Secondary biliary cirrhosis – a complication of choledochal cyst. Case report

Ciroză biliară secundară – complicaţie a chistului de coledoc. Prezentare de caz

Abstract

Secondary biliary cirrhosis represents a particular form of cirrhosis developed secondary to repeated inflammation produced by the obstruction (partial or total) or narrowing of the extrahepatic bile ducts, leading to periportal fibrosis. Biliary cysts are cystic dilations involving the biliary tree at single or multiple segments of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts. Although the curative treatment is represented by surgery, patients require a long-term follow-up, because there is a permanent risk of developing cholangitis and, in time, even malignancies. We report the case of a 13-year-old patient with a history of choledochal cyst operated on at the age of 3 years old and with multiple obstructive gallstones operated on two months before presenting to our service for full assessment and the establishment of supportive treatment. In addition, the histopathological examination after surgery revealed histopathological liver changes suggestive of chronic cholestatic hepatitis with pre-cirrhotic features. The laboratory findings revealed elevated transaminase levels, cholestasis and hyperbilirubinemia, with negative antibodies for Ebstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis C and hepatitis B viruses. Ultrasound examination revealed a liver with a micronodular structure, and the transient elastography revealed a rigidity equivalent to stage F4 (METAVIR). We initiated supportive treatment with antibiotics, choleretics and vitamins, with nutritional support and monthly evaluations. The evolution has been progressively favorable, with transaminase levels almost in the normal range and cholestasis gradually reducing, with a spectacular return of the weight curve.Keywords

choledochal cystbiliary cirrhosischildRezumat

Ciroza biliară secundară reprezintă o formă particulară de ciroză dezvoltată secundar inflamaţiei repetate produse prin obstrucţia (parţială sau totală) sau îngustarea căilor biliare extrahepatice, care determină fibroză periportală şi ulterior ciroză. Chisturile biliare sunt definite ca dilatări ale arborelui biliar la nivelul unuia sau mai multor segmente, atât extrahepatice, cât şi intrahepatice. Deşi intervenţia chirurgicală reprezintă tratamentul curativ, pacienţii necesită o urmărire îndelungată, din cauza riscului permanent al apariţiei angiocolitei şi, în timp, chiar a progresiei spre malignizare. Prezentăm cazul unei fete în vârstă de 13 ani, cunoscută cu chist de coledoc operat la vârsta de 3 ani şi cu litiază biliară obstructivă multiplă operată cu două luni anterior prezentării în serviciul nostru. Examenul histopatologic după intervenţia chirurgicală a evidenţiat modificări sugestive pentru hepatită cronică colestatică cu caracteristici precirotice. Examinările paraclinice au decelat la prima prezentare un sindrom de hepatocitoliză, colestază şi un sindrom bilioexcretor uşor, cu anticorpi negativi pentru virusul Ebstein-Barr, citomegalovirus şi virusurile hepatice B şi C. Ecografic se decelează un ficat micronodular, cu structură inomogenă, iar elastografia tranzitorie arată o rigiditate echivalentă cu stadiul F4 (METAVIR). Am iniţiat tratament de susţinere cu antibiotic profilactic, coleretice, protectoare hepatice şi vitamine, cu suport nutriţional permanent şi cu evaluări clinice şi paraclinice lunare. Până în prezent evoluţia a fost progresiv favorabilă, sindromul de hepatocitoliză s-a remis aproape în totalitate, iar sindromul de colestază se reduce treptat, cu o revenire spectaculoasă a curbei ponderale.Cuvinte Cheie

chist de coledocciroză biliarăcopilIntroduction

Choledochal cyst (CC), a rare congenital malformation of the biliary tract which accounts for 1:100,000 to 1:150,000 cases worldwide, presents as the early dilation of extrahepatic and/or intrahepatic bile ducts. Although the cause remains unclear, it is generally believed that complex mutations in multiple genes lead to CC(1,2). According to Todani, choledochal cyst can be anatomically classified into five major types (I-V)(3) – Figure 1. Type I cysts are the most commonly encountered in children (60-80%) and demonstrate either cystic (IA or IB) or fusiform (IC) dilation of the extrahepatic duct(4). The management is generally guided by cyst classification, but it is usually represented by surgery (cholecystectomy, choledochocystectomy and standard Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy), with regular follow-ups, because patients are at a high risk of developing choledocholithiasis, cholangitis and even cholangiocarcinoma in time(5). On the other hand, repeated inflammation arises from long-term biliary tract obstruction or narrowing induces periportal fibrogenesis. In time, this process causes hepatic nodule formation, leading to secondary biliary cirrhosis(6). As biliary fibrosis and cirrhosis morphogenesis follow the described pattern in all instances, biliary cirrhosis could be considered portal cirrhosis(7). As a result, patients with secondary biliary cirrhosis are at risk of developing the same complications as patients with any other type of cirrhosis (portal hypertension, infections, bleeding, malnutrition or hepatic encephalopathy).

