Uterine myomas affect 2-10% of pregnant women. They are hormone-dependent tumors, and 30% of them will increase in response to hormonal changes during pregnancy. Therefore, significant growth is expected in pregnancy, but, actually, most of them do not change in size. They are usually asymptomatic, but they may be associated with severe abdominal pain and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Conservative management is the first option. If the conservative treatment fails and the symptoms are severe, a myomectomy can be performed, with serious risks of severe hemorrhage, uterine rupture, miscarriage and preterm labor. We present the case of a 31-year-old primigravida presenting in our service for severe abdominal pain, pollakiuria and constipation. The ultrasound examination revealed a 13-week pregnancy, with no ultrasound signs of fetal structural abnormalities, and several fibroids, in contact with each other, developed as one fibroid mass, intramural and subserous, in the lower uterine segment and into both parametria, with a diameter of 100/95/87 mm. During the following weeks, the symptoms progressed, and the fibroid volume almost doubled. At 17 weeks of pregnancy, due to the severity of the symptoms, rapidly growing myomas and suggestive ultrasound aspect of degeneration, we performed a myomectomy. The surgery was uneventful. The patient was monitored weekly. Detailed second-trimester and third-trimester scans confirmed the normal pregnancy evolution. Doppler evaluation of both uterine arteries showed a normal spectrum. The fetal growth was favorable, at a percentile of 50 at 32 weeks of pregnancy. No short-term or long-term complications of the surgery have been noted so far. Myomectomy during pregnancy should be considered in cases of symptomatic uterine fibroids not responding to conservative management or in large or rapidly growing myomas, large or medium myomas located in the lower uterine segment, or deforming the placental site, following appropriate counseling of the patient regarding the associated risks.

Fibroamele uterine asociate sarcinii – este fezabilă miomectomia în sarcină? Review şi prezentare de caz

Uterine fibroids associated with pregnancy – is myomectomy during pregnancy feasible? Review and case presentation

First published: 29 octombrie 2023

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/ObsGin.71.3.2023.8944

Abstract

Rezumat

Mioamele uterine afectează 2-10% dintre femeile însărcinate. Sunt tumori dependente hormonal şi, în consecinţă, 30% dintre ele vor creşte ca răspuns la modificările hormonale ale sarcinii, însă, de fapt, majoritatea nu cresc semnificativ. De obicei sunt asimptomatice, dar pot fi asociate cu dureri abdominale severe şi complicaţii ale sarcinii. Managementul conservator este prima opţiune. Dacă tratamentul conservator eşuează şi simptomele sunt severe, poate fi efectuată miomectomia, cu riscuri importante, precum hemoragie severă, ruptură uterină, avort spontan sau travaliu prematur. Prezentăm cazul unei primigravide în vârstă de 31 de ani, care s-a prezentat în serviciul nostru pentru dureri abdominale severe, polachiurie şi constipaţie. Examenul ecografic a evidenţiat o sarcină de 13 săptămâni, fără semne ecografice de anomalii structurale fetale, dar mai multe fibroame, situate în contact, dezvoltate ca o singură masă fibromatoasă, intramural şi subseros, în segmentul uterin inferior şi în ambele parametre, cu diametrul de 100/95/87 mm. În următoarele săptămâni, simptomele au progresat, iar volumul masei fibromului aproape s-a dublat. La 17 săptămâni de sarcină, din cauza severităţii simptomelor, a creşterii rapide a masei tumorale şi a aspectului sugestiv ecografic al degenerării, s-a efectuat miomectomie. Operaţia a decurs fără complicaţii. Pacienta a fost monitorizată săptămânal în perioada următoare. Scanările detaliate din al doilea şi al treilea trimestru au confirmat evoluţia normală a sarcinii. Evaluarea Doppler a ambelor artere uterine şi a arterei ombilicale a arătat spectre normale. Creşterea fetală s-a menţinut normală, la percentila 50 la 32 de săptămâni de sarcină. Nu au fost observate complicaţii pe termen scurt sau lung ale intervenţiei chirurgicale. Miomectomia în timpul sarcinii trebuie luată în considerare în cazurile de fibrom uterin simptomatic care nu răspund la managementul conservator sau în mioame mari ori cu creştere rapidă, mioame mari sau medii localizate în segmentul inferior uterin ori care deformează locul placentar, în urma consilierii adecvate a pacientului cu privire la riscurile asociate.

Introduction

Uterine myomas are smooth muscle benign tumors, with a prevalence of 2-10% during pregnancy(1-3). The development of uterine fibroids is influenced by genetic factors and the hormonal levels of estrogen and progesterone(4-7). Therefore, their growth is expected during pregnancy, but most of them do not change significantly in size during pregnancy(6,8,9). It is a common belief that uterine myomas increase in size during pregnancy, but this happens in rare cases(10). The growth of uterine myomas in pregnancy cannot be predicted(11). Still, some studies found that, during the first and the second trimesters of pregnancy, the fibroids may remain unchanged, increase or even decrease in volume, or remain at the same size in the third trimester(12).

The presence of fibroids in pregnancy is usually asymptomatic, but they can be associated with possible complications(6).

The most common symptoms of uterine myomas in pregnancy, according to Spyropoulou et al. (2020), are abdominal pain, fever, abdominal heaviness, vomiting, constipation and vaginal bleeding. Other symptoms related to the presence of uterine fibroids might be urine retention, respiratory discomfort, uterine contractions and hydronephrosis(2).

