Sindromul hiperemezei induse de canabis – o entitate mai puţin cunoscută

An underrecognized condition – cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS)

Abstract

Cannabis or cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is a puzzling medical condition likely to become increasingly common on the emergency and oncology wards due to growing favorable public opinion about cannabis benefits and with the continued liberalization of the cannabis laws at local and national levels. CHS is related to the chronic use of cannabis and is defined by a triad of recurrent intractable vomiting, abdominal pain and frequent hot bathing. The risk factors, the clinical presentation, including the diagnostic criteria proposed by Simonetto et al. in 2012, as well as the CHS treatment are all displayed in this review article. Patients with CHS are frequently reporting to the hospital where extensive and expensive testing may be ordered, further increasing their physical and psycho-emotional suffering. Therefore, an early and accurate diagnosis is imperative to minimize both the healthcare expenses and the patients’ hardship.Keywords

cannabiscannabis hyperemesis syndromerisk factorsdiagnosissymptomscyclical vomitinghot bathingtreatmentRezumat

Sindromul de hiperemeză canabinoidă este o condiţie medicală complexă, a cărei prezenţă începe să fie sesizată din ce în ce mai frecvent la pacienţii internaţi în secţiile de urgenţă şi de oncologie. Aceasta se explică atât prin promovarea efectelor benefice ale canabisului, cât şi prin liberalizarea la nivel naţional şi internaţional a legilor care privesc directa utilizare a acestuia. Sindromul de hiperemeză canabinoidă este asociat cu consumul abuziv şi îndelungat de canabis şi este definit printr-o triadă simptomatică cuprinzând vărsături violente şi intermitente, dureri abdominale şi necesitatea frecventă de băi fierbinţi. Acest articol discută factorii de risc, prezentarea clinică, criteriile de diagnostic propuse de Simonetto et al. în 2012, precum şi tratamentul sindromului de hiperemeză canabinoidă. Pacienţii cu această simptomatologie se prezintă în mod frecvent la spital, unde li se efectuează teste medicale amănunţite şi costisitoare, care de fapt le-ar putea amplifica suferinţa fizică şi psihoemoţională. Un diagnostic precoce şi precis este esenţial în diminuarea atât a cheltuielilor de asistenţă medicală, cât şi a disconfortului creat pacienţilor.Cuvinte Cheie

canabissindromul de hiperemeză canabinoidăfactori de riscdiagnosticsimptomevărsăturibăi fierbinţitratamentCase presentation

Specific demographic data may have been altered to protect patient privacy. These alterations do not affect the educational value of the case.

Ms. B.P. is a 68-year-old African American female with a past medical history significant for breast cancer, treated at the age of 64 years old with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lumpectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy. She also suffered from morbid obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3, and osteoarthritis. She resides in California (USA), a state that at the time of her presentation had recently legalized and licensed recreational cannabis dispensaries through the formation of the California Bureau of Cannabis Control.

She presented to her local emergency department with approximately twelve hours of progressively worsening, cyclic nausea and vomiting. During her interview and examination, she was markedly distressed and in pain, not able to tolerate lying still in the gurney and frequently sitting up with a sensation that she needed to vomit. Computed tomographic (CT) imaging did not suggest any intraabdominal pathology. Laboratory studies were consistent with her prior diagnoses of CKD and type 2 diabetes mellitus and did not suggest an infectious source of the patient’s gastrointestinal complaints. Diabetic ketoacidosis was not present and blood alcohol level was undetectable. Urinalysis revealed glucosuria, but no evidence of infection. The patient denied any recent sick contacts and no other family members had similar complaints. The patient denied any recent travel history. The patient denied any problem with alcohol use, smoking or use of illicit substances. Medication reconciliation included NPH insulin, metoprolol, valsartan and acetaminophen (paracetamol) with hydrocodone. The patient also noted the use of an “over-the-counter” topical ointment that she used regularly for her arthritis pain, though she could not recall the brand name or active ingredient. Initially, nausea and associated anxiety were controlled in the emergency department with intravenous ondansetron and lorazepam, respectively.

