Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNBO) is an autoinflammatory bone disease with a low incidence in association with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). The autoimmune mechanisms are suspected in the pathogenesis of the disease, and whenever it complicates JIA, it changes the initial arthritis therapeutic approach. The authors present the case of a boy with JIA, enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) subtype, complicated with recurrent right clavicle CNBO, along with the clinical evolution and the treatment strategies.

Rare associations in juvenile idiopathic arthritis – chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis

Asocieri rare în artrita juvenilă idiopatică – osteomielita cronică nonbacteriană

First published: 30 aprilie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Pedi.69.1.2023.7985

Abstract

Rezumat

Osteomielita cronică nonbacteriană (CNBO) este o boală osoasă autoinflamatorie cu incidenţă scăzută în asociere cu artrita idiopatică juvenilă (AIJ). Mecanismele autoimune sunt suspectate în patogeneza bolii şi, ori de câte ori CNBO complică AJI, se modifică şi abordarea terapeutică iniţială a artritei. Autorii prezintă cazul unui băiat cu AJI, subtipul ERA (artrită asociată entezitei), complicată cu CNBO recurentă la clavicula dreaptă, împreună cu evoluţia clinică şi strategiile de tratament.

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common rheumatic disease of children, and it can start as young as infancy. Its evolution is unpredictable, even when the disease appears to be therapeutically controlled, being influenced by numerous factors, most commonly undiagnosed and untreated comorbidities. As a consequence, complications may occur which induce relapse or even partial response to the underlying treatment. Compared to other rheumatic diseases, JIA has a much higher risk of one comorbidity (18.7%) versus systemic lupus (11.1%), or for more than two comorbidities (1.5% for JIA versus 0.3% for systemic lupus). The biggest pitfalls are the associated diseases that have a low incidence but a nonspecific or even sometimes superimposable clinical picture to that of JIA, and can be misinterpreted at least in the initial phase as relapsing arthritis.

Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNBO) associated with JIA may induce delay in its diagnosis and treatment, by the similarity of clinical expression associated with persistent inflammatory syndrome. CNBO belongs to the genetically transmitted autoinflammatory syndromes in which the molecular defect in monocytes induces a deficit of IL-10 synthesis and function, with consequences on the compensatory stimulation of some proinflammatory cytokines. This induces persistence of inflammation and bone matrix damage by activating osteoclast differentiation and activity.

On the other hand, antibiotic therapy frequently initiated in the first phase not only does not induce remission, but also delays the early positive diagnosis.

The authors present the challenges of diagnosis and therapeutic management in a child diagnosed with JIA subtype ERA and who, during the disease development, associated chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis.

Clinical case

The patient B.E.A., 9 years old, male, from rural area, came to the Second Pediatrics Clinic in Iaşi on 25.09.2022 for control. From the history of this patient, we noticed several significant moments.

First admission – November 2020

The clinical exam showed intermittent arthralgias for more than six months in different locations: bilateral at the knee level, tibiotarsal, metatarsophalangeal right leg, left sacroiliac, dorsolumbar, genu valgum, talus valgus, mild locomotor functional deficit (limp gait), no fever; H=143 cm, W=40.5 kg, BMI= 19.85 kg/m2.

The biological picture showed the presence of an inflammatory syndrome (ESR x 2.75 ULN, CRP x 2 ULN, ferritin with increased values); there was also found a calcium deficiency. The following investigations had values within normal limits or tested negative: liver and kidney function tests, total proteins and electrophoresis, anti-Epstein-Barr IgG and IgM antibodies, anti-Borrelia burgdorferi IgM, IgA and IgG antibodies, PPD intradermoreaction, CPK, LDH, rheumatological antibodies panel, rheumatoid factor, alpha-fetoprotein, pharyngeal and nasal swab cultures, urinalysis, stool occult hemorrhages, fecal calprotectin, RT-PCR COVID-19. HLA B27 Ag was positive. The ophthalmologic exam for the anterior pole was normal and anti-CCP antibodies were absent.