The most common symptom is pain(13,14), caused by pressure of the fibroid itself or by torsion of a pedunculated myoma(6). The pelvic pain has been described to be more severe in posterior-located fibroids, larger than 30 mm in diameter than anterior-located ones(14).

The syndrome of painful myoma describes the association of severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and fever(15,16), and it is considered the major complication of myomas in pregnancy(17). The common causes of painful myoma syndrome are red or carneous degeneration(11), torsion of the pedicle, and infection or necrosis(18).

Leiomyomas can suffer several degenerative changes, such as hyaline degeneration or red or carneous degeneration, which is considered specific but not exclusively pregnancy-related. Often, they are causing pain and fever(16,19).

The miscarriage rate in pregnancy associated with submucosa myomas is 14%, almost double compared to the pregnancies without fibroids(20-22). However, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Sundermann et al. (2017), including more than 20,000 women, did not find any association between spontaneous abortion and uterine myomas(23).

When the uterine myomas have an increased size, they may cause pollakiuria by irritating the urinary bladder, along with an increased blood flow in pregnancy, retention of urine by compressing the bladder neck, or even urinary tract infections due to intermittent urinary retention caused by partial obstruction(6). Also, compression of large posterior myomas on the rectum may cause chronic constipation(24). Another, yet very rare, complication of posterior uterine wall myomas associated with a retroverted uterus is the pelvic incarceration of the pregnant uterus(6,25).

Premature rupture of membranes was significantly increased in pregnancies associated with fibroids, in a small study(26). Still, other studies do not support this finding(27).

The presence of uterine myomas may increase the risk of premature uterine contractions and premature birth(2,28). A retrospective cohort study performed in France, including almost 20,000 pregnant women, from which 301 had uterine myomas, has reported a 2.5-fold increased rate of preterm birth in pregnancies associated with uterine myomas(29).

The risk of placental abruption has been reported in some studies, occurring most in submucous and retroplacental fibroids having a diameter above 7-8 cm(29-32). Other studies found no correlation between placental abruption and fibroid(8,12).

Post-partum hemorrhage is more common in pregnancies associated with uterine myomas than in uncomplicated pregnancies(27,29). It is assumed that overdistension of the uterus due to the presence of fibroid predisposes to uterine atony and bleeding(33,34).

A distorted uterine cavity, related to fibroids, can cause fetal malpresentation(29,34-36), especially in breech cases(37). In rare cases, the fetus may be affected by the presence of the fibroid, causing fetal deformation (abnormal position of limbs, congenital torticollis and head deformities)(6,33).

After delivery, the fibroids may regress spontaneously or may complicate with torsion in the case of pedunculated fibroids or ischemic degeneration in the case of submucosal fibroids, providing an excellent environment for anaerobic bacterial culture and, therefore, puerperal fever and tachycardia associated with intense pelvic pain(6).

The mode of delivery in cases associated with uterine myomas is influenced by the number, size and location of the myomas. In large myomas cases, there is a higher incidence of caesarean delivery(37); however, the presence of uterine myomas does not contraindicate the trial of labor unless the myomas obstruct the birth canal. Therefore, patients with fibroids larger than 5 cm and located in the inferior uterine segment have an increased rate of caesarian delivery(29,38-41).

The first-line treatment of uterine myomas in pregnancy is represented by conservative management of the symptoms, with symptomatic treatment and bed rest. When, despite maximal analgesics and prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, the abdominal pain persists, it becomes more severe in large or rapidly growing myomas, large or medium myomas located in the lower uterine segment, or deforming the placental site, the conservative treatment fails and the surgical treatment is recommended(16).

A systematic review of myomectomy in pregnancy reports a small number of complications. In this review, most fibroids were subserous and subserous pedunculated, located at the uterine fundus, with no contact with the placenta. In cases of single and multiple myomectomies, fibroids removed were intramural and subserous located at the uterine fundus. This review includes 76 myomectomies by laparotomy, 15 by laparoscopy, four by vaginal approach, and one case of operative hysteroscopy(2).

Antibiotic prophylaxis and tocolysis before and during the surgery are recommended for preoperative care. Some authors consider medial laparotomy the best approach(15,16,18,24,42-73). Other authors advocate for a laparoscopic approach(1,74-83). Vaginal surgery is a valid option for submucosal pediculated myomas located in the cervical canal(49,84-86).

The main bias in myomectomy in pregnant women is the increased risk of massive bleeding. Outside of pregnancy, controlled hypotensive anesthesia, tourniquets and local injections of vasoconstrictive agents represent valid options to prevent intraoperative hemorrhage, but in pregnancy those are not allowed. To reduce the risk of massive bleeding, Suwandinata et al. (2008) described a technique of interrupted sutures placed around the myoma to secure the blood vessels encircling it before performing myomectomy(16).

Spyropoulou et al. (2020)(2), in a systematic review of 97 cases of myomectomy in pregnancy, reported surgery complications in less than 10% of the cases, as follows: moderate vaginal bleeding(24), cervical shortening with cervical positive culture(45), miscarriage(15,42,45,57,70,84), rupture of membrane shortly after the surgery(84), hematoma of the uterine scar(49), uterine rupture following myometrial necrosis and abscess(77), and a case with purulent chorioamnionitis(42).

