Pregnant women are at risk for episodes of acute respiratory failure due to anatomical changes brought on by the gestational period, as well as the characteristic immunohumoral status. Due to these changes, women are more prone to develop severe forms of respiratory pathologies and frequent complications. For this reason, pregnant women should be carefully monitored, thus avoiding dramatic situations that require mechanical ventilation, cardiorespiratory support or resuscitation maneuvers. The symptomatology and values of paraclinical parameters are often altered in pregnancy and thus they are not very helpful in diagnosis. However, early diagnosis of underlying disease is critical in these cases and the treatment should be started promptly. In addition to the idea of a careful follow-up, the presence of the fetus warrants extreme care, using some of the diagnostic and treatment techniques for maternal acute respiratory failure, as it may rapidly suffer irreversible effects due to hypoxia.

Implicaţiile obstetricale ale insuficienţei respiratorii acute în perioada peripartum

Obstetric implications of acute respiratory failure during the peripartum period

First published: 20 decembrie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.69.4.2021.5776

Abstract

Rezumat

Femeile însărcinate sunt expuse riscului de apariţie a episoadelor de insuficienţă respiratorie acută, din cauza modificărilor anatomice produse de perioada gestaţională, precum şi a statusului imunoumoral caracteristic. Din cauza acestor modificări, gravidele sunt mai predispuse să dezvolte forme severe de patologii respiratorii şi complicaţii frecvente. Din acest motiv, gravidele trebuie atent monitorizate, evitându-se astfel situaţiile dramatice care necesită ventilaţie mecanică, suport cardiorespirator sau manevre de resuscitare. Simptomatologia şi valorile parametrilor paraclinici sunt adesea modificate în sarcină şi, de aceea, nu sunt de mare ajutor în diagnostic. Cu toate acestea, diagnosticarea precoce a bolii de bază este critică în asemenea cazuri, iar tratamentul trebuie început prompt. Pe lângă ideea de urmărire atentă, prezenţa fătului necesită o atenţie extremă, utilizându-se unele dintre tehnicile de diagnostic şi tratament pentru insuficienţa respiratorie acută maternă, deoarece poate suferi rapid efecte ireversibile din cauza hipoxiei.

