Although it is still too early and uncertain to accurately predict the outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates, the main principles guiding suicide prevention during the pandemic are that 1) suicide is preventable, 2) the time for action for mental health is now, and 3) the worldwide concerted efforts ensure a better outcome. Although a unique universal effect of pandemic on suicide is unlikely, the current data suggest that the impact will vary over time and can depend on individual socioeconomic context, ethnicity and mental health, country economic power, and global collaborations to actively promote resilience and effective response, such as the International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration.We need to address both emerging risk factors, and the potential increase of pre-pandemic risk factors for suicide. Moreover, the effective tackling of the issue requires a better understanding of the preexisting trends in suicide rates, more effective and comprehensive assessment tools, effective adjustment of previous evidence-based prevention strategies to the pandemic context, and the effective inclusion of social risk factors generating inequities in access to resources and care. Most universal strategies for suicide prevention are government-based, while selective and indicated strategies dwell on appropriate government funding of mental and social health care services; hence, the key role of policies driven by global collaborative research and spearheaded by governments in the effective tackling of suicide prevention during the pandemic. In Romania, the pandemic increased the impact of preexisting societal and community risk factors, along with barriers to appropriate family, community and professional help. Therefore, TelVerde Antisuicide emerges as an important means for suicide prevention. This resource provided by the Romanian Alliance for Suicide Prevention (a non-governmental organization) significantly improves suicide prevention on all levels, thus contributing to filling the gap created by the lack of a national, government-driven suicide prevention strategy.

Riscul de suicid în timpul pandemiei de COVID-19

Suicide risk during the COVID-19 pandemic

First published: 20 noiembrie 2020

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.63.4.2020.3954

Abstract

Rezumat

Deşi e prea devreme pentru a realiza o predicţie adecvată a efectului pandemiei de COVID-19 asupra ratei suicidului, iar situaţia este incertă, principiile de bază ce ghidează prevenţia suicidului sunt: 1) sinuciderea poate fi prevenită, 2) cel mai potrivit moment pentru a acţiona este acum şi 3) eforturile concertate la nivel global asigură o evoluţie mai favorabilă. Este puţin probabil ca pandemia să aibă un efect unic, universal asupra fenomenului suicidar, iar datele actuale sugerează că impactul pandemiei va varia în timp, depinzând de contextul socioeconomic, de etnia şi starea de sănătate mintală a fiecărui individ, respectiv de puterea economică a ţării şi de iniţiativele globale de promovare a rezilienţei şi eficienţei strategiilor, cum ar fi International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration. Este necesar să abordăm atât factorii de risc nou apăruţi, cât şi posibila accentuare a efectului factorilor de risc preexistenţi. Mai mult, abordarea eficientă a prevenţiei suicidului în timpul pandemiei necesită înţelegerea trendurilor preexistente ale ratei suicidului, dezvoltarea de instrumente de evaluare mai eficiente şi cuprinzătoare, adaptarea eficientă a strategiilor de prevenţie fundamentate ştiinţific şi deja cunoscute la contextul pandemiei, alături de includerea factorilor de risc sociali ce generează inechităţi în accesul la resurse şi îngrijiri. Majoritatea strategiilor universale de prevenţie a suicidului ţin de acţiunea statului, iar strategiile selective şi indicate au la bază finanţarea adecvată a serviciilor de sănătate mintală şi a protecţiei sociale de către instituţiile statului; de aceea, politicile guvernamentale bazate pe colaborarea globală pentru cercetare în domeniu au un rol-cheie în abordarea prevenţiei suicidului în timpul pandemiei. În România, pandemia a accentuat impactul factorilor de risc de la nivelul societăţii şi al comunităţilor, precum şi obstacolele în calea accesului la sprijin adecvat familial, comunitar şi profesional. De aceea, TelVerde Antisuicid se evidenţiază drept mijloc important de prevenţie a suicidului. Această resursă furnizată de Alianţa Română de Prevenţie a Suicidului (o organizaţie neguvernamentală) participă semnificativ la prevenţia suicidului la toate nivelurile, contribuind astfel la umplerea golului generat de lipsa unei strategii naţionale de prevenire a suicidului bazate pe un cadru instituţional.

Introduction

The sensitive topic of suicide risk during the COVID-19 pandemic entails two relevant components. Firstly, the issue of suicide risk assessment, management and prevention requires science-driven definitions and comprehensive assessment and prevention strategies flexible enough to address individual and global risks. Secondly, the COVID-19 pandemic is an ongoing medical, psychological and social global crisis, whose impact and predictability on individual suicide risk and global suicide trends are very little known, albeit extensively addressed via consistently funded research(1).

