Fundaments of psychoanalytic psychotherapy

Fundamentele psihoterapiei psihanalitice

Abstract

Introspection and psychodynamic defence mechanisms will remain explanatory bases in any Kaplan-type textbook, alongside genetic, biochemical foundations (related to neuromodulators and neurotransmitters) or social perspectives. This paper aims to explain both classical Freudian psychoanalysis and its underlying concepts, as well as modern Patrick Casement-like postulates on the principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Active listening, floating attention, Freud’s first and second theories of anguish, the classical view of the division of intrapsychic functioning into neuroses, psychoses, borderline functioning and perversions, the original reflex as the core of unconscious attraction, primitive mechanisms, such as denial, projection, projective identification and dissociation, together with the foreclosure in obsessive compulsive disorder or mature mechanisms, such as humor, intellectualization, rationalization and activism, represent the bridge between the semiological realm of psychiatry and the key to psychodynamic explanations, the gateway to the area of psychotherapies.Keywords

psychoanalysispsychodynamic principlesexplanatory theorieseconomictopical and dynamic viewpointsRezumat

Introspecţia şi mecanismele de apărare psihodinamică vor rămâne baze explicative în orice manual de tip Kaplan, alături de fundamentările genetice, biochimice (legate de neuromodulatori şi neurotransmiţători) sau de perspectivele sociale. Lucrarea de faţă îşi propune să expliciteze atât psihanaliza clasică freudiană şi conceptele care au stat la baza acesteia, cât şi postulatele moderne, precum Patrick Casement, referitoare la principiile psihoterapiei psihanalitice. Ascultarea activă, atenţia flotantă, prima şi a doua teorie a angoasei ale lui Freud, perspectiva clasică a împărţirii funcţionării intrapsihice în: nevroze, psihoze, funcţionări limită şi perversiuni, refulatul originar ca nucleu de atracţie inconştientă, mecanismele primitive precum negarea, proiecţia, identificarea proiectivă şi disocierea, alături de forcluderea din tulburarea obsesiv-compulsivă sau de mecanismele mature precum umorul, intelectualizarea, raţionalizarea sau activismul, reprezintă puntea de legătură între tărâmul semiologic al psihiatriei şi cheia explicaţiilor psihodinamice, poarta de intrare în arealul psihoterapiilor.Cuvinte Cheie

psihanalizăprincipii psihodinamiceteorii explicativepuncte de vedere: economictopic şi dinamicPsychotherapy, as applied by specialists, differs from empirical approaches (advice from relatives or friends). Psychotherapy involves the systematic and conscious application of psychological means of influencing behavior.

Psychotherapy is based on the assumption that, even in the case of a somatic pathology, the way in which the subject perceives and evaluates his or her condition, as well as the adaptive strategies he or she uses, play a role in the evolution of the disorder, and these new strategies must be modified if the condition is to evolve favorably.

At the heart of all psychotherapy is the belief that the person with psychological problems has the capacity to change, learning new strategies for perceiving and evaluating reality, as well as new strategies for behavior.

The objectives of any psychotherapy are both to understand the patient and to modify, so that the patient’s existential difficulties are removed or diminished.

To this end, the psychotherapist carries out an assessment of the patient, seeking to highlight the patient’s psychological characteristics and problems.

The therapeutic approach will have the task of freeing the patient from psychological and psychosomatic symptoms (depression, anxiety, somatoform complaints), as well as from feelings that disturb his/her existence and have negative effects on the entourage and on important areas of the individual’s life (professional activity, interpersonal relationships, sexual life, self-image, self-worth, integration into the collective).

Psychotherapy is defined by most specialists as a systematized, planned and intentional psychological action, based on a well-developed conceptual theoretical system and exercised by a qualified psychotherapist on the patient.

Psychotherapy uses specific methods and means, and is not to be mistaken for a simple warm and empathetic action exercised on an empirical level by a relative, friend or priest.

Psychotherapy should also be seen as an interpersonal patient-psychotherapist relationship, designed to investigate and understand the nature of the patient’s disorders, with the aim of correcting them and freeing the patient from suffering.

Mental distress can manifest itself in the form of attitudes, feelings, behaviors, symptoms or clusters of symptoms that create the patient’s distress and which the patient wants to get rid of.

However, the objective of most psychotherapies is to produce profound changes in the psychological area, and not just a simple reduction of symptoms. These changes will help the patient to achieve a more stable and effective adaptation to the environment. Not all systems of psychotherapy have such demanding goals.

Although psychotherapy targets the symptom, the difficulty, the mental or psychosomatic illness, it should not be reduced to the simple process of healing and should aim at deep restructuring in the psychological, self-regulatory, preventive and self-formative sphere, aiming not only at healing but also at evolution.

Strupp and Hadley(25) (1977) show that the psychotherapeutic success can be judged by three criteria:

-

Subjective patient experience = disappearance of symptoms, the patient feels better, is more satisfied, happier, more at peace with him/herself.

-

Social recognition = patient’s progress in profession, education or family.

-

Materialization of psychotherapeutic expectations in terms of changes in the psychological sphere and in the subject’s life.

Many patients can feel at least temporarily relieved when they have managed to get rid of the unpleasant symptom that made them turn to the therapist.

The success expected by the therapist is more difficult to achieve and to evaluate, especially in the case of analytically oriented therapies where the mere disappearance of the symptom is not considered sufficient, as it is not synonymous with the deep restructuring of the neurotic impulses.

Although the patient states that he/she is feeling better, the therapist may consider that the patient’s positive state is transient, the result of a positive transference, and that this state may return. The analytic therapist may consider the improvement of the symptom to be a non-semantic part of the desired change.

