Cephalhematoma is a benign condition which describes a subperiosteal hemorrhagic collection that occurs in newborns. It is caused by a prolonged birth or an instrumented assisted birth and is much more common in newborns delivered with a vacuum extractor. Although considered common, with complete resorption in most cases after 4-6 weeks, its persistence differentiates it from other pathologies. The diagnosis of this pathology is made by imaging to exclude other deeper and more severe pathologies from the cranial level. A multimodal approach to managing cephalhematoma is recommended, initiated from the earliest moments of life in order to ensure a favorable outcome. Simple cephalhematoma generally needs a noninvasive, expectant approach, while for calcified cephalhematoma, surgery is frequently required. The current general recommendations are to have an imaging examination of all newborns with cranial injury caused by birth and also that cephalhematoma cases be referred to the pediatric neurosurgery service for a more precise evaluation.

Cefalhematomul în obstetrică: o minirevizuire a unei perspective multidisciplinare

Obstetric cephalhematoma: a mini-review of a multidisciplinary perspective

First published: 28 octombrie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.69.3.2021.5558

Abstract

Rezumat

Cefalhematomul este o afecţiune benignă care descrie o colecţie hemoragică subperiosteală ce apare la nou-născuţi. Este cauzat de o naştere prelungită sau de o naştere asistată instrumentată şi este mult mai frecvent la nou-născuţii extraşi cu un vacuum-extractor. Deşi considerat banal, cu dispariţie completă în majoritatea cazurilor după 4-6 săptămâni, persistenţa acestuia orientează către alte patologii. Diagnosticul acestei patologii se face prin imagistică, pentru a exclude alte patologii mai profunde şi mai severe de la nivel cranian. Se recomandă o abordare multimodală a gestionării cefalhematomului, care ar trebui iniţiată din primele momente ale vieţii, pentru a asigura un rezultat favorabil. Cefalhematomul simplu are nevoie, în general, de o abordare neinvazivă, expectativă, în timp ce pentru cefalhematomul calcificat este frecvent necesară intervenţia chirurgicală. Recomandarea generală actuală este de a examina imagistic toţi nou-născuţii cu leziuni craniene cauzate de naştere şi, de asemenea, cazurile de cefalhematom ar trebui să fie trimise la serviciul de neurochirurgie pediatrică pentru o evaluare mai precisă.

Introduction

Scalp, skull or brain birth injuries are a series of rare complications of instrumentally assisted births due to the unevenly distributed mechanical forces, which can cause hemorrhage, edema, or rupture of cephalic structures. The most common complications are simple cephalhematoma, osteomyelitis of the skull from infected cephalhematoma, subgaleal hemorrhage and skull fracture. Intracranial injuries include extradural, subdural and subarachnoid hemorrhage, leptomeningeal cyst and brain infarction(1).

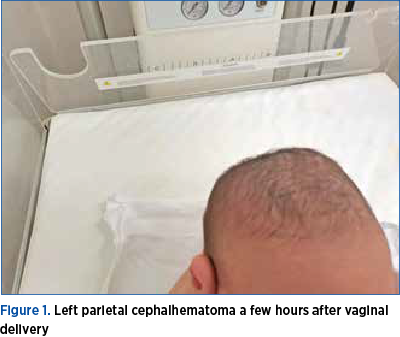

Cephalhematoma – the most common cranial injury in neonates – is a subperiosteal hemorrhagic collection that occurs in newborns, which is caused mainly through trauma at birth, but it may be seen even after a normal delivery(2) (Figure 1).

It represents a benign condition that develops during delivery, when the child’s head is subjected to excessive pressure, either due to prolonged delivery or due to the use of tools such as forceps or a vacuum extractor, which can break the blood vessels in the subperiosteal area. There are veins in the diploic space that meet between the inner and outer tables of the skull and communicate superficially with the veins of the pericranium and deeply with the meningeal veins. The rupture of the superficial communicating veins gives rise to the cephalhematoma(1). Nonetheless, cephalhematoma is not a common complication of childbirth, and only 0.2-3% of newborns develop this disease(3-5).

Cephalhematoma is defined as circumscribed, elastic and fluctuating hematoma and does not extend beyond the cranial sutures because diploic veins of each cranial bone are separated in infants(1). It is most commonly found in the parietal area and is rarely present in the occipital area. Often, cephalhematoma resolves naturally in about a month, but in cases where this process does not occur quickly enough, the hematoma calcifies. The calcification takes place concentrically, from outside to inside, which is defined as an ossification process that ultimately deforms the shape of the head.