Introduction

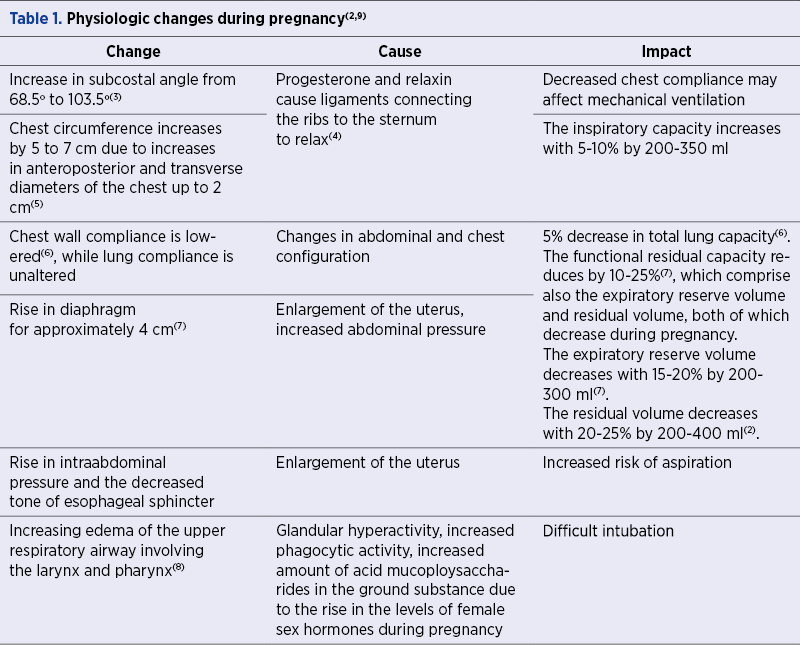

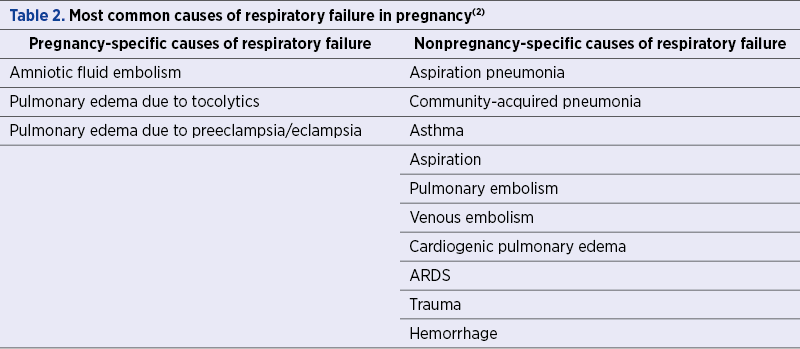

During pregnancy, the maternal respiratory tract undergoes substantial anatomic and physiologic changes which increase the susceptibility to respiratory failure. Acute respiratory failure (ARF) occurs rarely; however, it is still one of the leading conditions which mandate intensive care unit (ICU) admission in pregnancy and carries a high risk of maternal and fetal morbi-mortality(1). ARF in pregnancy can result from either obstetrics-related conditions, such as amniotic fluid embolism or severe preeclampsia, or from conditions not directly related to pregnancy, like asthma or pneumonia. As the respiratory tract undergoes multiple changes during pregnancy, these in turn will increase the risk for complications, and further tangle the overall management strategy of the pregnant woman (Table 1 and Table 2).

Causes of acute respiratory failure in pregnant women

Amniotic fluid embolism is a rare obstetric condition (1.9 to 6.1 cases per 100,000 deliveries)(10), caused by the passage of amniotic fluid or fetal debris into the maternal circulation. Maternal mortality ranges between 11% and 86%(11). Both respiratory manifestations and cardiovascular collapse, particularly when followed by disseminated intravascular coagulation, are common manifestations of this major emergency. Clinically, women experience dyspnea and hypoxia, which is initially caused by an extreme ventilation-perfusion mismatch that can further degenerate into cardiogenic pulmonary edema and shock as a result of left ventricular failure. Most frequently, amniotic fluid embolism can occur during labor, delivery or up to 30 minutes after delivery. It can also occur following a first- or second-trimester abortion, amniocentesis, miscarriage or uterine trauma(12-19). As a clinical manifestation, up to one-third of patients experience a feeling of impending doom, nausea, vomiting, chills, anxiety and agitation immediately preceding the event(13,19,20). From a fetal perspective, maternal cardiorespiratory compromise leads to a decrease in uteroplacental perfusion, with typical changes in the fetal heart rate pattern, such as late decelerations, absent baseline fetal heart rate, or terminal bradycardia(21).

The treatment in such cases should be started as soon as possible, including basic and advanced cardiac life support, hemodynamic support (fluids and vasopressors), respiratory support, the management of hemorrhage and coagulopathy and, last but not least, the delivery of the fetus if necessary(21).

In most cases, there is a major morbi-mortality after amniotic fluid embolism(13).

Pulmonary edema occurs rarely, in 0.08% of pregnancies(22), and 50% of the cases are caused by tocolytic therapy or cardiac disease, while the other 50% are due to preeclampsia or iatrogenic volume overload. Preterm labor is also an important risk factor for pulmonary edema, probably due to tocolytic therapy (usually beta-2 agonists), which is often used in these cases. Pulmonary edema is more common when women receive multiple tocolytic agents simultaneously(22,23) or if there is a coexistence of maternal infection(24). To avoid or at least to minimize the risk of complications, tocolytics should be administered in the minimal effective dose and duration. Also, in cases of preterm labor, the exposure to corticosteroid therapy increases the chance of maternal pulmonary edema(25). Fluid overload is a cause of pulmonary edema in pregnant women because there is a physiologic status of increased capillary permeability, but also because they frequently receive a large amount of intravenous fluids for hypotension caused by peripheral vasodilation(26).

