Purpura fulminans, modalitate de debut clinic în sindromul inflamator multisistemic la copil (MIS-C)

Purpura fulminans, presenting feature of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

Abstract

Introduction. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been a worldwide health issue since early 2020, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Even though children do not usually present with severe COVID-19 unless the patient has an underlying disease, postinfectious complications, such as the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), have been a significant cause of child morbidity and mortality during the pandemic. Even more challenging is that MIS-C has a very broad differential diagnosis due to its clinical heterogeneity. Case report. We report the case of a 6-month-old infant without another medical history who was brought to the general practitioner’s office for persistent fever and cough. The symptoms did not ameliorate under antipyretic and mucolytic treatment, so the patient later presented in the emergency room with associated dyspnea, diarrhea, vomiting and rapidly generalizing purpuric skin lesions suggestive of purpura fulminans. He was admitted into our hospital and received empirical antibiotic treatment. He also developed neck stiffness. Meningococcemia was thus suspected; however, all cultures came out negative. Laboratory studies showed an important inflammatory syndrome, thrombocytopenia, severe anemia, coagulopathy, low protein C, protein S and antithrombin levels, low fibrinogen, high D-dimer levels and hypoalbuminemia. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no evidence of brain lesions. SARS-CoV-2 IgG-type antibodies were positive, therefore MIS-C was suspected. The laboratory studies were extended and revealed high NT-proBNP, IL-6 and IL-2 soluble antigen levels. Other possible diagnoses were excluded, which permitted our team to establish the diagnosis of MIS-C. The specific treatment was initiated with intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) and high-dose methylprednisolone associated with enoxaparin, broad-spectrum antibiotics and with symptomatic treatment. The patient rapidly evolved well, with the remission of fever, inflammatory syndrome, coagulopathy and all other clinical and laboratory alterations. The skin lesions ameliorated as well, however, at a slower pace. Conclusions. MIS-C is a potentially life-threatening complication of COVID-19 in children. Therefore, clinicians must maintain a high degree of suspicion in the setting of the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, the diagnostic criteria should be strictly followed due to the clinical similarities this pathology might have with other known diseases.Keywords

purpura fulminanssevere acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2multisystem inflammatory syndrome in childrenthrombosisRezumat

Introducere. Încă de la începutul anului 2020, boala coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) a reprezentat o mare problemă de sănătate pe întreg globul, mai ales la adulţii cu comorbidităţi, fiind cauzată de coronavirusul sindromului respirator acut sever 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Spre deosebire de adulţi, în rândul copiilor COVID-19 adesea a determinat forme uşoare de boală sau a fost asimptomatic. Sindromul inflamator multisistemic la copii (MIS-C) este o complicaţie postinfecţioasă extrem de severă, fiind o cauză importantă de morbiditate şi mortalitate care nu de puţine ori necesită proceduri invazive sau internare în secţiile de terapie intensivă. Prezentare de caz. Prezentăm cazul unui sugar în vârstă de 6 luni, fără antecedente personale patologice semnificative, care a prezentat purpura fuminans în contextul MIS-C. Manifestările de debut au fost reprezentate de ascensiuni febrile şi accese de tuse seacă. Iniţial a primit tratament la domiciliu cu antipiretice şi mucolitice, dar evoluţia a fost nefavorabilă, asociind dispnee, diaree şi vărsături alimentare, alături de persistenţa febrei înalte (până la 40°C), necesitând internare. În decurs de câteva ore de la internare, pacientul a prezentat numeroase leziuni cutanate purpurice, rapid generalizate, fiind înalt sugestive pentru meningococemie. Cu toate acestea, ecografia transfontanelară şi imagistica prin rezonanţă magnetică (IRM) la nivel cerebral nu au decelat leziuni cerebrale, iar cultura din lichidul cefalorahidian (LCR) şi hemoculturile au infirmat o infecţie bacteriană. Investigaţiile de laborator au decelat un sindrom inflamator important (fără a se decela o etiologie bacteriană sau virală), trombocitopenie şi anemie severă cu necesar transfuzional. Inflamaţia multisistemică severă a fost confirmată de nivelul seric de IL-6 şi de prezenţa coagulopatiei intravasculare diseminate. De asemenea, evaluarea cardiacă a confirmat suferinţa miocardului, cu hipertrofie vetriculară bilaterală şi cu un nivel seric mult crescut al NT-pro-BNP. În absenţa altor cauze care să explice manifestările clinice şi parametrii de laborator şi ţinând cont de contextul epidemiologic, s-a luat în considerare MIS-C, diagnostic confirmat de anticorpii de tip IgG SARS-CoV-2 pozitivi în titru mare. S-a iniţiat tratament cu imunoglobuline intravenoase, corticoterapie (metilprednisolon) şi antibioterapie cu spectru larg, conform recomandărilor internaţionale. Evoluţia a fost favorabilă, cu remisiunea ascensiunilor febrile şi a manifestărilor clinice, cu vindecarea leziunilor cutanate şi negativarea sindromului inflamator. Concluzii. Sindromul inflamator multisistemic la copii este o complicaţie extrem de severă a COVID-19 şi are un tablou clinic foarte polimorf, manifestările cutanate fiind adeseori întâlnite. De la erupţii banale care mimează urticaria până la leziuni cutanate severe cu purpură şi necroze, toate acestea trebuie să îi menţină medicului pediatru un grad ridicat de suspiciune, mai ales în contextul infecţiei cu SARS-CoV-2.Cuvinte Cheie