Specialists in brief psychotherapies are less demanding, contenting themselves with solving the problems for which the patient comes (e.g., drug treatment).

As a scientific approach, psychotherapy must be based on clearly formulated hypotheses and on a system of well-established rules that derive from the theoretical conception of the psychotherapeutic school of human psychology and its psychopathological disorders.

The psychotherapist must know the fundamental laws of the functioning of psychological subsystems, clearly formulate his/her goals and the steps to achieve them, as well as the appropriate strategies of action for each patient.

Most specialists believe that the goals of psychotherapy aim at:

Getting the patient out of the existential crisis in which he/she finds him/herself.

-

Eliminating or reducing symptoms.

-

Strengthening the patient’s ego and integrative capacity.

-

Modifying or restructuring of the patient’s intrapsychic conflicts.

-

Changes in psychological structure to achieve a more mature functioning, with a more effective coping capacity.

-

Reducing or eliminating, if possible, those environmental conditions that generate or maintain maladaptation.

-

Changing the subject’s misconceptions about themselves and the world around them.

-

Developing a clear sense of personal identity in the subject.

Common factors in psychotherapy systems

Parloff(20) (1975) described the existence of over 140 well-developed, conceptually and methodologically sound psychotherapeutic systems. Although proponents of each therapeutic school claim that their system is the best, it can be seen that the differences between schools are not so great.

In the 1940s, Rogers(22) (1942) and Thorn(26) (1948) found that there were common elements in different types of psychotherapy:

-

The relationship between patient and psychotherapist.

-

Free and open expression of the patient’s emotional experiences, intuitive understanding, insight into the patient’s personal problems.

-

The idea of the psychological development of the patient, of the updating of latent capacities of his/her psychological evolution in the sense of acquiring new patterns of behavior, leading to a higher level of adaptation in the psychological area.

Aspects that differentiate psychotherapy systems

Wittkower(30) (1974) and Werner(29) (1995) point out that, although it is unfortunate that there are common features of the various systems of psychotherapy, the differences between them should not be minimized. These differences are particularly emphasized by the creators of psychotherapy systems, who feel the need to distinguish themselves from other psychotherapists. There have been and there are experiments that have attempted to compare different psychotherapy systems with each other. Thus, it has been concluded that analytically oriented therapies differ from behavioral therapies, both in theory and in terms of the techniques applied.

Another issue that arises is that not every type of treatment or psychotherapeutic approach is suitable for every individual and every psychotherapeutic system.

In 1963, Watson(28) described some of the main criteria according to which psychotherapeutic systems can be delineated:

-

Psychotherapy is seen by some specialists as a scientific approach and by others as an art. As practiced today, psychotherapy has its roots in ancient cultures and still bears the mark of archaic traditions. Even today, psychotherapy is not fully scientific (according to some). The variables are so complex and their interdependence so intricate that the experience with each patient can be considered unique.

-

Psychotherapy does not possess a systematic, unified approach to the patient’s problems. There is no standard conception of the nature of psychotherapy that is accepted by most specialists.

-

The personality of the psychotherapist is an important factor in the development of the interpersonal relationship that psychotherapy involves. The favorable or unfavorable results of psychotherapy depend on the particular characteristics of the practitioner. It has even been said that a talented psychotherapist will achieve good results even if he or she has poor technique. Differences of opinion within some schools of psychotherapy (between psychoanalysts) are due to differences in psychology between them.

In 1940, Oterdorf pointed out that the differences in emphasis that different psychoanalysts place on aspects of psychoanalytic doctrine and practice are based on elements of talent and clinical skills displayed by each therapist. The psychotherapist’s desires and expectations set both the goals of psychotherapy and the psychological patterns that should constitute the outcome of psychotherapy (the differences between psychic reconstruction therapies and symptom-centered therapies).

-

Differences between the various therapeutic schools in terms of basic training and professional training of the therapist. These differences are highlighted by the fact that a psychiatrist, for example, tends to approach patients with more severe disorders, whereas a psychologist tends to approach milder cases.

-

The procedures and methods applied during psychotherapy depend not only on the therapist’s psyche, but also on that of the patient, as well as on the conditions of the psychotherapy and the severity of the symptom. The methods and techniques applied to a student are different from those applied to a terminally psychotic patient.

Knight(16) (1942) described the limiting factors involved in achieving the goals of analytic psychotherapy and other psychotherapeutic systems.

-

Patient’s intellectual level. A patient’s cognitive efficiency may be improved if the patient has fewer neurotic features, but the IQ is a limiting factor.

-

Expectations related to the patient’s various abilities or skills that can be upgraded through psychotherapy. As in the case of cognitive efficiency, one can only hope to unlock those pre-existing abilities of the subject.

-

The success of psychotherapy is also limited by the difficulties, stresses and problems of everyday life. Even a very well analyzed patient can decompensate if the amount of stress exceeds a limit.

-

Patient’s socioeconomic status which limits access for a wide range of people, especially to long-term therapy.

-

Hlan differentiates the following ways of using the therapeutic relationship:

-

Authoritative – the therapist tells the patient what to do, sets plans, rules, schedules. It is common in behavioral therapy. Another indirect form of use is suggestive therapy.

-

Causal (genetic) – the therapist tends to use the therapeutic relationship to get to the source of the patient’s conflicts and difficulties. It usually aims to highlight those unconscious contents that generate neurotic symptoms (analytical model of approach).

-

The relationship is seen as a direct, immediate, lived experience. The psychotherapist begins by approaching the patient as they are at that moment. An attempt is made to reactualize latent availabilities – the noncritical approach. The therapist shows understanding for the patient’s problems, but the focus is on what needs to be done from now on, not on the patient’s life history.