Case report

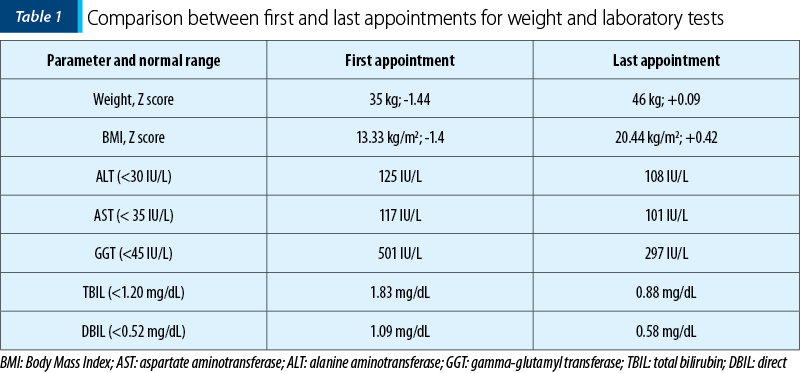

We report the case of a 13-year-old girl with a history of choledochal cyst, with surgery at the age of 3 years old, and multiple obstructive gallstones with surgery two months before presenting to our service. The girl was initially diagnosed at the age of 3 with CC type IC and, at that moment, the treatment was represented by choledochocystectomy and hepaticojejunostomy. After the initial surgery, the evolution was favorable, with the resolution of symptoms and clinical improvement. These patients require periodic follow-ups postoperatively. Unfortunately, our patient was lost from followed-up, and there was no surveillance and eventual prophylaxis to avoid complications that may appear in time. In evolution, at the age of 13 years old, she presented to an emergency service with an altered general condition, intense jaundice, pruritus, severe abdominal pain, dark urine and acholic stools. After further investigations, multiple obstructive gallstones and fulminant liver failure were diagnosed. The surgeons removed approximately 70 gallstones from her biliary tree (Figure 2). The histopathological examination of the liver revealed changes suggestive of chronic cholestatic hepatitis with pre-cirrhotic features. After discharge, the patient was referred to our clinic for full assessment and establishment of supportive treatment. At the first visit to us, the clinical exam revealed a girl with a relatively good general condition, with normally colored teguments, fatty tissue poorly represented, without cardiac and pulmonary changes, soft abdomen, insensitive, hypertrophic scar with keloid appearance at the level of the epigastrium, without signs of bacterial superinfection (Figure 3), liver at 1.5 cm below the rim and spleen not palpable. The laboratory tests revealed elevated levels of transaminases (alanine aminotransferase [AST] 125 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase [ALT] 117 IU/L), cholestasis (alkaline phosphatase [FA] 457 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT] 501 IU/L) and direct hyperbilirubinemia ([DBIL] 1.09 mg/dL, [TBIL] 1.83 mg/dL), hypercholesterolemia (283 mg/dl) and negative antibodies for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis C and hepatitis B viruses.

Ultrasound examination revealed a liver with a micronodular structure, and the transient elastography (FibroScan, Echosense, France) revealed a rigidity equivalent to stage F4 (METAVIR). We initiated a therapeutic plan including choleretics (ursodeoxycholic acid to reduce cholestasis syndrome), antibiotics (trimephoprime-sulphametoxazole in the prophylactic dose to prevent possible subsequent episodes of angiocolitis) and vitamins to support the patient. Because the patient had a moderate form of protein-caloric malnutrition at admission (Body Mass Index [BMI] 13.33 kg/m2, Z score -1.4), a nutritional plan designed in collaboration with a nutritionist was put in action to correct the weight deficit and, at the same time, to support the patient during the growth period. With this treatment, the evolution of the patient was progressively favorable. We performed monthly check-ups, both with clinical and paraclinical evaluations. At the last appointment, we compared the first results of the patient with the last ones in our clinic. During the seven months, we observed and treated the patient, and the transaminase levels and the cholestasis syndrome continued to decrease, with almost complete normalization of the bilirubin and cholesterol levels. Regarding the initial protein-caloric malnutrition, the patient managed to combat malnutrition under the appropriate nutritional regimen and vitamin support. At the last control, she had a normal weight with BMI of 20.44 kg/m2 (Table 1).