Prior to admission, there were also performed lumbosacral spine X-ray, pelvic X-ray and bilateral tibiotarsal X-ray which were correlated with orthopedic examination, establishing the diagnosis of bilateral lumbar disc sciatica and bilateral ankle valgus, without the need for any orthopedic treatment at that time.

The established diagnosis at that time was seronegative juvenile idiopathic arthritis – ERA subtype (HLA B27 positive), mild locomotor functional deficit and hypocalcemia. He was treated with pulses of methylprednisolone, then continued with chronic disease-modifying antirheumatoid drug (DMARD) – sulfasalazine.

Second admission – December 2020

The patient presented for arthralgias at both knees and at the right bilateral tibiotarsal level accompanied by local cracks and dorsolumbar arthralgias. Biologically, the inflammatory syndrome increased (ESR x 2.6 ULN, PCR x 2 ULN, ferritin x 1.2 VN), IgG with increased values and calcium deficiency. The treatment with sulfasalazine was continued, to which oral methotrexate was added.

Third admission – February 2021

The reason for admission was the appearance three weeks before of a small pseudotumor at the right clavicle, with inflammatory characteristics, showing spontaneous and palpatory pain. The biological picture maintained the inflammatory syndrome (ESR x 2.1 ULN, ferritin x 1.4 ULN). The orthopedic exam was performed and the diagnosis was right sternoclavicular disjunction, followed by immobilization of right upper thoracic limb with elastic bandages for four weeks. He continued the previous treatment with two DMARDs – sulfasalazine and methotrexate.

The clinical evolution was favorable – at one month, he maintained discrete right clavicular swelling, but without tenderness or local inflammatory signs. Sulfasalazine was stopped in May 2021.

November 2021

The patient presented for enlargement of the inner extremity of the right clavicle with pseudotumoral appearance, dimensions 4/4 cm, accompanied by significant local pain, especially at night and on palpation; the other joints showed intermittent bilateral knee arthralgia without clinically suggestive elements of active arthritis.

The biological parameters revealed again a significant inflammatory syndrome (ESR x 5.5 ULN, PCR x 6 ULN). Liver and kidney function tests, rheumatoid factor, anti-dsDNA antibodies, alpha-fetoprotein, immunogram, coagulogram, total proteins and electrophoresis, phospho-calcic metabolism, pharyngeal and nasal swab cultures, urinalysis, RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 – they were all negative or with values within normal limits.

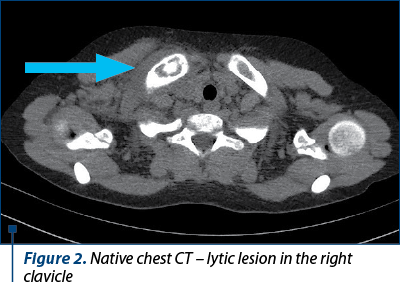

Native chest CT showed a normal appearance except for a lytic lesion on the right clavicle, at the inner extremity (Figure 2).

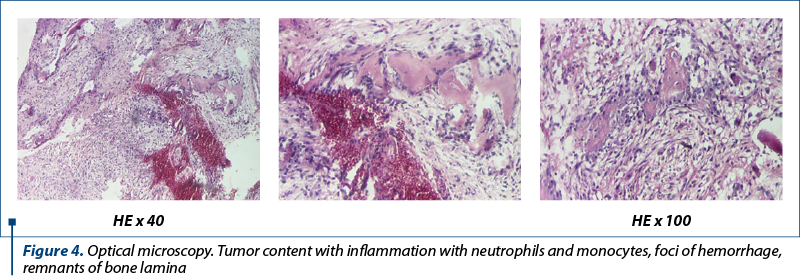

A biopsy was performed and the pathology specimens revealed tumor content with bone sequestration, thrombosis, remnants of bone laminae, establishing the diagnosis of right clavicle subacute osteomyelitis (Figures 3 and 4). The cultures were negative.

