Considering the large number of caesarean section surgical procedures in Romania and the fact that we have encountered in our practice several cases of this pathology, at various gestational ages, which have posed special problems to solve, we consider that a guideline for the diagnosis and treatment would be useful, this being the objective of our article.

Sarcina implantată pe cicatricea operaţiei cezariene: propunere a unui ghid de practică medicală pentru diagnostic şi tratament

Caesarean scar pregnancy: proposed guidelines for diagnosis and management

First published: 20 decembrie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.69.4.2021.5771

Abstract

Rezumat

Având în vedere numărul mare de intervenţii chirurgicale de tipul operaţiei cezariene în România şi faptul că am întâlnit în practica noastră mai multe cazuri aparţinând acestei patologii, la diverse vârste gestaţionale, care au pus probleme deosebite, considerăm că un ghid pentru diagnosticul şi tratamentul acestei forme de sarcină ectopică ar fi de folos, acesta fiind obiectivul lucrării de faţă.

Introduction

Incidence of caesarean scar pregnancy

The actual incidence of caesarean scar pregnancy is unknown. It is estimated to occur in 1/1800-1/2500 of all deliveries by caesarean section(1,2). It is estimated that 0.15% of pregnancies with a history of caesarean delivery will be followed by a caesarean scar pregnancy(3), 52% representing patients with a history of a single delivery by caesarean section.

The only known risk factor is the previous delivery by caesarean section, the risk increasing with the number of previous caesarean section surgical procedures and the presence of the caesarean scar defect!

According to the National Institute of Statistics, in 2020, 161,320 children were born, of whom, according to the frequency of caesarean section of 37%, almost 60,000 by caesarean section surgical procedure. This means that, considering a rate of caesarean delivery of 0.15%, we can expect about 90 caesarean scar pregnancies per year.

The problem is that, in the continuation of pregnancy to term, these cases might present serious complications, including a life-threatening risk for the mother and fetus.

Pathogenesis of caesarean scar pregnancy

The consequence of the post-caesarean scar is that of compromising the decidua basalis and the Nitabuch’s fibrinoid layer. These are normally a barrier which prevents the invasion of the trophoblast in the myometrium of the anterior lower uterine segment. In caesarean scar pregnancy, the scar area allows the placenta to attach deeply to the myometrium and often to exceed the myometrium, invading the nearby organs.

There are two types of implantations of caesarean scar pregnancy(4):

-

endogenic (implantation on the scar site) – the pregnancy develops in the uterine cavity, but with the implantation of the placenta on the scar site

-

exogenic (implantation in-the-niche) – the gestational sac, which is deeply embedded in the scar, can grow toward the urinary bladder or the abdominal cavity.

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnosis of caesarean scar pregnancy is based on the following:

-

history of previous delivery by caesarean section

-

positive pregnancy test

-

ultrasound (2D, 3D, Doppler)

-

MRI.

Standard 2D ultrasound and Doppler ultrasound are the most reliable and most often used means of diagnosis(5).

Transvaginal ultrasound should be done in order to visualize the entire uterus. The cervical canal must be visualized between the internal orifice of the cervix and the external orifice of the cervix. The uterine cavity is usually clearly visible because of the endometrium, which is echogenic, under the progestational stimulus of pregnancy.

To establish the diagnosis, five ultrasound criteria were described:

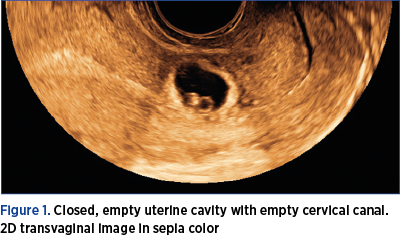

1. Closed, empty uterine cavity with empty cervical canal (Figure 1).

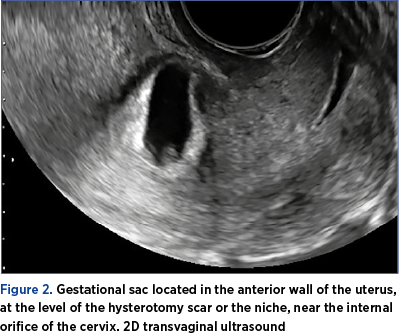

2. Localized gestational sac and/or placenta (Figure 2)

-

down in the anterior wall of the uterus, behind the urinary bladder

-

near the internal orifice of the cervix

-

at the level of the hysterotomy scar or in the niche.