Other differences between the various schools relate to the need for psychodiagnosis before starting psychotherapy. While most believe that prior psychological knowledge of the patient is absolutely necessary, there are also opposing views.

Rogers rejects psychodiagnosis because “it’s too authoritarian”. His assessment may be valid in neurotic or psychosomatic conditions, but it cannot be applied to suicidal or psychotic patients (Rogers, 1961)(21).

In 1975, Harper reviewed over 30 systems of psychotherapy and divided them into two broad categories(13):

-

Psychotherapies mainly focused on the emotional-affective side.

-

Cognitive psychotherapies.

Rychlak (1969) classified psychotherapeutic systems according to their underlying philosophical conception(24):

-

Mechanistic-behavioral psychotherapies.

-

Humanistic psychotherapies.

Watson discusses the differences that exist between reconstructive and supportive psychotherapies; between depth and symptom-focused psychotherapies. The term reconstructive psychotherapy is used for those psychotherapeutic techniques that aim to modify psychological structure (Watson, 1940)(27).

Supportive psychotherapies do not have such objectives, but only support the patient in the crisis situation.

The demarcation between the two categories of psychotherapy is relative because reconstructive therapies contain supportive elements and supportive psychotherapy can sometimes lead to reconstruction of the psyche.

-

Reconstructive psychotherapy is also called disclosure or insight psychotherapy.

-

Supportive psychotherapy is also called cover therapy. The patient is helped by various methods (encouragement, hypnosis, suggestion) to forget problems and stressful situations and to ignore or repress their difficulties.

It should be stressed out that supportive elements, whether central or peripheral, are present in any psychotherapy. What is commonly understood by counseling is nothing other than supportive psychotherapy. Counseling usually involves fewer sessions, deals with reactive disorders, and less with serious intrapsychic conflicts, addressing less severe cases.

The aim of supportive psychotherapy is to help the patient live more adaptively to their own difficulties and to guide them through a period of stress.

Frank(8) (1961) and Alexander(1) (1954) state that supportive psychotherapy is indicated in two opposite categories of situations:

-

When there is no need to change the patient’s psychology, the effectiveness being only temporarily disturbed by unfavorable external conditions.

-

The disturbance is so strong that it is hard to assume that there could be any structural change in the patient.

Symptom-focused psychotherapies versus depth psychotherapies

The symptom is the patient’s spontaneous and often unconscious attempt to adapt to life’s difficulties. The clinician often regards them not as significant in themselves, but as an indicator of a deeper maladjustment.

The symptom is the way in which conflicts of an unconscious nature are expressed.

If the mental structure is balanced, the symptom spontaneously remits. Although the symptom is not the ultimate goal of in-depth psychotherapy, it is no less important for the patient.

Due to the importance the patient attaches to the symptom, symptom-focused psychotherapy has emerged, with more modest goals – the elimination or reduction of the symptom.

Symptom-focused therapies are indicated in the following situations:

-

The patient does not have the financial resources or time to undergo in-depth therapy.

-

The therapist believes that in-depth therapy can be dangerous for the patient (potentially psychotic).

-

The symptom is not so disabling so that it blocks the person’s life and activity.

By freeing oneself from the symptom, the individual gains a certain freedom of action. In many cases, this liberation may be the only reason for the patient to see the therapist. It is possible that the removal of the symptom may produce a symptom substitution, leaving the patient without an adequate way of adapting to psychotraumatic situations. These cases are rare.

Frank(7) (1971) believes that symptom-centered psychotherapeutic treatment should not be minimized because:

-

A frontal attack is made on the psychopathological process.

-

Removing the symptom can facilitate a subsequent in-depth psychotherapy approach to resolve the underlying disorder.

-

Removing the symptom leads to the disappearance of second-order emotional disturbances (secondary to the symptom).

-

Once the symptom has been removed, there is a positive change in the patient’s attitude towards the psychotherapist and psychotherapy.

-

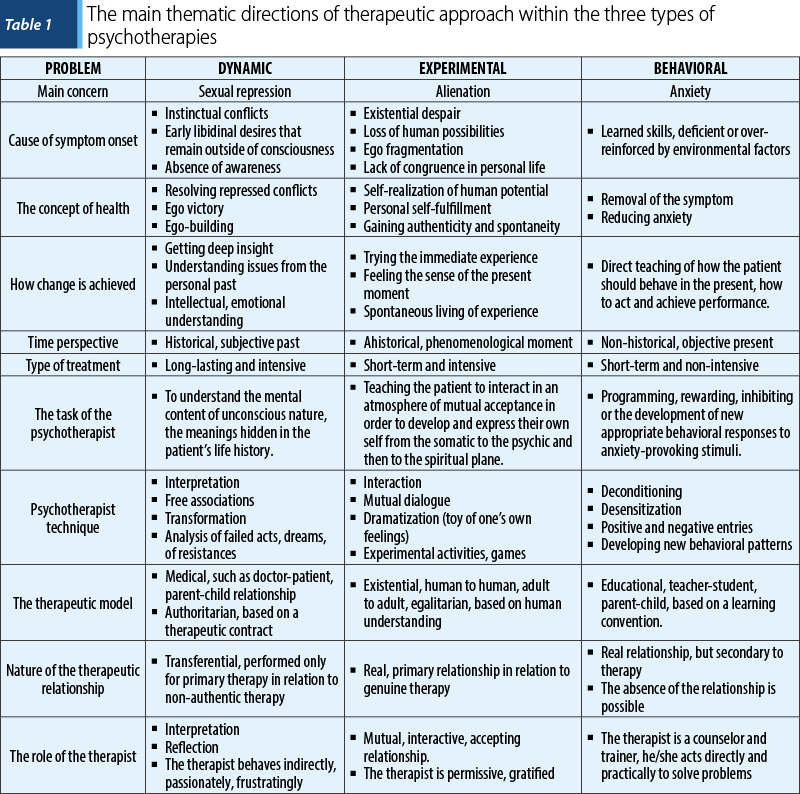

Karasu(15) (1980) classified psychotherapeutic systems according to three basic components. Each therapeutic school pivots around one of the following approaches:

-

Dynamic

-

Behavioral

-

Experiential.