The patient was put on antibiotic treatment – clindamycin for three weeks, combined with methotrexate, with a slightly favorable evolution.

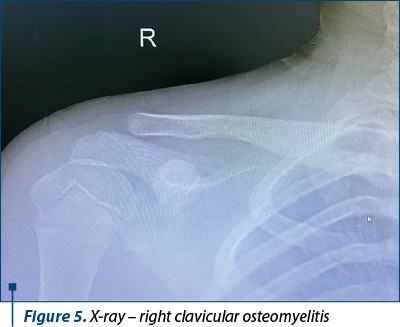

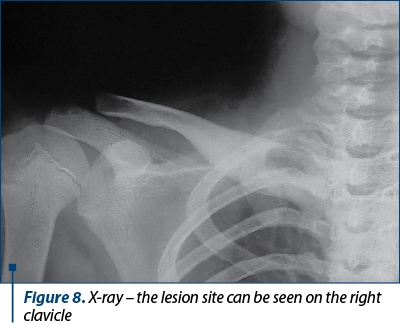

In March 2022, the patient presented for control in the Pediatric Orthopedics Department. Clinically, he had no fever, but there were edema and significant pain in the right clavicle – inner extremity, otherwise no other pathological changes. The inflammatory syndrome was present (ESR x 4.83 ULN, PCR x 5 ULN). The diagnosis was subacute osteomyelitis in the right clavicle – second relapse, seronegative JIA subtype ERA HLA B27 positive, bilateral valgus feet and genu valgum. A second clindamycin administration for three weeks along with methotrexate continuation led to a clinical and biological improvement of the inflammatory syndrome. The lesion could be seen on chest X-ray.

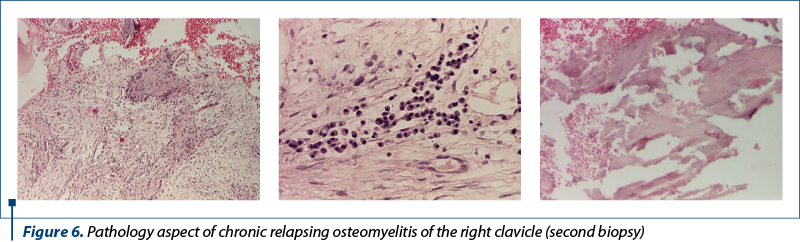

In June 2022, at the following admission in the Pediatric Orthopedics Department, a spontaneous and palpatory exacerbation of pain at the osteomyelic lesional site of the right clavicle was found. The biological picture revealed significant inflammatory syndrome (ESR x 5.7 ULN, PCR x 7 ULN); hepatorenal samples, AFP and coagulogram were within normal limits. The second biopsy also showed tumor content – sequestration, fibrosis, necrosis, hemorrhage and chronic lymphoplasmocytic inflammation (Figure 6). Cultures from the lesion were also negative.

The diagnosis at that moment was chronic nonbacterial recurrent osteomyelitis of the right clavicle – third relapse, seronegative JIA subtype ERA – HLA B27 positive, bilateral valgus feet and genu valgum. The treatment option taken were pulses of methylprednisolone and continuation of

methotrexate.

In September 2022, the patient came for control. The clinical exam showed H=152 cm, W=50 kg, BMI=21.64 kg/m2, afebrile, postoperative scar at the right clavicle, the area being mildly tender at palpation, bilateral genu valgum, bilateral valgus foot, bilateral knee arthralgia, but no joint swelling or locomotor functional deficit (Figure 7).

The biological picture revealed minimal inflammatory syndrome (ESR x 1.75 ULN, PCR – normal values); hepatorenal samples, immunogram, phosphocalcic metabolism, alpha-fetoprotein, rheumatoid factor, total proteins and electrophoresis, lipidogram, urinalysis, stool bleeding – absent; pharyngeal and nasal exudates were negative.