The signs and symptoms of pulmonary edema include shortness of breath, tachypnea, tachycardia, hypoxemia, chest pain, basal crackles, and bilateral air space loss on chest X-ray(2) . In such situations, tocolysis should be discontinued, oxygen therapy should be supplemented, fluid restricted and generally no mechanical ventilation is needed. Most cases resolve within 12 to 24 hours. Other than tocolytics, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine and nicardipine(27-29) or magnesium sulfate(30,31) can lead to pulmonary edema. When pulmonary edema is a complication of severe preeclampsia or eclampsia, the clinical presentation is nearly identical to the one determined by amniotic fluid. These patients have dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, hypoxemia, hypertension, chest pain or cough, and diffuse crackles with bilateral air space on chest radiography. The management includes the treatment of severe preeclampsia and general management of pulmonary edema.

Pneumonia is the third cause of respiratory failure in pregnancy(32) with a high risk of complications due to the physiologic immunodeficiency and decreased functional residual capacity of the pregnant woman. The clinical symptoms are the same for both pregnant and nonpregnant women, such as dyspnea, fever, productive cough, pleural chest pain, nausea, headache, changes in mental status and myalgia.

The most common pathogens are: S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, M. pneumoniae, Legionella spp., C. pneumoniae and influenza A(33-36); however, atypical pathogens like Herpesviridae, varicella and coccidioidomycosis have been described(37,38). Usually, antibiotherapy is necessary to treat pneumonia, supported by adjunctive therapies such as supplemental oxygen and suctioning. Sometimes, mechanical ventilation is required. Pregnant women with a high risk of influenza A infection should be treated with oseltamivir starting as soon as possible(39).

Asthma is another frequent pathology in the general population, and up to 8% of pregnant women have this condition(40). One third of them have at least one exacerbation during pregnancy(41). Asthma exacerbations are most frequently met prior to 24 weeks during the second trimester. There was no medical explanation found for this fact(42,43). Intrauterine growth retardation, preterm delivery, low birth weight infants and preeclampsia are associated with maternal asthma(42). The lack in medication in these cases is usually the trigger for exacerbations. Corticoid medication is not forbidden in pregnancy, but inhaled corticosteroids should be preferred.

The harm caused by the lack of control over the exacerbations must be weighed against the effect of treatment on the product of conception, and the best option for the patient must be chosen, which is usually medication. Keep in mind that beta-agonists are as effective as corticosteroids in selected cases.

Regarding signs and symptoms, paradoxic pulse, the use of the accessory muscles for respiration, increased respiratory drive, marked hypoxemia, hyperdiaphoresis and the inability to lie supine are generally associated in asthmatic patients(44).

The management of these cases usually consists in the administration of supplemental oxygen, intravenous fluids, intravenous steroid and beta-agonist therapy. Intubation should be considered early because the combination between edematous airway physiologically present in pregnancy and bronchial over-responsiveness specific to asthmatic patients make these women difficult to intubate and ventilate(2).

Aspiration has a higher risk of occurrence in pregnant women due to the anatomical and physiologic changes like the increase of abdominal pressure, delayed gastric emptying and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Aspiration may also be a complication of general anesthesia and intubation(44). It can lead to acute bronchospasm, airway obstruction and aspiration pneumonia or chemical pneumonitis. The signs and symptoms include the rapid onset fever with productive cough, diffuse crackles in auscultation and basal infiltrates on chest films.

Usually, aspiration pneumonia is caused by anaerobic germs, therefore the treatment should be based on a penicillin derivate, such as amoxicillin or ampicillin. Ventilator support and bronchoscopy with suctioning of the aspirated material are also part of the treatment(45). In order to avoid aspiration, regional anesthesia is usually preferred, with the avoidance of general anesthesia. When general anesthesia is mandated, minimizing gastric content, the administration of H2 blockers and the use of cricoid pressure for intubation are key techniques for the airway management of a pregnant woman(2).

Pulmonary embolism risk is five to six times higher in pregnancy and it is the main reason for cardiopulmonary resuscitation(46). The frequency of this event is higher in pregnancy due to the changes of clotting factors – with the decrease of protein S and the increase of procoagulation factors (I, II, VII, VIII, IX and X), constant endothelial mircoinjuries during pregnancy and pressure by the uterus on the inferior vena cava which lead to a status of hypercoagulability and venous stasis(47).

