Primul episod psihotic la o structură de personalitate de tip schizotipal

First psychotic episode in a schizotypal personality

Abstract

According to DSM‑5 criteria, schizotypal personality disorder is characterized by social anxiety accompanied by poor interpersonal relationships, inability to maintain close relationships, bizarre behavior, suspicious character or paranoid ideation, and perceptual experiences. We present the case of a 21-year-old patient, student, without a documented psychiatric history, who presented to our clinic for a psychopathological picture that had begun about one month before: depersonalization and derealization, emotional lability, emotional ambivalence towards family members, irritability, generalized and anticipatory anxiety, flight of ideas, wear and tear, mixed insomnia, repeated statements with autolytic issues, diminished intellectual performance affecting the management of activities. During the hospitalization, the patient had an oscillating evolution, with the highlighting of obsessive and schizotypal personality traits. The two personality inventories allowed the monitoring for 6 months of the pathological psychobehavioral manifestations in which we consider the psychotic symptoms as efferents of the personality dimensions. Psychotropic, neuroleptic and mood stabilizing treatment has been shown to be useful both in fading psychotic symptoms and in normalizing personality trait levels.Keywords

schizotypalpsychosisdimensional perspectivepersonality traitsRezumat

Conform citeriilor DSM‑5, tulburarea de personalitate schizotipală, este caracterizată de anxietate socială însoţită de relaţii interpersonale deficitare, incapacitatea menţinerii unor relaţii apropiate, comportament bizar, caracter suspicios sau ideaţie paranoidă, gândire şi limbaj bizare, experienţe perceptive, credinţe bizare şi idei de referinţă. Prezentăm cazul unei paciente de 21 de ani, studentă, fără antecedente psihiatrice documentate, care se prezintă în serviciul clinicii noastre pentru un tablou psihopatologic debutat în urmă cu aproximativ o lună: fenomene de depersonalizare şi derealizare, labilitate emoţională, ambivalenţă afectivă faţă de membrii familiei, iritabilitate, anxietate generalizată şi anticipatorie, fugă de idei, logoree, insomnii mixte, afirmaţii repetate cu tematică autolitică, randament intelectual diminuat cu afectarea gestionării activităţilor. Pe parcursul internării pacienta are o evoluţie oscilantă, cu evidenţierea trăsăturilor de personalitate de tip obsesiv şi schizotipal. Cele două inventare de personalitate au permis monitorizarea timp de 6 luni a manifestărilor psihocomportamentale patologice în cadrul cărora considerăm simptomele psihotice ca eferenţe ale dimensiunilor personalităţii. Tratamentul psihotrop, neuroleptic şi stabilizator al dispoziţie s-a dovedit util atât în estomparea simptomelor psihotice, cât şi în normalizarea nivelurilor dimensiunilor personalităţii.Cuvinte Cheie

schizotipalpsihozăperspectiva dimensionalătrăsături de personalitateIntroduction

According to DSM‑5 criteria, schizotypal personality disorder is characterized by social anxiety accompanied by poor interpersonal relationships, inability to maintain close relationships, bizarre behavior, suspicious character or paranoid ideation, bizarre thinking and perceptual experiences(1). Persistent depersonalization and derealization phenomena and intermittent psychotic episodes favored by paranormal beliefs are described(2).

Schizotypal personality disorder is not sufficiently studied and is underdiagnosed. The prevalence of this disorder is estimated to be below 4%, with higher rates in men (4.2%) than in women (3.7%). The prevalence is higher among black women, in those with below average incomes and in people who have gone through a divorce or are widows. Asian men have a lower prevalence(3).

Hogan suggests that people with schizotypal personality disorder are insensitive, consider themselves special, and are immune to criticism. However, there is evidence that they are creative, innovative and insightful people(4).

Oldham and Morris argue that these people adapt and behave according to their own beliefs, whether or not others accept their worldview. They are independent and self-sufficient, requiring a minimum number of relationships due to anxiety and social phobias. They have an abstract but also speculative thinking(5).

The categorical perspective is a qualitative one limited by several factors, among which are the arbitrary nature of the number of criteria met for diagnosing a personality disorder, the high probability of comorbidity between different personality disorders, the high level of heterogeneity in diagnosis, and the increased prevalence of unspecified personality disorders(6).