As the underlying cause of the patient’s vomiting could not be determined while in the emergency department, she was admitted for observation. Upon rounding the subsequent morning, the resident assigned to the case noted that the patient had a sudden improvement in her subjective report of nausea. When asked what might have contributed to her change in symptoms, the patient stated that none of the medications truly improved her sensation of nausea. However, that morning the patient insisted on being allowed to shower as she had been vomiting all night and wanted to “freshen up”. She described how she immediately felt an improvement in her nausea and was reluctant to leave the shower.

At this time, a urine toxicology screen was ordered which suggested the presence of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) compounds in addition to hydrocodone. The patient was asked if she was using any cannabis or marijuana through smoking, vaping, edible, tincture or topical means. The patient denied the use of marijuana, though admitted that she knew members of her family were users. Her granddaughter was present at the time of this questioning and remarked that the over-the-counter ointment the patient had been using for arthritis was purchased at a dispensary by the patient’s grandson, who was a frequent cannabis consumer. The granddaughter and the patient assumed that the ointment only contained cannabidiol (CBD). Further discussion with the patient’s grandson revealed that he had purchased an ointment that contained equal measures of THC and CBD, thinking that it would be tolerated in the same way his grandmother had tolerated the “marijuana pill” (i.e., dronabinol) she had taken while she was undergoing cancer therapy. The patient was unaware that the product had contained THC and had increased her use to 4 to 5 times per day in the past two weeks due to the cold weather worsening her arthritis pain. As the vomiting worsened, she was also in more pain due to retching and had further increased her use of the ointment.

For nausea and pain control, the patient was offered a capsaicin-containing arthritis cream to apply to her abdomen. She was advised to use only products containing low doses of CBD in the future and to refrain from ingesting any other cannabis containing products. She was discharged from the hospital without complaint the following day.

Introduction

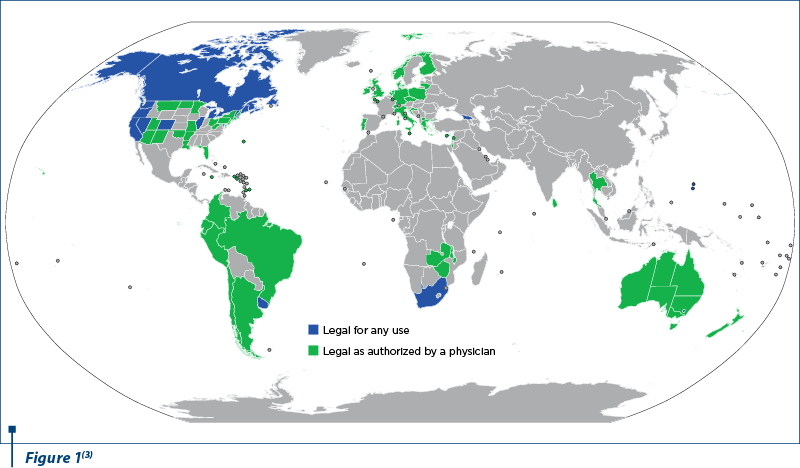

Cannabis and cannabis-derived products are increasingly making their way on the medical, recreational and illicit markets. Cannabis can be used in smoked, vaporized or in oil extract form. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, it was the most commonly used drug worldwide in 2016(1). A colloquial term for cannabis is marijuana, promoted as a pejorative in the early days by United States law enforcement personnel as a substance used by non-whites, particularly individuals of Mexican descent living in the United States(2). While initially classed as a banned substance, several countries have since legalized the use of cannabis products for medical and/or recreational purposes.

Currently, 33 American states, the District of Columbia, and the territories of Guam, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands have legalized cannabis use for medical purposes. Fourteen other states have authorized the use of the same product for recreational intent(2).

