Intestinal polyps are tumoral masses protruding in the gastrointestinal lumen, with various histopathological patterns, either as neoplastic or non-neoplastic type, and epithelial or non-epithelial type. The classical form of clinical presentation is rectal bleeding, with or without mucus, in a normal appearing stool, and only in a minority of cases there is lower abdominal pain. The standard procedure for diagnosis and management of pediatrics colorectal polyps is full colonoscopy. Recent studies have revealed high levels of fecal calprotectin in patients with intestinal polyps and modern sonography empowered the detection rate of colonic polyps before performing colonoscopy. We report the case of a 5-year-old boy who was refereed to our gastroenterology unit with a history of one month of intermittent rectal bleeding and mild abdominal pain, with an unremarkable medical history, and with normal physical and biochemical exam. The abdominal ultrasound showed abundant blood flow signal in a round pedunculated shaped intraluminal mass situated in the lower left abdomen area, measuring 20/15 mm. The colonoscopy revealed a pedunculated left colon polyp that was removed using electroresection. The aim of this report is to draw attention to the importance of hematochezia in children and to the need for adherence to actual guidelines regarding the endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract in children.

Sângerarea rectală la copii – prezentare de caz

Rectal bleeding in children – case report

First published: 03 decembrie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.64.4.2021.5794

Abstract

Rezumat

Polipii intestinali reprezintă mase tumorale proeminente în lumenul gastrointestinal, cu diverse aspecte histopatologice, de tip neoplazic sau non-neoplazic, epiteliale sau nonepiteliale. Forma clasică de prezentare clinică este sângerarea rectală, cu sau fără mucus, într-un scaun cu aspect normal şi doar în unele cazuri rare asociază şi durere abdominală. Procedura standard pentru diagnosticul şi managementul polipilor colorectali pediatrici este reprezentată de colonoscopia completă. Studii recente au evidenţiat niveluri ridicate ale calprotectinei fecale la pacienţii cu polipi intestinali, iar ecografia modernă a crescut rata de detectare a acestora anterior examinării endoscopice. Prezentăm cazul unui copil de sex masculin, în vârstă de 5 ani, adresat departamentului de gastroenterologie pediatrică, având un istoric de scaune cu sânge proaspăt debutate în urmă cu o lună, la care asociază şi dureri abdominale moderare, fără a avea un istoric medical remarcabil. Examenul clinic şi investigaţiile de laborator au fost în limite normale. Ecografia abdominală a evidenţiat o masă intraluminală rotund-ovalară, având semnal vascular prezent, situată în cadranul abdominal inferior stâng, cu dimensiuni de 20/15 mm. Colonoscopia a evidenţiat un polip pedunculat al colonului stâng pentru care s-a practicat electrorezecţie. Scopul acestei comunicări este de a atrage atenţia asupra importanţei hematocheziei la copii şi asupra necesităţii aderării la ghidurile actuale privind evaluarea endoscopică a tractului gastrointestinal la această vârstă.

Introduction

The intestinal polyp is defined as a tumoral mass protruding in the gastrointestinal lumen, with various histopathological patterns, either as neoplastic or non-neoplastic type, and epithelial or non-epithelial type(1).

In the pediatric population, the main type consists in single or sporadic epithelial polyps; as many as 84% to 97% of these are juvenile polyps, with a peak age incidence of 2 to 6 years old, being more prevalent in boys than girls(2).

In terms of malignant transformation, the progression and recurrence of any type of non-neoplastic epithelial tumors is highly inexistent(3,4). Rarely, children develop neoplastic polyps, like an adenomatous one, classified as tubule-villous adenoma, tubular adenoma, and villous adenoma(5).

The standard procedure for the diagnosis and management of pediatric colorectal polyps is full colonoscopy(6). Nowadays, modern sonography empowered the detection rate of colonic polyps before performing colonoscopy, as a revolutionary screening tool, dependent of colonic preparation(7).