Each concept represents a thematic field and a reference system in relation to which human nature, psychopathological symptomatology, the curative approach and the nature of the therapist-patient relationship are interpreted and oriented (Table 1).

Psychodynamically oriented psychotherapy

Dynamics in psychology has its origins in physics and is based on the idea that any psychic phenomenon is the result of the interaction of forces and that the human being is a complex structure determined by the turbulent interactions of conflicting intrapsychic forces.

Psychodynamic psychotherapies, psychoanalysis and its derivatives, as well as other psychotherapeutic systems – those of existentialist orientation – are based on this idea.

Lazarus called these dynamic therapies insight-based therapies (Lazarus, 1971)(17).

Karasu states that, although dynamic elements appear within some existentialist schools, their general characteristics make them belong to the experiential orientation (Karasu, 1980)(15).

Dynamic therapies focus on the patient’s discovery of various psychological processes of an incipient nature, processes that underlie psychological structuring, adaptive phenomena and the production of feelings. These sudden and intuitive discoveries are called Id. It is through Id that the patient discovers the hidden reasons and causes behind their behavior and problems.

The main task of dynamic therapy is to help the patient discover what is happening to him and to use the understanding gained to change the disruptive style of reacting and behaving.

This orientation has its origins in Freudian psychoanalysis, but has been modified by other psychotherapeutic systems. These systems are similar in the theory that the psychotherapist must reveal to the patient what is wrong and starting from this discovery help him/her to develop new patterns of effective behavior.

Dynamic therapies have two common features:

1. Patient discussion as a basic tool in therapy. In general, it is the patient who decides what to talk about. The therapist can influence the patient’s decisions directly or indirectly, but most Id-based therapies downplay his or her role, although there are exceptions. In Id-based therapy, the patient is at the center of the therapy.

2. The therapist tends to adopt a professional attitude rather than a personal one, asking for data about the patient’s problems without acting as a friend.

There are differences in the strategy and tactics of the therapeutic approach.

Orthodox psychoanalysis involves five sessions a week, over a period of several years.

Neo-Freudians support a shorter period (months or weeks), with one session per week.

The basic principle or key to this therapy is the notion of Id. The patient has goals in life, attitudes, motives, opinions, in relation to his/her own person that he/she is aware of and strives to follow. He/she also possesses an unconscious set of motives and conflicts originating in his/her childhood relationships and conflicts. In the adult, this unconscious content can be harmful because:

-

They are specific to child-like relationships, relationships that do not exist today. These relationships are characterized by immaturity and self-centeredness.

-

Being unconscious, they operate from the shadow, but effectively on the present state, escaping rational control.

The patient can no longer be the person he/she would like to be because, unconsciously, he/she wants to do incompatible things at the same time and is in conflict with him/herself and those around him/her. The patient’s solutions are ineffective because they put into action defensive mechanisms that represent unrealistic ways of coping generated by the disturbance. These disturbances can be expressed in the form of emotional directions: anxiety, depression, somatoform complaints and conversive disorders. The symptom brings the patient to the therapist. For the patient, the symptom is the disorder for which he or she feels in need of treatment.

Id-based therapies consider symptoms to be surface elements, less important than the hidden forces that produce them. The paradox is that the patient comes to get rid of the symptom and the therapist considers them as secondary.

Id therapy gives rise to great difficulties – the goal of dynamic therapy is not the goal of the patient.

This therapy has two objectives:

-

To form the patient a new way of understanding themselves.

-

To change the patient’s view of their problem – in fact, their way of life.

It is difficult to know whether the patient really had IN on their own problem. Each theorist understands it in their own way, because they perceive psychological differences differently.

Problem solving occurs when there is a correct Id, which can be judged in terms of the elimination of symptoms and psychological restructuring that will adopt more effective patterns of behavior.

It is not the theoretical concept of Id that matters, but the belief that the patient has found the right answer.

In brief therapies, what is noted is the disappearance of symptoms, while dynamic therapies use more sophisticated criteria to assess psychotherapeutic success, criteria loaded with subjectivism: deeper self-understanding, experiencing a sense of personal happiness, establishing more effective and more affective interpersonal relationships.

Freudian psychoanalysis

It is the most representative psychodynamic type of therapy and it refers to the conceptual system and psychotherapies directly inspired by the work of Freud and his followers.

The psychoanalytic perspective is based on the following fundamental principles:

-

The idea that the human being possesses a series of instinctive impulses and tendencies of an incipient nature and the concern for how these impulses are expressed, transformed or repressed. Repression occurs in order not to allow painful affections to reach the threshold of the concrete.

-

The belief that repression is based on sexual tendencies and that these psychological disorders originate from defective libidinal development.

-

The idea that defective psychosexual development originates from early childhood conflicts and psychotraumas, especially the Oedipus complex.

-

Conviction about the universal and permanent character of the Oedipus complex that remains active and unacknowledged.

-

The idea that man is confronted with conflicts between biological drives (identity) and its substitutes – primary defence mechanisms of the Ego that attempt mediation with external reality – Ego in accordance with the moral standards developed by the society – Superego.

-

Psychoanalysts believe in intrapsychic determinism – phenomena and behaviors are strictly determined by previous events which, if not acknowledged, cause the patient to repeat the same maladaptive pattern over and over again.