Dyspnea, swelling, dizziness, tachycardia and chest pain are the same symptoms that appear in nonpregnant women. If right heart failure appears, hypotension and shock can be present.

Computed tomography with pulmonary angiography and echocardiography to evaluate the right ventricular function are the most reliable investigations during pregnancy in order to diagnose this pathology, after the careful history and physical examination. D-dimer values are not useful for diagnostic purposes, given their modified baseline during pregnancy(48).

As treatment, first of all, the patient needs cardiopulmonary stabilization, then anticoagulation using low-molecular-weight heparin for at least three months(49). Thrombolysis is an option, but with high mortality and morbidity for both mother and the fetus (6%)(50).

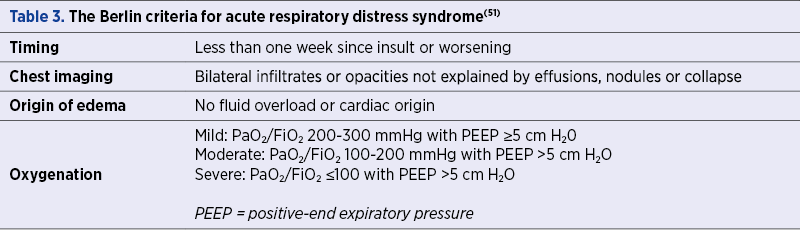

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is defined as a pathophysiologic condition of acute lung injury in which neutrophils are activated and damage of the pulmonary endothelium is present, resulting in pulmonary edema, increased shunt fraction and decreased lung compliance(32). For diagnostic purposes, the Berlin criteria (2012) are described in Table 3.

Obstetric causes of ARDS are aspiration, amniotic fluid embolism, eclampsia and preeclampsia, septic abortion, hemorrhage, tocolytic-induced pulmonary edema, while nonobstetric causes are pneumonia, transfusion, fat embolism, trauma and cardiac pulmonary edema(45).

Women usually present nonspecific symptoms like tachypnea and dyspnea, associating rales or cyanosis(52,53). The factors associated with a higher risk of death are prolonged mechanical ventilation, liver failure, renal failure requiring hemodialysis, amniotic fluid embolism, septic obstetric emboli, influenza infection and puerperal infection(44).

Maternal death is estimated between 35% to 60% of cases, and most often results from multiple organ dysfunction syndrome(54). The management in these cases includes stabilization of the patient, the identifying and treatment of the underlying condition, prevention of complications, limiting the extent of lung injury, mechanical ventilation, hemodynamic and nutritional support and the monitoring and evaluation of fetal status(55).

General measures for treatment

Because the admissions of pregnant women to the ICU are rare, there is a lack of data regarding the best approach in these cases.

The initial management is focused on oxygenation and stabilization of the patient regardless of the cause. The ongoing management includes supportive care (supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation, sedation, hemodynamic support, pain control, monitoring, volume management, nutritional support, stress ulcer prophylaxis and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis) and the treatment of the etiology(44). There is an increased risk of aspiration and mucosal edema with a decreased area of glottic opening leading to a higher chance of failed intubation, which can be avoided using more modern techniques such as fiber optic assisted intubation(56).

The prone position is also strongly recommended in extreme cases of respiratory failure like ARDS, because there is evidence showing that it improves oxygenation(57). This position is difficult for pregnant women, therefore, if the pregnancy is too advanced, lateral position in which there is a slight displacement of the uterus, that means a reduction of the compression of the vena cava, is accepted.

ECMO during pregnancy is rarely indicated, only in selected cases of refractory hypoxemia(58-61). Maternal status should be the first priority; however, the monitoring and care of the fetus, including a plan of delivery, are mandatory. There are only a few cases in which delivery of the fetus is done regardless the gestational age: abruption, severe eclampsia or preeclampsia, or maternal cardiac arrest. In all other cases, the decision is made taking into consideration three variables: the risk for the fetus if he is born, the risks for the mother due to limited diagnosis and treatment modalities, and the risk of delivery, taking into consideration the maternal status(2).