Case presentation

A previously healthy 5-year-old boy was refereed to our gastroenterology unit with a history of one month of intermittent rectal bleeding and mild abdominal pain. The pain was inconstant, located to the inferior left side of his abdomen. Rectal bleeding was described as bright red blood passing through rectum, with a normal stool, although initially there was a five-day history of diarrhea, vomiting and fever. Initially, he had a medical visit in a local unit and took medication for an infectious diarrhea, with intestinal antiseptics, antidiarrheal and probiotics, but the symptoms did not improve and in the past three weeks he had daily normal bowel movements, stools appearing as Bristol 4, covered by fresh appearing blood every after day (Figure 1), with no fever or any other acute illness, with no contact with unhealthy people, and no history of travel. Colonoscopy revealed a pedunculated polyp located 20 cm above the anal orifice.

There was no accompanying complains like vomiting, wight loss, dehydration or fever in the present. This was the first bleeding event for the patient, and blood in stool gradually increased. In the meantime, he had normal food ingestion, no family history for coagulopathies, inflammatory bowel disease or polyps. The medical history was also negative for adenocarcinoma of the digestive tract or for any family medical records of breast tumor, brain tumor or ovarian tumor.

On admission day, vital signs showed normal blood pressure (101/60 mmHg), heart rate 88 beats per minute, respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute, and temperature 36.5°C. He weighed 16.4 kg. The clinical examination revealed a well-nourished and hydrated patient, with no particular skin signs. The abdomen was soft and nondistended, with no pain during superficial palpation and only a mild tenderness on deep palpation; the perirectal examination did not reveal any lesions or skin tags. A surgical examination with digital rectal exam did not show any palpable mass.

The biological investigation showed minor dropping in patient’s hemoglobin level (12.5 mg/dl) one month ago to 10.9 mg/dl on admission. White blood cell count was 9.4×106/µL and platelet count was 366×103/µL. The screening for electrolytes, renal and liver function tests were within normal ranges, as well as inflammatory signs (C reactive protein: 1.3 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 6 mm/h). Coagulopathies were infirmed since international normalized ratio and partial thromboplastin time were all normal (1.05 and 34.6 s, respectively). There was a positive determination of fecal calprotectin performed by parents in the ambulatory (1420 µg/g, normal: <50 µg/g), but other biochemical and stool cultures were negative.

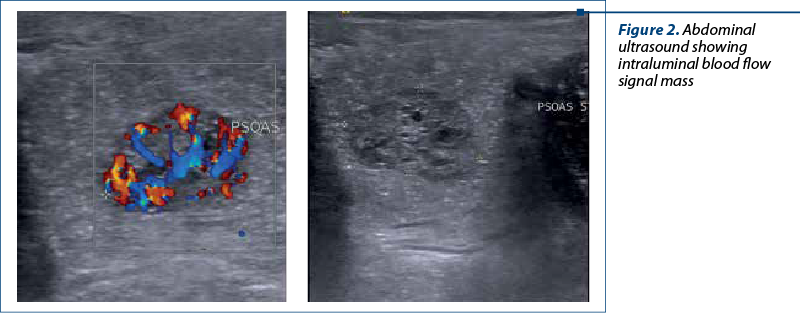

An abdominal ultrasound demonstrated no evidence of intussusception, but an abundant blood flow signal in a round pedunculated shaped intraluminal mass situated in the lower left abdomen area, measuring 20/15 mm (Figure 2).

Taking into account the possibility of a colonic juvenile polyp, the decision for colonoscopy was presented to legal guardians and we performed endoscopic exploration of the lower digestive tract, using an an electronic video endoscope (type CF-Q165L, Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan), under deep sedation performed by the anesthesiologist. The colonoscopy revealed a pedunculated polyp located 20 cm above the anal orifice (Figure 3). This solitary mass was covered by a smooth, bright red and friable epithelium.

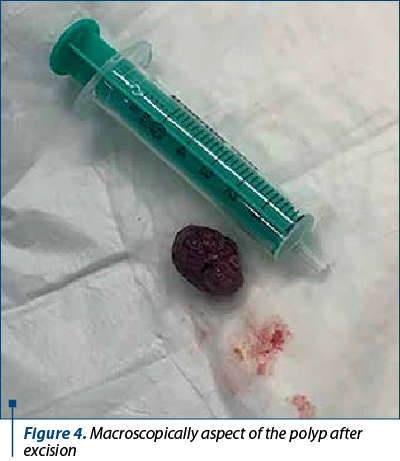

Saline solution was used to lift the submucosal layer and the mass was removed using electroresection with polypectomy snare, with no bleeding signs of the underlaying mucosa. The entire exploration of the colon, including the terminal ileum in the last 10 cm, revealed a normal mucosa with no additional polyps. The recovered polyp was a 21/14/11 mm mass (Figure 4) addressed to the pathology service, resulting in a light microscopy examination as a typically aspect of juvenile polyp with large tubular and cystic lakes over a flattened epithelium.

