Training in adult general and in child and adolescent psychiatry lasts five years in Romania. During this time, the young trainee must acquire the knowledge necessary to practice psychiatry. We have made a transversal study to determine the opinions of trainees with regards to their training. We explore in this article the possibilities available to trainee doctors with regard to education (summer schools, exchange programmes, alternative learning methods).

Necesităţile şi oportunităţile medicilor rezidenţi în psihiatrie din România

Opportunities and needs of trainees in psychiatry from Romania

First published: 16 septembrie 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.62.3.2020.3876

Abstract

Rezumat

Pregătirea în specialitatea psihiatrie, respectiv psihiatrie pediatrică, durează cinci ani în România. Pe parcursul acestei perioade, tânărul medic trebuie să îşi însuşească abilităţile necesare pentru a putea profesa ca medic specialist. Am realizat un studiu transversal printre actualii medici rezidenţi pentru a stabili dacă aceştia sunt mulţumiţi de actuala lor pregătire. Explorăm în cadrul acestui articol posibilităţile educative care le sunt disponibile rezidenţilor (şcoli de vară, programe de schimb, metode alternative de învăţământ).

Introduction

The Association of Psychiatry Trainees from Romania (AMRPR) was founded in 1996 due to Prof. Mircea Lăzărescu. The role of this association is to support and uphold the interests of trainee doctors in general adult and in child and adolescent psychiatry. AMRPR has been a member of The European Federation of Psychiatry Trainees (EFPT) since 1997. EFPT promotes trainee interests at an European level. There is an annual congress organized by AMRPR where Romanian colleagues come together and share their experiences. It is an opportunity for trainees to engage in scientific research and to give presentations in front of their peers. Through the questionnaire that we will present in the second part of this article we want to find what are the trainees’ opinions regarding their training and what sort of opportunities they have for their future careers.

One becomes a trainee doctor in Romania upon successfully passing the residency exam. Upon passing, the candidate chooses his future specialty, in this case general adult psychiatry/child and adolescent psychiatry. As it stands, the training period in Romania is five years. During this time the trainee spends his time mostly doing psychiatry rotations. But they must also do internal medicine (or paediatrics) and neurology (child and adolescent neurology) in order to acquire the necessary skills to practice psychiatry, skills which can be found in the training curricula of the two specialties(1,2). However, going through the documentations provided by the Romanian Ministry of Health we find that there is no official bibliography for general adult psychiatry. This has been brought into the forefront for many years, but it has not changed yet. Realistically, every training centre in Romania has its own curriculum. But for any given subject, one must have a benchmark to which one must always compare. This is not possible in Romania, at this time.

However, this is not specific to Romania. On the entire continent, training in psychiatry varies in time according to curricula and expertise. In Germany, training lasts five years. In the United Kingdom, it lasts six years. In France, it lasts four years. Some countries, like Germany and The Netherlands, offer psychotherapy training, while in France and Belgium it is not mandatory(3). In a continental community like the European Union it is difficult to gauge the quality of professionals if they are being trained arbitrarily. Thus, The European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) was born to foresee the training of healthcare professionals. The psychiatry section has been around since 1992. They have realised a series of guidelines which should guide trainees from the European Union(4-7). They were the first to propose an “audit” of training programmes(8). But, until now, only Germany has been subjected to such an action, without disclosing any results of the audit.

The needs of trainees

To ensure the communication between AMRPR and the population it is supposed to represent (psychiatry trainee doctors in Romania), we made a questionnaire which was distributed through social media platforms.