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

- Christiansen LR, Collins KA. Pregnancy-associated deaths: a 15-year retrospective study and overall review of maternal pathophysiology. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2006 Mar;27(1):11-9. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000203154.50648.33.

- Mighty HE. Acute respiratory failure in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;53(2):360-8. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181deb3f1.

- Weinberger SE, Weiss ST, Cohen WR, Weiss JW, Johnson TS. Pregnancy and the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980 Mar;121(3):559-81. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.3.559.

- Goldsmith LT, Weiss G, Steinetz BG. Relaxin and its role in pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1995 Mar;24(1):171-86.

- Contreras G, Gutiérrez M, Beroíza T, Fantín A, Oddó H, Villarroel L, Cruz E, Lisboa C. Ventilatory drive and respiratory muscle function in pregnancy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991 Oct;144(4):837-41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.837.

- Marx GF, Murthy PK, Orkin LR. Static compliance before and after vaginal delivery. Br J Anaesth. 1970 Dec;42(12):1100-4. doi: 10.1093/bja/42.12.1100.

- Hegewald MJ, Crapo RO. Respiratory physiology in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med. 2011 Mar;32(1):1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.11.001.

- Toppozada H, Michaels L, Toppozada M, El-Ghazzawi I, Talaat M, Elwany S. The human respiratory nasal mucosa in pregnancy. An electron microscopic and histochemical study. J Laryngol Otol. 1982 Jul;96(7):613-26. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100092902.

- Tan EK, Tan EL. Alterations in physiology and anatomy during pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013 Dec;27(6):791-802. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.001.

- Knight M, Berg C, Brocklehurst P, Kramer M, Lewis G, Oats J, Roberts CL, Spong C, Sullivan E, van Roosmalen J, Zwart J. Amniotic fluid embolism incidence, risk factors and outcomes: a review and recommendations. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012 Feb 10;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-7.

- McDonnell NJ, Percival V, Paech MJ. Amniotic fluid embolism: a leading cause of maternal death yet still a medical conundrum. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2013 Nov;22(4):329-36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2013.08.004.

- Kaur K, Bhardwaj M, Kumar P, Singhal S, Singh T, Hooda S. Amniotic fluid embolism. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Apr-Jun;32(2):153-9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.173356.

- Clark SL, Hankins GD, Dudley DA, Dildy GA, Porter TF. Amniotic fluid embolism: analysis of the national registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Apr;172(4 Pt 1):1158-67; discussion 1167-9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91474-9.

- Lawson HW, Atrash HK, Franks AL. Fatal pulmonary embolism during legal induced abortion in the United States from 1972 to 1985. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Apr;162(4):986-90. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91301-r.

- Hasaart TH, Essed GG. Amniotic fluid embolism after transabdominal amniocentesis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1983 Sep;16(1):25-30. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(83)90216-2.

- Ellingsen CL, Eggebø TM, Lexow K. Amniotic fluid embolism after blunt abdominal trauma. Resuscitation. 2007 Oct;75(1):180-3. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.02.010.

- Rainio J, Penttilä A. Amniotic fluid embolism as cause of death in a car accident – a case report. Forensic Sci Int. 2003 Nov 26;137(2-3):231-4. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.07.010.

- Drukker L, Sela HY, Ioscovich A, Samueloff A, Grisaru-Granovsky S. Amniotic Fluid Embolism: A Rare Complication of Second-Trimester Amniocentesis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2017;42(1):77-80. doi: 10.1159/000446983.

- Kaaniche FM, Chaari A, Zekri M, Bahloul M, Chelly H, Bouaziz M. Amniotic fluid embolism complicating medical termination of pregnancy. Can J Anaesth. 2016 Jul;63(7):871-4. English. doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0618-x.

- Morgan M. Amniotic fluid embolism. Anaesthesia. 1979 Jan;34(1):20-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1979.tb04862.x.

- Moore J, Baldisseri MR. Amniotic fluid embolism. Crit Care Med. 2005 Oct;33(10 Suppl):S279-85. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000183158.71311.28.