Etiology

Cephalematoma usually occurs after a prolonged expulsion or instrumentally assisted birth(6,7).

The higher rate of the natural births in a region and the more frequent use of forceps or vacuum extractors, the higher the incidence of cephalhematoma. For example, in Germany, 6.2% of all deliveries were instrumental-assisted vaginal deliveries, 5.8% vacuum-assisted and 0.4% forceps-assisted deliveries(8). In contrast, in North America, forceps are more commonly used than video extractors(9).

This preference of the technique used influences the frequency of neonatal cephalhematoma, because it was proven that vacuum extractors have twice the rate of leading to this type of hematoma than forceps, due to the specific force distribution(10-12). A randomized controlled trial showed that metal cups are more likely to cause cephalhematoma than silastic cups or the Omnicup(13). Other more common complications when using a vacuum extractor are subarachnoid hemorrhage and brachial plexus injury(14,15).

However, some studies show that caesarean births also come with risks for both the mother and the newborn, which do not differ much in incidence and severity from instrumentally assisted births(16-19).

Calcified cephalhematoma

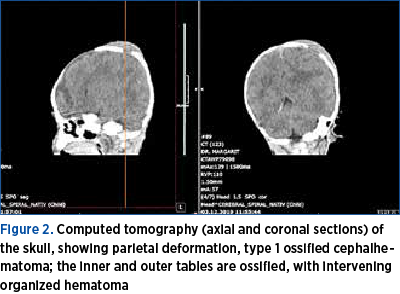

Calcified cephalhematomas are classified into two types, depending on the relationship between the contour of the inner calvary bone and the surrounding normal cranial vault. Type 1 has a nondepressed inner bone without encroachment into the cranial cavity (Figure 2), while type 2 has a depressed inner bone into the cranial cavity(20).

The most common complications of cephalhematoma are: hypotension, anemia, exostosis or jaundice. There is also a risk of primary infection through scalp microlesions, or secondary infection through bacteremia(21). Also, cephalhematoma is a risk factor for the occurrence of birth-related retinal hemorrhages secondary to the rupture of superficial retinal capillaries consecutive to the increased venous pressure(22).

Diagnosis and treatment

The diagnosis of cephalhematoma is established from the first minutes of life, by the neonatological team. To certify the diagnosis, the fetal skull is visualized using computed tomography, which helps detect the depth of the cranial injury. Following this, the diagnosis of simple cefalhematoma or calcified can be made.

In case of simple cephalhematomas, the newborn is stabilized, but no surgery is performed. The noninvasive approach is preferred, without puncture of the hematoma, but under the careful supervision of the vital functions. However, in the case of large cephalematomas, a puncture is recommended under conditions of maximum asepsis(3,23,24). In these cases, the administration of coagulation factors was also tested, especially factor XIII, with good results and a marked decrease in symptomatology(25).

Massive cephalhematomas predispose the newborn to high blood loss and severe anemia. Cases were described in the literature in which the hematocrit was 13-19%; for these newborns, in addition to aspiration of the hematoma, blood transfusions, antibiotics, phototherapy and dexamethasone are recommended(26).

Rarely, the cephalhematoma becomes infected, leading to osteomyelitis or meningitis, the diagnosis being made after the puncture(27). An infection is considered when there are a secondary enlargement of the hematoma, fluctuation, erythema, skin lesions or signs of systemic infection. In these cases, paraclinical investigations, such as inflammatory markers and imaging, have little diagnostic power. The most common causes of infected cephalhematoma are instrumental-assisted birth and sepsis, the use of scalp electrodes, skin abrasions or prolonged rupture of membranes. In these cases, the aspiration of the infectious hemorrhagic contents becomes mandatory(28).

The most common infectious pathogens are: Escherichia coli (by far, the most common pathogen isolated from infected cephalhematoma), Bacillus proteus, Gardnerella vaginalis, Escherichia hermanii, Streptococcus pneumoniae, beta-hemolytic streptococci, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Paracolobactrum coliforme, bacteroides(28).

In case of calcified cephalhematomas, the management of the newborn can take two directions: a conservative one, which follows resorption that generally occurs between 3 and 6 months of age, or the surgical excision of the ossification mass. If the second approach is chosen, it is recommended that the intervention take place as early as possible because any delay brings an enlargement of the defect and a more difficult and prolonged intervention, which often fails to return the normal shape of the skull(29-31).

