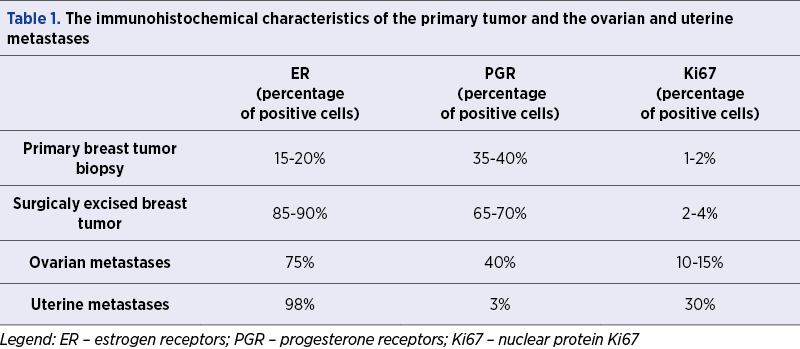

In the evolution of breast cancer, the appearance of metastases represents a decisive moment. Scientists have been trying for a long time to decipher how the metastases appear. The aim of this study is to highlight and compare the immunohistochemical characteristics of the cells from breast cancer metastases found in the uterus and ovaries. A 62-year-old patient diagnosed four years before with poorly differentiated breast ductal carcinoma arrived at the “Sf. Ioan” Emergency Clinical Hospital from Bucharest because a control computed tomography detected abnormal tumoral changes at the level of the internal genital organs. After reassessment, a hysterectomy with bilateral adnexectomy was performed. The histopathological and immunohistochemical examination of tumors found in the uterus and ovaries, which aimed to identify their nature, established that they were metastases of the ductal breast carcinoma. This situation allowed us to study comparatively their characteristics. We found significant differences: the PGR expression declined from 65-70% of cells in the primary tumor to 40% in the ovarian metastases and to 3% of cells in uterine metastases, and Ki67 expression increased from 2-4% of cells in the primary tumor to 10-15% in the ovarian metastases and up to 30% of cells in uterine metastases. These significant differences in the expression of immunohistochemical markers suggest that newly formed cell lines gain new characteristics that create advantages for them, so that they are favored in terms of dissemination, grafting and growth in a specific host organ.

Schimbări ale celulelor din metastazele unui carcinom ductal de sân dezvoltate în uter şi ovare

Changes of cells from metastases of ductal breast carcinoma developed in uterus and ovaries

First published: 20 decembrie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.69.4.2021.5780

Abstract

Rezumat

În evoluţia cancerului de sân, apariţia metastazelor reprezintă un moment decisiv. Oamenii de ştiinţă încearcă de mult timp să descifreze modul în care apar metastazele. Scopul acestui studiu este de a evidenţia şi de a compara caracteristicile imunohistochimice ale celulelor din metastazele cancerului de sân descoperite în uter şi ovare. O pacientă în vârstă de 62 de ani, diagnosticată cu patru ani înainte cu carcinom ductal mamar slab diferenţiat, a ajuns la Spitalul Clinic de Urgenţă „Sf. Ioan” din Bucureşti, deoarece la o tomografie computerizată de control s-au detectat modificări tumorale anormale la nivelul organelor genitale interne. După reevaluare, s-a efectuat histerectomie cu anexectomie bilaterală. Examenul histopatologic şi imunohistochimic al tumorilor descoperite în uter şi ovare, care a avut drept scop identificarea naturii acestora, a stabilit că sunt metastaze ale carcinomului mamar ductal. Această situaţie ne-a permis să studiem comparativ caracteristicile lor. Am găsit diferenţe semnificative: expresia PGR a scăzut de la 65-70% din celulele tumorii primare la 40% în metastazele ovariene şi la 3% din celule în metastazele uterine, iar expresia Ki67 a crescut de la 2-4% din celulele din tumora primară până la 10-15% în metastazele ovariene şi până la 30% din celule în metastazele uterine. Aceste diferenţe semnificative în expresia markerilor imunohistochimici sugerează că liniile celulare nou formate dobândesc noi caracteristici care le oferă avantaje, astfel încât ele sunt favorizate în ceea ce priveşte diseminarea, grefarea şi creşterea într-un anumit organ-gazdă.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in women in many countries of the world(1). It is well known that breast cancer, even when it represents a small mass, can metastasize and, frequently, when the tumor becomes palpable, there are already metastases(2-4). Some authors argue that breast cancer should be considered a systemic disease from the time of diagnosis(4-6).