- Sciscione AC, Ivester T, Largoza M, Manley J, Shlossman P, Colmorgen GH. Acute pulmonary edema in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Mar;101(3):511-5. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02733-3

- Lamont RF. The pathophysiology of pulmonary oedema with the use of beta-agonists. BJOG. 2000 Apr;107(4):439-44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13259.x.

- Hatjis CG, Swain M. Systemic tocolysis for premature labor is associated with an increased incidence of pulmonary edema in the presence of maternal infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988 Sep;159(3):723-8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(88)80041-3.

- Ogunyemi D. Risk factors for acute pulmonary edema in preterm delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007 Aug;133(2):143-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.09.001.

- Pisani RJ, Rosenow EC 3rd. Pulmonary edema associated with tocolytic therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1989 May 1;110(9):714-8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-9-714.

- Kutuk MS, Ozgun MT, Uludag S, Dolanbay M, Yildirim A. Acute pulmonary failure due to pulmonary edema during tocolytic therapy with nifedipine. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013 Oct;288(4):953-4. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-2810-3.

- Vaast P, Dubreucq-Fossaert S, Houfflin-Debarge V, Provost-Helou N, Ducloy-Bouthors AS, Puech F, Subtil D. Acute pulmonary oedema during nicardipine therapy for premature labour. Report of five cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004 Mar 15;113(1):98-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.05.004.

- Abbas OM, Nassar AH, Kanj NA, Usta IM. Acute pulmonary edema during tocolytic therapy with nifedipine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Oct;195(4):e3-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.032.

- Samol JM, Lambers DS. Magnesium sulfate tocolysis and pulmonary edema: the drug or the vehicle? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;192(5):1430-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.093.

- Wilson MS, Ingersoll M, Meschter E, Bodea-Braescu AV, Edwards RK. Evaluating the side effects of treatment for preterm labor in a center that uses “high-dose” magnesium sulfate. Am J Perinatol. 2014 Sep;31(8):711-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358770.

- Collop NA, Sahn SA. Critical illness in pregnancy. An analysis of 20 patients admitted to a medical intensive care unit. Chest. 1993 May;103(5):1548-52. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.5.1548.

- Sheffield JS, Cunningham FG. Community-acquired pneumonia in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Oct;114(4):915-922. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8e76d.

- Graves CR. Pneumonia in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;53(2):329-36. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181de8a6f.

- Lapinsky SE. H1N1 novel influenza A in pregnant and immunocompromised patients. Crit Care Med. 2010 Apr;38(4 Suppl):e52-7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c85d5f.

- Brito V, Niederman MS. Pneumonia complicating pregnancy. Clin Chest Med. 2011 Mar;32(1):121-132. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.10.004.

- Harger JH, Ernest JM, Thurnau GR, Moawad A, Momirova V, Landon MB, Paul R, Miodovnik M, Dombrowski M, Sibai B, Van Dorsten P; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Risk factors and outcome of varicella-zoster virus pneumonia in pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2002 Feb 15;185(4):422-7. doi: 10.1086/338832.

- Bercovitch RS, Catanzaro A, Schwartz BS, Pappagianis D, Watts DH, Ampel NM. Coccidioidomycosis during pregnancy: a review and recommendations for management. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;53(4):363-8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir410.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women: 2011-12 influenza season, United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:758–63.

- Kwon HL, Triche EW, Belanger K, Bracken MB. The epidemiology of asthma during pregnancy: prevalence, diagnosis, and symptoms. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006 Feb;26(1):29-62. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2005.11.002.

- Tamási L, Horváth I, Bohács A, Müller V, Losonczy G, Schatz M. Asthma in pregnancy – immunological changes and clinical management. Respir Med. 2011 Feb;105(2):159-64. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.11.006.

- Murphy VE, Gibson P, Talbot PI, Clifton VL. Severe asthma exacerbations during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Nov;106(5 Pt 1):1046-54. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000185281.21716.02.

- Stenius-Aarniala BS, Hedman J, Teramo KA. Acute asthma during pregnancy. Thorax. 1996 Apr;51(4):411-4. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.4.411.

- Clardy PF, Reardon CC, Lockwood CJ, Hepner MDL. Acute respiratory failure during pregnancy and the peripartum period. UpToDate. 2012.