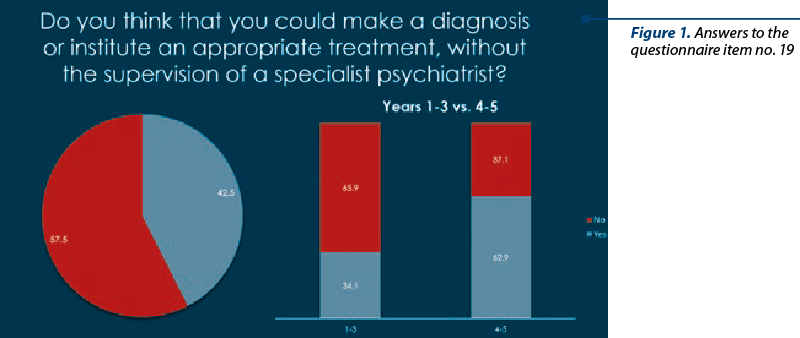

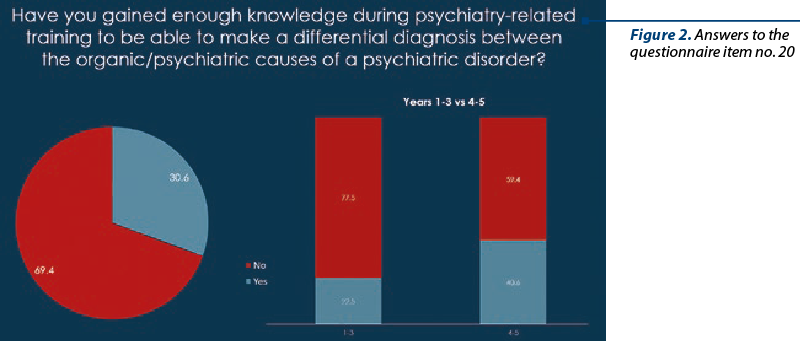

We had 120 respondents, 75% females, with a median age of 29 years old, mostly from the first three years of training in general psychiatry from Bucharest and Cluj-Napoca. We found that 80% of them would choose the same specialty again, and that 60% have opportunities to further develop their careers where they are completing their training (postgraduate courses, journal clubs, case studies etc.). However, when interacting with colleagues from abroad or from other university centres, 70% of them feel that they are underprepared professionally: 60% of the respondents do not have access to specialty literature (national and international journals), and 80% feel that they do not have the necessary conditions to acquire all the knowledge needed to practice psychiatry (Figure 1). Moreover, 71% of them accompany their attending physician when they are performing a psychiatric examination or are doing this to the relatives of the patient, 62% of them feel that their training is not in line with the national curriculum, and an overwhelming majority of 90% want a bibliography for the specialty examination which allows one to practice psychiatry on their own. Furthermore, 90% deem it necessary that one does other rotations (internal medicine/paediatrics, neurology/child and adolescent neurology etc.), however 70% feel that they do not have the necessary knowledge to institute a psychiatric treatment or to establish a psychiatric differential diagnosis (Figure 2). A rate of 94% of respondents find that bureaucracy is the main obstacle in their professional development, and 93% feel that volunteering could be helpful in their day-to-day activities. Also, 73% of the respondents are unhappy with the current conditions in hospitals, and 87.5% feel that resources provided by hospitals are insufficient. However, only 16.7% of the respondents have additional on call duties (without signing an additional contract) to compensate for the lack of personnel. Regarding appreciation, 62.5% of them feel that they are treated with respect by other members of the medical team (attending physician, nurses, auxiliary staff etc.), and 55.8% feel that bullying does not exist in the medical team.

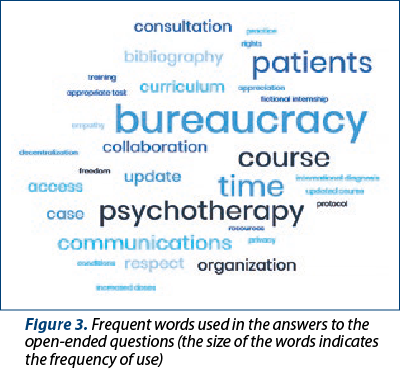

We also had open-ended questions. These are some of the answers (translated from Romanian): “Come away with bureaucracy and all other hurdles between doctor and patient”; “Weekly courses”; “A space reserved for patient evaluation, less bureaucracy for trainees”; “A bigger space, more time with patients, group discussion regarding special cases”; “Better management with regards to the number of patients being seen each day, case presentations (diagnostics, treatment, particularities) by the attending physician, less bureaucracy and specially dedicated personnel to that end”; “Social programmes, ambulatory care, psychotherapy for inpatients.”; “Rotations attuned to the curriculum, not to the needs of the clinic”; “Suport after discharge”; “Practical psychopharmachology” And we could go on for several pages.

But there is a common theme with these answers: less bureaucracy, more involvement with the patient, and the improvement of the educational act.

The study limitations are represented by the fact that we did not properly define certain terms, such as “resources”, “volunteering”, “conditions”, “bullying” and “respect”, so any conclusions that we gather are general and biased. The questions themselves were biased: the way in which they were phrased could not yield an impartial answer. The questions do not give internal validity to the questionnaire. There are several types of questions present (single choice, multiple choice, open-ended) which make the questionnaire more difficult to finish. The questions were not tested first-hand in a focus group. There was a small number of respondents compared to the number of trainees in Romania. We feel that this could be a pilot-study. AMRPR has started working on another study of this type in which it will take extra precautions not to repeat the same mistakes.

However, with all the drawbacks of this study, we can say that training in Romania is lacking: the lack of a country-wide bibliography, the perception of trainee doctors regarding their training. Some of these problems are not the fault of the trainees or of the attending physicians.

The Romanian healthcare system is taking its toll on the training of trainees. To improve the training of doctors across the country, we would make an audit (like the one proposed by UEMS). The trainee doctor should be held accountable for his own training(4-6). But with the accountability of the trainee, so should the attending be evaluated by an objective system of measurement(4-6).

Opportunities for trainees from Romania

This year we have faced an event which has not been encountered in several generations. A global pandemic has affected society on all levels. This state of affairs brings with it a bounty of new possibilities.

During this period, multimedia communication has flourished. Keeping this in mind, EFPT, The European College of Neuropsychopharmachology (ECNP), The European Psychiatry Association (EPA) etc. have organised their annual meetings in an online format(9-11). Gone are the waiting times between presentations with the quick lunch. They have been replaced by ease of access and the light of a screen. Can this be the future of medical gatherings or just a momentary adaptation to current conditions?