For the analytic psychotherapist, the objective is to bring the unconscious into the concrete – i.e., to help the patient to become aware of the content of the drive in the deep areas of the psychism. The psychotherapist analyzes the content of instincts and drives, especially of a sexual nature, seeking to remove the patient’s natural resistances.

The process of analytical orientation is long, sometimes endless, its objective being too pretentious: the resolution of all neurotic conflicts.

The most important aspect is the resolution of conflicts, which is considered necessary for a healthy psychology, the healing meaning the acquisition by the patient of a total control of the ego, of the impulses of the Id.

The therapeutic process is marked by the moment of catharsis, which Harper defines as a release of tension and anxiety through the psychological reliving of past experiences (Harper, 1959)(14).

Instead of the term purification, used by various religious systems, Freud preferred the term catharsis (Breuer, 1936)(3). From the beginning, catharsis was considered as the basic element of psychotherapy, later Freud himself came to the conclusion that, for a successful psychotherapy, catharsis is not enough, and he shifted the emphasis to the other elements of analysis.

The catharsis is still important because:

-

Therapy cannot progress if the patient does not express his/her emotional feelings openly.

-

Expressing these feelings gives the patient a sense of relief, which leads him/her to trust the therapist.

Although both processes – catharsis and Id – are regarded as belonging to traditional psychotherapy, it should be pointed out that Freud never used the term Id as such (Freud, 1947)(10). The therapeutic process shifts its focus in the course of evolution from the moment of retrieval of forgotten memories.

Hutchinson (1950) stated that there are four successive stages in achieving Id in psychotherapy:

-

The preparatory stage is characterized by feelings of frustration, anxiety, inner emptiness, followed by a feverish search through trial and error for solutions to one’s problem, followed by a relapse into old patterns of behavior, with the patient not finding a solution to his/her problem.

-

Incubation or withdrawal, as the patient tends to run away from the problem, showing lack of motivation or resistance to problem solving.

-

Enlightenment when the problem becomes clear and the solution is self-evident. The patient experiences a flow of ideas accompanied by a sense of reality Id.

-

Evaluation and development of the solution that is confronted with external validation criteria.

-

The therapist usually distinguishes between two types of Id:

-

Intellectual – with limited therapeutic value.

-

Emotional – essential.

The two types interact. Although Id has a major therapeutic role, we have to agree with Schonbar who said that not every change in the therapeutic sphere renders IN and not every Id necessarily leads to change.

Psychoanalysts believe that there is another important psychological factor that generates change – the transferential patient-therapist relationship.

Psychoanalysis techniques

The method of free associations

According to Freud, the subject on which the patient will freely associate is left to his/her own discretion, without encouraging a guiding thread of associations (Freud, 1958)(12).

The patient’s mind wanders, so he says whatever comes to his/her mind, regardless of convenience. Free association processes can be: memories, feelings, reproaches, images, daydreams, accusatory thoughts. Often the flow of free associations is blocked by the patient’s resistance. They are used because the unconscious will reveal repressed contents, freeing the patient from their effects. It is erroneous to say that the therapist does not use direct questions, but uses them as stimuli to trigger new free associations. For example: “What does this thought lead you to?” or “How old were you when this happened?”

Another aspect of the method of free associations is that as long as the patient associates freely on the subject of the transfer at the expense of the therapist, the associations remain untouched. When the patient uses resistance mechanisms it is time for the analysis to turn to the patient.

Dream analysis

The seemingly illogical nature of free associations is also characteristic of dreams. Dreams can be viewed deterministically as representing reactions to the dreamer’s unconscious experiences. Therapists have found that patients often refer spontaneously to their dreams. The narrated content represents a kind of kaleidoscopic screen, which only hides the real meaning of the dreams. The latent content is often represented by repressed feelings to which the patient has no access and in which he/she is deeply involved so that he/she cannot bring them into reality through personal effort.

The method of dream analysis consists in associating the patient not with the dream in its entirety, but with details that seem significant to him/her or to the therapist. In this way, specific themes which help to bring out the repressed contents emerge. The therapist must know the patient well and warn him/her that there is no universal symbolism of dreams that applies in every situation.

The most effective way to complete the analysis of a dream is to remember it until the repetitive content is continued and amplified in other dreams. It should be considered that the first dreams are easier for the patient to analyze and interpret due to their lack of complexity. The deeper the analysis, the more hidden areas are penetrated.

Analysis of patient’s actions

Nonverbal and unintentional verbal behavior are important elements for the analysis. These aspects can manifest themselves during psychoanalysis sessions, but also outside them. During the session, one can observe the patient’s looks, constant attempts to adjust their attire, different behaviors or missed acts. Outside the session, changes in the patient’s behavior in the family, at work, anxiety, changes in the way he/she treats his/her friends and family may occur.

Transfer and resistances

Transference and resistance are central points of therapy, considered by Freud as the means by which psychoanalytic therapy differs profoundly from other orientations (Freud, 1958)(12).

Transference refers to the patient-therapist relationship, which is irrational, projective and ambivalent. In psychoanalysis, this relationship is used therapeutically, explaining to the patient how it works and its roots in his or her life history. As long as the therapist maintains neutrality, most of the patient’s emotional reactions are not the result of present situations, but spring from their own hidden desires. Nowadays, this type of reaction leads to the discovery of early experiences that generated these desires. The therapist leads the patient to question the origin of his/her behaviors, an origin that has remained partly outside the concrete. With the emergence of IN, changes in the behavioral area are possible.

Analytical therapy consists of a series of IN that leads to another level of self-awareness. It represents a repetition of past experiences, which are transferred to the therapist. The patient lives these experiences by reliving affective states that were important to him/her in the past. He/she does not say how critical he/she was of his/her parents, but he/she is critical of the therapist.