Latest developments in suicide risk assessment

The current research regarding suicide risk definition and assessment shows that a single risk factor for suicide, taken individually, is insufficient as an accurate predictor of suicide behaviour, including completed suicide(2). Furthermore, evidence of suicide risk assessment scales accuracy provides limited support for employing a specific tool in suicide risk prediction(3,4). Experts also outline the practical need for evidence-based strategies driven by more than the level of suicide risk ascertained in a single albeit comprehensive assessment, since suicide risk may widely vary accross time(5). Regardless of these caveats, suicide risk prediction can be improved through research-informed definitions of imminent suicide risk, multiple assessment tools for imminent risk, simultaneous comprehensive coverage of multiple risk factors, evidence-based timing of suicide risk assessment and wider focus on resilience and protective factors against suicide risk(6). In addition, scientific evidence supports suicide screening in primary care, as many persons who complete suicide are seen in primary care services before death(7).

The latest developments in screening for suicide are computerized assessments of persons with preexisting mental health issues, incorporating a wide range of potentially relevant factors(8), and machine learning algorhythm assessment of electronic health records, which allows a quick comprehensive testing of a large scale clinical population, combining self-reports with clinician notes, associating a wide range of specific individual factors, each with small separate contributions, but with significant enough combined contributions to predict suicide attempts and suicide, and prompt effective referral(9). More specifically, a large population study shows that machine learning can make a 3-month prediction of 43-48% of suicides and suicide attempts with 70% sensitivity and 80% specificity in primary and mental health care settings; nevertheless, these promising results need replication in clinical trials(10).

The multilevel impact of the pandemic on suicide risk and protective factors

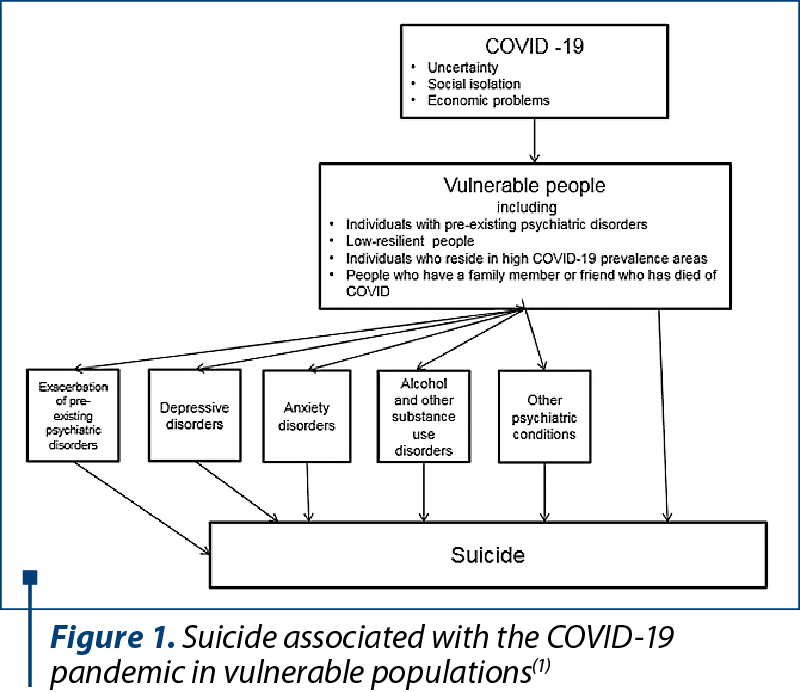

The available scientific data on suicide risk during infectious disease outbreaks of the past century (respiratory or others) are scarce, weak, of limited global relevance and of limited comparability with the nature and process of the current pandemic and the associated suicide risk(11). Multiple lines of evidence from more than 100 studies performed since the COVID-19 outbreak outline the extensive, potentially long-lasting psychological and social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in general and psychiatric population, in populations at high risk for contagion, and in COVID-19 survivors and health care staff (Figure 1). Traumatic and chronic stress, depression, fear of contagion, uncertainty, sleep problems, biopsychosocial pain, isolation, economic problems are some of the factors mediating this impact(1).

