Evaluarea riscului complicaţiilor materno-fetale prin utilizarea scorului de severitate a sindromului metabolic (MetS) la gravide

Risk assessment of maternal and fetal complications using the severity score of the metabolic syndrome (MetS) in pregnant women

Abstract

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is characterized by abnormal adipose tissue distribution, insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia, hypertension, chronic inflammation and procoagulant milieu. Metabolic syndrome comprises independent cardiovascular risk factors and simultaneously represents a risk factor for cardiovascular events and diabetes in the general population. In the absence of specific diagnostic criteria in pregnancy, the present study aims to analyze the role of Metabolic Syndrome Severity Score in pregnant women. The value of the MetS severity score in pregnant women in their first trimester of pregnancy can be used to predict the development of maternal and fetal complications. The MetS severity score showed an increased predictive power for the development of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, macrosomia and for the need for child admission in neonatal intensive care.Keywords

metabolic syndromepregnancyMetabolic Syndrome Severity ScoreRezumat

Sindromul metabolic (MetS) este caracterizat printr-o distribuţie anormală a ţesutului adipos, rezistenţă la insulină, dislipidemie aterogenă, hipertensiune, sindrom inflamator cronic şi printr-un teren procoagulant. Sindromul metabolic este format din factori de risc cardiovascular independenţi şi, în acelaşi timp, reprezintă factori de risc ce pot produce evenimente cardiovasculare şi diabet la populaţia generală. Din cauza absenţei unor criterii diagnostice specifice în sarcină, în acest studiu analizăm rolul Scorului de Severitate a Sindromului Metabolic la femeile gravide. Valoarea Scorului de Severitate a Sindromului Metabolic la femeia gravidă în primul trimestru de sarcină poate fi folosit pentru a prezice apariţia complicaţiilor materno-fetale. Acest scor a demonstrat o capacitate crescută de predicţie pentru apariţia diabetului gestaţional, a preeclampsiei, macrosomiei şi a necesarului internării nou-născutului în secţia de terapie intensivă neonatală.Cuvinte Cheie

sindrom metabolicsarcinăScorul de Severitate a Sindromului MetabolicIntroduction

The elements of metabolic syndrome (MetS) present in pregnant women, especially obesity, associated with the physiological immune and thrombotic changes of pregnancy, cause an increased risk of complications during pregnancy, birth and in the long term for both the mother and the fetus(1-4). The metabolic syndrome represents a group of classical cardiovascular risk factors, the association of which determines a higher risk than the isolated presence of each individual one for developing cardiovascular events and type 2 diabetes. The metabolic syndrome is associated with insulin resistance, disorders of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, proinflammatory and prothrombotic states, and with vascular and hormonal disorders(5). In terms of the operational definition, according to the consensus work of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), for females of European ethnicity, the metabolic syndrome is characterized by central obesity (waist circumference ≥80 cm) and at least two of the following criteria: triglycerides >150 mg/dl, HDL cholesterol <50 mg/dl or ongoing lipid metabolism modulating treatment, basal glycemia >100 mg/dl or diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg, or ongoing antihypertensive treatment(1,5,6).

The confirmatory factor analysis of the constituent elements of the metabolic syndrome highlighted the differential contribution and the variability of the correlation according to sex and race. This allowed the quantification of the severity of the metabolic syndrome by the Metabolic Syndrome Severity Score, a continuous score which was validated in the general population based on a representative sample from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(6,7). The score acts like a Z-score, meaning that it has a normal distribution with mean equals to 0 and standard deviation equals to 1. The formula for calculating the severity score of metabolic syndrome integrates waist circumference, logarithm of triglyceride value, serum HDL, serum glucose, and systolic blood pressure. The baseline value of the MetS severity score correlates with the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and changes in the score values in time are used to follow changes in this disease risk over time(8-10).

Objective

This study aims to analyze the differential contribution of the elements of metabolic syndrome and its severity in pregnant women using the Metabolic Syndrome Severity Score (MSSS) and its predictive ability of maternal and fetal peripartum complications.

Materials and method

Study design. This observational, retrospective study included 157 pregnant women admitted to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the “Polizu” Hospital, “Alessandrescu-Rusescu” National Institute for Mother and Child Health. The patients were considered eligible for the study if they were pregnant women in their first trimester of pregnancy and aged over 18 years old. The exclusion criteria were second-trimester or third-trimester pregnancy, aged less than 18 years old, or unwilling to participate.

The written consent of the patients and the approval of the Ethics Committee of the “Alessandrescu-Rusescu” National Institute for Mother and Child Health were obtained.

The following anthropometric data were evaluated: age, weight, height, abdominal circumference, and metabolic profile elements – systolic blood pressure, serum glucose, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol, and the presence of maternal and fetal peripartum complications.