Routine myomectomy during caesarean section is not recommended, due to an increased risk of massive bleeding, but it might be feasible and safe in tiny and pedunculated myomas(87).

Case report

We present the case of a 31-year-old primigravida presenting with severe abdominal pain, pollakiuria and constipation. The patient did not report a relevant medical personal or familial history.

The gynecological exam revealed an enlarged uterus for gestational age, with the uterine fundus elevated to the umbilical scar.

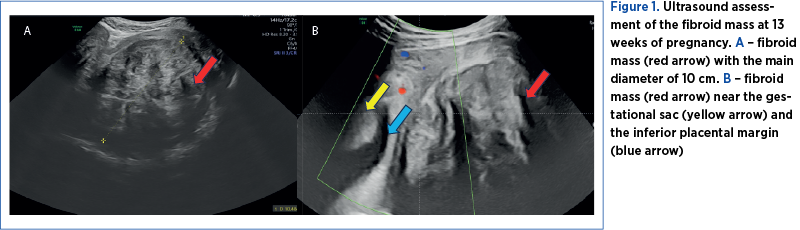

The ultrasound examination revealed a 13-week pregnancy, with no ultrasound signs of fetal structural abnormalities, and several fibroids, in contact with each other, developed as one fibroid mass, intramural and subserous, in the lower uterine segment and into both right and left parametria, with a diameter of 100/95/87 mm and a volume of 826 cm3 (Figure 1A). The placental attachment was on the anterior uterine wall, with no contact with the fibroid mass, but in close proximity – 3 mm (Figure 1B).

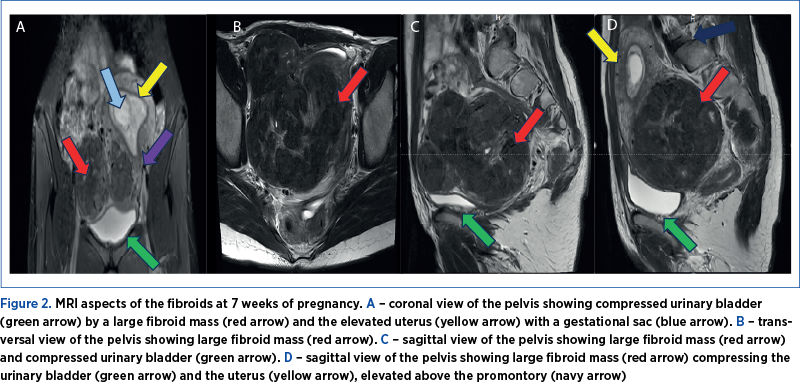

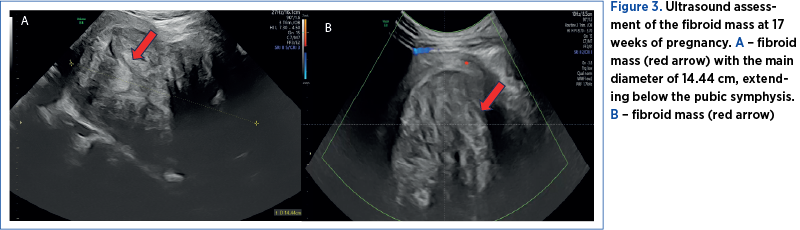

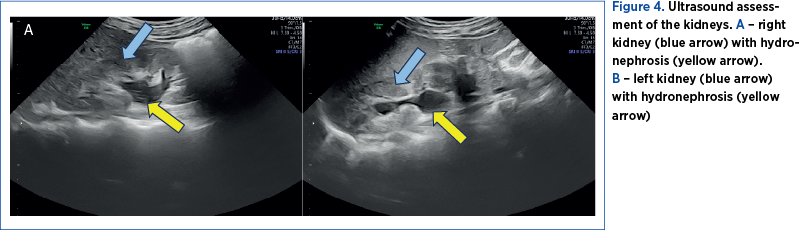

The first pregnancy ultrasound assessment, performed at 7 gestational weeks, described uterine fibroids, and a pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was recommended. The results of the pelvic MRI confirmed the ultrasound report. Moreover, the MRI report provided additional information about the development of the myomas, submucosal and sub-serosal, with more than 50% intramural development, and their mass effect on the uterine cavity, bladder and rectum (Figure 2 A-D).At first, we recommended a urinary test for infections, and analgetic and prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors treatment for the management of pelvic pain. During the following weeks, the symptoms progressed, restricting daily activities as the fibroid volume increased, reaching a diameter of 150/90/95 mm, with an almost double volume (1425 cm3). Also, their ultrasound aspect slightly changed to a lower echoic heterogenous aspect (Figure 3 A, B). The severe pelvic pain, along with the increased size of the fibroid and the suggestive ultrasound aspect raised the suspicion of fibroid degeneration. The increased size of the myomas caused yet another symptomatic complication – bilateral ureteral compression with hydronephrosis (Figure 4 A, B).