Although the possibility of detection of metastases is technically limited, their discovery is crucial for defining the stage of the disease and for establishing the optimal treatment scheme.

Statistically, the most common sites of breast cancer metastases are the bones, brain, lungs and liver, but metastases may also occur in other places, such as the genital organs(7-9).

Because, in addition to local expansion, the occurrence and development of metastases are ones of the main factors that determine the death of the patient, scientists have been trying for a long time to decipher the mechanisms of metastasis.

“Why metastases occur in certain organs?” and “What are the conditions that must be met for their occurrence?” are the main questions. In the last decades, scientists are gathering evidence that metastasis is not a random process; there is an organ tropism with the implication of tissular mediators and also metastatic cells acquire important genetic and epigenetic new characteristics(10-12).

The purpose of this case presentation is to highlight some of the characteristics of cells from metastases in the uterus and ovaries of breast cancer.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old patient was hospitalized in the Gynecology Department of the Bucur Maternity – “Sf. Ioan” Emergency Clinical Hospital, Bucharest, for further investigations after a control computed tomography (CT) scan detected abnormal changes in myometrium and the uterine cavity.

From the patient history, we found that, four years before, she was diagnosed with a breast tumor, about 3.5 cm in diameter, located in the left breast, which infiltrated the adjacent skin. The tumor was biopsied and at the histopathological exam it was established the diagnosis of poorly differentiated breast ductal carcinoma.

At that time, immunohistochemical (IHC) exam was also performed and there were identified: estrogen receptors (ER) positive in 15-20% of cells; progesterone receptors (PGR) positive in 35-40% of cells, and the nuclear protein Ki67 positive in 1-2% of cells. The epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) were negative.

According to the initial investigations, the disease was classified in stage IIIB (T4 N2 M0). Polychemotherapy was administered for the next three months, but after this treatment, at a control CT, images suggestive of bone and lung metastases appeared. This implied the reclassification to a presumed stage IV of disease (T4a N2 M1).

Left mastectomy and axillary lymphadenectomy were performed. The histopathological examination of the tumor and of the removed lymph nodes confirmed the diagnosis of invasive breast carcinoma, ductal type, poorly differentiated, with overlying skin and nipple invasion, and metastases in axillary lymph nodes, some overcoming ganglion capsule. The postoperative staging was pT4b pN1b PMX G3. The immunohistochemical exam identified ER positive in 85-90% of cells, PGR positive in 65-70% of cells, and Ki67 positive in 2-4% of cells. HER2 was negative.

After the surgery, the patient followed six series of polychemotherapy with 270 mg of paclitaxel and 570 mg of carboplatin once every 21 days, osteoclast inhibitors treatment, using 6 mg of Bondronat® monthly for an eight-month period, and 50 mg of Bondronat® a day for the following two months; 1600 mg of Bofenos® a day for one year, and hormone therapy with an aromatase inhibitor – anastrozol 1 mg/day for three years. During the course of polychemotherapy, the patient received 500 µg of a-darbepoetinum three weeks for chemotherapy-induced anemia, and 6 MU/series of pegfilgrastim, prophylactic for leukopenia. After two years, despite the treatment, a CT scan showed that the suspicious bone foci seemed to be steadily increasing in number.

Taking into account the patient’s history, the abnormal changes in the myometrium and uterine cavity, detected by the new control tomography scan, the suspicion of uterine metastases arose. Thus, aiming a biopsy, a uterine cavity curettage was performed. The histopathological examination of collected tissue fragments identified abnormal cells arranged in stroma in small groups, nests, and rows, irregularly shaped, with quantitatively reduced eosinophilic cytoplasm, and small hyperchromic nuclei with polar localization.