In the early stages of psychoanalysis, it is possible that the patient’s symptoms disappear and the illusion of health is created. This is due to the release of anxiety, which occurs because of the patient’s trust in the therapist. This stage is called the transference cure and is transitory because the incipient processes have not yet been analyzed. The repetition of neurotic patterns of behavior in the relationship with the therapist is called transference neurosis.

The relationship is fixed on an irrational, emotional and regressive level. The therapist is seen as an omnipotent deity, the patient wanting to be loved by the therapist, even sexually. As the patient’s feelings are frustrated in concrete terms, anxiety and anger arise. If anxiety predominates, the patient will show a submissive attitude, trying to obtain favors from the psychotherapist. If anger predominates, the patient becomes aggressively vindictive, assertive and resentful. These attitudes must be corrected by the therapist because the patient cannot be realistic in his/her relations with the rest of the world if he/she is not realistic in his/her relations with the therapist.

In the therapeutic relationship, the patient has the opportunity to face the same difficulties that he/she has not mastered in the past: the mixture of envy with admiration and gratitude towards the father, older brother, rivalries, feelings of anxiety secondary to the experience of feelings of envy and hostility, dependence on the mother at the same time with frustration and resentment when the demands for love are not fulfilled, feelings of rebellion against maternal overprotection.

People who cannot live their past experiences are contraindicated for psychoanalysis. This category includes some psychopaths, psychotic patients, especially discordant ones.

For the therapist, the transferential relationship is important for two reasons:

-

It sheds light on childhood patterns of identification and some of the characteristics of the pacifist’s relationship with others. The therapist learns important elements about the patient’s psyche through the recall of early childhood relationships in the therapeutic relationship.

-

The therapist uses this relationship to encourage the patient to overcome unpleasant moments, because the patient’s dominant desire is to please the therapist. The therapeutic relationship helps to bring out psychological aspects that would otherwise be too difficult for the patient to tolerate. The therapeutic relationship must be developed in such a way that the patient sees it for what it is: a relationship with a childhood parent figure. The patient needs to let go of childhood and establish adult-like relationships with people in the entourage.

In a broad sense, resistance means any phenomenon that interferes with the natural course of therapy: the patient’s disapproval of the therapist’s interpretations and non-acceptance of them, the patient seeking to unconsciously resist the progress of the analysis. In the narrower sense, resistance manifests itself in the breach of the regression of the analysis and implicitly the non-sharing of all the therapist’s thoughts.

There are all sorts of ways in which resistance manifests itself:

-

Multiple and superficial associations.

-

Extended breaks in the flow of associations.

-

Delays and absences from therapy.

-

The appearance of new symptoms.

-

The possibility of falling asleep during therapy.

It is not difficult to understand why these resistances occur: the patient has managed to reach a kind of adaptation to cope with his/her problems, as he/she fights against the analytic approach because he/she feels his/her world is threatened.

The therapist’s task is to analyze the resistance in order to show the patient how it is preventing them from finding the cause of what is causing their discomfort.

Another type of resistance is represented by patient’s withdrawal from therapy. Overcoming this requires a strong transfer to the therapist. Towards the end of therapy, the therapeutic relationship weakens and the patient learns to rely on him/herself. From time to time, old tendencies are reactivated and will manifest themselves in feelings of frustration followed by new attempts to gain independence. Therapy succeeds when the patient’s ego becomes so strong that he/she can let go of his/her dependence on the therapist.

Countertransference. Psychoanalysis is an emotional experience for the patient and the therapist. The therapist may experience countertransference in which he or she responds emotionally to an emotional request from the patient.

The didactic analysis that the therapist has to do should prevent the occurrence of countertransference, but it is not perfect and there are still unexplored areas of the patient-therapist relationship. The therapist must learn to control his/her feelings without becoming unresponsive and lacking in human understanding.

Ego analysis

According to French, there is also a standard practice in psychoanalysis of not proceeding to the interpretation of the Id until both the conscious and the actual behavior analysis have been conducted, which can influence the enactment of the results of the various interpretations (French, 1952)(9).

In the course of Ego analysis, the therapist tends to understand what are the past roots of the current problems, but also aspects of the current life that are active at a given time.

Interpretations

As the sessions unfold, meanings and connections related to the patient’s underlying problem emerge. The analyst is the first to start revealing the content, the meanings of the information provided by the patient. The decision as to when an interpretation should be made is made according to the therapist’s assessment of whether the patient can cope with these interpretations. These judgements depend to a large extent on the understanding of the Ego’s defence mechanisms. Interpretations made too early by an inexperienced therapist can throw a pre-psychotic into crisis or an anxious person into panic. Interpretation is not an advice, a suggestion, an attempt to influence the patient or a projection of the therapist’s opinions and attitudes. Interpretations are not taboo, as their validity depends on their verification by the patient in the future reality.

Analytical interpretation consists of the therapist ordering the discontinuous material in the course of free associations and dream analysis, giving it a meaningful explanation through analytical concepts.

The art of interpretation aims to identify resistances as they arise and to make the patient aware of them. When the resistances are removed, the patient can move through free associations to address the repressed material by bringing its content into reality.

Psychoanalytic processing of patient-produced material

It is a process of continuing the analytic approach in the form of further specific interpretations, despite the patient’s failure to accept or emotionally assimilate the initial interpretations offered by the therapist. This process is very time-consuming, with many hours of psychoanalysis. The patient tends to revert to his/her infantile behaviors and the therapist is patient, rereading the proposed material from different points of view or becoming more active (Ferenczy, 1934)(6).