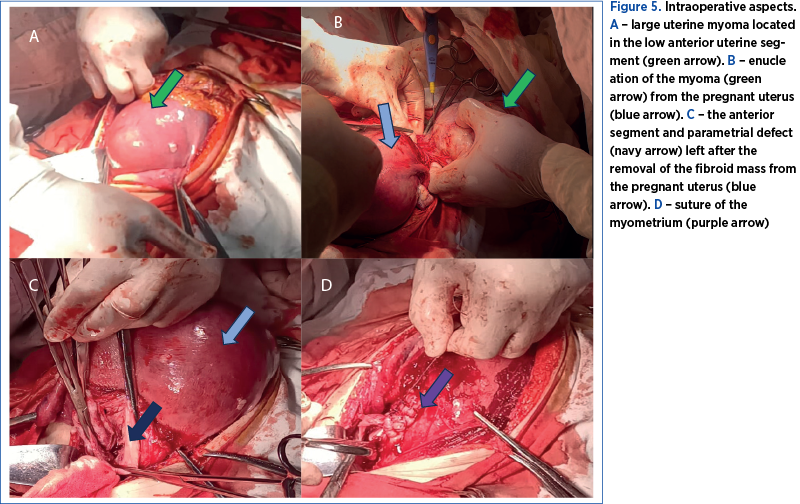

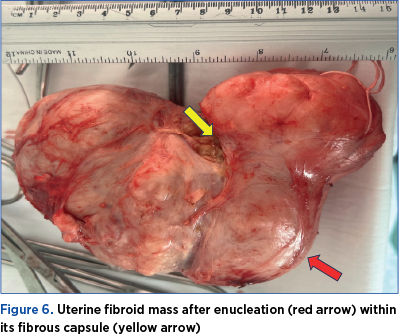

Therefore, at 17 weeks of pregnancy, due to severe abdominal pain, interfering with daily activities, not responding to analgesics, the rapidly growing myomas and the ultrasound aspect, we decided to perform a myomectomy by midline laparotomy approach. We found a 150/150/90 mm fibromatous mass developed in the inferior uterine segment, the left parametrium and the right parametrium near the right uterine artery, and we removed it by enucleation (Figure 5 A, B). The removal of the fibroid mass was uneventful, as we avoided injury to the right uterine artery by performing the mass dissection within its capsule (Figure 6). The myometrium was sutured in two layers using resorbable sutures (Figure 5 C, D). Overall, the surgery was uneventful. The postoperative recovery went well, with antibiotics prophylaxis, low-molecular-weight heparin, progesterone, tocolytic and antispastic treatment, and analgesics for managing postoperative pain.

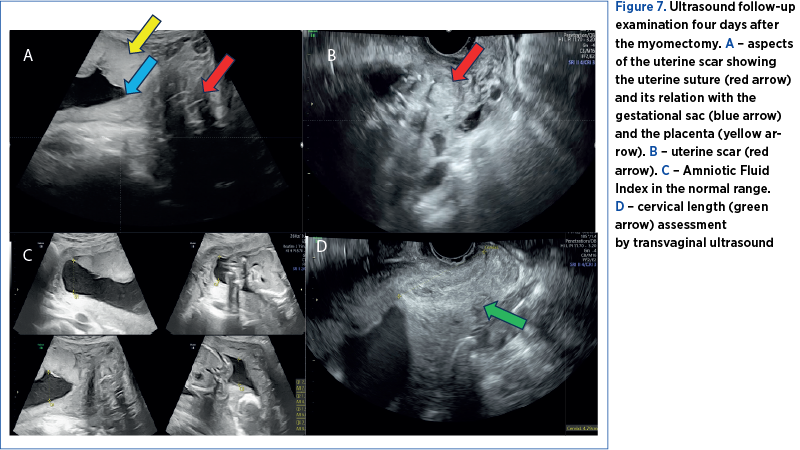

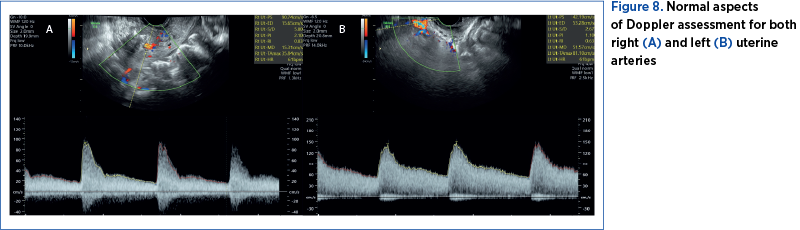

The patient was discharged after four days. At that time, the pregnancy evaluation revealed normal ultrasound relations. The uterine scar was visualized on ultrasound with a normal aspect and no signs of hematomas (Figure 7 A, B). The uterine artery Doppler interrogation showed indices within the normal range (Figure 8 A, B). We also calculated a normal amniotic fluid index (Figure 7C).

The cervical length was difficult to assess before the surgery due to the position of the fibroid mass, which distorted the uterine anatomy, pushing the cervix in a posterior-lateral position, difficult to assess by ultrasound or by clinical examination, since the myomatous mass extended till the vaginal introitus. Therefore, we only assessed the cervical length after the surgery in several examinations and maintained above the normal cutoff value (Figure 7D).

The patient was monitored weekly. A detailed second-trimester anomaly scan was performed at 22 weeks. It showed no signs of fetal structural abnormalities, an estimated fetal weight at percentile 30, and a pulsatility index within normal ranges for both uterine and umbilical arteries.

The histopathological exam revealed edematous degeneration of the myomas, as we suspected on ultrasound.

Overall, the mother and the fetus had a good follow-up assessment after myomectomy. The last follow-up exam performed at 32 weeks showed normal growth, with an estimated fetal weight at the 55th percentile.