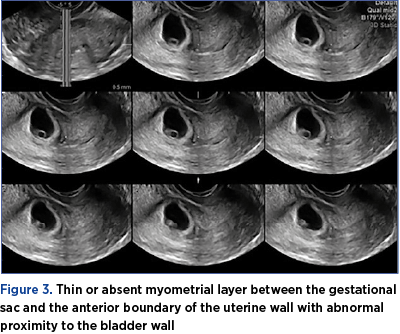

3. Thin or absent myometrial layer between the gestational sac and the anterior boundary of the uterine wall with abnormal proximity to the bladder wall (Figure 3).

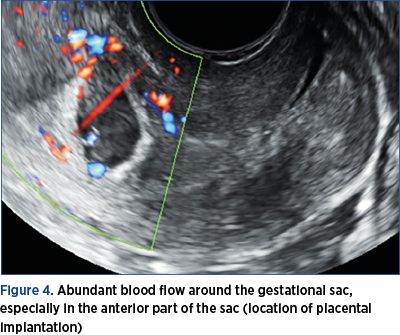

4. Abundant blood flow around the gestational sac, especially in the anterior part of the sac (location of placental implantation) – Figure 4.

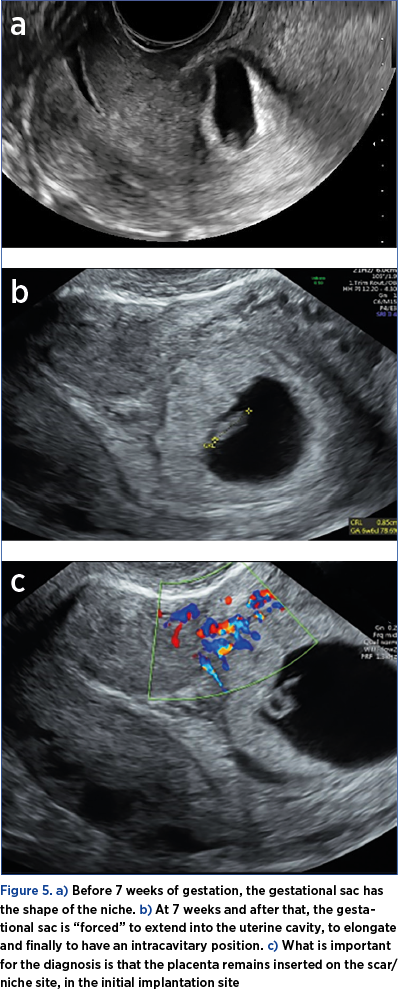

5. Before 7 weeks of gestation, the gestational sac has the shape of the niche. At 7 weeks and after that, the gestational sac is “forced” to extend into the uterine cavity, to elongate and finally to have an intracavitary position (Figure 5).

What is important for the diagnosis is that the placenta remains inserted on the scar/niche site, in the initial implantation site(7). The implantation site is highlighted by color Doppler ultrasound, which underlines the multiple vessels of the area, with rich, low resistance, and sometimes turbulent blood flow.

Differential diagnosis:

-

cervical pregnancy

-

ongoing miscarriage

-

low implantation of an intrauterine pregnancy.

Treatment

The first step is to determine the fetal cardiac activity(5).

A. If no vitelline and/or embryo duct and/or cardiac activity occurs, reexamination should be performed at every 2-3 days. If these elements still do not appear, ultrasound and biochemical follow-up are sufficient until the serum hCG values return to zero.

B. If cardiac activity is detected, there are two options:

-

continuation of pregnancy

-

termination of pregnancy.

The decision to continue the pregnancy is made only at the express request of the pregnant woman, who will be informed about the major risk of hemorrhage and rupture of the uterus, as well as the frequent need for puerperal hysterectomy.

