Adrenocortical carcinoma in children is a rare tumor developed from the adrenal cortical cells. A very important step in the diagnosis process is represented by the tumor biopsy and the immunohistochemical exam of the resection piece, adding the molecular analysis. The suggestive findings for the diagnosis are: abdominal or suprarenal gland mass, virilization syndrome, Cushing or adrenogenital syndrome and primary hyperaldosteronism with secondary hypertension. We present the case of a 13-year-old boy who was diagnosed in our clinic with adrenocortical carcinoma and who had a fatal evolution in only 18 days, in the context of metastatic tumor complicated with malignant hypertension.

Carcinomul corticosuprarenal – evoluţia fatală a unui tip rar de cancer la copil

Adrenocortical carcinoma – fatal evolution of a rare cancer in children

First published: 03 decembrie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.64.4.2021.5793

Abstract

Rezumat

Carcinomul corticosuprarenal la copii este o tumoră rară, dezvoltată din celulele corticale suprarenale. Un pas foarte important în procesul de diagnostic este reprezentat de biopsia tumorală şi de examenul imunohistochimic al piesei de rezecţie, completate de analiza moleculară. Elementele sugestive pentru diagnostic sunt: masă abdominală sau suprarenală, sindromul de virilizare, sindromul Cushing sau adrenogenital, hiperaldosteronismul primar cu hipertensiune arterială secundară. Prezentăm cazul unui băiat de 13 ani care a fost diagnosticat în clinica noastră cu adenocarcinom corticosuprarenal şi care a avut o evoluţie fatală în numai 18 zile, în context de tumoră metastazată pulmonar şi hepatic încă de la diagnostic, complicată cu hipertensiune arterială malignă.

Introduction

Adrenocortical carcinoma in children (ACC) is a rare tumor developed from the adrenal cortical cells. It represents 0.05-0.2% of all type of tumors, its peak of incidence being in the fourth decade of life and being responsible for 0.2% of all deaths from cancer(1). The incidence is 0.2–0.3 new cases per 1 million people/year worldwide(2). The clinical diagnosis is very difficult to make without key investigations such as CT scan, MRI, PET-CT scan and laboratory findings (blood glucose, cortisol, aldosterone, DHE-S, urinary and blood metanephrine, urinary measurement of homovanillic acid and vanilmandellic acid).

Case presentation

We present the case of a 13-year-old boy who was admitted in the oncology department for alteration of the general condition, large abdomen, dyspnea at small and medium efforts, nervousness and fatigue, symptoms that lasted for four weeks. The family took the child at the regional hospital where the ultrasound described a scratchy mass of about 105/100 mm, localized in the left upper side of the abdomen that may develop from the left kidney. They also took a CT scan that described: bilateral pulmonary nodules, around 1 cm, localized at the base of the lungs, that suggested secondary lesions, without any fluids in the pulmonary cavities. An extremely large tumor with heterogeneous appearance, with internal necrosis, compressed the proximity organs, of about 15/12 cm. The left renal vein could not be seen. There were many secondary lesions seen in the liver’s VII segment of about 6 cm diameter. The left corticosuprarenal gland could not be seen. The right kidney was normal. There was no fluid in the abdominal cavity. The right iliac crest had a heterogeneous aspect. For these reasons, the child was transferred to our department for further investigations and treatment.

The medical history of the patient mentions mental retardation since 2014. In the same time, he was diagnosed with precocious puberty. From some religious reasons, the family didn’t investigate further in this direction. No other chronical diseases were known by the patient’s mother. In the patient’s family, there were no genetical syndromes.

The clinical data at the moment of the admission: the general condition of our patient was severely altered, with plethoric face, cortisone-related acne (Figure 1), signs of early virilization (mustache, thoracic and axillary pilosity), stretch marks on his abdomen, superior limbs and on the thorax (Figure 2). The adiposity was asymmetrically distributed, especially in the abdominal area. No hepatosplenomegaly or lymph nodes were palpable. He had also high blood pressure (HBP), 150/100 mmHg, over the 97.5th percentile for height.