Discussion

Uterine myomas have a relatively high incidence in pregnant women, at about 10%(1-3). It is well known that genetics and hormonal levels of estrogen and progesterone influence the development and growth of myomas(4-7). Our patient has no familial history of uterine myomas or other gynecological-related conditions. Regarding the hormonal influence on fibroid growth, studies show that the high levels of estrogens and progesterone in pregnancy do not usually determine a significant development of uterine myomas, most of them remaining at the same size during the pregnancy. However, in our case, some of them may have a rapid growth(12), where the fibroid mass almost doubled the volume in four weeks.

Fibroids in pregnancy are usually asymptomatic, but their presence may influence the pregnancy outcome, depending on the size, location and associated symptoms(6). The most common symptom is severe abdominal pain, accompanied, in large myomas, by compression symptoms(2). In our case, along with the severe abdominal pain, the fibroid mass compressed both the bladder and the rectum, producing urinary symptoms such as pollakiuria and digestive symptoms such as constipation. The first line of treatment is conservative, with analgesics and prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors(16). Despite maximal analgesic and prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors treatment, the symptoms of our patient progressed. Furthermore, the compression due to the increasing size of the myoma added new symptoms, such as hydronephrosis. Along with the rapid growth of the myomas, we also noticed a change in the ultrasound aspect, suggesting the degeneration of the fibroid mass.

Ultrasound examination is the first-line imaging method to diagnose uterine myomas, being relatively cheap and available in every clinic(88,89). Magnetic resonance imaging is the most accurate imaging technique for detecting, localizing and characterizing large myomas. This investigation is considered safe in pregnancy, offering advantages over ultrasound in assessing myoma burden(89,90). In our case, MRI brought essential information about the location of the myomas, from G2 to G5, according to FIGO staging of uterine myomas(91). Their position regarding the gestational sac, the cervix, and the compression on the uterine cavity, urinary bladder and rectum were also better exposed with MRI.

The myomectomy in pregnancy can be performed by laparotomy, laparoscopy, and even vaginal surgery in selected cases(2). Our approach by laparotomy was guided by the increased size of the myomas, estimated at almost 15 centimeters. When performing a surgical procedure on a pregnant uterus, the manipulation must be gentle, to reduce the risk of additional pressure on the pregnant uterus. Increased vascularization in pregnancy increases even more the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage. Due to the sensitivity of the fetus to hypoxia, hypotensive controlled anesthetic techniques, use of tourniquets and local injections of vasoconstrictive agents are contraindicated(16). In the attempt to prevent massive intraoperative hemorrhage, a technique of interrupted sutures placed around the myoma to secure the blood vessels encircling was described(16). In our experience, a carefully performed myomectomy within the fibrous capsule of the myoma is considered safe, with minimal blood loss. The site and the size of the myoma may also represent a technique challenge. The fibroid mass of our patient was estimated to be around 15 cm, developed on the anterior uterine segment and the right parametrium, in close rapport with the right uterine artery. After the urinary bladder dissection and myomectomy, we chose to perform a double-layer suture of the myometrium. By keeping the dissection inside the capsule, along with a careful myometrial suture, we managed to avoid the uterine artery injury confirmed by normal Doppler spectrum on further examinations.

As recommended, antibiotic prophylaxis and tocolysis were administrated before surgery(16). Afterward, we continued the tocolytic treatment along with progesterone, antispastic treatment, low-molecular-weight heparin, and analgesics for the management of pain.

After avoiding intraoperative massive hemorrhage and pregnancy loss, we carefully monitored the uterine scar for hematoma. The scar had an uneventful evolution, with a normal aspect on ultrasound.

Further follow-ups of the pregnancy were made, with a favorable growth of the fetus.

The increased size of the myomas, blocking the birth canal, would have represented an absolute indication of caesarean delivery(37). Even after the myoma removal, vaginal delivery is not recommended, due to the risk of uterine rupture(92).

Conclusions

Myomectomy should be considered in pregnant women with symptomatic uterine fibroids, not responding to conservative management, large or rapidly growing, located in the lower uterine segment, or deforming the placental site.

The procedure may associate an increased rate of complications during pregnancy, but with the right preparation and experience, it is considered a safe procedure.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

- Saccardi C, Visentin S, Noventa M, Cosmi E, Litta P, Gizzo S. Uncertainties about laparoscopic myomectomy during pregnancy: A lack of evidence or an inherited misconception? A critical literature review starting from a peculiar case. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2015;24(4):189–94.

- Spyropoulou K, Kosmas I, Tsakiridis I, Mamopoulos A, Kalogiannidis I, Athanasiadis A, et al. Myomectomy during pregnancy: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;254:15–24.

- Laughlin SK, Baird DD, Savitz DA, Herring AH, Hartmann KE. Prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in the first trimester of pregnancy: an ultrasound-screening study. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):630–5.

- Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, Bull D, Yeates D, Casagrande JT. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6543):359–62.

- Cramer SF, Patel A. The frequency of uterine leiomyomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;94(4):435–8.

- Zaima A, Ash A. Fibroid in pregnancy: characteristics, complications, and management. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1034):819–28.

- Reis FM, Bloise E, Ortiga-Carvalho TM. Hormones and pathogenesis of uterine fibroids. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2016;34:13–24.