Moreover, she must be informed about the risk of maternal mortality, which is not negligible, for pregnancies that have reached the age of fetal viability. Studies show a rate of 57% of live births and 63% of hysterectomies of necessity(6). It is imperative that the doctor make sure that the pregnant woman understands the risks and is willing to take them.

Termination of pregnancy

In the case of termination of pregnancy (the preferred option), the following are considered.

a) Major surgeries under general anesthesia:

-

laparotomy (hysterectomy or local excision)

-

laparoscopic, hysteroscopic or transvaginal surgery excision

-

dilation and curettage

-

aspiration abortion without cervical dilation.

b) Minimally invasive surgery: local injection of methotrexate (MTX), KCl, or vasopressin into the gestational sac.

c) Systemic medication with single or repeated doses of MTX and etoposide.

CAUTION! All these therapeutic maneuvers are performed in an equipped hospital with a surgical team capable of performing an emergency hysterectomy and an equipped intensive care team!

Recent studies on the reliability and effectiveness of these treatment methods have concluded:

-

uterine curettage is not recommended due to the major risk of bleeding (28%), hysterectomy of necessity and infertility (the results improve if preceded by uterine embolization – the risk of bleeding decreases to 4%)(8);

-

the systemic treatment with MTX should not be applied routinely, due to low efficacy, adverse effects, and decrease in fertility;

-

laparoscopic, open or hysteroscopic excision with defect repair is successful in 96% of cases and is associated with a relatively low bleeding risk (4%)(6).

The method considered perfect for asymptomatic cases, because it is not accompanied by hemodynamic disorders and preserves fertility, is the local administration of MTX in the gestational sac (under ultrasound or hysteroscopic guidance)(5,6). MTX injection into the gestational sac can be done abdominally or trancervically (used by us). An amniocentesis needle is used, which can be easily spotted by ultrasound. After methotrexate administration, b-hCG dosing is indicated at three days and ultrasound examination at five days.

In case of initiation of surgical abortion, aspiration of the ovular fragments is recommended to be practice (not abrasive curettage).

If significant bleeding occurs:

-

Foley balloon

-

vaginal balloon tamponade

-

hysterectomy of necessity.

We also used intramuscular methotrexate administration followed by uterine artery embolization combined with suction evacuation after 24-48 hours, as a conservatory approach for the treatment of seven patients diagnosed with caesarean scar pregnancy; suction evacuation took place with minimum blood loss and we have obtained one normal pregnancy after one year from a twin caesarean scar pregnancy treated by this protocol.

Organizational measures to prevent major accidents in this pathology

1. Any parturient woman who has delivered by caesarean section will be informed about the risks of a subsequent caesarean scar pregnancy (also mentioning the risk of maternal mortality in case of term evolution of such a pregnancy). It would be preferable for the postpartum discharge to be accompanied by written information on the steps to be taken before and in the event of a new pregnancy.

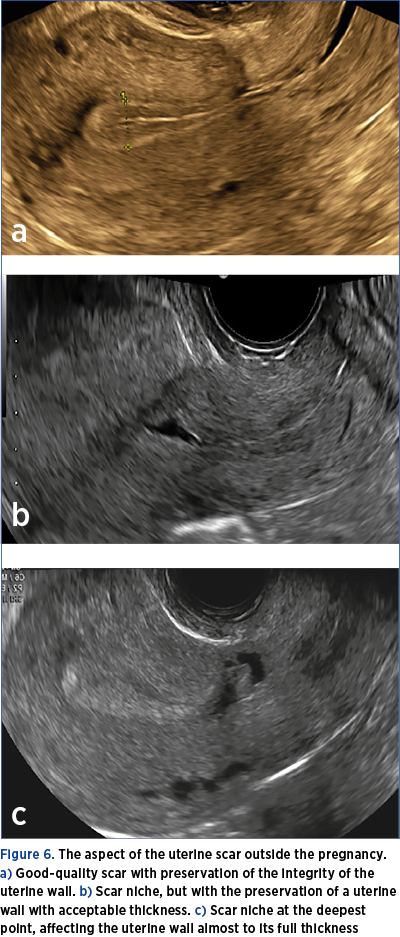

2. A transvaginal ultrasound will be indicated 6-8 months after delivery to assess the quality of the scar (Figure 6 a-c). This examination is very important, the risk determined by the implantation on the scar being high in the case of the caesarean scar niche.