Discussion

Choledochal cyst is a congenital malformation of the biliary tract consisting of one or multiple cystic dilations on either at the intrahepatic or extrahepatic level(8). It is more common in females and represents the second most common type of bile duct malformation after biliary atresia(9). In terms of clinical manifestations, the typical presentation of this condition is nonspecific, with clinicians requiring a high level of suspicion while investigating patients with jaundice, vomiting, abdominal pain or, in some cases, a palpable abdominal mass(10). Due to this relatively vague clinical presentation, proper imaging studies are crucial for its diagnosis. Ultrasonography is usually the preferred initial imaging modality, with good sensitivity, giving valuable information about the cyst location, dimension and echotexture. However, when the common bile duct is dilated, ultrasonography fails to identify the cysts, so either a computed tomography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is recommended(11).

The treatment depends on the cyst type and the extent of hepatobiliary pathology, but in most cases it consists of cyst resection with bile flux restoration. It has historically been typical for types I, II and IV to undergo a cysto-enterostomy, which resulted in recurrent cholangitis and stenosis(12). The most accepted surgical approach in current practice involves cholecystectomy and excision of the enlarged biliary duct followed by hepatoduodenal or hepatojejunal anastomosis(13). Various complications can develop following surgery, including bile duct injury, strictures in the bile ducts, hepatic atrophy, cholangitis and intrahepatic lithiasis. The cause of biliary cholestasis is not only anastomotic stenosis and intrahepatic bile duct stenosis, but also the dysfunction of the Roux-en-Y. In time, hypertension, fibrosis or even secondary biliary cirrhosis may develop, enhanced by prolonged biliary obstruction associated with recurrent cholangitis(14). Even though there has been evidence that patients with CC Todani IVA have a higher risk of developing cholestasis (bile stasis) and hepatolithiasis, patients with other types of choledochal cyst can also develop complications, especially at a distance from the surgical intervention(3). Despite being less common than in adults, benign anastomotic strictures after surgery with recurrent cholangitis can still be observed in 10-25% of children. They can be associated with intrahepatic and bile duct stones(15).

Recurrent cholestasis enhances periportal, then portal fibrosis, associated with ductal proliferation, leading to secondary biliary cirrhosis. Several studies have shown that secondary biliary cirrhosis usually develops over time, varying with the cause of biliary obstruction. The average interval between biliary obstruction and cirrhosis is 7.1 years for common bile duct strictures and 4.6 years for common bile duct stones(16). As a result of a prolonged period of biliary stricture, calculous obstruction and repeated cholangitis, secondary biliary cirrhosis may result in liver failure and portal hypertension, leading to bleeding esophageal varices, hypersplenism with pancytopenia, ascites and encephalopathy(17).

Hence, the importance of long-term follow-up is crucial. Our patient’s complications occurred over time, because she was not monitored after the first surgery. As a result, both clinical condition and liver function have deteriorated substantially. Despite the absence of short-term complications (infections, anastomosis dehiscence, leaks), the patient had to be monitored for a long term for complications such as strictures, cholangitis, hepatolithiasis, or even cholangiocarcinoma. As we have seen, from the moment of the first surgery for the choledochal cyst, within 10 years, the patient has acquired multiple stones in the biliary tract that have produced essential liver changes, with the development of cirrhosis and signs of portal hypertension. A therapeutic plan is essential in such cases to prevent disease progression. The approach should be multidisciplinary, with a close collaboration between the pediatric gastroenterologist, surgeon, nutritionist and psychologist. Even though the emphasis was only on the disease itself in the past, a more holistic care model has evolved over the last few decades for children with chronic diseases. It emphasizes functional outcomes and the quality of life(18). Many factors influence the outcome and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis, some of which are related to the individual’s general health, the nature of their social relationships, social support and access to coordinated care(19). Children, especially teenagers, are the most prone to psychological distress, especially when they have a chronic illness that prevents them from being as active as other children of the same age. For this reason, adequate psychological support throughout the treatment and recovery process is essential. The successful evolution of the patient over the past 10 months makes us believe that our multidisciplinary team has developed an optimal plan for our patient. We will keep the patient under regular follow-ups and strict treatment, with a possible spacing of the interval between checkups, constantly vigilant on possible new complications.

