The authors are reviewing the epidemiology, etiology, incidence, classification, clinical presentation, diagnosis and differential diagnosis of neonatal herpes infection. Treatment indications, complication, neonatal prevention strategies, and short and long outcome are also reviewed.

Infecţia herpetică neonatală – review

Neonatal herpes infection – a review

First published: 24 decembrie 2017

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Peri.1.4.2017.1429

Abstract

Rezumat

Autorii trec în revistă epidemiologia, etiologia, incidenţa, tabloul clinic, diagnosticul şi diagnosticul diferenţial al infecţiilor herpetice neonatale. De asemenea, sunt descrise tratamentul, complicaţiile, strategiile de prevenţie şi prognosticul acestor infecţii.

Herpesvirus (HSV) belongs to a family called Herpesviridae, subfamilies a-Herpesviridae, type Symplexvirus. The structure consists in a double-stranded DNA, encased within protein cage called the capsid, which is wrapped in bilipid bylaier called the envelope. On the surface of the enveloped virus, the existing encoded glicoproteins are binding to their transmembrane receptors on the cell surface, the virus particle then fuses with the cell membrane, creating a pore through which the contents of the viral envelope enters the host cell and the viral DNA is transported to the cell nucleus. They are characterized by short replication courses, and capacity to destroy or to remain in latent stay in the infected cell(1).

Both type viruses (HSV1 and HSV2) were discovered in 1960 and they have similar structure; almost half genes are commune, so many of the viral antigenes are uniformly widespread in their structure, explaining the same epidemiology and clinical manifestation, but still the unique encoded regions specific to each type of virus play an important role in the infection specific feature. HSV1 infections prevalence in general population is 70-80%, while the prevalence of HSV2 infections is arround 17-25%(2).

Genital herpes is the most common disease with sexual transmission, with increased incidence, with new cases every year, but infected people are generally unaware they are infected(3). Progressive increase is seen in the number of genital HSV infection in the adult population of childbearing age(4). Genital herpes is produced mostly by HSV2, but also by HSV1 in 15-30% of cases. HSV1 infections is asociated with oral and ocular lesions.

In the general population, the primary infection results from the first exposure to HSV and lasts for 2-3 weeks. It is defined by the absence of antibodies to HSV1 and HSV2. Viral shedding begins two days after onset and continues until the reepithelization of lesions.

Clinically, it is recognized by painful papules, vesicles and hyperkeratotic ulceres in immunosuppressed persons, in the anogenital area; it may be accompanied by pruritis and sometimes urological and neurological complications. Often, systemic symptoms (fever, headache, fotophobia, myalgia, malaise) may appear for one to two days before lessions. After primary infection, HSV1 uptake trygemen ganglia and HSV2 sacrat ganglia by retrograde transport where they stay in latent form. The virus can replicate in sensory ganglia followed by anterograde transport through sensory nerves to mucosal and cutaneous sites where shedding continuous lesion formation.

Recurrent illness is the reactivation and resuming replication of latent virus and it lasts for 5-10 days. Reccurent infection can be subclinical or asymptomatic and unrecognized. Recurrent infection is recognized by lesions localized to a small anatomical area and fewer if any systemic findings. Up to 90% of infected people have no symptoms or signs, but are contagious during asymptomatic recurrences.

The clinical diagnosis of genital herpes is unreliable and requires laboratory exams(5). Neonatal herpes is commonly caused by HSV2, but 15-30% of cases can be attribuited to HSV1(8). The incidence of neonatal HSV disease is aproximattely 1 in 3000 deliveries(4).

Transplacentally acquired infection accounts for 5% of neonatal HSV infections. For more than 90% of neonatal HSV cases, the transmission during delivery is the most common route of infection and for the rest remains intrauterine and postpartum transmission(11,12).

Intrapartum neonate can be exposed to lesions or contaminated secretions. The predictors of transmission include location, number and duration of lesions. Postpartum exposure to HSV in an infant born to an HSV seronegative mother is at risk for developing neonatal herpes by exposure to contaminated biological products such as salivary secretions, inappropriate hygiene measures in the hospital or at home(13).

Precocious primary illness in the first 30 weeks is associated with high transmission rate up to 50% of cases. Late primary illness in late pregnancy is associated with a transmission rate of up to 25% of cases. In symptomatic recurrent genital herpes the transmission rate is less than 5% and in asymptomatic recurrent genital herpes is less than 1-3%(6). Therefore, transmission can be 10 times higher in women who acquire primary HSV late in pregnancy as opposed to recurrent disease. Fetal anomalies due to herpes infection are: microphthalmia, chorioretinitis, mycrocephaly, intracranial calcifications, subependimal cysts(7,9,10).