The patient had a benign evolution, without remarkable gastrointestinal signs. There were no complications after polypectomy, and we discharged the patient one day later. The one-month follow-up visit revealed normal stool and the decrease level of fecal calprotectin to less than 50 µg/g.

Discussion

Juvenile polyps represent benign hamartomas, with an incidence according to age between 2 and 10 years old, and a peak considered at 3-4 years old. Usually, there are no more than one or two polyps in 80% of cases(8). The classical form of clinical presentation is rectal bleeding, with or without mucus, in a normal appearing stool, and no pain associated(9). Only in a minority of cases there is lower abdominal pain, indicating the implantation place and the traction of the colonic tract. The majority of juvenile polyps are pedunculated, and some of them are sessile; the patients may experience massive rectal bleeding due to autoamputation. Bright red blood exteriorized with stool passage occurs when fecal bolus mechanically traumatizes the polyp during bowel movement. Depending on its location in the colonic segments, the blood tends to be darker and located in the middle of the evacuated stool. Rectosigmoid is the elective place of polyps’ location, implicated in as much as 60-80% of cases; thus, rectal examination reveals the luminal mass and sometimes there is a prolapsed tissue outside the anus in low rectal polyps(8,10).

Histologically, in children and adolescents, juvenile polyps (hamartomas) represent up to 85% of all cases, less than 10 % are adenomas, and only 3 % are hyperplastic(11). When an adenomatous polyp occurs during histology examination, mainly in older children and adolescents, one should take into account the actual guidelines for evaluation, management and follow-up, as part of a careful evaluation of polyposis syndrome(12,13).

The best way to evaluate colonic polyp in children is colonoscopy under deep sedation that enables in the meantime the safe removal and subsequently the microscopic analysis(14). Recurrent colonic polyps are regarded as rare in children, only 17% of single polyps having a relapse in the following years(15). Only patients having more than three juvenile polyps and a positive family history of colonic polyposis should be evaluated every two or three years in terms of colorectal cancer; even though the polyp itself is not malignant, the syndrome is associated with a higher incidence of colorectal neoplasia(12). The use of colonoscopy in young children takes into account the risk of sedation side effects and the particular narrow size of the colonic lumen that makes a great burden for the endoscopist. Previous experience showed that predicting the polyp’s location before colonoscopy helps the success of the procedure. This is why abdominal ultrasonography has been attributing an important role as a primary screening test for predicting the polyps’ location in the intestinal tract, being both safe and accurate(7). Most of the false-negative ultrasonographic results are explained by small polyp size, examinator experience and training, and by the rectal localization of the polyps. The rate of detection is increased if the exam is performed after colonic enema preparation, with an ultrasonographic diagnosis in up to 97% cases; our patient underwent abdominal ultrasonography after the initiation of the bowel preparation for colonoscopy and the polyp was successfully detected prior to colonoscopy.

Fecal calprotectin (FC) is a protein located in the cytoplasm of neutrophils, additionally distributed in the cytoplasm of monocytes, macrophages and granulocytes, known for its antimicrobial role(16,17). The most important clinical role is in the screening and management of inflammatory bowel diseases patients, who release calprotectin in the gastrointestinal tract due to leukocyte recruitment and to activation in the process of inflammation located in the bowel mucosa through proinflammatory chemokines(18). As a consequence, the destructions of implicated cells release calprotectin extracted to feces and thus measurable, in various conditions, such as infectious diarrhea, eosinophilic colitis, colorectal malignancies and drugs enteropathies(19,20). Recent studies have revealed high levels of fecal calprotectin in patients with intestinal polyps, considered as a part of the highly inflammatory process within the polyp cells. FC levels are less high than in inflammatory bowel disease patients, as shown in the Olafsdottir et al. study(21), but the exact value is related to the size and number of polyps(22). We can benefit today of noninvasive screening tools like fecal calprotectin and well-trained ultrasonography(23).