- Schwaiberger D, Karcz M, Menk M, Papadakos PJ, Dantoni SE. Respiratory Failure and Mechanical Ventilation in the Pregnant Patient. Crit Care Clin. 2016 Jan;32(1):85-95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2015.08.001.

- Brown HL, Hiett AK. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in pregnancy: diagnosis, complications, and management. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jun;53(2):345-59. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181deb27e.

- Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S, Veenstra DL, Prabulos AM, Vandvik PO. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(2 Suppl):e691S-e736S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2300.

- Chan WS, Chunilal S, Lee A, Crowther M, Rodger M, Ginsberg JS. A red blood cell agglutination D-dimer test to exclude deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Aug 7;147(3):165-70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-3-200708070-00005.

- Marshall AL. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Postgrad Med. 2014 Nov;126(7):25-34. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2014.11.2830.

- Turrentine MA, Braems G, Ramirez MM. Use of thrombolytics for the treatment of thromboembolic disease during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995 Jul;50(7):534-41. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199507000-00020.

- ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2526-33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669.

- Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012 Aug;122(8):2731-40. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331.

- Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 4;342(18):1334-49. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806.

- Cole DE, Taylor TL, McCullough DM, Shoff CT, Derdak S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in pregnancy. Crit Care Med. 2005 Oct;33(10 Suppl):S269-78. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000182478.14181.da.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, Osborn TM, Nunnally ME, Townsend SR, Reinhart K, Kleinpell RM, Angus DC, Deutschman CS, Machado FR, Rubenfeld GD, Webb SA, Beale RJ, Vincent JL, Moreno R; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013 Feb;41(2):580-637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af.

- Munnur U, Bandi VDP, Gropper M. Airway management and mechanical ventilation in pregnancy. In: Bourjeily G, Montella K, eds. Pulmonary Problems in Pregnancy (Respiratory Medicine). New York City: Humana Press-Springer Science, 2009.

- Pelosi P, Brazzi L, Gattinoni L. Prone position in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2002 Oct;20(4):1017-28. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00401702.

- Moore SA, Dietl CA, Coleman DM. Extracorporeal life support during pregnancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016 Apr;151(4):1154-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.12.027.

- Lankford AS, Chow JH, Jackson AM, Wallis M, Galvagno SM Jr, Malinow AM, Turan OM, Menaker JA, Crimmins SD, Rector R, Kaczorowski D, Griffith B, Kon Z, Herr D, Mazzeffi MA. Clinical Outcomes of Pregnant and Postpartum Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Patients. Anesth Analg. 2021 Mar 1;132(3):777-787. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005266.

- Naoum EE, Chalupka A, Haft J, MacEachern M, Vandeven CJM, Easter SR, Maile M, Bateman BT, Bauer ME. Extracorporeal Life Support in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Jul 7;9(13):e016072. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.016072.

- Pacheco LD, Saade GR, Hankins GDV. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) during pregnancy and postpartum. Semin Perinatol. 2018 Feb;42(1):21-25. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2017.11.005.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Managementul terapeutic al glioblastomului în timpul sarcinii: prezentare de caz subliniind caracteristicile clinice şi radiologice la diagnostic şi după intervenţie

Heterogeneous malignant cerebral tumors include the following types: anaplastic astrocytoma, glioblastoma multiforme type, gliosarcoma and analplas...

Managementul infecţiei cu SARS-CoV-2 în cazul pacientelor gravide. Cunoştinţele actuale privind COVID-19 în sarcină

SARS-CoV-2 – un nou tip de betacoronavirus ARN – infectează celulele epiteliale de la nivelul căilor respiratorii. Pacienţii cu COVID-19 manifestă ...

Tipuri actuale de naştere şi impactul lor asupra mamei şi fătului

În urma evoluţiei modalităţii de naştere, am constatat, potrivit unui studiu observaţional efectuat în clinica noastră în perioada 2017-2021, o ten...

The impact of insulin resistance on placental environment in pregnancies complicated with gestational diabetes mellitus

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a pregnancy-related disease which involves both short-term and long-term serious maternal and fetal conseque...