Pregnant women included in the study were followed throughout the pregnancy by the obstetrician and those who were absent from investigations or consultations were excluded from the study.

The statistical analysis of the data was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9. Normal (Gaussian) distribution was tested using D’Agostino-Pearson test for the analyzed data. Besides tests for descriptive statistics, we used ROC curves to establish the diagnostic cut-off points for metabolic syndrome in pregnant women for the previously validated MetS severity score only in the general population and to establish diagnostic cut-off points for maternal and fetal peripartum complications.

Results

This study included patients with ages between 18 and 44 years old, admitted to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the “Polizu” Hospital – “Alessandrescu-Rusescu” National Institute for Mother and Child Health. The average age was 26.69 years old (95% CI; 25.71-27.67 years old). The average Body Mass Index in the first trimester of pregnancy was 25.05 kg/m2 (95% CI; 24.26-25.84 kg/m2).

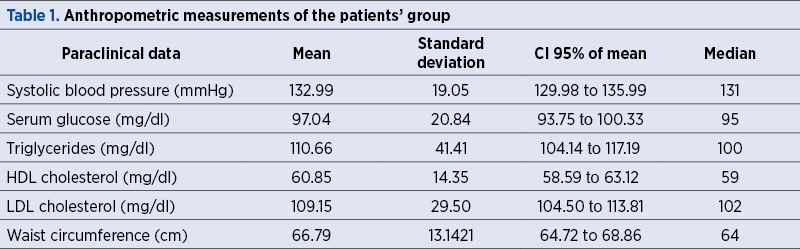

The descriptive analysis of the data describing the metabolic profile is presented in Table 1.

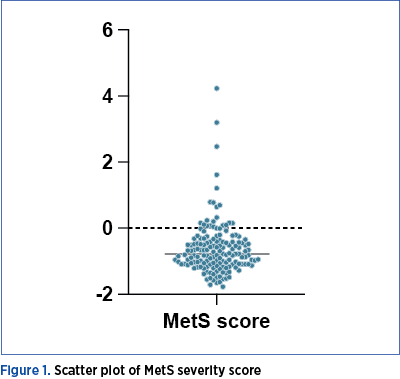

The median value of MetS severity score was -0.77 points, with a confidence interval of -0.8768 to -0.6558 and, regarding the discrepancy level, this value had an actual confidence level of 96.24% (Figure 1).

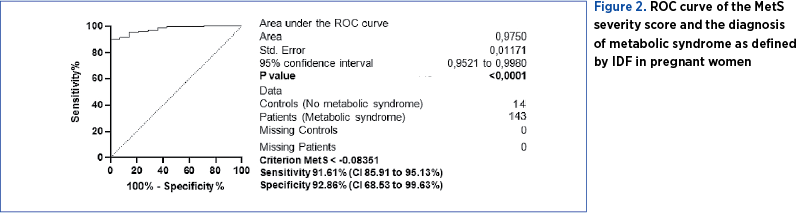

We used a ROC curve that used as dependent variable the MetS severity score and the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome (independent variable) as defined by IDF. The criterion chosen for the best sensitivity (91.61% CI; 85.91% to 95.13%) and specificity (92.86% CI; 68.53% to 99.63%) in establishing the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome was the value of -0.08351 of the MetS severity score (Figure 2).