Anecdotally, cannabis has been purported to have benefits in controlling various symptoms common amongst cancer patients, including neuropathic pain and chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting. More empiric research to support these historical observations is ongoing as scientific and financial interest in cannabinoid compounds increases. Patients with cancer have sought access to these products from illicit dealers for decades and are now more than ever requesting authorization from their physicians for medical waivers. Oncologists, palliativists and especially emergency medicine physicians, regardless of their country of practice, should familiarize themselves with cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (CHS), one of the most commonly encountered syndromes related to chronic cannabis use(4).

Definition

Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome was first described in 2004 by Allen et al. as a paradoxical condition secondary to prolonged use of high doses of cannabis. It is characterized by a triad of:

1. Cyclic episodes of nausea and vomiting.

2. Abdominal pain.

3. Frequent use, even compulsive hot bathing(4).

Risk factors

Most common risk factors discussed in literature include:

-

Young age, with a prevalence increase to 15% in 2005, from 5% in 1990(4).

-

Male gender(4).

-

Socioeconomic status. There is discordance within the literature, suggesting that certain members of high-income and low-income groups are both more likely to report the heavy cannabis use that tends to be more frequently associated with CHS(4,5).

-

Race, with a study indicating that non-Hispanic white patients are at higher risk of developing severe vomiting related to cannabis use(5).

-

Daily use of marijuana(4,6).

-

High doses of cannabis, exceeding 3 to 5 times per day, with some users admitting to smoking 2000 mg of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) per day.

-

Increases in the THC:CBD ratio in cannabis strains and products over time(5,6).

-

Prolonged use, of 2-10 years(1,5,6).

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of CHS is unknown, but many articles suggested a multifactorial etiology. Several hypotheses have been circulating:

1. Dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system, leading to loss of control over nausea and vomiting by chronic overstimulation of this system. Cannabis acts primarily on the CB1 receptors located in the central nervous and gastrointestinal systems and CB2 receptors located in the periphery. The CB1 receptors found in the central nervous system (cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, hippocampus and cerebellum) are responsible for the feelings of euphoria, whereas the same receptors in the gastrointestinal tract are involved in gastrointestinal secretion and motility, as well as inflammation. CB2 receptors are located in the peripheral lymphatic system and they are more involved in inflammation and in the immune responses(1,4-7).

2. Dysregulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is activated when the body is confronted with stress. CB1 receptors are promoting recovery from stress by inhibiting the THA axis. This may be one mechanism underlying the anxiolytic effects of cannabis(6,8).

3. Dysregulation of the splanchnic nervous system that contributes to the innervation of the internal organs by providing both visceral sympathetic and sensory fibers (with the exception of the pelvic splanchnic system that carries parasympathetic and sensory fibers). This nervous system is responsible for the gastrointestinal peristalsis and local vasodilation and it contains cannabinoid CB1 receptors that, as mentioned before, are involved in the enteric secretion, motility and inflammation(6,7).

4. THC accumulation in the fatty tissue. THC represents the major active ingredient of cannabis and has a prolonged half-life. It is highly lipophilic and, as a result, it accumulates in the adipose tissue where it is released from during periods of stress or fasting. Subsequently, large THC deposits in the adipose tissue could produce a phenomenon of “reintoxication” while under stress or fasting(4,7).

5. CBD, which is a non-euphoric cannabinoid present in both intoxicating cannabis strains and commercial hemp, has antiemetic effects at low doses, but may have proemetic effects at high doses(7,8).

6. Potential cannabis – drug interactions at the CYP 450 cytochrome levels. THC and CBD levels could be elevated if cannabis is used in combination with CYP450 inhibitors such as azoles, some macrolides, amiodarone, fluoxetine or modafinil, to name just a few. Conversely, THC and CBD levels could be lowered if used together with CYP inducers like barbiturates, carbamazepine, phenytoin, dexamethasone or rifampin(9).

Clinical presentation

In 2012, Simonetto et al. have proposed the diagnosis criteria for CHS, as listed below.

