symptoms of anxiety tended to get consultations in the first three months (p=0.001) – Table 4. The correlation between the showup time to the doctor and the level of anxiety revealed a level of significance of the chi-square test equal to 0.32. There is no statistically significant difference since the chi-square (Pearson)=2.96, df=5, and p=0.71. The predictive strength of the show up time based on the anxiety level is greater than the value provided by the marginal frequencies, chi-square=907.60, highly significant for p<0.001, the model explaining 16.1% of the total variation, according to pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke)=0.161. The regression coefficient b=1.21 is highly statistically significant according to Wald test=12.22 and p<0.001, with 95% CI (0.53/1.89). The odds ratio for men with severe anxiety to show up later than one year is 1.6 times higher than earlier.

Patients who use low self-blame coping strategies presented for the first medical consultation before three months in a higher percentage (77.8%), whereas patients who frequently used this type of coping arrived for their first medical consultation after three months (56.6%; p=0.03). The analysis of the influence of coping mechanism by self-blame regarding the showup time to the doctor revealed a chi-square test=0.29. The difference is statistically insignificant according to chi-square (Pearson)=8.25, df=5, and p=0.14. The predictive strength of the show up time based on the anxiety level is higher than the value provided by the marginal frequencies, chi-square=4.86, p=0.027, the model explaining 6.4% of the total variation, with pseudo R-square (Nagelkerke)=0.064. The coefficient b=-0.71 is statistically significant according to Wald test=4.65 and p=0.031, with 95% CI (-1.35/-0.06). The odds ratio for men with low self-blame to show up later than one year is about two times lower than earlier.

Discussion

This study analyzed the correlation between the psychosocial characteristics of male cancer patients and the late presentation for diagnosis.

Due to the prolongation of life expectancy, the incidence of cancer will increase, the advanced age being a risk factor that prevents early diagnosis. For male cancer patients, screening programs have been developed, especially for prostate and colorectal cancer, except for other locations, but one of the major problems is the late addressability to the doctor despite these programs(16). The advanced age of the patients in our study may be a barrier in the discussion of the disease and the response to the questionnaires, probably due to a poor understanding of the questions asked. On the other hand, men respond to questions about the disease in a lower percentage than women(17).

The level of education showed a significant statistical correlation with the time to the first medical examination, the patients with higher education (university, master or PhD degree) tend to get diagnosed earlier, in the first three months, while patients who have graduated primary school or high school consult a doctor more than three months after the first symptomatology or even after more than one year. The late diagnosis will have a major impact on the prognosis and the quality of life of patients.

Our results showed that the time to medical consult was also correlated with the presence of children in the family, men patients with children tending to ask for medical help more promptly, compared to patients with no children. Family support is an important component of social support, which is a strong factor correlated with the emotional state of patients diagnosed with cancer, and implicitly with the evolution of the disease. Important areas in which the family can help patients regain emotional balance are self-esteem, confidence, listening, and even the financial support. Reducing psychological stress, depression and anxiety can be done by addressing with the family the issues related to the diagnosis of cancer, fear of adverse effects of chemotherapy or radiation or postoperative physical mutilation, limited socialization, recurrence or death(18).

Self-esteem assessment, due to the particularities of each cancer patient (functional, family, socioeconomic status, stage and type of disease), must become a mandatory evaluation in order to be able to personalize the oncological therapy and to increase the patient’s adherence and compliance to the treatment. The decrease in self-esteem is accentuated by the stigma of the disease, the deterioration of the self-image through various physical changes, and by the uncertainties regarding the treatment and evolution of the disease. A balanced emotional status maintains a better quality of life(19).

Psychosocial distress occurs in about 30% of cancer patients, depression and anxiety having the highest incidence. The prevalence of depression in oncologic patients ranged between 9.1% and 31.9%, with an average of 19.2%, depending on the stage of the disease. Severe depression is associated with low adherence to treatment, negative prognosis, low quality of life, but also with the suicide risk. Although cancer patients may receive antidepressant treatment, the results are not as expected, especially in moderately severe forms of depression. An alternative to the pharmacological approach is psychotherapy, which can improve coping skills through cognitive-behavioral therapy(20).

Anxiety symptoms onset after the diagnosis of cancer is more common in women than in men. However, the location of cancer, the stage of the disease, the incidence and degree of pain, the type of oncological treatment, the family support, age, marital status, the number of children and the socioeconomic conditions must be taken into account. In this context, a gender-differentiated approach to psychological status is important, given the family or socioeconomic vulnerability and the adaptation to different variables related to cancer and its treatment(21).