- Muram D, Gillieson M, Walters JH. Myomas of the uterus in pregnancy: ultrasonographic follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138(1):16–9.

- Strobelt N, Ghidini A, Cavallone M, Pensabene I, Ceruti P, Vergani P. Natural history of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 1994;13(5):399–401.

- Neiger R, Sonek JD, Croom CS, Ventolini G. Pregnancy-related changes in the size of uterine leiomyomas. J Reprod Med. 2006;51(9):671–4.

- Phelan JP. Myomas and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1995;22(4):801–5.

- Lev-Toaff AS, Coleman BG, Arger PH, Mintz MC, Arenson RL, Toaff ME. Leiomyomas in pregnancy: sonographic study. Radiology. 1987;164(2):375–80.

- Ouyang DW, Economy KE, Norwitz ER. Obstetric complications of fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006 Mar;33(1):153–69.

- Deveer M, Deveer R, Engin-Ustun Y, Sarikaya E, Akbaba E, Senturk B, et al. Comparison of pregnancy outcomes in different localizations of uterine fibroids. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39(4):516–8.

- Lolis DE, Kalantaridou SN, Makrydimas G, Sotiriadis A, Navrozoglou I, Zikopoulos K, et al. Successful myomectomy during pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(8):1699–702.

- Suwandinata FS, Gruessner SEM, Omwandho COA, Tinneberg HR. Pregnancy-preserving myomectomy: Preliminary report on a new surgical technique. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2008;13(3):323–6.

- Katz VL, Dotters DJ, Droegemeuller W. Complications of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Apr;73(4):593–6.

- Celik C, Acar A, Ciçek N, Gezginc K, Akyürek C. Can myomectomy be performed during pregnancy? Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2002;53(2):79–83.

- Robboy SJ, Bentley RC, Butnor K, Anderson MC. Pathology and pathophysiology of uterine smooth-muscle tumors [cited 2023 Oct 29]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11035982/

- Valli E, Zupi E, Marconi D, Vaquero E, Giovannini P, Lazzarin N, et al. Hysteroscopic findings in 344 women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(3):398–401.

- Benson CB, Chow JS, Chang-Lee W, Hill JA, Doubilet PM. Outcome of pregnancies in women with uterine leiomyomas identified by sonography in the first trimester. J Clin Ultrasound. 2001;29(5):261–4.

- Eldar-Geva T, Meagher S, Healy DL, MacLachlan V, Breheny S, Wood C. Effect of intramural, subserosal, and submucosal uterine fibroids on the outcome of assisted reproductive technology treatment. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(4):687–91.

- Sundermann AC, Velez Edwards DR, Bray MJ, Jones SH, Latham SM, Hartmann KE. Leiomyomas in Pregnancy and Spontaneous Abortion: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(5):1065–72.

- Leach K, Khatain L, Tocce K. First trimester myomectomy as an alternative to termination of pregnancy in a woman with a symptomatic uterine leiomyoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;10;5:571.

- Kim HS, Park JE, Kim SY, et al. Incarceration of early gravid uterus with adenomyosis and myoma: report of two patients managed with uterine reduction. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61(5):621–5.

- Pandit U, Singh M, Ranjan R. Assessment of Maternal and Fetal Outcomes in Pregnancy Complicated by Fibroid Uterus. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22052.

- Klatsky PC, Tran ND, Caughey AB, Fujimoto VY. Fibroids and reproductive outcomes: a systematic literature review from conception to delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):357–66.

- Girault A, Le Ray C, Chapron C, Goffinet F, Marcellin L. Leiomyomatous uterus and preterm birth: an exposed/unexposed monocentric cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(4):410.e1-410.e7.

- Jenabi E, Ebrahimzadeh Zagami S. The association between uterine leiomyoma and placenta abruption: A meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(22):2742–6.

- Rice JP, Kay HH, Mahony BS. The clinical significance of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 Pt 1):1212–6.

- Exacoustos C, Malzoni M, Di Giovanni A, et al. Ultrasound mapping system for the surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(1):143-150.e2.

- Coronado GD, Marshall LM, Schwartz SM. Complications in pregnancy, labor, and delivery with uterine leiomyomas: a population-based study. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;95(5):764–9.

- Coutinho LM, Assis WA, Spagnuolo-Souza A, Reis FM. Uterine Fibroids and Pregnancy: How Do They Affect Each Other? Reprod Sci. 2022;29(8):2145–51.

- Exacoustòs C, Rosati P. Ultrasound diagnosis of uterine myomas and complications in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(1):97–101.

- Qidwai GI, Caughey AB, Jacoby AF. Obstetric outcomes in women with sonographically identified uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):376–82.

- Ciavattini A, Clemente N, Delli Carpini G, Di Giuseppe J, Giannubilo SR, Tranquilli AL. Number and size of uterine fibroids and obstetric outcomes. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2015;28(4):484–8.

- Zhao R, Wang X, Zou L, et al. Adverse obstetric outcomes in pregnant women with uterine fibroids in China: A multicenter survey involving 112,403 deliveries. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187821.

- Karlsen K, Schiøler Kesmodel U, Mogensen O, Humaidan P, Ravn P. Relationship between a uterine fibroid diagnosis and the risk of adverse obstetrical outcomes: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e032104.

- Lam SJ, Best S, Kumar S. The impact of fibroid characteristics on pregnancy outcome. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014;211(4):395.e1-395.e5.