purpura fulminanscoronavirusul sindromului respirator acut sever 2sindrom inflamator multisistemic la copiitrombozăIntroduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been a worldwide health issue since early 2020, its emergence dating in late 2019 in Eastern China. It is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Its high level of contagiousness, the rapid spread and the tendency to severely affect the elderly and the young, overwhelming the healthcare systems, have led the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare the outbreak a pandemic in March 2020(1,2). However, it is a well-known fact that infected children mainly develop inapparent or mild forms, affecting the upper airways rather than the lower airways, if there is no underlying pathology associated, such as obesity, asthma or congenital cardiac malformations. The mechanism through which children are spared from severe manifestations of COVID-19 is still under debate. Still, the most plausible theory is that protection in the pediatric population is conferred by the lower levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). The explanation is that SARS-CoV-2 uses ACE2 as a receptor to cross the cellular membranes of the alveoli and other sites. Therefore, a lower level of ACE2 leads to fewer intracellular viral copies and, thus, to a milder inflammatory response, causing less damage(3).

Even though children are less affected by the acute infectious disease, the possible postinfectious complications can be devastating, the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) being one of them. MIS-C includes a heterogenous group of clinical and paraclinical manifestations resembling other known diseases, such as Kawasaki disease (KD), toxic shock syndrome (TSS) or macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)(1,4).

Out of all clinical manifestations that MIS-C presents, mucocutaneous involvement is one of the most frequent and variable in aspect, present in approximately 75% of cases. Several eruptions have been associated with MIS-C, including a nonspecific maculopapular rash, chilblain-like lesions, livedo reticularis or petechiae(5). Intrainfectious skin eruptions are also possible and variable with COVID-19. Besides the more frequent and benign lesions previously described as being associated with MIS-C, which can also accompany COVID-19, the literature has noted several cases of a life-threatening cutaneous manifestation, namely purpura fulminans(6-8). However, just one case of purpura fulminans in a MIS-C patient has been reported to the present time, to our knowledge(9).

Hence, correctly establishing the diagnosis of MIS-C can be a real challenge, especially in the setting of such a broad differential diagnosis. WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have proposed numerous diagnostic criteria(4).