1. Essential for diagnosis:

-

Long-term cannabis use.

2. Major features:

-

Cyclic nausea and vomiting with patients experiencing 12-15 episodes of vomiting per day. These episodes may last for 24-48 hours at a time and they are interrupted by asymptomatic periods that may last for weeks or even months. Some patients may present with a combination of screaming and loud vomiting, symptom known as “scromiting”. The CHS nausea and vomiting are resistant to typical antiemetics(10,11).

-

Symptom resolution with cannabis cessation.

-

Symptom relief by a “pathologic bathing behavior” (prolonged hot baths or showers). The compulsive hot showering or bathing may be encountered in 90-100% of the cases and may be explained by the fact that hot water promotes peripheral vasodilatation and thus diverts the blood circulation from the splanchnic system to the muscles and skin. The hotter the water, the more pain relief patients may perceive, and symptoms may restart the moment the body temperature starts dropping. Some patients may spend almost half of their day bathing or showering(6,9,11).

-

Abdominal pain with epigastric and periumbilical location.

-

Weekly use of marijuana.

3. Supportive features:

-

Age of patients: less than 50 years old.

-

Unintentional weight loss of >5 kg.

-

Tendency to experience the symptoms in the morning.

-

Normal bowel habits.

-

Negative laboratory, radiographic and endoscopic test results(11-14).

-

The presentation of CHS can be divided in three phases: prodromal, hyperemetic and recovery (Table 1). The prodromal phase usually lasts for months to years, the hyperemetic phase appears in a cyclical fashion lasting for a few days and repeating itself every few weeks or months and, finally, the recovery phase lasts for days to months(4,7).

Evaluation

Patients reporting to the emergency rooms usually receive an extensive diagnostic workup, including laboratory and imaging studies, that typically are unrevealing and, subsequently, CHS remains misdiagnosed. Some studies showed that the average number of visits to the emergency room prior to the diagnosis of CHS was 7.1, with a time delay from the onset of symptoms to the moment of diagnosis of about 4.1 years(11).

The two main reasons for this significant delay seem to be the patients’ hesitancy in revealing their use of cannabis and the close resemblance of the CHS with other pathologies. The patients may fear either social stigma related to their cannabis use or legal repercussions in countries where cannabis consumption is punishable by law, therefore a non-judgmental attitude is essential during the interview and physical examination.

The initial evaluation of these patients includes:

-

Complete blood count (CBC) that may be normal or show some anemia.

-

Metabolic panel (BMP or CMP) that could reveal signs of dehydration in the form of prerenal azotemia with low serum bicarbonate and acidosis.

-

Urinalysis that could show ketones as markers of the patient’s nutritional status.

-

Pregnancy test that is required for all women of fertile age.

-

Urine drug screen showing the presence of THC is essential for the diagnosis. Discussions about cannabis use should take place only after receiving the confirmatory testing with gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC-MS) because some foods containing hemp and several drugs such as dronabinol (Marinol®), efavirenz (Sustiva®), non-steroidal antiinflammatories (NSAIDs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) could cause false positive results on urine toxicology screens.

-

Plain radiographic series(1,4,5,7,10,11).

Some patients may undergo computer tomographic scans, magnetic resonance imaging or esophagogastroduodenoscopy that may be perfectly normal or showing some Mallory-Weiss lesions, esophagitis or gastritis from the repeated vomiting(10,13).

Differential diagnosis

Several medical conditions should be included in the differential diagnosis of CHS:

1. Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS), an idiopathic disorder affecting both adults and children, exhibiting a similar symptomatology (recurrent bouts of vomiting with 12-15 episodes of vomiting per day alternating with periods of normal health). However, these symptoms are unrelated to cannabis use and most of the patients do not experience compulsive bathing. CVS is often inappropriately considered responsible for patients’ symptoms if the clinicians neglect to ask about the chronic use of cannabis(4,7,11,13,14).