However, the dimensional perspective is a quantitative one and describes the multidimensional profile of maladaptive features that contribute to the severity of the adaptive problems of the evaluated person. Through this model, the evaluator must take into account two parameters: the specific pathological features that favor the psychobehavioral manifestations, and the existence of a problem that significantly affects the social, professional and family role of the individual(7).

The level of openness is increased in schizotypal personality disorder(8), and the dimensions of extraversion and agreeableness are low. In the same context, neuroticism and introversion are increased(9).

Both perspectives aim at identifying personality disorders over a long period of time in several contexts(10).

Schizotypal personality disorder is a therapeutic challenge due to the low adherence to treatment and to the fact that in the long run there is always the inability to maintain social relationships, with low adherence to roles and impaired overall functioning(11).

Case presentation

The female patient A is 21 years old, without a personal pathological history, coming from a middle class family with two children, having a younger brother. The relationship with the family was good, with both the parents and his brother. The parents are protective people, with the mention that the father is addicted to ethanol – currently abstinent.

As a child, A describes herself as a withdrawn, shy person, without too many friends, but at the same time conscientious, with good results at school. During adolescence, she was diagnosed with nodulocystic acne, which affected her self-image, having social isolation tendencies. She has no friends and she has never had a romantic relationship.

The patient continues her studies at the Faculty of Chemistry of the Technical University of Cluj-Napoca, living alone and dedicating herself to study. During the first semester of college, she fails to make friends. She says that others do not understand her because she is different but, paradoxically, she approached her classmate without confessing her feelings, even though she planned her program according to his. During the session, due to the stress and fatigue accumulated through a poor management of rest time, there appeared states of psychomotor anxiety, emotional ambivalence, irritability, and surprisingly bizarre behavior accompanied by declarative autolytic ideation.

At the hospitalization in our clinic, she presented phenomena of depersonalization and derealization, emotional lability, emotional ambivalence towards family members, irritability, generalized anxiety, flight of ideas, mixed insomnia, repeated statements with autolytic issues, and decreased intellectual performance with impaired management activities.

The clinical picture had started about a month before, and she was administered aripiprazole, valproic acid + salts, duloxetine and alprazolam. The condition did not improve, which is why the patient was hospitalized.

The psychiatric examination outlines self and allopsychic disorientation, partially present insight, without quantitative and qualitative disturbances of perception at the time of examination. She is a hypervigilant patient, hypertensive, with selective hyperprosexia focused on education (“I have to pass all college exams”), on legality (“All things must be done legally, correctly”, “It is not normal for things to be done this way”). This is associated with selective hypermnesia focused on events considered incorrect, with flight of ideas, tachypsy, bizarre intrusive and relationship ideas, bizarre associations, suspicion, interpretativity; emotional lability with easy crying, emotional ambivalence towards family members, generalized anxiety, and irritability. In terms of behavior, hypobulia is evident, with global efficiency and low activities, pseudo-ritual behavior, and episodes of psychomotor anxiety. The patient had increased defensive instinct, mixed insomnia, low performance in the professional role, as well as episodes of depersonalization and derealization.

During the interview, she avoids eye contact, focusing on trivial details, without giving importance to the psychiatric interview, revealing obvious suspicion and interpretability.

The general clinical examination of devices and systems did not reveal pathological data and the laboratory tests indicated elevated testosterone levels.

EEG – rhythmic alpha EEG activity of 9-10 Hz, mediocre, with wide alpha spindles on bilateral temporal leads, attenuated at eye opening. In hyperpnea on bilateral temporal derivations, generally asynchronous paroxysmal discharges grouped by peaks and slow waves appear, which extend inconstantly and on parieto-occipital excuses.

The psychological examination highlighted a disharmoniously structured personality with cluster A features expressed through interpretativity, suspicion, rigid ideo-affective schemes, at hospitalization there was a flight of ideas, derealization and depersonalization phenomena, intrusive obsessive relationship ideas, emotional lability accentuated with alternation between bouts of crying and dysphoric episodes with behavioral inhibition, psychomotor anxiety, bizarre maladaptive behavior, expansive, limited emotional volume, contextual laughter, the tendency to social withdrawal (GAFS=50).