3. In the event of a new pregnancy, the patient will be instructed to do the following:

a)Pregnancy test at a delay in menstruation of 7 days.

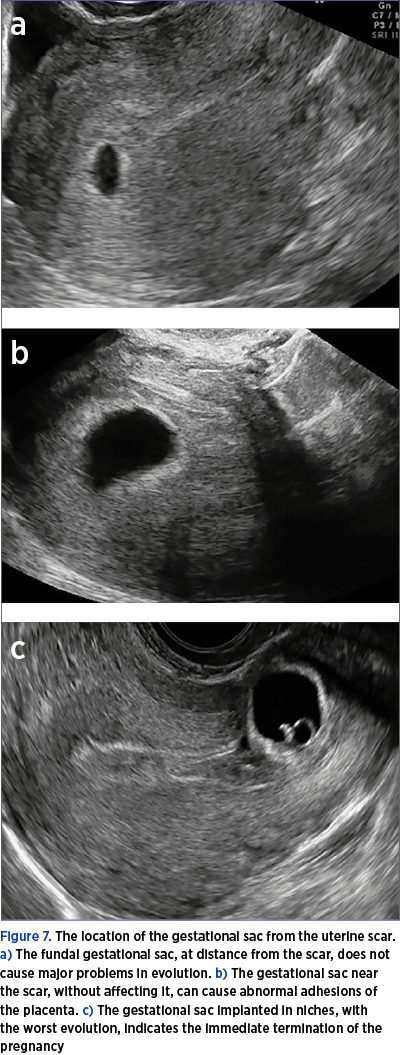

b)In case of a positive test, transvaginal ultrasound to identify the gestational sac and its location as early as possible (Figure 7).

4. In case of distance from the scar, the usual follow-up of the pregnancy (attention should be paid to the possibility of an abnormal insertion of the placenta – high risk).

5. In case of location at the level of the scar, there are two possibilities:

-

non-evolving pregnancy – follow-up (b-hCG, ultrasound)

-

evolving pregnancy.

In the case of an evolving pregnancy, the options will be presented to the patient:

a) Continuation of pregnancy (the risks will be underlined again and the patient will have to acknowledge her desire and knowledge of the risks in writing). The follow-up of the pregnancy and the delivery must take place in an equipped hospital, with third-level maternity, with a multidisciplinary surgical team and an equipped ICU service.

b) Termination of pregnancy, according to one of the methods presented before (as early as possible).

Considerations on the management of the third-trimester caesarean scar pregnancy

Consistent with the data in international literature, we emphasize that any caesarean scar pregnancy should be diagnosed early and terminated according to the protocol presented(9). We strongly recommend that the continuation of pregnancy is not encouraged in these circumstances and that the patients be referred to third-level obstetrics and gynecology services, preferably in multidisciplinary hospitals. The diagnosis of such a pregnancy in the first trimester must be accompanied by an explanation of the major risks of continuation of pregnancy, including the risk of maternal mortality. In case the pregnant woman’s option is the continuation of pregnancy, it is necessary to obtain a written informed consent, in which it should be clearly stated that the patient has understood the major risks to which she is subjected.

Currently, there are no guidelines or consensus on the continuation of pregnancy in this situation, or on the management of evolving caesarean scar pregnancy and at delivery.

There are two types of caesarean scar pregnancy(10):

-

Endogenous type 1 – the embryo grows progressively towards the uterine cavity, but the placenta is implanted on the scar. Although there is a major risk of bleeding and the placenta accreta is observed, the pregnancy may evolve to term with a live fetus.

-

Type 2 exogenous – the embryo embeds deep within the scar, where it develops and grows towards the urinary bladder and abdominal cavity, frequently causing uterine rupture, sometimes in the second trimester. This type requires immediate termination as soon as possible.

Analyzing the experience of other centers, we found 36 cases that have been left evolving and were cited in literature. Of these, 10 cases required hemostasis hysterectomy in the second trimester (27.8%), 26 live newborns were obtained at 26-39 weeks of gestation (72.2%), and hemostasis hysterectomy was performed in 17 cases (65.4%).