On a societal level, the pandemic enhances all risk factors through increased financial problems, pressure on health care systems, resource investment in acute pandemic response, stigma, stockpiling (including suicide means), sensationalizing of media reporting, and decreased mental health focus, activity of mental health services, help seeking, and prevention programs. Nevertheless, increased resources and government funding for health policies, telemedicine, digital tools, short-term and long-term welfare support and strengthened mental health care systems during the pandemic may enhance the protective factors against suicide on a societal level. On a community level, the pandemic is highly likely to increase the impact of suicide risk factors, such as discrimination, acculturation, dislocation, by increasing stress, decreasing effectiveness of pandemic containment measures and by deprioritization of mental health care in affected communities. However, protective factors against suicide at the community level may be enhanced by opportunities to increase resources for suicide prevention(12).

On a relationship level, risk factors such as loneliness, conflicts, loss, trauma or abuse have a greater impact during the pandemic, due to confinement, isolation, increased family abuse, loss of loved ones and to decreased access to help and supportive persons. However, more time, ways and availability to connect with relevant people during the pandemic can enhance protective factors against suicide at the relationship level. On an individual level, the pandemic increases the impact of chronic pain, drug and alcohol use, other addictive behaviours, financial problems, hopelessness and mental disorders. Also, the contribution of some individual protective factors may be limited by the pandemic, through poorer sleep, diet and physical activity, use of maladaptive coping and decreased access to religious ceremonies due to containment measures. Nevertheless, the pandemic can strengthen protective factors at an individual level through increased time to practice self-care, religion and spirituality, healthier diet, physical exercise and hobbies, and also improved sleep, daily routines, awareness of self-care and effective coping strategies – including via media and internet(12).

Adapting available evidence-based suicide prevention to the pandemic context

Based on a careful consideration of the pandemic effect on known suicide risk and protective factors, all available interventions should be strengthened during the pandemic in order to address the increased impact of risk factors for suicide. Also, new resilience-enhancing strategies and new means to deliver current ones need to be prioritized during the pandemic and sustained on a longer term, to preventively address threats, strengthen protective factors against suicide and build more resilient persons, relationships, communities and society(12).