- Michels KA, Edwards DRV, Baird DD, Savitz DA, Hartmann KE. Uterine Leiomyomata and Cesarean Birth Risk: A Prospective Cohort with Standardized Imaging. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(2):122–6.

- Vergani P, Locatelli A, Ghidini A, Andreani M, Sala F, Pezzullo JC. Large uterine leiomyomata and risk of cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):410–4.

- De Carolis S, Fatigante G, Ferrazzani S, et al. Uterine myomectomy in pregnant women. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2001;16(2):116–9.

- Wittich AC, Salminen ER, Yancey MK, Markenson GR. Myomectomy during early pregnancy. Mil Med. 2000;165(2):162–4.

- Bhatla N, Dash BB, Kriplani A, Agarwal N. Myomectomy during pregnancy: A feasible option. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2009;35(1):173–5.

- Basso A, Catalano MR, Loverro G, Nocera S, Di Naro E, Loverro M, et al. Uterine Fibroid Torsion during Pregnancy: A Case of Laparotomic Myomectomy at 18 Weeks’ Gestation with Systematic Review of the Literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;2017:4970802.

- Kim TH, Lee HH. How should painful cystic degeneration of myomas be managed during pregnancy? A case report and review of the literature. Iran J Reprod Med. 2011;9(3):243–6.

- Hasbargen U, Strauss A, Summerer-Moustaki M, et al. Myomectomy as a Pregnancy-Preserving Option in the Carefully Selected Patient. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 2002;17(2):101–3.

- Kobayashi F, Kondoh E, Hamanishi J, Kawamura Y, Tatsumi K, Konishi I. Pyomayoma during pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39(1):383–9.

- Fuchs A, Dulska A, Sikora J, Czech I, Skrzypulec-Plinta V, Drosdzol-Cop A. Symptomatic uterine fibroids in pregnancy - wait or operate? Own experience. Ginekol Pol. 2019;90(6):320–4.

- Tong C, Wang Y, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Xu Y, Wang W. Spontaneous reduction of an incarcerated gravid uterus after myomectomy in the second trimester. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(9):e14731.

- Okonkwo JEN, Udigwe GO. Myomectomy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27(6):628–30.

- Usifo F, Macrae R, Sharma R, Opemuyi IO, Onwuzurike B. Successful myomectomy in early second trimester of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27(2):196–7.

- Allameh Z, Allameh T. Successful Myomectomy in the Second Trimester of Pregnancy. Adv Biomed Res. 2019;8:60.

- Umezurike C, Feyi-Waboso P. Successful myomectomy during pregnancy: a case report. Reprod Health. 2005;2:6.

- Kasum M. Hemoperitoneum caused by a bleeding myoma in pregnancy. Acta Clin Croat. 2010;49(2):197–200.

- Lozza V, Pieralli A, Corioni S, Longinotti M, Penna C. Multiple laparotomic myomectomy during pregnancy: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(3):613–6.

- Majid M, Khan GQ, Wei LM. Inevitable myomectomy in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17(4):377–8.

- Michalas SP, Oreopoulou FV, Papageorgiou JS. Myomectomy during pregnancy and Caesarean section. Human Reproduction. 1995;10(7):1869–70.

- Doerga-Bachasingh S, Karsdorp V, Yo G, van der Weiden R, van Hooff M. Successful myomectomy of a bleeding myoma in a twin pregnancy. JRSM Short Rep. 2012;3(2):13.

- Moruzzi MC, Moro F, Bolomini G, et al. Intraoperative ultrasound assistance during myomectomy in pregnant woman. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55(6):840–1.

- Leite GK, Korkes HA, Viana Ade T, Pitorri A, Kenj G, Sass N. Miomectomia em gestação de segundo trimestre: relato de caso [Myomectomy in the second trimester of pregnancy: case report]. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2010;32(4):198-201.

- Alanis MC, Mitra A, Koklanaris N. Preoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Antepartum Myomectomy of a Giant Pedunculated Leiomyoma. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;111(2 Part 2):577.

- Donnez J, Pirard C, Smets M, Polet R, Feger C, Squifflet J. Unusual growth of a myoma during pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(3):632–3.

- Valenti G, Milone P, D’Amico S, et al. Use of pre-operative imaging for symptomatic uterine myomas during pregnancy: a case report and a systematic literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299(1):13–33.

- Pelissier-Komorek A, Hamm J, Bonneau S, Derniaux E, Hoeffel-Fornes C, Graesslin O. Fibrome et grossesse: quand le traitement médical ne suffit pas. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 2012;41(3):307–10.

- Shafiee M, Nor Azlin M, Arifuddin D. A Successful Antenatal Myomectomy. Malays Fam Physician. 2012;7(2–3):42–5.

- Dracea L, Codreanu D. Vaginal birth after extensive myomectomy during pregnancy in a 39-year-old nulliparous woman. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;26(4):374–5.

- Tabandeh A, Besharat M. Successful myomectomy during pregnancy. Tabandeh. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences Old Website. [cited 2023 Oct 29]. https://www.pjms.com.pk/index.php/pjms/article/view/2079/600

- Salih H, Sarsam R, Abed N, Yassin W, Haque M. Successful Myomectomy during Pregnancy for a Large Uterine Fibroid Causing Intestinal Obstruction: Report of a Case Case Report. Journal of Young Pharmacists. 2015;7(4):399-402.