Thus, hemostasis hysterectomy was performed in 93.2% of cases(10-14).

Ultrasound is necessary to clarify the diagnosis, which must be performed with the urinary bladder almost full, to highlight the relationship of the placenta with the bladder wall. The ultrasound sign that shows the deep villous invasion in the placenta accreta is the so-called “rail sign” (defined as two parallel neovascularization vessels, evidenced in color Doppler, between the uterus-bladder junction and the bladder mucosa, with capillaries that interconnect with them)(15). MRI scan and possibly cystoscopy are also recommended to assess the invasion of the urinary bladder.

In the case of a full-term pregnancy, the following are considered:

-

scheduled caesarean section in an equipped hospital (third-level maternity), with ICU service skilled to resolve major obstetric hemorrhages and coagulation disorders;

-

the most experienced surgical team, including an obstetrician-gynecologist, a general surgeon and a urologist (with the possibility of calling a vascular surgeon and/or an interventional radiologist if necessary).

Caution! In these cases, surgery has major potential risks, the risk of maternal mortality being high!

Although there are no specific guidelines yet, ACOG and RCOG guidelines for placenta accreta, increta and percreta can be applied. Thus, the ACOG guidelines recommend an action plan in these cases, in which the third-trimester caesarean scar pregnancy is also included(9).

Preoperative

-

maximum increase of maternal hemoglobin values preoperatively

-

establishing a planned date of delivery

-

identifying the exact location of the delivery (operating room and its possibilities)

-

verifying that the necessary preoperative consultations have been performed

-

explaining to the patient and family that the transfer to a superior center might be necessary.

Intraoperative

-

checking if a surgical team with expertise in the field is available

-

checking the availability of intraoperative resources and their optimization for each case (e.g., hemosaver, emergency laboratory, adequate instruments, urological equipment)

-

checking the availability of other necessary services (e.g., interventional radiology)

-

coordination with the blood bank.

Postoperative

n ensuring that critical case care services are available and engaged in case care.

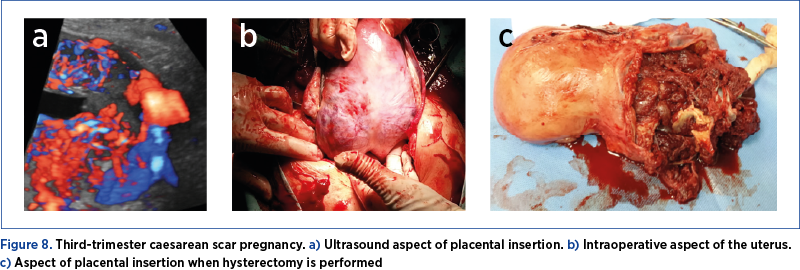

If case of an unforeseen situation and if the aspect of the uterus suggests this pathology (marked distension of the lower segment, the sign of caput medusae – Figure 8) and there are no circumstances that require immediate delivery, the case must be timed until the team with the best skills arrives. The intensive care unit (ICU) team must be alerted, general anesthesia must be performed, additional venous routes must be prepared, and blood and blood products are requested.

Patience from the first surgical team is the key, and action must not be taken until all the necessary conditions exist.

If the mobilization of surgical teams and the necessary resources are not possible, maternal and fetal stabilization and transfer of the pregnant woman to a specialized center will be considered(16).

From the point of view of the surgical technique, it is recommended to proceed as follows:

-

subumbilical midline laparotomy and, if necessary, supraumbilical midline laparotomy

-

transverse or median fundal hysterotomy with fetal extraction

-

the placenta stays in place without trying to detach it

-

the tranche of hysterotomy is closed and total hysterectomy is performed

-

the annexes are detached and the uterine pedicles are approached, which can be temporarily clamped

-

only after the temporary clamping of the uterine arteries does the bladder detachment start

-

hysterectomy should be total to avoid cervical bleeding, which is common in these cases.