The analysis of the CERQ questionnaire revealed a frequent use of self-blame, acceptance and catastrophizing coping mechanisms. Emotional withdrawal, self-blame and positive reinterpretation tend to be the most frequent symptoms in men diagnosed with cancer(22,23). The late presentation to the physician of male patients with oncological pathologies localized in the genital area is correlated with psychiatric comorbidities that associate depression, anxiety and feelings of shame, such as in the relevant case of penile cancers or rare tumors due to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections(24,25). Similar to affecting the image of femininity in breast cancer, men with genital cancer show a dramatic impairment of masculinity that increases patient’s distress. Men with HPV infection have negative emotional responses, more pronounced than uninfected men. The psycho-emotional picture is most often marked by depression, fear, fear of stigma and self-blame(26).

Regarding the time passed from the first signs and symptoms until the first medical consultation, the delay occurs due to the patient. Subsequently, until the oncological diagnosis, a second delay appears, determined by the medical system. The total time interval of the delays is 57-168 days (median: 98 days), of which 7-56 days (median: 21 days) are due to the patient, and 32-93 days (median: 55 days) are due to the medical system. The duration differs depending on the location and stage of cancer(27). If the medical system can review procedures to shorten the time to diagnosis, the early addressability of the patient to the physician depends on his age and education about cancer. The late addressability to the doctor may increase the number of emergency referrals by the family doctor, a context in which additional concerns may arise for the patient and his family(28). It is estimated that 10-25% of cancer patients have a long duration from the presentation to the physician to the oncological diagnosis. For the most common cancers in men, this time is 49-54 days for lung and colon cancer, respectively 137 days for prostate cancer(29).

The time to medical consult was correlated with the marital status and the presence of children in the family. There is no much data in the literature that supports these findings; however, there are correlations in previous studies regarding preventive behavior, marital status, and the presence of children in the family. People who live alone have a higher risk of illness, and mental health and quality of life are affected by the lack of support when they are going through the suffering caused by a disease, especially cancer(30). On the other hand, a single person, elderly or with a low educational level, may not recognize the symptoms of cancer, neglect it, or be afraid to go to a doctor(31).

Several studies have found a correlation between a lower level of education and the late cancer diagnosis(32,33). The possible causes for this correlation are a lack of medical knowledge and difficulties in accessing professional medical help. Patients with severe anxiety tend to ask for medical help over one year after the first signs and symptoms appear. The presence of psychiatric comorbidities, like depression and anxiety disorders, determines a late diagnosis for patients with somatic disease and, in the case of cancer patients, it is associated with an unfavorable prognosis and evolution of the disease(34-38).

Conclusions

This study shows that marital status, presence of children in the family, anxiety and the coping strategies are a part of the characteristics that influence the swiftness with which a cancer diagnosis can be established in male patients. Marital status and the presence of children in the family have a positive impact on the length of time needed to get medical attention, whereas anxiety and several coping strategies determine a longer waiting period. One notable find is the fact that men without children and men who are unmarried, divorced or widowed frequently associated a higher risk of developing symptoms of depression, in addition to a late diagnosis of neoplasms, due to engaging in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and alcohol abuse. In light of the fact that psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression, anxiety disorder or psychotic disorders, are frequently associated with a poor prognosis in oncology diseases, better screening programs should be developed in order to care for these patients. Early psychological assessment of male cancer patients can lead to better compliance and adherence to specific oncological treatments, to a better prognosis and to a higher quality of life.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained the approval of the Ethics Committee of No. 2 Railways Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, Romania, for this study (No. 436/14.01.2019).

Abbreviations

DASS: Depression, anxiety and stress scales.

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

CI: Confidence Interval.

SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30.

-

Al-Azri MH. Delay in Cancer Diagnosis: Causes and Possible Solutions. Oman Med J. 2016;31(5):325-326.

-

Allgar VL, Neal RD. Delays in the diagnosis of six cancers: Analysis of data from the National Survey of NHS Patients: Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(11):1959–70.

-

Al Busaidi A, Al-Balushi S. Health Education in the Sultanate of Oman. In: Health education in context: an international perspective on the development of health education. Rotterdam: Tylor N, Quinn F, Littledyke M and Coll R (eds.) Sense Publisher; 2012. 17-25 p.

-

Green T, Atkin K, Macleod U. Cancer detection in primary care: insights from general practitioners. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(S1 Suppl 1):S41–9.

-

Jones R, Latinovic R, Charlton J, Gulliford MC. Alarm symptoms in early diagnosis of cancer in primary care: cohort study using General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2007;334(7602):1040.

-

Koyi H, Hillerdal G, Brandén E. Patient’s and doctors’ delays in the diagnosis of chest tumors. Lung Cancer. 2002;35(1):53–7.

-

Jidveian Popescu M, Ciobanu A. Factors Influencing Delayed Diagnosis in Oncology. Maedica (Bucur). 2020;15(2):191–5.

-

Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49(6):599-604.

-

Cunningham R, Sarfati D, Peterson D, Stanley J, Collings S. Premature mortality in adults using New Zealand psychiatric services. N Z Med J. 2014;127(1394):31-41.