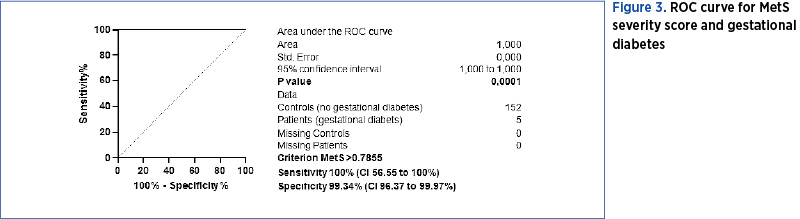

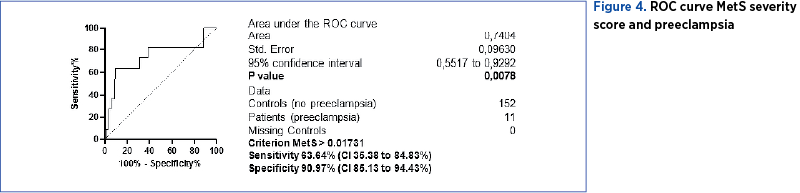

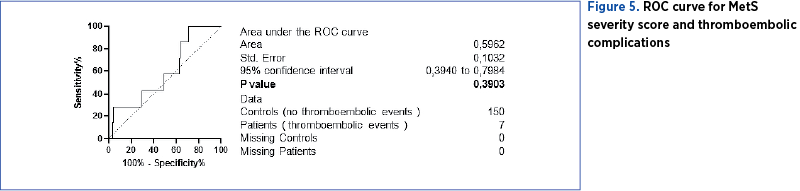

We used ROC curves that used MetS severity score and maternal complications as variables: gestational diabetes (Figure 3), preeclampsia (Figure 4), and thromboembolic events (Figure 5). We determined the cut-off point value for the best sensitivity and diagnostic specificity where the predictive ability of the data was observed. The cut-off point chosen with the best sensitivity (100%) and specificity (99.34%) to predict gestational diabetes was 0.7855 points for MetS severity score (AUC=1, p<0.0001). At a value higher than 0.017 (AUC=0.74, p=0.0078) we can predict preeclampsia with a sensitivity of 63.64% and a specificity of 90.97%. However, MSSS cannot be used to predict the risk for thromboembolic events.

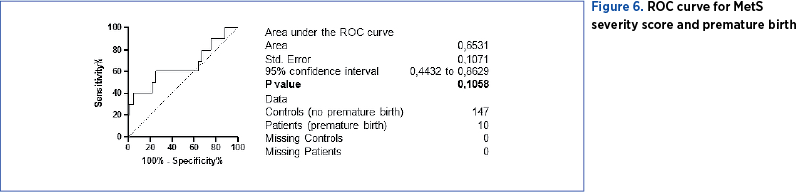

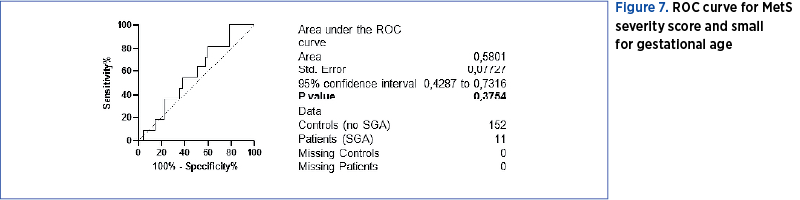

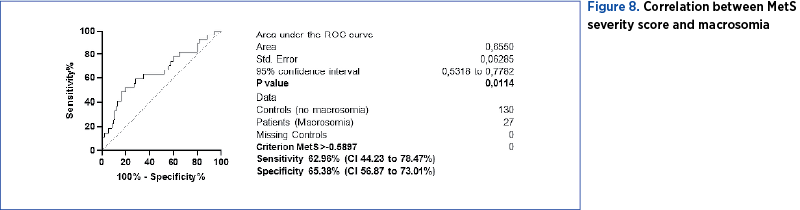

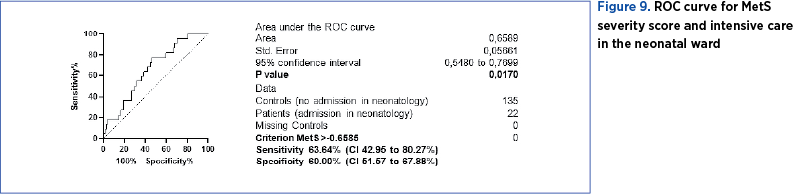

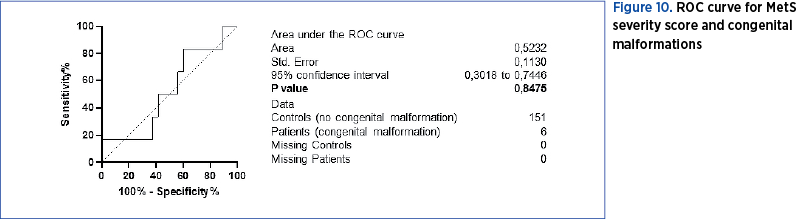

We used ROC curves that used MetS severity score as dependent variable and fetal complications as independent variables: preterm birth (Figure 6), low weight for gestational age (SGA) (Figure 7), macrosomia (Figure 8), admission and neonatal intensive care (Figure 9), and congenital malformations (Figure 10). We determined the cut-off point value for the best sensitivity and diagnostic specificity where the predictive ability of the data was observed.

MetS severity score can be used only to predict the risk of a child small for gestational age (AUC=0.65, p=0.01) with a cut-off point of -0.5897 points (sensitivity 62.96% and specificity 65.38%) and the risk of macrosomia (AUC=0.65, p=0.01) with a cut-off point of -0.6585 (sensitivity 63.64% and specificity 60%).

Discussion

The statistical analysis of the data demonstrated the applicability of the MetS severity score in the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in pregnant women. Subsequently, the MetS severity score was calculated for each patient in the study group and its predictive capacity was analyzed in the diagnosis of maternal and fetal peripartum complications. Among the maternal complications, the MetS severity score showed an increased predictive power for the development of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, macrosomia and for the need for child admission in neonatal intensive care(4,11).