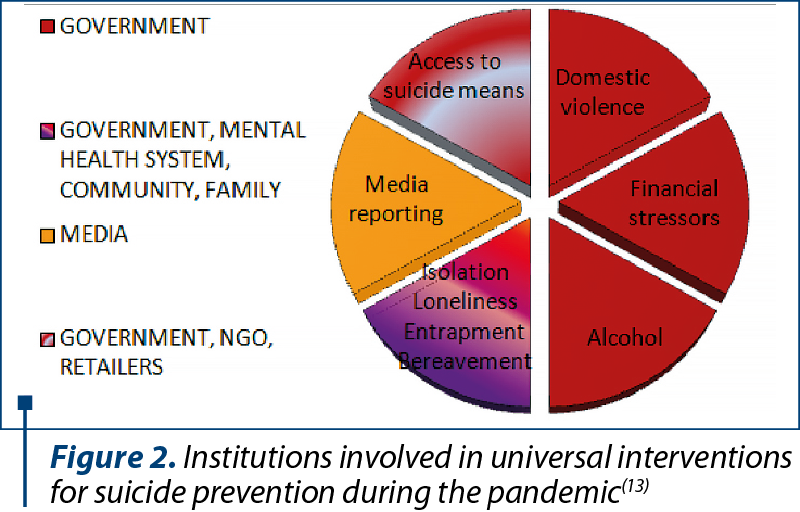

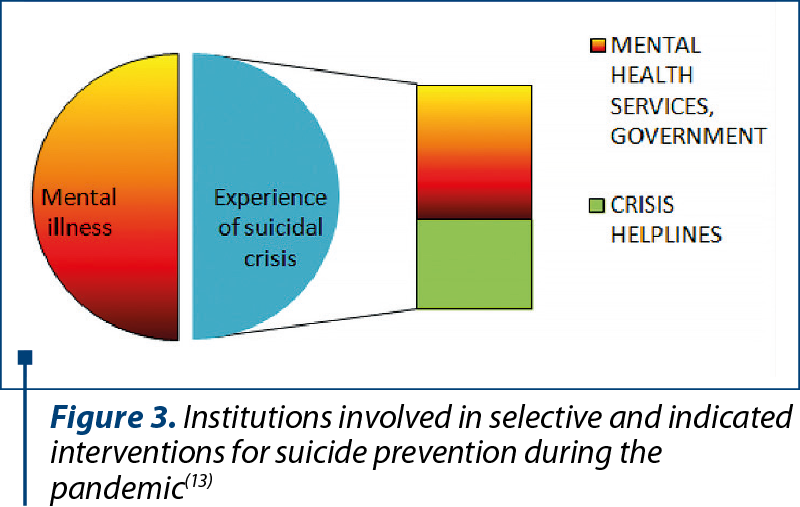

Experts provide an outline on how existing, science-driven suicide prevention measures may be tailored to fit the current pandemic context. Strengthened populational surveillance of risk factors (surveys, registries for suicidal behaviours, real-time data from crisis lines) is required in order to accurately inform measures. The universal interventions, targetting particular risk factors in the whole population, require sustained contributions of government policies, mental health services, responsible media, retailers, non-governmental organizations, communities, friends and family (Figure 2). The interventions aimed to reduce the already existing risk of suicide – selective (for persons with increased suicide risk) and indicated (for actively suicidal persons) – require an extensive contribution of mental health care services, adequate resources from governments, and crisis helplines(13) (Figure 3).

More specifically, in Romania, the national crisis helpline TelVerde Antisuicide 0800801200 of the non-governmental organization (NGO) Romanian Alliance for Suicide Prevention(14) goes beyond the aforementioned scope of selective and indicated prevention. TelVerde Antisuicide has been a significant means of universal suicide prevention since its inception on the 15th of July 2013, supporting nationwide callers regardless of their suicide risk levels. In addition to suicide crisis intervention and support for people with mental health issues or previous suicide attempts, TelVerde Antisuicide mitigates caller loneliness, isolation and entrapment, access to suicide means, impact of suicide and self-harm related (social) media reports. TelVerde Antisuicide also refers to appropriate support (mental health and social services, NGOs) for addictions, violence, abuse, bullying and financial issues.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, TelVerde Antisuicide significantly contributes to suicide prevention in Romania on all levels, by strengthening the protective factors in order to mitigate suicide, thus contributing at filling the gap of a lacking national, government-driven suicide prevention strategy. The pandemic increased the impact of preexisting societal and community risk factors, and barriers to appropriate family, community and professional help. Therefore, TelVerde Antisuicide emerged as an important means for suicide prevention. Calls to TelVerde Antisuicide during the pandemic reflect the suicide prevention efforts on all levels:

Individual – more effective life skills, coping, problem-solving, healthier lifestyle, sleep, diet and exercise, increased use of spirituality practices; decreased impact of mental health issues (including addictions), stress, pain, financial issues, hopelessness.

Relational – promoting supportive, meaningful relationships, new ways/more time to connect with the loved ones; mitigating loneliness, conflict, loss, trauma and abuse.

Community calls actively address discrimination, stigma and marginalization.

Society calls actively address barriers to care, access to means, impact of pandemic-related news, economic downturn, affected social and mental health care policies due to pandemic context and the lack of national suicide prevention policies.

TelVerde Antisuicide incorporated online tools in volunteer recruitment, training, management and assessment. Also, the volunteer training team developed in number and skills during the pandemic, in order to flexibly meet volunteer training needs. Volunteer training content also developed and adjusted in order to more effectively address pandemic-related issues: traumatic stress, existential and community crisis, fear of death and contagion, anxiety, depression, struggles with addiction and unhealthy behaviours, stigma, exclusion, violence and abuse. The role of volunteers in the community increased during the pandemic, by disseminating messages of hope, resilience, mental health promotion and accurate information about the pandemic and the available resources of support.

In the community, the positive impact of TelVerde Antisuicide during the pandemic bolsters prioritization of suicide prevention, development and funding of comprehensive, tailored and sustainable support resources, connectedness and volunteering. On a societal level, calls to TelVerde Antisuicide during the pandemic outline the need of: 1) a national, institutional approach to suicide prevention, barriers to care, economic issues, social inequities; 2) more effective funding and representation of mental health and social services.

Discussion and conclusions

Despite limitations, the current studies strongly inform on improving current strategies and creating new ones, building resilience and addressing the uncertainty of future developments(15). The suicidal behaviours are likely to significantly increase later during the pandemic, and persist for a significant period. Active, longer-term outreach on a worldwide scale via sustainable traditional and online-based strategies is warranted by current data(1). Additionally, experts ascertain that the global concerted efforts of communities, health care systems, political will, governments, clinicians and funding sources can effectively turn the threat of pandemic-related suicide risk combined with pre-pandemic risk factors into an opportunity to prioritize mental health care and signifficantly mitigate suicide risk factors on a worldwide scale(16).