2. Psychogenic vomiting related to increased life stressors that seem to affect more frequently women(14).

3. Abdominal migraines that may start in childhood and tend to be accompanied by migraine headaches in adulthood. The symptoms are sometimes triggered by the same foods inducing migraine headaches such as chocolate, cheese and monosodium glutamate. Triptans may help in alleviating these symptoms(14).

4. Bulimia with a binging/purging behavior(13).

5. Hyperemesis gravidarum.

6. Addison disease secondary to partial or total failure of the adrenocortical function that presents with weight loss, nausea, vomiting, hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia and skin hyperpigmentation(14).

7. Gastroparesis in diabetics or in patients placed on opioids for cancer pain control(13).

8. Gastritis or peptic ulcer disease.

9. Pancreatitis.

10. Bowel obstruction.

Treatment

Several approaches have been favored in the management of CHS:

Abstinence from cannabis, which is essential in the resolution of the CHS symptoms. Patients need to be interviewed in a nonjudgmental way about their use of licit or illicit substances and they also may require extensive counseling about it. They should be informed that cannabis is the causative factor for their symptoms and that these symptoms will return if they revert to their cannabis use. Cognitive behavioral therapy, contingency management and motivational enhancement therapy have been used with some success. A multidisciplinary approach is sometimes required especially for the chronic regular users who are less willing to abstain from cannabis. Marijuana Anonymous, that uses the same 12 Steps of recovery program like Alcoholic Anonymous, could be employed as well(1,4,13,15,16).

Supportive treatment involves vigorous rehydration with intravenous fluids and correction of electrolyte imbalances, as well as the management of marijuana withdrawal. The withdrawal symptoms such as disruptions of sleep, appetite and mood usually resolve in about two weeks after discontinuing the cannabis. Cannabis derivatives such as dronabinol or nabiximols, gabapentin, lithium along with zolpidem and benzodiazepines for sleep could be used. Proton pump inhibitors are indicated if gastritis and/or esophagitis are present(4,7,9,13).

Haloperidol 5 mg or olanzapine 5-10 mg intravenously or intramuscularly are unconventional antiemetics that could also be used for chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting. One study showed the resolution of the aforementioned symptoms within one hour after administration(10,16). A retrospective study reporting the usage of droperidol in 689 medical records revealed a lower median length of stay and less use of antiemetics in the droperidol group(17). EKG monitoring is indicated in some patients with electrolytes imbalance, knowing that hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia and antipsychotics could all potentially prolong the QT interval(6,13).

Capsaicin cream applied to the abdomen was successfully employed in the treatment of CHS symptoms. Capsaicin’s antiemetic effect most likely involves the activation of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), receptors that are decreasing the activation of the vomiting center located in the medulla. Capsaicin is inexpensive, readily available over-the-counter and fast acting, with symptom resolution in 45 minutes after application(1,7,11,13,18).

Benzodiazepines have been recommended by some as the first line of treatment, based on their anxiolytic and antiemetic effects. Studies have reported a remarkable relief in nausea and vomiting in patients with CHS after being administered a benzodiazepine like lorazepam(4,6,11).

Antiemetics such as 5-HT3, D2, H1 and neurokinin 1 receptor antagonists are quite ineffective, considering that one of the CHS characteristics is the resistance to the mainstay antiemetics(4,10,13).

Opioids are not effective and their use is discouraged due to their gastrointestinal side effects, particularly nausea, vomiting, constipation and gut dysfunction(6,16).

Prognosis

The prognosis of CHS is generally good with timely diagnosis and patients’ acceptance of their need to discontinue the use of cannabinoid products. Relapses may occur quickly if the patient does not refrain from using cannabis. It is essential for providers to counsel their patients in a nonjudgmental fashion to foster trust in the diagnosis and the need to discontinue cannabis use; many patients may be resistant to this recommendation due to a strongly held belief that cannabis treats – rather than causes – nausea.