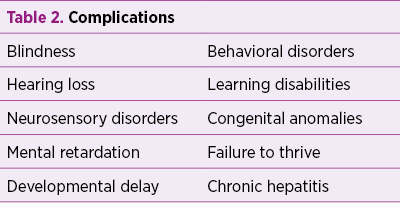

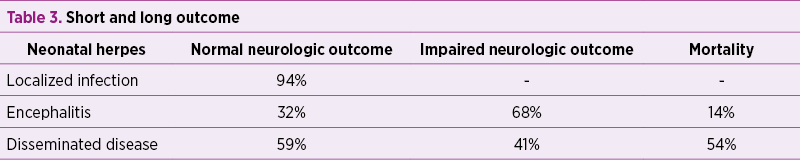

Clinical presentation - the infection begins at portal of entry or site of inoculation: traumatised skin, eyes, mouth (SEM). Infection limited to inoculation site (SEM) accounts for 45% of cases and typically presents at 7-9 days of life. In one third of cases, skin lesions are present at the illnes debut. In the severe forms, papules can develop into necrotic-hemorrhage ulcers affecting eyes - conjunctivitis, herpetic keratoconjunctivitis, mouth - gingivostomatitis and herpetic faryngitis. Vesicles may also appear on the presenting part, such as the head in a vertex presentation or the buttocks in a breech presentation, face, palms, the soles of the feet. The virus may move beyond the portal of entry, as in the neuronal spread (central nervous system disease; CNS) in 35-40% of cases, recognised by acute symptoms of meningoencephalitis - irritability, fever, bulging fontanel, opistotonus, isolated eye involvement, generalized or localized seizures, coma. Typically, it presents at 14 days of life, and sometimes at 4-6 weeks when postpartum contamination happens. Hematogenous spread - disseminated disease - typically presents in first weeks of life, being recognized by fever, necrotic-hemorrhage skin ulcers (in 50% of cases), petechiae, feeding difficulties, respiratory distress, cardiac and hepatic affections (necrotic hepatitis in 20% of cases), and disseminated intravascular coagulation disease.

Generalized or localized seizures are the most common symptom associated with herpes meningitis, and the diagnosis of herpes infection must be taken into consideration in any infant presenting with seizures with no underlying etiology(15). Ill premature infant who clinically deteriorates 1-3 weeks after delivery must be investigated for neonatal herpes(5).

The presence of a negative maternal and/or paternal history cannot reduce the level of suspicion related to neonatal herpes infection since more than 65% of pregnant women with a first genital episode are unrecognized.

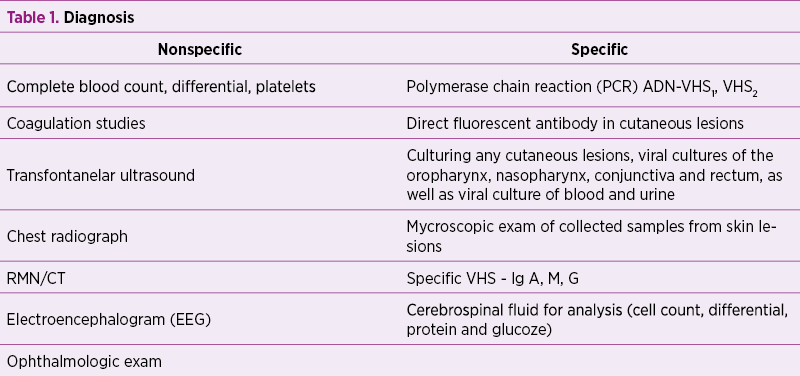

The detection of HSV DNA is extremely reliable, with a sensitivity of 75-100%, and is far superior to viral culturing of CSF. Cerebrospinal fluid for PCR and viral culture are positive in less than 50% in infants with HSV meningitis. Only 12% of infected infants will have a positive Elisa test at one week of age. About 80% of infants whose mothers experienced a herpes infection in the perinatal period were uninfected, but had positive IgG levels due to transplacental delivery of maternal antibodies. EEG may reveal either the presence of seizure activity, or an abnormal background with a paroxysmal pattern which is suggestive for HSV encephalitis. Neurologic scans show focal abnormalities in the temporal lobes, insular cortex and the gyrus rectus(17).

The diferential diagnosis must be done with bacterial infections, citomegalvirus infections, congenital syphilis, congenital rubela, varicella, and congenital candidiasis.

The treatment of neonatal herpes begings with acyclovir intravenous in SEM with 60 mg/kg c/day devided three times per day for 14 days. CNS or disseminated disease is treated with acyclovir i.v. 60 mg/kgc/day devided three times per day for 21 days. The associated complication with suppressive treatment is neutropenia, approximately 20% of patients developing an absolute neutrophil count of <1000 mcr/l. It is prudent to monitor the neutrophil counts at least twice weekly throughout the course of i.v. acyclovir therapy. If absolute count remains below 500/mcr/l for a long period, it is indicated to decrease the dose of acyclovir or to administrate granulocyte coloni-stimulating factor(24). The persons who remain PCR positive should continue antiviral therapy until PCR negativity is achieved.

Neonatal prevention strategies:

- All pregnant women should be asked about a history of genital herpes and serological screening.