The positive diagnosis in this complex case was thus formulated:

1. AJI seronegative subtype ERA HLA B27 positive.

2. Relapsing chronic single focal nonbacterial osteomyelitis of the right clavicle.

3. Bilateral valgus foot.

4. Bilateral genu valgum.

5. Overweight.

Although apparently having the improvement of joint manifestations in JIA ERA subtype, the association of chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis trigger with recurrent evolution may increase the rate of relapse into joint disease and the rapid onset of complications.

Discussion

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis may be associated with numerous comorbidities at onset or at any time during its course, including autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis, autoimmune hepatitis/thyroiditis, celiac disease, diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency, psoriasis and/or inflammatory bowel disease(1).

Their incidence ranges from very common to rare pathologies, raising numerous management challenges regarding the diagnosis and therapy of JIA. Their association not infrequently leads to recurrences of JIA or to the loss of therapeutic control.

Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNBO), an autoinflammatory bone disease, has a low incidence in association with JIA, but untreated leads to the worsening of JIA and to the development of therapy-resistant complications. CNBO is more common in childhood than in adults, with an incidence of 0.4/100,000 patients; however, the actual incidence seems to be higher because its symptoms are more nonspecific. Although it is classified as an autoinflammatory syndrome, 71% of children have a positive family history of autoimmunity. The bone involvement in the setting can be unifocal (20% of cases) or polyfocal (2-5 lesions in 50% of cases and more than five lesions in 27% of cases); in all clinical manifestations, there is bone pain with significant severity (VAS pain 8/10 – 20% of cases; VAS pain 9-10/10 – 23% of cases), fever (44.4% of cases), swelling of the affected area (27.8% of cases), or limb involvement (27.8%)(2).

Arthritis associated with CNBO has an incidence of 44.4% of cases, prioritizing spondyloarthropathy (25%). It seems that, due to polymorphic symptoms, there is a risk of delayed diagnosis, so that 75% of patients are diagnosed on average 11-18 months after the onset. Although 57% of cases are diagnosed by the rheumatologist in the first year of evolution, the first diagnosis in 30% of cases is of bacterial osteomyelitis, malignant tumors (30%), fracture (15%), arthritis (15%) and even growing pain (4%)(3-5). The evolving persistence of bone pain associated with local changes may suggest the diagnosis.

Most commonly affected are the lower limbs (50% of cases), spine (40% of cases), pelvis (38% of cases), clavicle (25% of cases), upper limbs (24% of cases), ribs and sternum (8% of cases), and even the mandible (18% of cases)(6).

Taking into account the polymorphism of clinical expression and its nonspecificity, the positive diagnosis will be one of exclusion of pathologies such as malignancies – bone tumors, hematological malignancies, metabolic diseases, bone infections, immunodeficiency syndrome, other autoinflammatory syndromes (IL1 receptor antagonist deficiency, PAPA syndrome, pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, MAJEED syndrome) to bone pathologies such as fibrous bone dysplasia or bone cyst(7-9).

Positive signs are evoked by imaging investigations, ranging from standard radiology (possibly suggestive in 12.5-37% of cases) to high-performance imaging investigations (CT/MRI which identifies possible bone destruction – 70% of cases, periosteal lesions and/or bone oedema – 11% of cases, changes in periosteal soft tissue – 35.3% of cases). Incidentally, the number of radiological lesions is used as a marker of disease activity according to the PedCNO score. Grids of scores based on imaging, clinical and laboratory changes are currently described to differentiate between infectious osteomyelitis CNBO and benign or malignant bone tumors in children. Often, especially in monofocal localization, although the imaging is suggestive of CNBO, the differential diagnosis requires bone biopsy(10-12).

The histopathological examination specifies the diagnosis, but it must be interpreted with caution in the clinical, biological and imaging context of the patient, especially in the first phase when it can objectify the appearance of acute inflammatory syndrome with neutrophils and may be confused with acute bacterial osteomyelitis, inducing a wrong antibiotic therapy(13). The long evolution is reflected histopathologically in particular by the appearance of fibrosis, necrosis, bone sequestration and especially chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. At this stage, the diagnostic clarification is much easier(14,15).