Case presentation

We report the case of a 6-month-old infant who had no previous medical history and originated from a low-income environment. He was fully vaccinated following the National Health Ministry recommendations. Namely, he received two shots of pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccines but no meningococcal shot, as it is not mandatory in our country. He was first evaluated by the general practitioner for persistent high-grade fever and cough that had been present for approximately one week. Antipyretic and mucolytic medication was prescribed, and the patient was treated at home. However, the evolution was not good, as the symptoms persisted and were subsequently associated with dyspnea, watery, mucous stools and vomiting. On admission to a territorial hospital, he was severely dehydrated and cyanotic, with a blood pressure of 95/53 mmHg, presenting intercostal retractions, bilateral crackles and an oxygen saturation of 85% under supplemental oxygen. The laboratory studies showed elevated inflammatory markers and metabolic acidosis, while the chest X-ray revealed multiple bilateral ground-glass lung opacities. He soon developed skin purpura that generalized within 30 minutes, suggestive of purpura fulminans.

In the setting of the patient’s acute respiratory failure and the rapidly progressive eruption, he was transferred to the intensive care unit of our hospital. The skin lesions continuously extended, some evolving into hemorrhagic phlyctenae and skin necrosis (Figure 1); moreover, the patient developed neck stiffness and deglutition difficulties. A more detailed laboratory evaluation was conducted, and it revealed a significant inflammatory syndrome (C-reactive protein [CRP] value of 11.41 mg/dl, procalcitonin 90.11 ng/ml), thrombocytopenia (62,000/mm3), hypochromic, and microcytic anemia (6.3 g/dl). He presented coagulopathy (INR 2.18; APTT 67.2 s), low fibrinogen levels (68 mg/dl), elevated D-dimer level (6.800 ng/ml) and low values of antithrombin, protein C and protein S activities, all these suggestive for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Meningococcemia was suspected, but the culture from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood culture were negative, so this diagnosis was not confirmed.

Moreover, both the transfontanellar ultrasound and the cerebral MRI were normal. Other sites of infections have been excluded by the normal chest X-ray and negative stool and urine cultures. SARS-CoV-2 real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus serology were all negative. The infant developed generalized edema secondary to hypoalbuminemia, with kidney function markers within normal ranges. We extended the investigations, and we identified high lactate dehydrogenase (850 U/l), elevated lactate levels (9.4 mmol/l) and NT-proBNP levels (17.743 pg/ml). All these clinical findings and the inflammatory syndrome, the laboratory parameters and the epidemiological context were suggestive of MIS-C. Therefore, the family’s COVID-19 status was evaluated; the patient’s parents were unvaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 and were unaware of any recent contact with infected people. SARS-CoV-2 IgG-type antibodies were positive in our patient, while IgM-type antibodies were negative. Other inflammatory markers were measured, revealing a high level of both interleukin 6 (218.88 pg/ml) and interleukin 2 (1241 kU/L). Echocardiogram revealed biventricular hypertrophy, normal systolic function, and small pericardial effusion, but without coronary artery aneurysms.

The patient was diagnosed with MIS-C, and guideline-recommended treatment was initiated. Our patient received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG; 2 g/kg), and dexamethasone was replaced with intravenous methylprednisolone (2 mg/kg/day). Anticoagulant therapy was started, initially in prophylactic doses, later in therapeutic doses, after correcting the thrombocyte count (enoxaparin, 1 mg/kg/dose, two doses daily). Oxygen supplementation was necessary, and he received antibiotic treatment (ceftriaxone associated with vancomycin), intravenous albumin infusion, fresh frozen plasma for coagulopathy and erythrocyte transfusion due to severe anemia. Shortly after this treatment started, the fever remitted, the neurological status improved significantly, and the purpuric lesions began to heal. The laboratory studies showed the normalization of all parameters, including CRP, procalcitonin, D-dimer, INR, APTT, anticoagulant factors’ activities, NT-proBNP and IL-6. We began the oral administration and taper of methylprednisolone doses after approximately 10 days, without recurrences. Antibiotic therapy was discontinued after 14 days. He was discharged after a 28-day hospitalization.