End of analytical cure

There are no standard answers to this question. Freud was of the opinion that, from a theoretical point of view, there are psychoanalyses that go on indefinitely (Freud, 1952)(11). The aim of psychoanalysis is not only to help the patient solve a specific problem, but also to put into action the resources on the basis of which he/she will be able to cope with any emotional problems. Once IN is achieved, the patient becomes able to cope with life problems.

Psychoanalysts believe that this process is possible after the patient has become aware of and understands their own problems and reactions.

A study by Obendorf(19) (1950) and another study by Lorand(18) (1963) show that psychoanalysis has succeeded in the following contexts:

-

The patient acquires the ability to accept his/her own sexuality.

-

Better social adjustment is achieved.

-

Gain an understanding of the mechanisms behind its current difficulties.

-

It reduces the tendency to become anxious, to regressive behavior, to avoid reality.

-

When a positive attitude of tolerance and acceptance of others is developed.

-

The disappearance of childhood amnesia is considered by some as an indicator of the success of the cure. If the patient still retains amnesia relating to the first five years of life, the analysis is not complete.

-

The therapeutic relationship that has been operative during the therapeutic cure must disappear. As long as the patient still has an infantile relationship, the analyzed patient remains emotionally infantile.

In On Learning from the Patient (Casement, 1985)(4), the author points out the following.

There are several ways for the patient to remember things:

-

Habitual recall carried out at a conscious level.

-

Recall that reveals unconscious content. It is characterized by a vivid image, full of ideas that seem to be relived in the present. As a rule, this content does not refer to pleasant events, but to psychological traumas, which generate anxiety and are the result of incipient searches and attempts to control previously uncontrolled anxieties.

No one has regular access to their own unconscious without the help of another person. If the unconscious contents can be interpreted tolerably but also with meaning for the patient, the repressed contents can be brought back into the conscious field.

As a rule, the therapist tries to decipher the patient’s unconscious contents. It is ignored that the patient also sometimes reads, willingly or unwillingly, in the unconscious, which means that it no longer appears as a blank screen as Freud intended.

The therapist tries not to make mistakes or fall into the trap of defensive behaviors. But this happens frequently and the patient takes advantage of these mistakes, giving a new turn to the analysis process. If the therapist learns from the patient, a positive turn can be given to the mistakes made.

The therapist has to tolerate long periods when the patient feels ignored and helpless, which leads to anxiety. The experienced therapist must behave appropriately in this situation to remain open to information that may arise.

Theory must serve the therapeutic process, not subjugate it. If the therapist can tolerate the anxiety of not being competent, and if he/she can wait until something significant emerges, the success of the therapy is assured, and the risk of projecting his/her own fears onto the patient is avoided. If a prefabricated theory is applied immediately, the therapist may become deaf to unexpected information.

When the therapist encounters elements of unconscious communication, he or she comes into contact with the process of primary genesis – the logic of the unconscious. Initially, relationships are considered to be symmetrical, the part is confronted with the whole, the outside and inside are approached identically, and the concepts of negation, contradiction and time do not operate. At the unconscious level, there can also be confusion between the experience of self and other.

By reacting to the objective elements of the similarity relation, the patient also reacts to how he/she perceives external reality in terms of affectivity. A patient may become aware of his or her dependence on the therapist. This dependence may evoke a set of other reactions involving dependence, and this explains why a break in the advanced analytic process is harder for the patient to tolerate than a long break at the beginning of the analysis.

The re-living of the past is not always linked to the therapist-patient relationship.

The therapist is trained to control his/her countertransference reactions. However, many patients fall victim to these reactions. The therapist tends to have a prefabricated attitude to what is experienced during the analysis. He/she may have a sense of false recognition between the current clinical situation and the one he/she has previously experienced.

Refocusing the analysis sessions. Sometimes, during a session, the therapists have to give the impression that they know, although they don’t. Often, it is the patient who will produce the additional material that is needed to decipher the unconscious content that had previously remained hidden.

As a rule, if the patient refuses, most analytic therapists see this as evidence of acting out resistance. It should not be forgotten that the therapist can also make mistakes and he/she must let him/herself be helped by the patient. Therefore, the therapist does not impose his/her own ideas on the patient by force. He/she must be free from the desire to heal and influence when the patient refuses an interpretation or accepts it. Formally, there may be no resistance, the therapist not noticing something wrong, manifesting his/her own resistance.

In order to protect him/herself from distorted products, from the excess of theoretical interpretations, the therapist must constantly ask him/herself questions: Is the patient’s individuality respected? Is the patient ignored or is there an attempt to forcibly manipulate him/her? Who and what content do they bring to the analytical process and why?

The therapist must remain open to what the patient communicates.

Dynamically oriented psychotherapy

The current directions of development of dynamically oriented psychotherapy are marked by the orientation of an increasing number of specialists towards short-term dynamic therapies. The average number of sessions in such a therapeutic approach is 25.

According to Strupp(25) (1977), a number of trends are emerging in the field of dynamic therapies, as follows:

-

Increasing interest in therapeutic approaches to mental disorders in young children. Therapy deals in particular with the consequences of emotional and other deficits related to the mother-child relationship. Addressing conflict, taking into account its source, is no longer seen as a universal foundation. When it does occur, it is seen as a post-effect of an early psychotrauma – a trauma that the child has not been able to overcome. This approach only makes the task of psychotherapy more difficult.

-

Shifting the focus from the treatment of classical neurotic disorders, which Freud considered the specific field of psychotherapy: anxieties, hysteria, phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorders, to more complex disorders such as psychopathies, borderline personality disorder or narcissistic disorders. Although many of these patients can benefit to some extent from psychotherapy, the therapist’s task is not an easy one.