Consequently, the patient underwent hysterectomy with bilateral anexectomy. The histopathological exam identified in the uterine wall and also in the ovaries metastases of breast carcinoma.

The immunohistochemical examination discovered: ovarian metastases positive for gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP15) in areas, and ER positive in 75%, PGR positive in 40%, HER2 negative, and Ki67 positive in 10-15% of the tumor cells; uterine metastases with E-cadherin negative, cytokeratin7 (CK7) positive, ER positive in 98%, PGR positive in the rare nuclei below 3%, HER2 negative, GCDFP15 positive in areas, Ki67 positive in approximately 30%, and Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1) negative in tumor cells, with smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive in smooth muscle fibers but negative in tumor cells.

After surgery, the patient underwent six series of polychemotherapy and aromataze inhibitor (letrozolum) treatment.

The clinical course was favorable and, one year after imaging examinations, bone scintigraphy and CT scan revealed no pathological evolutionary processes.

In general, breast cancer metastases in the uterus are considered rare, but as early as 1980, a study based on autopsy results (by Hagemeister et al., quoted by J.M. Debois) warns that metastases on this site have a higher incidence than was previously known (between 2% and 15% of cases)(7).

On the other hand, by searching the primary tumors in cases with metastases in the uterus, it was discovered that 43% of them were from a breast tumor(8).

The most frequent histological form of breast cancer is the ductal carcinoma, but uterine metastases, in 80% of cases, are from its lobular form, which is rarer(13).

In relation to the structure of the uterus, metastases are most frequently located in the myometrium (64% of cases), in the endometrium in only 4% of cases and, in the remaining 32% of cases, simultaneously in both the myometrium and endometrium(14).

In the presented case, CT scan raised the suspicion of uterine metastases. The biopsy by curettage could not establish with certainty the nature of the uterine tumor, due to its location in the uterine wall, even though initially it was suspected the endometrium involvement. The location in the uterine wall also explains the lack of symptoms(15).

The uterine metastases were associated with ovarian ones. Considering the higher frequency of ovarian versus uterine metastases, some researchers argued that uterine metastases originate from the ovarian metastases by lymphatic or hematogenous dissemination(9). However, the co-seeding mechanism from the primary tumor cannot be excluded.

The phenotypic differences, with regard to the immunohistochemical characteristics, between the primary tumor and the metastases, have been reported in a very few studies in the last decades(16,17). This immunohistochemical characteristics are not very well established and the reasons behind the existence of the phenotypic changes remains in the field of hypotheses.

The peculiarity of this case is that it enabled the analysis of phenotypic changes of the metastatic cells. Such cases are rare, and we can register significant immunohistochemical changes and new characteristics of cells in metastasis from ductal breast carcinoma in the uterus and ovaries (Table 1).

Analyzing the presented data, the first thing we notice is that, although the biopsy of the breast tumor was useful for the histological diagnosis, the data resulting from the immunohistochemical examination of the ER and PGR were clearly different compared to those obtained by the examination of the primary tumor. This raises questions about the usefulness of the immunohistochemical examination performed on small fragments of biopsy, in terms of guiding treatment and assessing the prognosis.

Regarding the IHC examination of the excised tumors, if the expression of ER knew no significant differences, instead there were large differences in the expression of PGR and nuclear protein Ki67. The PGR expression declined from 65-70% of cells in the primary tumor to 40% in the ovarian metastases and to 3% of cells in uterine metastases. Ki67 expression was increased from 2-4% of cells in the primary tumor to 10-15% in the ovarian metastases and up to 30% of cells in uterine metastases. Phenotypically, the registered differences signify the appearance of new cell lines, compared to those of the primary tumor, favored in terms of grafting and growth in a specific host organ.

The fact that PGR expression and the values of nuclear protein Ki67 in ovarian metastases represent an intermediary between primary tumor and uterine metastases may be another argument in favor of the hypothesis which claims that uterine metastases originate from the ovarian metastases. The frequency of this type of metastasis reported on autopsies shows that they are indicative of a distinct stage of disease progression and have important prognostic significance.

Conclusions

The occurrence of metastasis in uterus and ovaries is related to the phenotypic changes of the cells emerging from primary or secondary tumors.