Discussion

COVID-19 has been a worldwide public health issue since early 2020. This fact resides in the high contagiousness, and the overwhelming hospitalization rates and mortality of SARS-CoV-2. However, this has applied to adults only; thus, the pediatric population was somehow out of sight. While studies report an overall hospitalization rate of approximatively 7% in adults, rising to 9.2% in the over 60 years-old patients, the epidemiology of pediatric COVID-19 shows a lower hospitalization rate of just about 1%(10,11). The pediatric COVID-19 mortality rates have been low as well, at 0.04%(12). Even though MIS-C is a relatively rare complication of COVID-19, its consequences are worthy of consideration. One Canadian study has documented that nearly all MIS-C cases required hospitalization (namely, 99%), and that approximately one-third of the patients were admitted into the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU)(13). Furthermore, a systematic review has observed that 1.7% of MIS-C cases resulted in death. Compared to COVID-19, MIS-C mortality rates are about 40 times higher(14).

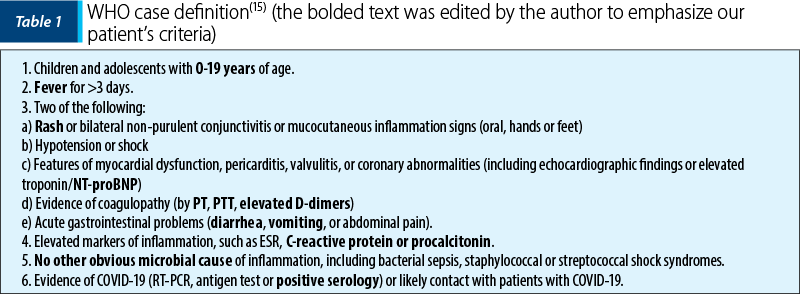

WHO case definition of MIS-C is presented in Table 1 – all six criteria are needed to establish the diagnosis(15). Our patient was eligible for MIS-C diagnosis, according to the WHO criteria, especially in the presence of serological proof of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. However, recent literature has not clearly stated the exact spectrum of skin eruptions typically seen in MIS-C. In the list of diagnostic criteria, “rash” is included with no further detail, which can be both helpful and confusing when tackling a potential case. Moreover, when the cutaneous manifestations are typical for other medical entities, one must judiciously apply the diagnostic criteria given the broad differential diagnosis of MIS-C.

In a patient with high fever, neurological signs and rapidly generalizing purpura, the main suspicion is that of purpura fulminans, typically and most frequently associated with meningococcemia(16,17). Due to the high mortality rate of meningococcal disease and the risk of rapid shock development, our patient was promptly administered empirical antibiotics after culture sampling. Even though more recent studies report a decrease in death rates, they remain significantly high. Specifically, the mortality of PICU-admitted patients with meningococcemia was 9% in a retrospective study(18). However, positive cultures are needed for a positive diagnosis; in our patient, all cultures were negative, which led our medical team to search for an alternate diagnosis.

MIS-C can affect almost all organs, from the cutaneous and mucosal manifestations, lymphadenopathy, and ocular involvement to the organ-specific manifestations (gastrointestinal, hepatic, neurologic, cardiac, renal, respiratory and hematological)(19-21). Medical studies have shown that MIS-C skin manifestations have been highly polymorphic, ranging from minimal diffuse rash, red hands and feet, maculopapular eruptions like measles, urticarial lesions, and livedo reticularis, papulovesicular lesions to necrotizing lesions. Dermal microcirculation thrombosis is known to be the process responsible for the development of purpura fulminans, which may be the explanation for the unusual cutaneous manifestation presented by our patient(17). Our child presented purpura fulminans associated with MIS-C, with severe skin lesions and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) due to hyperinflammatory states. It has been demonstrated that MIS-C induces hypercoagulability, with antithrombin III, protein C and protein S consumption which triggers microthrombi formation, microangiopathy, massive thrombocyte, coagulation factors consumption and, finally, a high hemorrhagic risk, a mechanism which is similar to that of DIC(19-21). Considering the variability of cutaneous eruption in MIS-C, any skin lesion associated with fever and the absence of other infectious causes, the physician must consider SARS-CoV-2 infection and proceed with investigations in this regard.

Conclusions

MIS-C is a potentially life-threatening complication of COVID-19 in children. Therefore, clinicians must maintain a high degree of suspicion in the setting of the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Moreover, the clinical presentation can be confusing due to similarities to other known pathologies and heterogeneous manifestations. Children must be rapidly diagnosed so that specific treatment can be initiated. However, other more plausible differential diagnoses must be excluded to avoid overdiagnosing MIS-C and unnecessarily exposing children with serious infectious diseases, such as bacterial sepsis or meningococcemia, to high doses of corticoids.