-

Due to the integration of concepts and techniques specific to interpersonal issues into classical psychoanalysis, there is an emphasis on what specialists call the dyadic character of the psychotherapeutic relationship, which implies a re-dimensioning of the concepts of transference and countertransference. Thus, therapy is no longer seen as a distortion of a psychological reality, but as a complex phenomenon of communication, with patient and therapist both contributing to the smooth running of the therapy. Moreover, countertransference is no longer seen as an unfortunate accident in the course of psychotherapy, an accident to be eliminated or at least kept under control by the therapist; on the contrary, there is a growing emphasis on the idea that the therapist interacts empathically with the subject, with the role of empathically supporting the production of insight. Thus, the therapist is no longer a passive mirror, a blank screen, but becomes an empathic listener and an active partner in the therapeutic process.

-

The concept and practice of psychoanalysis have also evolved in the growing recognition of the importance of the therapist-subject relationship, a relationship that goes beyond the therapeutic framework, falling within the psychotherapeutic alliance (which is a cordial and sympathetic relationship and is far from being confronted with the austere and impersonal relationship between the patient and the classical analyst).

-

Psychopharmacology programs have made their mark especially in depression therapy, and more and more specialists believe that, here, classical psychoanalysis can be combined with pharmacotherapy, with very good results for patients. A particular feature of this approach has been the attempt by some American psychologists to gain the right to prescribe certain medicines.

-

Although classical psychotherapy was primarily an individual therapy, the benefits of psychodynamic processes in group therapy are now being seen along with the development of group, family and marital psychotherapy.

-

There is increasing pressure from healthcare specialists to develop specific means of treatment for specific disorders, classified according to DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)(2). Whereas until now, most dynamically oriented therapies considered psychiatric nosography as a Procrustean bed, emphasizing the uniqueness of each individual case, current trends tend to increasingly adopt the emphasis of this nosography and the adoption of the new style of thinking. Even in the field of dynamic therapy, therapeutic prescriptions for different nosographic entities are emerging are emerging.

-

In practice, very few psychotherapists remain orthodox in the application of a particular system, with most seeming to lean towards eclectic orientations.

Conclusions

Although modern societies postulate cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and other motivational coaching techniques, with rapid action on change at the level of thought and active implications in personality dynamics, the labor of the analytical act remains the golden vein of the Penelope’s canvas, on which a mature and independent Self is rebuilt, which will leave room for a Super-Self that will stake out its ideals and be light in relation to a “wild” Id, which wants from time to time to express itself beyond the symptom.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

-

Alexander F. Psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1954;2(4):722-733.

-

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th Ed., 2013.

-

Breuer J, Freud S. Studies in Hysteria. Washington, DC, Nervous & Mental Disease Publishing Co, 1936.

-

Casement P. On Learning from the Patient. London: Routledge, 1985.

-

Coleman JC, Butcher JN, Carson RC. Abnormal Psychology and Modern Life. Boston: Addison Wesley School, 1984.

-

Ferenczy S. Gedanken Uber Trauma. Int Ztschr Fur Psychoanalyse. 1934;20:5-18.

-

Frank JD. Therapeutic factors in psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1971;25(3):350–361

-

Frank JD. Persuasion and healing: a comparative study of psychotherapy. Oxford: Johns Hopkins Press, 1961.

-

French TM. The integration of behavior: Vol. 1. Basic postulates. University of Chicago Press, 1952.

-

Freud S. The Ego and Id. London: Hogarth, 1947.

-

Freud S. Analysis terminable and interminable. In: Collected Papers, vol. 5. London: Hogarth, 1952, pp. 316-357.

-

Freud S. The dynamics of transference. In: Strachey J (Ed. & Trans.). The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 12, pp. 97–108). London: Hogarth, 1958.

-

Harper RA. The new psychotherapies. Hoboken: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

-

Harper RA. Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy – 36 Systems. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1959.

-

Karasu TB. General principles of psychotherapy. In: Karasu TB, Bellak L (eds.). Specialized Techniques in Individual Psychotherapy, New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1980.

-

Knight RP. Evaluation of the results of psychoanalytic therapy. Amer J Psychiat. 1941;98:434–446.

-

Lazarus AA. Behavior therapy and beyond. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971.

-

Lorand S. Present trends in psychoanalytic therapy. In: Masserman JH (ed.): Current Psychiatric Therapies, vol. 3. Orlando FL: Grune & Stratton, 1963.

-

Oberndorf CP. Unsatisfactory Results of Psychoanalytic Therapy. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly. 1950;19:393-407.

-

Parloff M. Twenty-Five Years of Research in Psychotherapy. New York: Einstein, 1975.

-

Rogers C. On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

-

Rogers CR. Counseling and Psychotherapy: Newer Concepts in Practice. Boston:H oughton Mifflin, 1942.

-

Rorschach H. Psychodiagnostics: A Diagnostic Test Based on Perception (10th ed.). Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing Corp, 1998.

-

Rychlak JF. Lockean vs. Kantian theoretical models and the “cause” of therapeutic change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 1969;6(4):214–222.

-

Strupp HH, Hadley SW. A tripartite model of mental health and therapeutic outcomes: With special reference to negative effects in psychotherapy. American Psychologist. 1977;32(3):187–196.

-

Thorne FC. Principles of directive counseling and psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 1948;3:160-165.

-

Watson G. Areas of agreement in psychotherapy. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1940;10:698-709.

-

Watson AS. The conjoint psychotherapy of marriage partners. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1963;33(5):912-922.

-

Werner EE. Resilience in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;3:81–85.

-

Wittkower ED, Warnes H. Cultural aspects of psychotherapy. Psychother Psychosom. 1974;24(4-6):303-10.