Many doctors opt from the onset for surgical correction of calcified cephalhematoma for aesthetic reasons, to confirm the diagnosis and, finally, to prevent the restriction of brain growth and correct the possible associated craniosynostosis(32-34).

In conclusion, the diagnosis of cephalhematoma requires the carefully monitoring of the newborn by parents and a multidisciplinary team.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

King SJ, Boothroyd AE. Cranial trauma following birth in term infants. Br J Radiol. 1998 Feb;71(842):233-8. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.842.9579191.

-

Krishnan P, Karthigeyan M, Salunke P. Ossified Cephalhematoma: An Unusual Cause of Calvarial Mass in Infancy. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2017 Jan-Mar;12(1):64-66. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_181_16.

-

Kendall N, Woloshin H. Cephalhematoma associated with fracture of the skull. J Pediatr. 1952 Aug;41(2):125-32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(52)80047-2.

-

Uemura A, O’uchi T, Kikuchi Y. Double skull sign of ossified cephalohematoma on CT. European Journal of Radiology Extra. 2004; 49(2):35-36.

-

Wong CH, Foo CL, Seow WT. Calcified cephalohematoma: classification, indications for surgery and techniques. J Craniofac Surg. 2006 Sep;17(5):970-9. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000229552.82081.de.

-

Doumouchtsis SK, Arulkumaran S. Head injuries after instrumental vaginal deliveries. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Apr;18(2):129-34. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000192983.76976.68.

-

Doumouchtsis SK, Arulkumaran S. Head trauma after instrumental births. Clin Perinatol. 2008 Mar;35(1):69-83. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2007.11.006.

-

Statistisches Bundesamt Wiesbaden: Mehr Krankenhausentbindungen 2014 bei Gleicher Kaiserschnittrate. Mehr Krankenhausentbindungen 2014 bei Gleicher Kaiserschnittrate, 201.

-

Lomas J, Enkin M. Variations in operative delivery rates. In: Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse MJNC, editors. Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. pp. 1182–1195.

-

Weerasekera DS, Premaratne S. A randomised prospective trial of the obstetric forceps versus vacuum extraction using defined criteria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 Jul;22(4):344-5. doi: 10.1080/01443610220141227.

-

Bofill JA, Rust OA, Schorr SJ, Brown RC, Martin RW, Martin JN Jr, Morrison JC. A randomized prospective trial of the obstetric forceps versus the M-cup vacuum extractor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Nov;175(5):1325-30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70049-2.

-

Herabutya Y, O-Prasertsawat P, Boonrangsimant P. Kielland’s forceps or ventouse – a comparison. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1988 May;95(5):483-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1988.tb12801.x.

-

Attilakos G, Sibanda T, Winter C, Johnson N, Draycott T. A randomised controlled trial of a new handheld vacuum extraction device. BJOG. 2005 Nov;112(11):1510-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00729.x.

-

Wen SW, Liu S, Kramer MS, Marcoux S, Ohlsson A, Sauvé R, Liston R. Comparison of maternal and infant outcomes between vacuum extraction and forceps deliveries. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Jan 15;153(2):103-7. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.2.103.

-

Johanson RB, Rice C, Doyle M, Arthur J, Anyanwu L, Ibrahim J, Warwick A, Redman CW, O’Brien PM. A randomised prospective study comparing the new vacuum extractor policy with forceps delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993 Jun;100(6):524-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15301.x.

-

Polkowski M, Kuehnle E, Schippert C, Kundu S, Hillemanns P, Staboulidou I. Neonatal and Maternal Short-Term Outcome Parameters in Instrument-Assisted Vaginal Delivery Compared to Second Stage Cesarean Section in Labour: A Retrospective 11-Year Analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2018;83(1):90-98. doi: 10.1159/000458524.

-

Benedetto C, Marozio L, Prandi G, Roccia A, Blefari S, Fabris C. Short-term maternal and neonatal outcomes by mode of delivery. A case-controlled study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007 Nov;135(1):35-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.10.024.

-

Halscott TL, Reddy UM, Landy HJ, Ramsey PS, Iqbal SN, Huang CC, Grantz KL. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes by Attempted Mode of Operative Delivery from a Low Station in the Second Stage of Labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;126(6):1265-1272. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001156.