-

Lawrence D, Hancock K, Kisely S. Cancer and mental illness. In: Sartorius N, Holt R, Maj M, editors. Comorbidity of Mental and Physical Disorders. Key Issues in Mental Health Basel. Switzerland: Karger; 2015. pp. 88–98.

-

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ. Science. 1965;148:804.

-

Koenig HG, Westlund RE, George LK, Hughes DC, Blazer DG, Hybels C. Abbreviating the Duke Social Support Index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics. 1993;34(1):61-9.

-

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. DASS Manual for Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – DASS 21-R. Adaptation and standardization of DASS for Romanian population by Perte A and Albu M. Cluj-Napoca: Cognitrom. 2011; pp. 5–15.

-

Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P, Perte A. Emotional-cognitive coping questionnaire, CERQ. Adaptation and standardization of DASS for Romanian population by Perte A. Cluj-Napoca: Cognitrom. 2010; pp. 2–30.

-

Shieh Y, Eklund M, Sawaya GF, Black WC, Kramer BS, Esserman LJ. Population-based screening for cancer: hope and hype. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(9):550-65.

-

Moore DL, Tarnai J. Evaluating nonresponse error in mail surveys. In: Groves RM, Dillman DA, Eltinge JL, Little RJ, editors. Survey Nonresponse. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. pp. 197–211.

-

Usta YY. Importance of social support in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(8):3569-72.

-

Leite MAC, Nogueira DA, de Souza Terra F. Evaluation of self-esteem in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2015;23(6):1082-9.

-

Fernandez-Robles CG, Pirl WF. Depression, Anxiety, and Fatigue. In: Harrison’s manual of oncology. Second edition. Chabner BA (ed.), Lynch TJ (ed.) and Longo DL (ed.), McGraw Hill Education/Medical, New York. 2014; pp. 279-288.

-

Parás-Bravo P, Paz-Zulueta M, Boixadera-Planas E, Fradejas-Sastre V, Palacios-Ceña D, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, et al. Cancer Patients and Anxiety: A Gender Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1302.

-

Spiegel D. Cancer. In: Fink G, editor. Stress Consequences: Mental, Neuropsychological and Socioeconomic. 1st ed. San Diego: Elsevier Inc. 2010; pp. 389–93.

-

Barraclough J. Emotions around diagnosis. In: Cancer and emotion: a practical guide to psycho-oncology, Third Edition. Barraclough J, John Wiley and Sons, New York. 1999; pp. 1-4.

-

Iorga L, Marcu RD, Diaconu CC, Stănescu AMA, Pantea Stoian A, Mischianu D, et al. Penile carcinoma and HPV infection (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2019;20(1):91.

-

Ciobanu AM, Popa C, Marcu M, Ciobanu CF. Psychotic depression due to giant condyloma Buschke-Löwenstein tumors. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55(1):189-95.

-

Daley EM, Buhi ER, Marhefka SL, Baker EA, Kolar S, Ebbert-Syfrett J, et al. Cognitive and emotional responses to human papillomavirus test results in men. Am J Health Behav. 2012;36(6):770–85.

-

Hansen RP, Vedsted P, Sokolowski I, Søndergaard J, Olesen F. Time intervals from first symptom to treatment of cancer: A cohort study of 2,212 newly diagnosed cancer patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:1–8.

-

Allgar VL, Neal RD, Ali N, Leese B, Heywood P, Proctor G, et al. Urgent GP referrals for suspected lung, colorectal, prostate and ovarian cancer. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(526):355-62.

-

Helsper CCW, van Erp NNF, Peeters PPHM, de Wit NNJ. Time to diagnosis and treatment for cancer patients in the Netherlands: Room for improvement? Eur J Cancer. 2017;87:113-121.

-

Turagabeci AR, Nakamura K, Kizuki M, Takano T. Family structure and health, how companionship acts as a buffer against ill health. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 200723;5:61.

-

Basu A, Ghosh D, Mandal B, Mukherjee P, Maji A. Barriers and explanatory mechanisms in diagnostic delay in four cancers – A health-care disparity? South Asian J Cancer. 2019;8(4):221-225.

-

Pudrovska T, Anishkin A. Clarifying the positive association between education and prostate cancer: a Monte Carlo simulation approach. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34(3):293-316.

-

Albano JD, Ward E, Jemal A, Anderson R, Cokkinides VE, Murray T, et al. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(18):1384-94.

-

Spiegel D. Cancer and depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;168(30):109-16.

-

Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415.

-

Goodwin JS, Zhang DD, Ostir GV. Effect of depression on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older women with breast cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):106-11.

-

Ciobanu AM, Roşca T, Vlădescu CT, Tihoan C, Popa MC, Boer MC, et al. Frontal epidural empyema (Pott’s puffy tumor) associated with Mycoplasma and depression. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55(3 Suppl):1203-7.

-

O’Rourke RW, Diggs BS, Spight DH, Robinson J, Elder KA, Andrus J, et al. Psychiatric illness delays diagnosis of esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21(5):416-21.