Conclusions

Choledochal cyst is a congenital malformation that requires constant follow-up, even though early surgery has been performed and symptoms have resolved. Long-term complications are often devastating, even up to cirrhosis, affecting the child’s health and the quality of life. An important aspect highlighted by this case is that the follow-up after surgery is crucial to avoid chronic illnesses in liver and bile duct pathology. Hence, a multidisciplinary approach and an optimal treatment targeting all the systems involved are the key to an almost normal life, without further long-term morbidities.

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY

Bibliografie

- Hoilat GJ, John S. Choledochal Cyst. 2022 Aug 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557762/ [accessed in 14.12.2022].

- Ye Y, Lui VCH, Tam PKH. Pathogenesis of Choledochal Cyst: Insights from Genomics and Transcriptomics. Genes (Basel). 2022 Jun 8;13(6):1030. doi: 10.3390/genes13061030.

- Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977 Aug;134(2):263-9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2.

- Ronnekleiv-Kelly SM, Soares KC, Ejaz A, Pawlik TM. Management of choledochal cysts. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016 May;32(3):225-31. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000256.

- Farello GA, Cerofolini A, Rebonato M, Bergamaschi G, Ferrari C, Chiappetta A. Congenital choledochal cyst: video-guided laparoscopic treatment. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995 Oct;5(5):354-8.

- Sikora SS, Srikanth G, Agrawal V, Gupta RK, Kumar A, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Liver histology in benign biliary stricture: fibrosis to cirrhosis... and reversal? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Dec;23(12):1879-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04901.x.

- Leevy CM, Popper H, Sherlock S. Diseases of the Liver and Biliary Tract: Standardization of Nomenclature, Diagnostic Criteria, and Diagnostic Methodology. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976.

- Bhavsar MS, Vora HB, Giriyappa VH. Choledochal cysts: a review of literature. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(4):230-6.

- Le L, Pham AV, Dessanti A. Congenital dilatation of extrahepatic bile ducts in children. Experience in the central hospital of Hue, Vietnam. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006 Feb;16(1):24-7. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873071.

- Imazu M, Iwai N, Tokiwa K, Shimotake T, Kimura O, Ono S. Factors of biliary carcinogenesis in choledochal cysts. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001 Feb;11(1):24-7. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12190.

- De Angelis P, Foschia F, Romeo E, Caldaro T, Rea F, di Abriola GF, Caccamo R, Santi MR, Torroni F, Monti L, Dall’Oglio L. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in diagnosis and management of congenital choledochal cysts: 28 pediatric cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2012 May;47(5):885-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.01.040.

- Dhupar R, Gulack B, Geller DA, Marsh JW, Gamblin TC. The changing presentation of choledochal cyst disease: an incidental diagnosis. HPB Surg. 2009;2009:103739. doi: 10.1155/2009/103739.

- Santore MT, Behar BJ, Blinman TA, Doolin EJ, Hedrick HL, Mattei P, Nance ML, Adzick NS, Flake AW. Hepaticoduodenostomy vs hepaticojejunostomy for reconstruction after resection of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2011 Jan;46(1):209-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.092.

- Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, Sauter PA, Coleman J, Yeo CJ. Postoperative bile duct strictures: management and outcome in the 1990s. Ann Surg. 2000 Sep;232(3):430-41. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00015.

- Soares KC, Goldstein SD, Ghaseb MA, Kamel I, Hackam DJ, Pawlik TM. Pediatric choledochal cysts: diagnosis and current management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017 Jun;33(6):637-650. doi: 10.1007/s00383-017-4083-6.

- Negi SS, Sakhuja P, Malhotra V, Chaudhary A. Factors predicting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. Arch Surg. 2004 Mar;139(3):299-303. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.299.

- Jeng KS, Shih SC, Chiang HJ, Chen BF. Secondary biliary cirrhosis. A limiting factor in the treatment of hepatolithiasis. Arch Surg. 1989 Nov;124(11):1301-5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410110059012.

- de Kleine RH, Ten Hove A, Hulscher JBF. Long-term morbidity and follow-up after choledochal malformation surgery; A plea for a quality of life study. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2020 Aug;29(4):150942. doi: 10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2020.150942.

- Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, Younossi ZM. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013 Jan;15(1):301. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0301-5.