Conclusions

Increased efforts need to be invested in the education of both clinicians and patients regarding cannabis use disorders, including the unique and paradoxical CHS.

Patients need to be informed that cannabis is responsible for their symptoms and that CHS is a paradoxical condition related to their chronic use of cannabis. Some patients, especially the ones resistant to the idea of quitting their habits, may require a multidisciplinary team approach.

With cannabis becoming increasingly popular for both therapeutic and recreational purposes, clinicians must be prepared to interview their patients about their use of legal or illegal substances and to address cannabis use disorders with a balanced, patient-first approach. An early and accurate diagnosis of CHS will limit the need for hospitalization and reduce unnecessary testing.

Additionally, prompt recognition of this medical condition is essential to palliate the physical and emotional suffering of the patients who often have resorted to cannabis as a treatment for their persistent nausea and vomiting. The lack of accurate diagnosis can create a vicious cycle in which their symptoms are worsened by continued consumption of the drug they think should help. Therefore, CHS should be considered whenever treating patients with suspected long-term cannabis use and experiencing recurrent nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain relieved by hot showers or baths(7,12).

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Knowlton MC. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Nursing. 2019 Oct; 49(10):42-45.

- Anthony JC, Lopez-Quintero C, Alshaarawy O. Cannabis Epidemiology: A Selective Review. Curr Pharm Des. 2017 Jan 4; 22(42):6340-6352.

- By Jamesy0627144 - Derived from BlankMap-World.svg and BlankMap-World6-Subdivisions.svg., CC BY-SA 4.0. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71821752

- Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011 Dec; 4(4):241-9.

- Madireddy S, Patel RS, Ravat V, Ajibawo T, Lal A, Patel J, Patel R, Goyal H. Burden of Comorbidities in Hospitalizations for Cannabis Use-associated Intractable Vomiting during Post-legalization Period. Cureus. 2019 Aug 27; 11(8):e5502.

- Pizarro-Osilla C. What is Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome. J Emerg Nurs. 2018 Nov; 44(6):665-667.

- Pergolizzi Jr JV, LeQuang JA, Bisney JF. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis. Med Cannabis Cannabinoids. 2018;1:73–95.

- Parker LA, Kwiatkowska M, Burton P, et al. Effect of cannabinoids on lithium-induced vomiting in the Suncus murinus (house musk shrew). Psychopharmacology. 2004; 171, 156–161.

- Howard I. Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome in Palliative Care: A Case Study and Narrative Review. J Palliat Med. 2019 Oct; 22(10):1227-1231.

- Randall K, Hayward K. Emergent Medical Illnesses Related to Cannabis Use. Mo Med. 2019 May-Jun; 116(3): 226–228.

- Chocron Y, Zuber JP, Vaucher J. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. BMJ. 2019 Jul 19; 366:l4336.

- Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, Szostek JH. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis: A Case Series of 98 Patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Feb; 87(2): 114–119.

- Stinnett VL, Kuhlmann KL. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: An Update for Primary Care Providers. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2018 Jun; Volume 14, Issue 6, 450-455.

- Lua J, Olney L, Isles C. Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome: still under recognised after all these years. JR Coll Physicians Edinb. 2019 Jun; 49(2):132-134.

- Venkatesan T, Hillard CJ, Rein L, Banerjee A, Lisdahl K. Patterns of Cannabis Use in Patients With Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jul 25; DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.039.

- Sorensen CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, Phillips KT, Monte AA. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment – a Systematic Review. J Med Toxicol. 2017 Mar; 13(1): 71–87.

- Lee C, Greene SL, Wong A. The utility of droperidol in the treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Clinical Toxicology. 2019; 57(9), 773-777.

- Wagner S, Hoppe J, Zuckerman M, Schwarz K, McLaughlin J. Efficacy and safety of topical capsaicin for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome in the emergency department. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019 Sep 4; 1-5, doi: 10.1080/15563650.2019.1660783.