- Burton CA, Grimes DA, March CM. Surgical management of leiomyomata during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74(5):707–9.

- Vázquez Camacho EE, Cabrera Carranco E, Sánchez Herrera RG. Mioma pediculado torcido en una mujer embarazada. Reporte de caso [Pedunculated twisted myoma and pregnancy. Case report]. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2009;77(9):441-444.

- Domenici L, Di Donato V, Gasparri ML, Lecce F, Caccetta J, Panici PB. Laparotomic Myomectomy in the 16th Week of Pregnancy: A Case Report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:154347.

- Jhalta P, Negi SG, Sharma V. Successful myomectomy in early pregnancy for a large asymptomatic uterine myoma: case report. Pan Afr Med J. 201613;24:228.

- Macciò A, Madeddu C, Kotsonis P, Caffiero A, Desogus A, Pietrangeli M, et al. Three cases of laparoscopic myomectomy performed during pregnancy for pedunculated uterine myomas. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286(5):1209–14.

- Currie A, Bradley E, McEwen M, Al-Shabibi N, Willson PD. Laparoscopic Approach to Fibroid Torsion Presenting as an Acute Abdomen in Pregnancy. JSLS. 2013;17(4):665–7.

- Melgrati L, Damiani A, Franzoni G, Marziali M, Sesti F. Isobaric (gasless) laparoscopic myomectomy during pregnancy. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2005;12(4):379–81.

- Sentilhes L, Sergent F, Verspyck E, Gravier A, Roman H, Marpeau L. Laparoscopic myomectomy during pregnancy resulting in septic necrosis of the myometrium. BJOG. 2003;110(9):876–8.

- Kosmidis C, Pantos G, Efthimiadis C, Gkoutziomitrou I, Georgakoudi E, Anthimidis G. Laparoscopic Excision of a Pedunculated Uterine Leiomyoma in Torsion as a Cause of Acute Abdomen at 10 Weeks of Pregnancy. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:505–8.

- Pelosi MA, Pelosi MA, Giblin S. Laparoscopic removal of a 1500-g symptomatic myoma during the second trimester of pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2(4):457–62.

- Fanfani F, Rossitto C, Fagotti A, Rosati P, Gallotta V, Scambia G. Laparoscopic Myomectomy at 25 Weeks of Pregnancy: Case Report. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2010;17(1):91–3.

- Zhao X, Chen L, Zeng W, Jin B, Du W. Laparoscopic tumorectomy for a primary ovarian leiomyoma during pregnancy: A case report. Oncology Letters. 2014;8(6):2523.

- Ardovino M, Ardovino I, Castaldi MA, Monteverde A, Colacurci N, Cobellis L. Laparoscopic myomectomy of a subserous pedunculated fibroid at 14 weeks of pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:545.

- Son CE, Choi JS, Lee JH, Jeon SW, Bae JW, S. Seo S. A case of laparoscopic myomectomy performed during pregnancy for subserosal uterine myoma. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2011;31(2):180–1.

- Kilpatrick CC, Adler MT, Chohan L. Vaginal myomectomy in pregnancy: a report of two cases. South Med J. 2010;103(10):1058–60.

- Obara M, Hatakeyama Y, Shimizu Y. Vaginal Myomectomy for Semipedunculated Cervical Myoma during Pregnancy. AJP Rep. 2014;4(1):37–40.

- Demirci F, Somunkiran A, Safak AA, Ozdemir I, Demirci E. Vaginal removal of prolapsed pedunculated submucosal myoma during pregnancy. Adv Therapy. 2007;24(4):903–6.

- Tîrnovanu MC, Lozneanu L, Tîrnovanu ŞD, et al. Uterine Fibroids and Pregnancy: A Review of the Challenges from a Romanian Tertiary Level Institution. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(5):855.

- De La Cruz MSD, Buchanan EM. Uterine Fibroids: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(2):100–7.

- Shwayder J, Sakhel K. Imaging for uterine myomas and adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(3):362–76.

- Lum M, Tsiouris AJ. MRI safety considerations during pregnancy. Clin Imaging. 2020;62:69–75.

- Knipe H, El-Feky M, Rasuli B. FIGO classification system for uterine leiomyoma. [cited 2023 Oct 29]. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/figo-classification-system-foruterine-leiomyoma?lang=us

- Romanian Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Caesarean Section Clinical Guide. https://sogr.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/24-Operatia-cezariana.pdf

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Prognosticul în cazul pentalogiei lui Cantrell

Pentalogia lui Cantrell este un sindrom congenital rar, considerat letal, care asociază în forma sa completă următoarele cinci defecte: defect la n...

Consilierea în agenezia ductului venos secundară venei cave inferioare întrerupte

The ultrasound (US) examination of the fetal venous system has exposed a wide spectrum of malformations.

Impactul fibroamelor asupra ratei fertilităţii. Management chirurgical şi rezultate obstetricale

Fibroamele uterine sunt cea mai frecventă tumoră benignă la femeile de vârstă reproductivă. Atunci când sunt simptomatice, se manifestă cu durere s...

Provocări în evaluarea feţei fetale – diagnostic şi management

The ultrasound assessment of the fetal face is the first way of interaction of the parents with their unborn baby, therefore recent achievements in...