Organizations across Europe offer several advantages to early-career psychiatrists (defined by EPA as psychiatrists within five years of finishing their training). Besides differential fees, The European College of Neuropsychopharmachology offers free admission to trainees presenting original research. Moreover, their regularly hold summer schools of psychopharmachology are presided by renowned and esteemed professors in their fields. Their event page must be watched at all times(10). The European Psychiatry Association encourages early career psychiatrists to join their ranks. They have created a committee for early career psychiatrists which organizes regular scientific meetings(13). EPA regularly organizes summer schools of psychotherapy, an unique event in Europe and among other organizations(13).

Besides scientific opportunities, the professional organizations have understood the need of trainees and early career psychiatrists to see how psychiatry is being practiced in other corners of the world. Thus, EPA has created an observership programme, “Gaining experience programme”, that can last from 6 to 8 weeks during which an early career psychiatrist can attend psychiatric practice in a different country(12). EFPT organizes a similar programme among its member countries, but tailored toward trainees(14).

As a general recommendation for trainee doctors everywhere, professional organizations require that professionals have an online presence. This is needed in the 21st century because of the high flux of information that exists in the world and also in order to see the career opportunities that might arise. Twitter is recommended due to the brevity of posts and the ability to follow multiple entities simultaneously(15). There has been opening on the board for JAMA Psychiatry advertised on Twitter(16,17). Also, famous journals, such as Journal of Psychiatry, have special sections dedicated to early career psychiatrists(18).

Conclusions

Training for general adult and child and adolescent psychiatry in Romania does not meet the standards set by UEMS; however, the good news is that few countries in Europe truly do. With the future publication of the study being currently underway by EFPT (“Test your own training”), we shall see how each country in Europe lives up to this standard(19).

For a future when we will be able to confidently say that trainee doctors are well prepared for the professional hardships they will encounter, measures must be taken to make the trainee responsible for their own training. There are possibilities, as we have shown before. Given the current epidemiological situation, we can expect that the continuous medical education will carry on in the online arena. Which is good news for developing countries, such as Romania.

The next iteration of “The needs of the psychiatry trainee in Romania” will try to show a more realistic picture of the professional pathway of psychiatric trainees and at the same time to offer solutions.

AMRPR continues to support the decision to uphold and represent the interests of psychiatry trainees from Romania. We wish for this organization to help with the training of its members and to encourage them in all their activities. We shall continue organizing our annual congress (although we were unable to do so this year) and we wish to be more transparent in our actions in the future. We shall be organizing monthly online meetings with persons of interest for trainees in the hope that these will bring new insights on the practice of psychiatry in Romania.

Bibliografie

-

Training Curriculum in General Psychiatry. Romanian Ministry of Health. Human Resources Center in Public Health.

-

Training Curriculum in Paediatric Psychiatry. Psychiatry. Romanian Ministry of Health. Human Resources Center in Public Health.

-

Mayer S, et al. European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on post-graduate psychiatric training in Europe. European Psychiatry. 2014; 29(2):101-106.

-

Charter on training of medical specialists in the EU. European Union of Medical Specialists. Available at: https://www.uems.eu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/1415/906.pdf

-

European framework for competencies in Psychiatry. European Union of Medical Specialists. Available at: https://www.uems.eu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/43561/ETR-Psychiatry-201703.pdf

-

Profile of a psychiatrist. European Union of Medical Specialists.

-

Guidelines on psychotherapy learning experiences in psychiatry training. European Union of Medical Specialists.

-

Audit of European Training schemes in Psychiatry. European Union of Medical Specialists. Available at: http://uemspsychiatry.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/TrainingSchemeAudit-2008.pdf

-

https://www.europsy.net/

-

https://www.ecnp.eu/

-

http://efpt.eu/

-

Paglakos G, et al. What opportunities do European early career psychiatrists have? Psychiatriki. 2019 Oct;30(4):345-348.

-

http://efpt.eu/exchange/

-

https://www.europsy.net/summer-school/

-

Liu HY, et al. Social media skills for professional development in psychiatry and medicine. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2019 Sept;42(3):483-492.

-

https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/members/posts-for-members/detail/bjpsych-open-digital-content-editor

-

https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/members/posts-for-members

-

https://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/article/pages/2016/v77n05/v77n0524.aspx

-

19. http://efpt.eu/tyot/

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Lumea delirantului

Sunt prezentate 3 cazuri manifestând o simptomatologie psihotică constând în delir halucinator mistic si simptome de prim rang Schneider. Explic...

Ciudăţenii ale psihiatriei. Observaţii asupra a 50 ani de psihiatrie în România ale unui martor ocular

Această prezentare este realizată de un psihiatru care în ultimii 50 de ani a fost direct implicat în activitatea psihiatriei din România, fiind în...

Doctorul psihiatru Cicerone Postelnicu. Omul, Medicul, Legenda

The concept of integrative psychiatry and the assessment of risk factors of antisocial potential in patients with schizophrenia

Psihiatria integrativă urmăreşte asocierea la perspectiva biologică a unor factori complementari cu rol în profilaxia şi tratamentul tulburărilor m...