- The treatment with acyclovir in pregnancy in the last four weeks of gestation. Acyclovir is free of teratogenic effects. It is concentrated in the amniotic fluid, but does not accumulate in the fetus(17).

- Caesarean delivery for women with active genital herpes. Two thirds of infected infants are delivered by women with no clinical evidence of disease or history of genital herpes. 20-30% of infants who developed neonatal herpes were delivered by caesarean section(19).

- The management of the genital herpes in the pregnant women is complex and should be individualized.

- Breastfeeding is not contraindicated unless there is a lesion on the breast.

- Appropriate hygiene measures.

As a conclusion, neonatal herpes simplex infection has high mortality and significant morbidity(14). Since the clinical symptoms associated with neonatal herpes infection are often nonspecific, the diagnosis and treatment are often delayed until the progression of the disease process occurs, with disastrous consequences. A high degree of suspicion must be present to reduce the mortality and morbidity associated with a delay in diagnosis(16).

Bibliografie

2. Ann M Gronowski. Prenatal Screening and Diagnosis of Congenital Infections. In: Handbook of Clinical Laboratory Testing During Pregnancy. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press ed. 2004.

3. Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1, global review, J Infect Dis. 2002.

4. David W. Kimberlin Neonatal Herpes Simplex Infection, Clinical microbiology reviews, Jan 2004, p. 1-13.

5. Lawrence R. Stanberry, Infection Disease and Immunologic Disorders of neonate and children, 2017.

6. Brown ZA, Benedetti J, AShley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor, Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:483-8.

7. Wagner A. Distinguishing vesicular and pustular disorders in the neonate. Curr Opin Pediatr 1997; 9:396-405.

8. Whitley RJ, Corey L, Arvin A, et al. Changing presentation of herpes simplex virus infection in neonate. J Infect Dis 1988; 158:109-16.

9. Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Selke S, et al. Asymptomatic maternal shedding of herpes simplex virus at the onset of labor: Relationship to preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87:483-8.

10. Forsgren M, Malm G. Herpes simplex virus and pregnancy. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 1996; 100:14-9.

11. Riley LE. Herpes simplex virus. Semin Perinatol 1998; 22:284-92.

12. Randolph AG, Washington AE, Prober CG. Cesarean delivery for women presenting with genital herpes lesion: Efficacy, risks, and costs. JAMA 1993; 270:77-82.

13. Fleming DT, McQuillan GM, Johnson RE, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States 1976-1994. N Engl J Med 1997; 227:1105-11.

14. Pediatrics Merck Sharp&Dohme 2017. Neonatal Herpes Virus Infection - http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/infections.

15. Kesson AM. Management of neonatal herpes simplex infection. Paediatr Drugs 2001; 3:81-90.

16. Kohl S. The diagnosis and treatment of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Ped Ann 2002; 31:726-732.

17. Leslie A. Parker, MSN, RNC, NNP; Sheryl J. Montrolwl, MSN, RNC, NNP. Neonatal Herpes Infection, a review. NAINR. 2004;4(1).

18. Anzivino E et al. Herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy and neonate: status of art of epidemiology, diagnosis, therapy and prevention. Virol J, 2009.

19. Roberts S. Herpes simplex virus incidence of neonatal herpes simplex virus, maternal screening management durin pregnancy and HIV. Obstet. Gynecol, 2009.

20. American Academy of pediatrics. Herpes simplex. In: Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseaseses, 30th ed, Kimberly DW (Ed), American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village.

21. Stanberry LR et al. Glycoprotein D - adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes, N. Engl J. Med. 2002.

22. Workowsky KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines 2015. NMWR Recomm Rep, 2015.

23. Kinberlin DW. Herpes simplex virus infections of the newborn. Semin Perinatol, 2007.

24. Kimberlin D.W., F.D. Lakeman, A.M. Arvin, C.G. Prober, L. Corey, D.A. Powell, S.K. Burchett, R. F. Jacobs, S.E. Starr, R.J. Whitley, and The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. 1996. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to the diagnosis and management of neonatal herpes simplex virus disease.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Semnificaţia gazelor din cordonul ombilical în encefalopatia nou-născutului – review al literaturii

Studii experimentale şi modele animale au arătat că encefalopatia hipoxic-ischemică este un proces în evoluţie, mai degrabă, decât un eveniment sin...

Prognosticul materno-fetal al sarcinii complicate cu ciroză biliară secundară – review al literaturii de specialitate şi prezentare de caz

Managementul gravidei cu afectare hepatică reprezintă o adevărată provocare pentru echipa complexă formată din obstetrician, gastroenterolog, neona...

Artrogripoza la un nou-născut prematur provenit din sarcină gemelară. Prezentare de caz

Artrogripoza congenitală multiplă (AMC) este caracterizată în literatura de specialitate de multiple contracturi articulare congenitale la nou-născ...

Hernie congenitală diafragmatică pe partea dreaptă - prezentare de caz

Hernia diafragmatică congenitală este o patologie ce constă în existenţa unui defect la nivelul diafragmului abdominal, din pricina căruia are loc ...