-

Contag SA, Clifton RG, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Varner MW, Rouse DJ, Ramin SM, Caritis SN, Peaceman AM, Sorokin Y, Sciscione A, Carpenter MW, Mercer BM, Thorp JM Jr, Malone FD, Iams JD. Neonatal outcomes and operative vaginal delivery versus cesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2010 Jun;27(6):493-9. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247605.

-

Wong CH, Foo CL, Seow WT. Calcified cephalohematoma: classification, indications for surgery and techniques. J Craniofac Surg. 2006 Sep;17(5):970-9. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000229552.82081.de.

-

Paul SP, Goodman A. Potential complications of neonatal cephalhaematoma in the community: when to refer to the paediatric team? J Fam Health Care. 2011 Jan-Feb;21(1):16-9.

-

Zhao Q, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Li Z, Lin Y, Liu R, Wei C, Ding X. Birth-related retinal hemorrhages in healthy full-term newborns and their relationship to maternal, obstetric, and neonatal risk factors. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015 Jul;253(7):1021-5. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3052-9

-

Firlik KS, Adelson PD. Large chronic cephalohematoma without calcification. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999 Jan;30(1):39-42. doi: 10.1159/000028759.

-

Tan KL. Cephalhaematoma. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1970 May;10(2):101-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1970.tb00410.x.

-

Maruki C, Nakajima M, Tsunoda A, Ebato M, Ikeya F. A case of giant expanding cephalhematoma: does the administration of blood coagulation factor XIII reverse symptoms? Surg Neurol. 2003 Aug;60(2):138-41; discussion 141. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00191-5.

-

Osaghae DO, Sule G, Benka-Coker J. Cephalhematoma causing severe anemia in the newborn: report of 2 cases. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2011 Jul;1(2):223-6.

-

LeBlanc CM, Allen UD, Ventureyra E. Cephalhematomas revisited. When should a diagnostic tap be performed? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1995 Feb;34(2):86-9. doi: 10.1177/00099228950340020.

-

Zimmermann P, Duppenthaler A. Infected cephalhaematoma in a five-week-old infant – case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Nov 4;16(1):636. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1982-4.

-

Yoon SD, Cho BM, Oh SM, Park SH. Spontaneous resorption of calcified cephalhematoma in a 9-month-old child: case report. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013 Mar;29(3):517-9. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-2008-1.

-

Daglioglu E, Okay O, Hatipoglu HG, Dalgic A, Ergungor F. Spontaneous resolution of calcified cephalhematomas of infancy: report of two cases. Turk Neurosurg. 2010 Jan;20(1):96-9.

-

Yoon SD, Cho BM, Oh SM, Park SH. Spontaneous resorption of calcified cephalhematoma in a 9-month-old child: case report. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013 Mar;29(3):517-9. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-2008-1.

-

Chida K, Kubo N, Suzuki T, Kidoguchi J, Komoribayashi N, Ogawa A. [Surgical treatment of ossified cephalhematoma: a case report]. No Shinkei Geka. 2008 Jun;36(6):529-33. Japanese. PMID: 18548894.

-

Singh I, Rohilla S, Siddiqui SA, Kumar P. Growing skull fractures: guidelines for early diagnosis and surgical management. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016 Jun;32(6):1117-22. doi: 10.1007/s00381-016-3061-y.

-

Tandon V, Garg K, Mahapatra AK. ‘Double skull’ appearance due to calcifications of chronic subdural hematoma and cephalhematoma: a report of two cases. Turk Neurosurg. 2013;23(6):815-7. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.6189-12.1.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Myasthenia gravis şi sarcina

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder affecting nearly 1 million individuals worldwide, being diagnosed typically in the second and thir...

Accidentul vascular cerebral perinatal – coşmarul neurodezvoltării fetale

Accidentul vascular cerebral perinatal este un sindrom polimorf cauzat de o leziune vasculară cerebrală. Apare între 20 de săptămâni de gestaţie şi...

Sarcina şi naşterea în timpul pandemiei de COVID-19. Implicaţii pentru gravidă şi naştere

In late December 2019, a series of pneumonia cases of unknown cause appeared in Wuhan City, Central China, which were reported to the World Health ...

Tipuri actuale de naştere şi impactul lor asupra mamei şi fătului

În urma evoluţiei modalităţii de naştere, am constatat, potrivit unui studiu observaţional efectuat în clinica noastră în perioada 2017-2021, o ten...