Due to the extensive development of vascularization and anatomical changes, the surgery is difficult and requires experienced surgeons in pelvic surgery. As urinary bladder lesions occur frequently, the presence of an urologist is usually necessary and ureteric catheterization is recommended(17).

Conclusions

Third-trimester caesarean scar pregnancy is one of the worst obstetric situations, with a high maternal mortality risk, and requires highly qualified staff and special surgical, along with ICU resources.

In case a caesarean scar pregnancy evolving in the second or third trimester is discovered or in the case this situation exists because this was the patient’s express request, we recommend the emergency referral to a third-level maternity, located in a multidisciplinary hospital!

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. Cesarean scar pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:310.

- Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D. Placenta accreta: pathogenesis of a 20th century iatrogenic uterine disease. Placenta. 2012;33:244-251.

- Seow KM, Hwang JL, Tsai YL, Huang LW, Lin YH, Hsieh BC. Subsequent pregnancy outcome after conservative treatment of a previous cesarean scar pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:1167-1172.

- Miller R, Timor-Tritsch I, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine consult series #49 on cesarean scar pregnancy. Contemporary OB/GYN Journal. 2020;65(06).

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Santos R, Tsymbal T, Pineda G, Arslan AA. The diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of cesarean scar pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:44.e1-e13.

- Maheux-Lacroix S, Li F, Bujold E, Nesbitt-Hawes E, Deans R, Abbott J. Cesarean Scar Pregnancies: A Systematic Review of Treatment options. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(6):915-925.

- Pedraszewski P, Wlazlak E, Panek W, Surkont G. Cesarean scar pregnancy – new challenge for obstetricians. J Ultrason. 2018 Mar;18(72):56-62.

- Qiao B, Zhang Z, Li Y. Uterine Artery Embolization Versus Methotrexate for Cesarean Scar Pregnancy in a Chinese Population: A Meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23(7):1040-1048.

- Abraham RJ, Weston MJ. Expectant management of a Cesarean scar pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32:695-696.

- Zosmer N, Fuller J, Shaikh H. Natural history of early first trimester pregnancies implanted in Cesarean scars. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:367-375.

- Herman A, Weinraub Z, Avrech O. Follow up and outcome of isthmic pregnancy located in a previous Cesarean section scar. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:839-841.

- Sinha P, Mishra M. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a precursor of placenta percreta/accreta. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;32:621-623.

- Michaels AY, Washburn EE, Pocius KD. Outcome of cesarean scar pregnancies diagnosed sonographically in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:595-599.

- Tamada S, Masuyama H, Maki J, Eguchi T, Mitsui T, Eto E, Hayata K. Successful pregnancy located in a uterine cesarean scar: A case report. Case Rep Women Health. 2017 Apr;14:8-10.

- Jin-Chung S, Kang J, Shang-Ji T, Jen-Kuang L, Kao-langl I, Kuang-Ying H. The “rail sign”: an ultrasound finding in placenta accreta spectrum indicating deep villous invasion and adverse outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(3):229.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, Masheter C, Soisson AP, Dodson M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:331-7.

- ACOG Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Obstetric Care Consensus. Number 7 (Replaces Committee Opinion No. 529, July 2012. Reaffirmed 2021). (Accessed on 20.10.2021).

- RCOG Guidelines. Case Rep Womens Health. 2017 Apr;14:8-10.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Management of placenta praevia percreta – a case report

Placenta percreta is a severe obstetrical condition of the placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), associated with a high rate of maternal morbidity and m...

Care este rolul histerectomiei în tratamentul prolapsului organelor pelviene?

Prolapsul organelor pelviene (POP) este o afecţiune cu o rată de incidenţă în creştere, afectând mai mult de 40% din femeile de peste 50 de ani. Ex...

Fetal isolated vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation with spontaneous complete regression – a rare occurrence

Vein of Galen aneurysmal malformation (VGAM), also known as vein of Galen aneurysm, is a rare abnormality of the fetal cerebral vascular system, wi...

Locul chirurgiei în protocoalele actuale de tratament al cancerului de col uterin

Cancerul de col uterin este cel mai cunoscut cancer al femeii, dar şi al patrulea ca incidenţă în toată lumea. În marea majoritate a cazurilor, apa...