The severity of metabolic syndrome as quantified by MetS severity score was associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes and the degree of increase in its severity predicted future disease in young adults(9,12). The same findings in first-trimester pregnant women provided evidence of potential clinical utility in assessing MetS severity to detect an increased risk for gestational diabetes and to follow the clinical progress over the course of the pregnancy.

The typical risk factors for gestational diabetes are increased Body Mass Index, personal history of gestational diabetes or the birth of a fetus with macrosomia, family history of diabetes, or belonging to an ethnic group with an increased incidence of diabetes(13). Diagnostic tests are often aimed only at patients in whom these risk factors are identified, some of which do not apply in cases of primiparity or preconception(9,10). The predictive ability of the MetS severity score is particularly relevant from an epidemiological perspective. When calculated in the first trimester of pregnancy, it can be used as a screening tool for metabolic syndrome in pregnant women and for assessing the patients at risk of complications who may benefit from advanced methods of diagnosis and treatment.

According to the Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Recommendation Statement, the screening for gestational diabetes should occur at 24 weeks of gestation or after that in all pregnant women without known diabetes mellitus(14). The use of continuous MetS severity scores provides a potential opportunity in determining baseline risk of future disease in women of fertile age and in pregnant women in the first trimester of pregnancy and for following changes in the risk of developing gestational diabetes over the course of the pregnancy. Following confirmative research to demonstrate efficacy, pregnant women with high values of MetS severity score could be started on specific therapies and the MetS severity score could then be used for tracking the response to treatment(15,16).

Conclusions

The MetS severity score, not previously validated in the pregnant population, correlates with the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in the study group and can be used successfully in predicting the risk of developing maternal and fetal peripartum complications, such as preeclampsia or low birth weight, and is strongly associated with the development of gestational diabetes.

Informed Consent Statement. The informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Alberti KGMM, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome – a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):469–80.

-

Gurka MJ, Lilly CL, Oliver MN, DeBoer MD. An examination of sex and racial/ethnic differences in the metabolic syndrome among adults: A confirmatory factor analysis and a resulting continuous severity score. Metabolism. 2014;63(2):218–25.

-

Armitage JA, Poston L, Taylor PD. Developmental origins of obesity and the metabolic syndrome: the role of maternal obesity. In: Korbonits M, edit. Frontiers of Hormone Research. Basel: Karger; 2008 [cited 2022 Apr 30]:73–84. https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/115355

-

Grieger JA, Bianco-Miotto T, Grzeskowiak LE, Leemaqz SY, Poston L, McCowan LM, et al. Metabolic syndrome in pregnancy and risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes: A prospective cohort of nulliparous women. PLoS Med. 2018;15(12):e1002710.

-

Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5.

-

DeBoer MD, Gurka MJ. Clinical utility of metabolic syndrome severity scores: considerations for practitioners. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2017;10:65–72.

-

DeBoer MD, Filipp SL, Gurka MJ. Use of a metabolic syndrome severity Z Score to track risk during treatment of prediabetes: An analysis of the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(11):2421–30.

-

DeBoer MD, Gurka MJ, Woo JG, Morrison JA. Severity of the metabolic syndrome as a predictor of type 2 diabetes between childhood and adulthood: the Princeton Lipid Research Cohort Study. Diabetologia. 2015;58(12):2745–52.

-

DeBoer MD, Gurka MJ, Golden SH, Musani SK, Sims M, Vishnu A, et al. Independent associations between metabolic syndrome severity and future coronary heart disease by sex and race. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(9):1204–5.

-

Poston L, Harthoorn LF, van der Beek EM. Obesity in pregnancy: Implications for the mother and lifelong health of the child. A consensus statement. Pediatr Res. 2011;69(2):175–80.

-

Gurka MJ, Filipp SL, Pearson TA, DeBoer MD. Assessing baseline and temporal changes in cardiometabolic risk using metabolic syndrome severity and common risk scores. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(16):e009754.

-

Teodorescu COD, Herdea A, Charkaoui A, Teodorescu A, Miron AI, Popa AR. Obesity and pregnancy. Maedica. 2020;15(3):318–26.

-

US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;326(6):531.

-

Alberti KGMM, Zimmet PZ, WHO Consultation. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Provisional report of a WHO Consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539–53.

-

Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, Perak AM, Carnethon MR, Kandula NR, et al. Trends in gestational diabetes at first live birth by race and ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA. 2021;326(7):660.

-

Torloni MR, Betrán AP, Horta BL, Nakamura MU, Atallah AN, Moron AF, et al. Prepregnancy BMI and the risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2009;10(2):194–203.