The patient’s personality was evaluated categorically and dimensionally. From a categorical point of view, the patient was administered SCID II, which revealed accentuated personality traits such as schizotypal and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

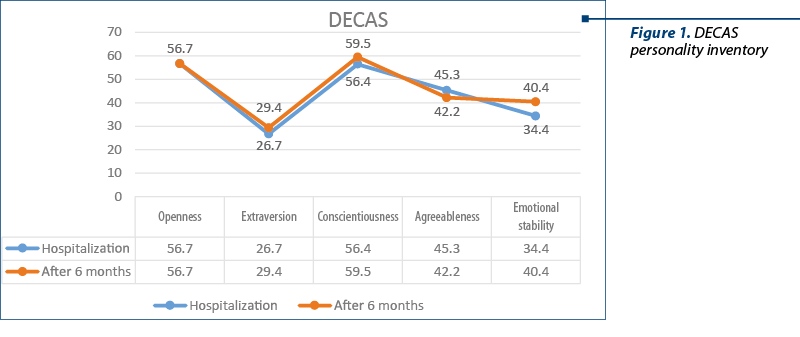

The analysis of the DECAS personality inventory (figure 1) report shows that there is no suspicion of distorting the results, and that Miss A’s personality is defined by two dominant ones: extraversion and emotional instability. There are extreme low scores on extraversion, corresponding to social withdrawal, self-closure, tendencies to loneliness, and social phobias. Emotional stability recorded low values corresponding to diffuse anxiety, irritability, impulsivity and latent aggression when personal values are violated by resorting to extreme solutions.

There were also confirmed the moderately high values of conscientiousness through the need for organization and rigor, perseverance in the actions started, the tendency of involvement developed in the role attached to educational actions, and the desire to be always in the forefront. The patient attributes herself a superior moral standard, according to which she can always appreciate the correctness-incorrectness ratio.

The low values of agreeableness are confirmed by the need for independence, ambition and competitiveness, as well as suspicion and sensitivity in relationships with others.

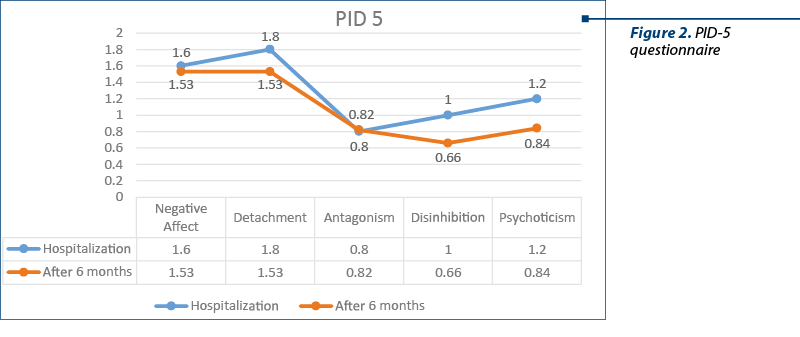

The psychological profile achieved through the PID‑5 questionnaire (figure 2) confirms a wide range of negative emotions, such as anticipatory anxiety accompanied by feelings of guilt when she fails to complete her personal plans. Anxious feelings also favor episodes of depersonalization and derealization, as well as uncertainties about the future. Increased emotional lability hypertrophies the behavioral manifestations associated with life events.

The high scores on the detachment dimension correspond to the avoidance of social interactions and the inability to form friendships. The reserved and serious quasipermanent style is obvious.

In terms of disinhibition, the values are low, confirming the spirit of fairness, perseverance, the need for self-improvement, and the accuracy of cognitive strategies.

Evolution

During the hospitalization period, the patient’s evolution was oscillating under the initial therapy with valproic acid + salts, and Imovane®. Three days after hospitalization there were delusional interpretations and bizarre behavior, for example: she starts driving cars in the yard of the institution, dissatisfied with the fact that drivers do not follow traffic rules and cars are not parked correctly, and report this incident to the police. She is careful that the other patients also follow the internal regulations; if this does not happen, she reacts aggressively. After that, risperidone is introduced into treatment, with a gradual increase in doses up to 6 mg/day. After approximately one week, the patient associated depressive symptoms, which is why sertraline 50 mg/day was introduced into the treatment. After 21 days of hospitalization and after a favorable evolution, the patient was discharged with the following treatment regimen: sertraline 50 mg/day, risperidone 6 mg/day, valproic acid + salts 500 mg/day, Imovane® 7.5 mg/day.