The significant differences in the expression of immunohistochemical markers show that new cell lines, emerging from the primary tumor or other metastatic sites, are favored in terms dissemination, grafting and growing in a specific host organ.

The immunohistochemical examination, performed on small fragments of biopsy, in terms of guiding treatment and assessing the prognosis, can lead to a misjudgment of the case, and hence the need for this examination to be done on a sufficiently representative specimen.

In this particular case presented by us, most probably the uterine metastases originated from the ovarian metastases.

Conflicts of interests. The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest relating to or arising from this article and its content.

Consent. The written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editorial office/Chief Editor/Editorial Board members of this journal.

Ethical approval and research ethics. The “Sf. Ioan” Emergency Clinical Hospital Ethical Committee approved this case report retrospective study (Approval No. 398/17.03.2019). All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its latter amendments.

Authors’ contributions. Authors O.G. Olaru and C.V. Poalelungi managed the literature searches, designed the case presentation, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. Authors A.D. Stănescu and O.D. Bălălău provided the clinical data, and authors L. Pleş and C. M. Pena managed the analyses of the presentation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments. We thank Ariana Mihai who contributed to the tehnical review of the article.

Bibliografie

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941–1953.

- Sopik V, Narod SA. The relationship between tumor size, nodal status and distant metastases: on the origins of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;170(3):647–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4796-9.

- Abe H, Naitoh H, Umeda T, Shiomi H, Tani T, Kodama M, et al. Occult breast cancer presenting axillary limf nodal metastasis: A case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30(4):185-187.

- Jatoi I. Breast Cancer: A Systemic or Local Disease? Am J Clin Oncol. 1997;20(5):536-539.

- Redig AJ, McAllister SS. Breast cancer as a systemic disease: a view of metastasis. J Intern Med. 2013;274(2):113–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12084.

- Leone BA, Leone J, Leone JP. Breast cancer is a systemic disease rather than an anatomical process. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161:619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4104-0.

- Debois JM. TxNxM1The Anatomy and Clinics of Metastatic Cancers. Chapter 8. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 2002.

- Di Bonito L, Patriarca S, Alberico S. Breast carcinoma metastasizing to the uterus. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1985;6(3):211-217.

- Kumar NB, Hart WR. Metastases to the uterine corpus from extragenital cancers. A clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Cancer. 1982;50(10):2163–2169.

- Lu X, Kang Y. Organotropism of Breast Cancer Metastasis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12:153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-007-9047-3.

- Nathanson SD, Detmar M, Padera TP, Yates LR, Welch DR, Beadnell TC, Scheid AD, Wrenn ED, Cheung K. Mechanisms of breast cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10585-021-10090-2. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33950409.

- Liu W, Vivian CJ, Brinker AE, Hampton KR, Lianidou E, Welch DR. Microenvironmental Influences on Metastasis Suppressor Expression and Function during a Metastatic Cell’s Journey. Cancer Microenviron. 2014;7(3):117-131. doi:10.1007/s12307-014-0148-4.

- Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, Cheang MC, Voduc D, Speers CH et al. Metastatic Behavior of Breast Cancer Subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(20):3271-7.

- Arslan D, Tural D, Tatli AM, Akar E, Uysal M, Erdogan G. Isolated Uterine Metastasis of Invasive Ductal Carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:793418. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/793418.

- Piura B, Yanai-Inbar I, Rabinovich A, Zalmanov S, Goldstein J. Abnormal uterine bleeding as a presenting sign of metastases to the uterine corpus, cervix and vagina in a breast cancer patient on tamoxifen therapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;83(1):57-61.

- Haba-Rodríguez JR, Ruiz Borrego M, Gómez España A, Vilar Pastor C, Japon MA, Travado P, et al. Comparative study of the immunohistochemical phenotype in breast cancer and its lymph node metastatic location. Cancer Invest. 2004;22(2):219-24.

- Koo JS, Jung W, Jeong J. Metastatic breast cancer shows different immunohistochemical phenotype according to metastatic site. Tumori. 2010;96(3):424-32.