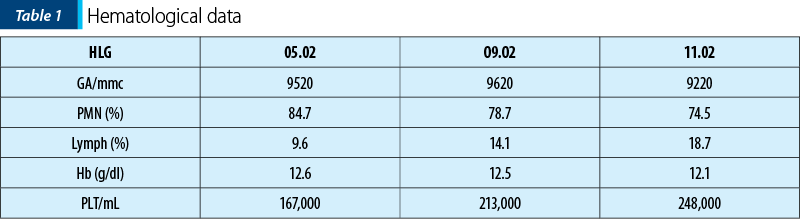

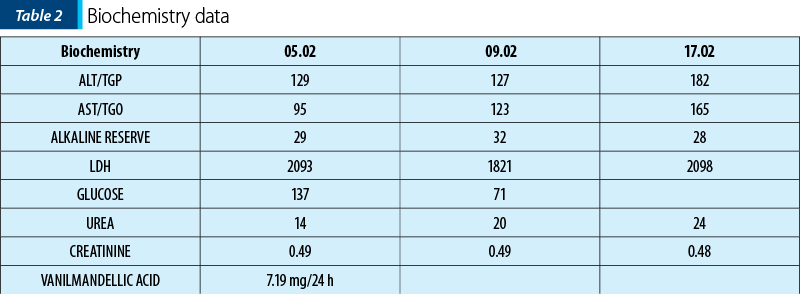

Biological data at the admission

At that point, we had five possible diagnostics:

-

Pheochromocytoma – based on HBP and the plethoric aspect of the patient.

-

Medullo or adrenocortical carcinoma – CT scan and the clinical aspect.

-

Adrenogenital syndrome – HBP and the precocious puberty.

-

Left kidney tumor with lung metastases – CT scan aspect.

-

Renal vein and superior vena cava thrombosis – CT scan aspect.

For the evaluation of heart impact of the HBP, we performed cardiac ultrasound that showed ascended heart, pushed by the tumor, with a normal structure, slightly concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), without pericardial fluid, with ejection fraction (EF) of 86%.

In the context of the existence of lung and liver metastases, we considered useful to make bone marrow aspiration which revealed richly cellulated pleomorphic aspect, with hyperplasic erythropoiesis, hypergranular elements in granulopoiesis, and normoplastic megakaryopoiesis with platelets in pile.

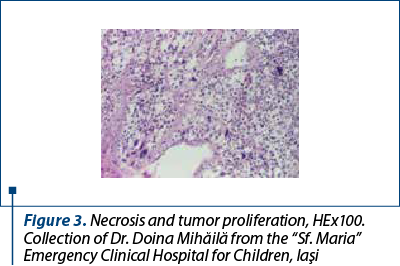

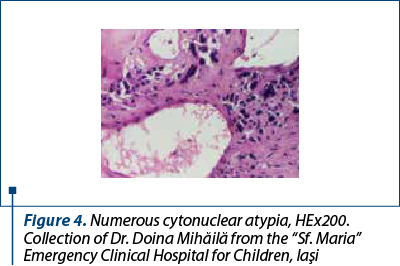

After a few days with a slight amelioration of the general status, we could perform a tumor biopsy which revealed corticosuprarenal gland carcinoma. In Figure 3, we present the typical aspect with necrosis and tumoral proliferation, in HE coloration, followed by the immunohistochemical exam which revealed the specific cellular marker for this type of tumor.

After these investigations, we had a certitude diagnosis: adrenocortical carcinoma in a child.

Unfortunately, the patient’s general condition deteriorated rapidly due to severe hypertension, developing signs of pulmonary vascular overload, which necessitated the transfer to the intensive care unit, with the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome, acute respiratory failure, and malignant hypertension. The patient performed a chest X-ray which showed accentuated and thickened intercleidohilar drawing, diffuse veiling of the left hemithorax and the diaphragmatic cost sinus. Heart displayed on the diaphragm with the transverse diameter increased at the expense of the lower left arch. The aspect was suggestive for acute pulmonary oedema.

Because of the poor general condition, with aggravating dyspnea, polypnea (30 respiration/min), tachycardia (144/min), malignant high blood pressure (200/144 mmHg), the patient was retransferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). He maintained the severe respiratory failure (SaO2 87-97%), but he suddenly developed heart failure, with hypotension (94/54 mmHg) and tachycardia (122-145/min). In the 18th day after admission, he suffered a cardiorespiratory arrest that did not respond to the resuscitation maneuvers.

The final diagnosis was left adrenocortical carcinoma, hepatic and lung metastases, cardiorespiratory failure, severe secondary high blood pressure, acute pulmonary edema, left pleurisy, renal and inferior vena cava thrombosis, severe mental retardation, early puberty. Due to the religious affiliation of the parents, necropsy evaluation was not possible.