Discussion

The descriptive defense mechanisms are: dissociation, projection, but also intellectualization and rationalization. The intellectualization and rationalization are used to decrease social anxiety. She is also connected to obsessive tendencies and fairly obvious perfectionism. Anxiety and depersonalization episodes occur when the patient notices things that are not in line with the personal expectations, as well as with goals not properly achieved. The discourse on suicide seems to be a demonstrative one, with no correspondent in reasoning and behavioral strategies. The patient’s personality was evaluated from a dimensional point of view, using the DECAS and PID‑5 personality inventory questionnaires during hospitalization and 6 months after her discharge. During this time, the patient received treatment prescribed by the attending physician and followed psychotherapy once a week. It can be seen comparatively in the DECAS Personality Inventory that after 6 months the openness is unchanged, and that the extraversion and emotional stability have slightly increased. During these six months, Miss A’s conscientiousness increased and her agreeableness decreased.

In the evaluations with the PID‑5 questionnaire within the DSM‑5, we noticed that the values of the fields of negative affectivity, detachment, disinhibition and psychoticism decreased, except for the field of antagonism, where it registered a slight increase. The areas listed above decreased due to the improvement of depressive and psychotic symptoms. At the level of the antagonism field, the increase can be explained by the fact that our patient did not change her opinion regarding her high self-esteem, claiming to be treated preferentially because she considered herself special, smarter than others, which was also supported by her very good results obtained in college.

Conclusions

Overall, the patient became more rigorous and emotionally stable during the aforementioned period.

The two personality inventories allowed the monitoring for 6 months of the pathological psychobehavioral manifestations in which we consider the psychotic symptoms as efferents of personality dimensions, in both situations where the levels of dimensional facets are increased or decreased.

Psychotropic, neuroleptic and mood stabilizing treatment has been shown to be useful both in fading psychotic symptoms and in normalizing the personality trait levels. Wishing to restore her self-image, the patient became more compliant with the psychiatric treatment due to the obsessive component of her personality and despite she was schizotypal.

Bibliografie

-

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington 2013.

-

Lăzărescu M, Nireştean A. Tulburările de personalitate. Iaşi. Polirom. 2007.

-

Rosell DR, Futterman SE, McMaster A, Siever LJ. Schizotypal personality disorder: a current review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014; 16(7):452.

-

Hogan R, Hogan J. Hogan Development Survey Manual. Tulsa, OK: HAS. 2009.

-

Oldham J, Morris L. Personality self-portrait. New York: Bantam. 1991.

-

Gurrera R, Dickey C, Niznikiewicz M, Voglmaier M, Shenton M, McCarley R. The five-factor model in schizotypal personality disorder. Schizophrenia Research. 2006; 80, 243-51. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.002.

-

Peters ME, Taylor J, Lyketsos CG, Chisolm MS. Beyond the DSM: the perspectives of psychiatry approach to patients. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012; 14(1):PCC.11m01233. doi:10.4088/PCC.11m01233

-

Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Quigley BD, Shea M, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, et al. The representation of borderline, avoidant, obsessive-compulsive, and schizotypal personality disorders by the five-factor model. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002; 16(3), 215-234.

-

Dyce JA, O’Connor BP. Personality disorders and the five-factor model: A test of facet-level predictions. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1998; 12(1), 31-45.

-

Potuzak M, Ravichandran C, Lewandowski KE, Ongür D, Cohen BM. Categorical vs. dimensional classifications of psychotic disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2012; 53(8):1118-1129. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.04.010

-

Kirchner SK, Roeh A, Nolden J, Hasan A. Diagnosis and treatment of schizotypal personality disorder: evidence from a systematic review. NPJ Schizophr. 2018; 4(1):20. Published 2018 Oct 3. doi:10.1038/s41537-018-0062-8