Consequently, at the first diagnosis, many patients risk receiving antibiotic therapy associated or not with NSAIDs, without stopping the disease progression, with the risk of triggering complications in the evolution of the disease.

The current therapeutic protocols for CNBO, with or without axial manifestation, propose as main therapy NSAIDs, and if remission is not achieved, the initiation of treatment with remitting drugs (methotrexate, sulfasalazine) and optional systemic corticotherapy. If the therapeutic control is not achieved, anti TNF-alpha biological agents (adalimumab, etanercept) and bisphosphonates (pamidronate) can be associated.

Apart from the problems created by the evolving pathological aspect of the disease, the psychological and socioeconomic impact on the patient is extremely important. Studies have shown that the patients experience impaired school performance (47-56%), absenteeism, fatigue (50%), sleep disorders (37%), anxiety (35%) or depression (32%), associated with a significant socioeconomic impact on the family (27-34%)(16).

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY

Bibliografie

- Natter MD, Ong MS, Mandl KD, Schanberg L, et al. Comorbidity Patterns in Children with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: The Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance Registry. 2014 ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting, abstract 1313.

- Schnabel A, Range U, Hahn G, Berner R, Hedrich CM. Treatment Response and Longterm Outcomes in Children with Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis.

- J Rheumatol. 2017;44(7):1058-1065. doi:10.3899/jrheum.161255.

- Kaiser D, Bolt I, Hofer M, et al. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis in children: a retrospective multicenter study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015;13:25. doi:10.1186/s12969-015-0023-y.

- Concha S, Hernández-Ojeda A, Contreras O, Mendez C, Talesnik E, Borzutzky A. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis in children: a multicenter case series. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(1):115-120. doi:10.1007/s00296-019-04400-x.

- Kaut S, Van den Wyngaert I, Christiaens D, et al. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis in children: a multicentre Belgian cohort of 30 children. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2022;20(1):41. doi:10.1186/s12969-022-00698-3.

- Silier CCG, Greschik J, Gesell S, Grote V, Jansson AF. Chronic non-bacterial osteitis from the patient perspective: a health services research through data collected from patient conferences. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017599. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017599.

- Hedrich CM, Hofmann SR, Pablik J, Morbach H, Girschick HJ. Autoinflammatory bone disorders with special focus on chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2013;11(1):47. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-11-47.

- Hofmann SR, Kapplusch F, Mäbert K, Hedrich CM. The molecular pathophysiology of chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis (CNO) – a systematic review. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2017;4(1):7. doi:10.1186/s40348-017-0073-y

- Hofmann SR, Kapplusch F, Girschick HJ, et al. Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO): Presentation, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2017;15(6):542-554. doi:10.1007/s11914-017-0405-9.

- Zhao Y, Ferguson PJ. Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis and Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis in Children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2018;65(4):783-800. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2018.04.003.

- Zhao DY, McCann L, Hahn G, Hedrich CM. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis (CNO) and chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4:100095. doi:10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100095.

- D’Angelo P, de Horatio LT, Toma P, et al. Chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis – clinical and magnetic resonance imaging features. Pediatr Radiol. 2021;51(2):282-288. doi:10.1007/s00247-020-04827-6.

- Jansson AF, Müller TH, Gliera L, et al. Clinical score for nonbacterial osteitis in children and adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(4):1152-1159. doi:10.1002/art.24402.

- Hedrich CM, Morbach H, Reiser C, Girschick HJ. New Insights into Adult and Paediatric Chronic Non-bacterial Osteomyelitis CNO. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22(9):52. doi:10.1007/s11926-020-00928-1.

- Kostik MM, Makhova MA, Maletin AS, et al. Cytokine profile in patients with chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Cytokine. 2021;143:155521. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155521.

- Oliver M, Lee TC, Halpern-Felsher B, et al. Disease burden and social impact of pediatric chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis from the patient and family perspective. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):78. doi:10.1186/s12969-018-0294-1.