Conclusions

The aim of this report was to draw the attention to the importance of hematochezia in children and to the need for adherence to actual guidelines regarding the endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract in children.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Kleinman E, Goulet OJ, Giorgina MV, Sanderson IR, Sherman P, Shneider BL. Walker’s Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disease, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, 6th edition, 2018.

-

Waitayakul S, Singhavejsakul J, Ukarapol N. Clinical Characteristics of colorectal polyp in Thai children: a retrospective study. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2004 Jan;87(1):41-6.

-

Hood B, Bigler S, Bishop P, Liu H, Ahmad N, Renault M, Nowicki M. Juvenile polyps and juvenile polyp syndromes in children: a clinical and endoscopic survey. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011 Oct;50(10):910-5.

-

Heiss KF, Schaffner D, Ricketts RR, Winn K. Malignant risk in juvenile polyposis coli: increasing documentation in the pediatric age group. J Pediatr Surg. 1993 Sep;28(9):1188-93.

-

Tam YH, Lee KH, Chan KW, Sihoe JD, Cheung ST, Mou JW. Colonoscopy in Hong Kong Chinese children. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar 7;16(9):1119-22.

-

Baek MD, Jackson CS, Lunn J, et al. Endocuff assisted colonoscopy significantly increases sessile serrated adenoma detection in veterans. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:636–42;

-

Qu NN, Liu RH, Shi L, Cao XL, Yang YJ, Li J. Sonographic diagnosis of colorectal polyps in children: Diagnostic accuracy and multi-factor combination evaluation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(39):e12562.

-

Lee BG, Shin SH, Lee YA, Wi JH, Lee YJ, Park JH. Juvenile polyp and colonoscopic polypectomy in childhood. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2012;15(4):250-255.

-

Campbell AM, Sugarman I. Does painless rectal bleeding equate to a colonic polyp? Arch Dis Child. 2017 Nov;102(11):1049-1051.

-

Balkan E, Kiriştioğlu I, Gürpinar A, et al. Sigmoidoscopy in minor lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78(3):267-8.

-

Thakkar K, Alsarraj A, Fong E, et al. Prevalence of colorectal polyps in pediatric colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2012 Apr;57(4):1050-5.

-

Kay M, Eng K, Wyllie R. Colonic polyps and polyposis syndromes in pediatric patients. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015 Oct;27(5):634-41.

-

Kay M, Wyllie R. Pediatric Colonoscopic Polypectomy Technique. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020 Mar;70(3):280-284.

-

Latt TT, Nicholl R, Domizio P, et al. Rectal bleeding and polyps. Arch Dis Child. 1993 Jul;69(1):144-7.

-

Fox VL, Perros S, Jiang H, Goldsmith JD. Juvenile polyps: recurrence in patients with multiple and solitary polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Sep;8(9):795-9.

-

Roca M, Rodriguez Varela A, Carvajal E, Donat E, Cano F, Armisen A, et al. Fecal calprotectin in healthy children aged 4-16 years. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 25;10(1):20565.

-

Rugtveit J, Brandtzaeg P, Halstensen TS, Fausa O, Scott H. Increased macrophage subset in inflammatory bowel disease: apparent recruitment from peripheral blood monocytes. Gut. 1994;35(5):669–74.

-

Nisapakultorn K, Ross KF, Herzberg MC. Calprotectin expression inhibits bacterial binding to mucosal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69(6):3692–6.

-

Voganatsi A, Panyutich A, Miyasaki KT, Murthy RK. Mechanism of extracellular release of human neutrophil calprotectin complex. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70(1):130–4;

-

Chen CC, Huang JL, Chang CJ, Kong MS. Fecal calprotectin as a correlative marker in clinical severity of infectious diarrhea and usefulness in evaluating bacterial or viral pathogens in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(5):541–7.

-

Olafsdottir I, Nemeth A, Lorinc E, Toth E, Agardh D. Value of fecal calprotectin as a biomarker for juvenile polyps in children investigated with colonoscopy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(1):43–6.

-

Khan F, Mani H, Chao C, Hourigan S. Fecal calprotectin as a future screening tool for large juvenile polyps. Glob Pediatr Health. 2015;2:2333794X15623716.

-

Di Nardo G, Esposito F, Ziparo C, et al. Faecal calprotectin and ultrasonography as non-invasive screening tools for detecting colorectal polyps in children with sporadic rectal bleeding: a prospective study. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46:66.