Although it is still too early and uncertain to accurately predict the outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic on the suicide rates, the main principles guiding the issue are that 1) suicide is preventable; 2) the time for action for mental health is now, and 3) worldwide concerted efforts ensure a better outcome. We need to address both the emerging risk factors and the potential increase of pre-pandemic risk factors for suicide. Moreover, an effective tackling of the issue requires a better understanding of the preexisting trends in suicide rates, and the effective inclusion of social risk factors generating discrepancies in research funding, and inequalities in availability and comprehensiveness of care. The economic factors can be addressed through labour policies actively supporting access to employment. A responsible media reporting can promote mental health support. Although a unique universal effect of the pandemic on suicide is unlikely, the current data suggest that the impact will vary over time and can depend on individual socioeconomic context, ethnicity and mental health, country economic power, and global collaborations to actively promote resilience and effective response(17), such as the International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration(18).

Bibliografie

-

Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM. 2020 Oct 1;113(10):707-712.

-

Turecki G, Brent DA, Gunnell D, et al. Suicide and suicide risk. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019 Oct 24;5(1):74.

-

Runeson B, Odeberg J, Pettersson A, et al. Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: A systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 19;12(7):e0180292.

-

Barzilay S, Yaseen ZS, Hawes M, et al. Determinants and Predictive Value of Clinician Assessment of Short-Term Suicide Risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019 Apr;49(2):614-626.

-

Nielssen O, Wallace D, Large M. Pokorny’s complaint: the insoluble problem of the overwhelming number of false positives generated by suicide risk assessment. BJPsych Bull. 2017 Feb;41(1):18-20.

-

Belsher BE, Smolenski DJ, Pruitt LD, et al. Prediction Models for Suicide Attempts and Deaths: A Systematic Review and Simulation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 1;76(6):642-651.

-

Cross WF, West JC, Pisani AR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of suicide prevention training for primary care providers: a study protocol. BMC Med Educ. 2019 Feb 14;19(1):58.

-

Delgado-Gomez D, Baca-Garcia E, Aguado D, Courtet P, Lopez-Castroman J. Computerized Adaptive Test vs. decision trees: Development of a support decision system to identify suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord. 2016 Dec;206:204-209.

-

van Mens K, Elzinga E, Nielen M, et al. Applying machine learning on health record data from general practitioners to predict suicidality. Internet Interv. 2020 Aug 27;21:100337.

-

Simon GE, Johnson E, Lawrence JM, et al. Predicting Suicide Attempts and Suicide Deaths Following Outpatient Visits Using Electronic Health Records. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 1;175(10):951-960.

-

Leaune E, Samuel M, Oh H, Poulet E, Brunelin J. Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic rapid review. Prev Med. 2020 Oct 2;141:106264.

-

Wasserman D, Iosue M, Wuestefeld A, Carli V. Adaptation of evidence-based suicide prevention strategies during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020 Oct;19(3):294-306.

-

Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;7(6):468-471.

-

https://www.antisuicid.ro/blog/

-

Fitzpatrick KM, Harris C, Drawve G. How bad is it? Suicidality in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020 Jun 26;10.1111/sltb.12655.

-

Moutier C. Suicide Prevention in the COVID-19 Era: Transforming Threat Into Opportunity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020 Oct 16. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3746.

-

John A, Pirkis J, Gunnell D, Appleby L, Morrissey J. Trends in suicide during the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020 Nov 12;371:m4352.

-

International COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration. Available at: https://www.iasp.info/COVID-19_suicide_research.php.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Doctorul psihiatru Cicerone Postelnicu. Omul, Medicul, Legenda

Retrospectiva 2021 a evenimentelor ştiinţifice în domeniul psihiatriei şi sănătăţii mintale din România

Retrospectiva 2021 a evenimentelor ştiinţifice în domeniul psihiatriei şi sănătăţii mintale din România

Necesităţile şi oportunităţile medicilor rezidenţi în psihiatrie din România

The Association of Psychiatry Trainees from Romania (AMRPR) was founded in 1996 due to Prof. Mircea Lăzărescu.

Retrospectiva 2022 a evenimentelor ştiinţifice în domeniul psihiatriei şi sănătăţii mintale din România

Retrospectiva 2022 a evenimentelor ştiinţifice în domeniul psihiatriei şi sănătăţii mintale din România