Acknowledgment: This research was funded by the “Iuliu Haţieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, Grant number 35160/17.12.2021.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Son MBF, Friedman K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) clinical features, evaluation and diagnosis. UpToDate; 2021 [updated 2021 April 02; cited 2022 February 02]. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-mis-c-clinical-features-evaluation-and-diagnosis

-

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157-160.

-

Borrelli M, Corcione A, Castellano F, Fiori Nastro F, Santamaria F. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children. Front Pediatr. 2021; 9:668484.

-

Esposito S, Principi N. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Related to SARS-CoV-2. Paediatr Drugs. 2021:1-11.

-

Naka F, Melnick L, Gorelik M, Morel KD. A dermatologic perspective on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39(1):163-168.

-

Khan IA, Karmakar S, Chakraborty U, Sil A, Chandra A. Purpura fulminans as the presenting manifestation of COVID-19. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1149):473.

-

Sanaei Dashti A, Dehghani SS, Moravej H, Abootalebi SN. Association of COVID-19 Infection and Purpura Fulminans. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. 2021;9(4):e109843.

-

Pavlovich Zhitny V, Lyons M, Perloff A, Menezes J, Pistorio A, Baynosa R. COVID-19 association with purpura fulminans: report of a life-threatening complication in a fully vaccinated patient. J Surg Case Rep. 2022;2022(3):1-3.

-

Parappil P, Ghimire S, Saxena A, Mukherjee S, John BM, Sondhi V, et al. New-onset diabetic ketoacidosis with purpura fulminans in a child with COVID-19-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022;54(7):522-528.

-

Mahajan S, Caraballo C, Li SX, Dong Y, Chen L, Huston SK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Hospitalization Rate and Infection Fatality Rate Among the Non-Congregate Population in Connecticut. Am J Med. 2021;134(6):812-816.e2.

-

American Academy of Pediatrics. Children and COVID-19: State Data Report. A joint report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association Summary of publicly reported data from 49 states. 2022 Mar 31. Summary of State-Level Data Provided in this Report. page 4.

-

Kim TY, Kim EC, Agudelo AZ, Friedman L. COVID-19 hospitalization rate in children across a private hospital network in the United States: COVID-19 hospitalization rate in children. Arch Pediatr. 2021;28(7):530-532.

-

Laverty M, Salvadori MI, Squires SG, Ahmed MA, Eisenbeis L, Lee SJ, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in Canada. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2021;47(11):461–5.

-

Kaushik A, Gupta S, Sood M, Sharma S, Verma S. A Systematic Review of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(11):e340-e346.

-

World Health Organization. (2020). Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents with COVID-19: scientific brief, 15 May 2020. World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332095. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

-

Siddiqui JA, Ameer MA, Gulick PG. Meningococcemia. [Updated 2021 Dec 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534849/

-

Veldman A, Fischer D, Wong FY, et al. Human protein C concentrate in the treatment of purpura fulminans: a retrospective analysis of safety and outcome in 94 pediatric patients. Crit Care. 2010;14:R156.

-

Thorburn K, Baines P, Thomson A, Hart CA. Mortality in severe meningococcal disease. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:382-385.

-

Farooq A, Alam F, Saeed A, Butt F, Khaliq MA, Malik A, et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Adolescents (MIS-C) under the Setting of COVID-19: A Review of Clinical Presentation, Workup and Management. Infect Dis (Auckl). 2021 Jun 20;14:11786337211026642. doi: 10.1177/11786337211026642.

-

Esmon CT. The interactions between inflammation and coagulation. BJ Haem. 2005 Oct 21; 131(4):417-30.

-

Konda S, Zell D, Milikowski C, Alonso-Llamazares J. Purpura Fulminans Associated with Streptococcus pneumoniae Septicemia in an Asplenic Pediatric Patient. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104(7):623-7.