Discussion

A very important step in the diagnosis process is represented by the tumor biopsy and the immunohistochemical exam of the resection piece, adding the molecular analysis (NGS panel for the genetical diagnosis). Suggestive findings for the diagnosis are: abdominal or suprarenal gland mass, virilization syndrome, Cushing or adrenogenital syndrome, primary hyperaldosteronism. Almost 50% of the adrenocortical carcinomas produce cortisol, aldosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone. The pathological diagnosis of adrenocortical carcinoma, still challenging for its rarity, is based on the recognition at light microscopy of at least three among nine morphological parameters, according to the Weiss scoring system, introduced 27 years ago(3). The metastatic disease is more common in children aged above 12 years old, and the most common sites of metastases are the liver and the lungs(4). In our case, the metastases were proven from the first moment, in the lung and liver, just like the literature mentions. There are some genetic syndromes recognized to determine CSC in children in their evolution. Li-Fraumeni syndrome is a rare condition in which the mutation of p53 gene can determine corticosuprarenal tumors. Beckwith-Widemann syndrome associates macroglossia, macrosomia, organomegaly, and sometimes mass formation (neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, hepatoblastoma, masses in the adrenal cortex). Another entity is familial adenomatous polyposis which implies multiple polyps localized in the large intestine mucous which can develop colorectal cancer and suprarenal gland tumors. The syndrome MEN1 implies parathyroid tumors, pancreatic tumors and pituitary gland tumors. In 30-50% of cases they can associate suprarenal gland masses and in some cases the masses are malignant(5). Unfortunately, in our case we didn’t have enough time to performed genetic studies, but the initial anamnesis didn’t confirm hereditary diseases in the family. The treatment consists in surgery – elective at the diagnosis (if possible), chemotherapy (doxorubicin, etoposide, cisplatin), arterial embolization, and radiotherapy(6). The rapid fatal evolution of our patient prevented the initiation of any specific oncological therapy, but the placement of the case in the final stage from the beginning, with systemic metastases, signed a severe prognosis.

Conclusions

Adrenocortical carcinoma is a very rare pediatric oncologic pathology, in association with early puberty and secondary severe untreated high blood pressure. The respiratory and vascular complications of the secondary high blood pressure, next to lung and liver metastases, made impossible the treatment of this case, with a fulminant evolution.

Acknowledgment: Our thanks go to Dr. Doina Mihăilă for her contribution in the preparation and interpretation of the biopsy, an essential step in the diagnosis of this case. Also, we want to thank Lecturer Bogdan Stana for his guidance in writing this paper.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

McAteer JP, Huaco JA, Gow KW. Predictors of survival in pediatric adrenocortical carcinoma: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program study. J Pediatr Surg. 2013 May;48(5):1025-31.

-

Grisanti S, Cosentini D, Laganà M, Turla A, Berruti A. Different management of adrenocortical carcinoma in children compared to adults: is it time to share guidelines? Endocrine. 2021 Dec;74(3):475-477.

-

Papotti M, Libè R, Duregon E, Volante M, Bertherat J, Tissier F. The Weiss score and beyond – histopathology for adrenocortical carcinoma. Horm Cancer. 2011 Dec;2(6):333-40.

-

Gupta N, Rivera M, Novotny P, Rodriguez V, Bancos I, Lteif A. Adrenocortical Carcinoma in Children: A Clinicopathological Analysis of 41 Patients at the Mayo Clinic from 1950 to 2017. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;90:8-18.

-

Wang JG, Mo DC. Regarding the Children’s Oncology Group ARAR0332 Protocol for Pediatric Adrenocortical Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Sep 20;39(27):3087-3088.

-

Rodriguez-Galindo C, Krailo MD, Pinto EM, Pashankar F, Weldon CB, Huang L, Caran EM, Hicks J, McCarville MB, Malkin D, Wasserman JD, de Oliveira Filho AG, LaQuaglia MP, Ward DA, Zambetti G, Mastellaro MJ, Pappo AS, Ribeiro RC. Treatment of Pediatric Adrenocortical Carcinoma With Surgery, Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection, and Chemotherapy: The Children’s Oncology Group ARAR0332 Protocol. J Clin Oncol. 2021 Aug 1;39(22):2463-2473.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Îmbunătăţirea motricităţii fine la copiii cu nevoi speciale utilizând terapia ocupaţională

Terapia ocupaţională încearcă să dezvolte calitatea vieţii oricărei persoane a cărei capacitate funcţională este limitată, acest obiectiv fiind...

Sleep-related breathing disorders in the pediatric patient with Prader-Willi syndrome

Sindromul Prader-Willi (PWS) este o boală genetică rară, întâlnită cu o incidenţă de 1:15000 de nou-născuţi, identificată la toate rasele şi car...

Evaluarea funcţională a tractului digestiv inferior la copii – manometria anorectală

Manometria anorectală este o metodă obiectivă utilizată pentru examinarea funcţiei anorectale şi a sensibilităţii rectale. Scopul acestui studiu ...

Provocările tratamentului stomatologic la copiii cu tulburări de spectru autist

În literatura de specialitate, unii autori folosesc termenul de „epidemie de autism”, care poate fi explicată de creşterea „conştientizării” priv...