Omfalocel, scrot bifid, hipospadias şi micropenis: rezultate clinice în cazuri cu cariotip normal

Omphalocele, bifid scrotum, hypospadias and micropenis: clinical outcome in cases with normal karyotype

Abstract

Background. This study aims to describe the omphalocele, hypospadias, bifid scrotum and micropenis association characteristics, along with the care, prenatal diagnosis strategies and postnatal outcomes. We also present a case with this unusual association of malformations in a fetus with a normal male karyotype. Methodology. For this study, we present a case with detailed imaging and follow-up investigations before and after birth. Also, we searched the literature regarding the management of this complex malformation, and we present the review results. Results. According to literature, the following syndromes were linked to the spectrum of omphalocele-hypospadias: trisomy 13, trisomy 18, trisomy 21, 45X, 47XXY and 47XXX, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and 2q22.1q22.3 deletion. According to our complex investigations, the omphalocele, bifid scrotum, hypospadias and micropenis, in the case of our patient, were isolated, despite literature findings. In the absence of associated major structural or genetic abnormalities, the management was conservative, with a good outcome. Conclusions. Structural anomalies can often appear alone, spontaneously or in association with other structural anomalies as part of syndromes. According to the detailed prenatal and postnatal evaluation, micropenis-hypospadias and omphalocele associations were isolated in our case, despite the literature findings. Fetal growth and well-being should be monitored, as intrauterine fetal growth restriction may occur.Keywords

prenatal diagnosisomphalocelemicropenisbifid scrotumabdominal wall defectgrowth restrictionultrasoundanomaly scanRezumat

Context. Acest studiu îşi propune să descrie caracteristicile, monitorizarea şi managementul unei malformaţii complexe: omfalocel, hipospadias, scrot bifid şi micropenis, alături de strategiile de diagnostic prenatal şi rezultatele postnatale. Prezentăm şi un caz cu această asociere neobişnuită de malformaţii, la un făt cu cariotip masculin normal. Metodologie. Pentru acest studiu, prezentăm un caz cu imagini detaliate şi investigaţii de urmărire înainte şi după naştere. De asemenea, am căutat în literatura de specialitate date cu privire la gestionarea acestei malformaţii complexe şi prezentăm rezultatele revizuirii. Rezultate. Conform literaturii de specialitate, următoarele sindroame au fost legate de spectrul omfalocel-hipospadias: trisomia 13, trisomia 18, trisomia 21, 45X, 47XXY şi 47XXX, sindromul Beckwith-Wiedemann şi deleţia 2q22.1q22.3. Conform investigaţiilor noastre detaliate, această anomalie complexă a fost izolată în cazul pacientului nostru, în ciuda constatărilor din literatură. În absenţa unor anomalii structurale sau genetice majore asociate, managementul a fost conservator, cu un rezultat postnatal favorabil. Concluzii. Anomaliile structurale pot apărea izolate sau în asociere cu alte anomalii structurale ca parte a sindroamelor. În cazul nostru, asocierile micropenis-hipospadias şi omfalocel au fost izolate, conform evaluării detaliate prenatale şi postnatale, deşi datele din literatură au confirmat alte asocieri genetice sau malformative în toate cazurile. Dezvoltarea şi starea de sănătate a fătului trebuie monitorizate, deoarece poate apărea o restricţie a creşterii fetale intrauterine.Cuvinte Cheie

diagnostic prenatalomfalocelmicropenisscrot bifiddefecte de perete abdominalrestricţie de creştereecografiemorfologie fetalăIntroduction

One of the most prevalent congenital abnormalities of the anterior abdominal wall is the omphalocele (exomphalos). The midgut and other abdominal organs, including the liver, spleen and gonads, are frequently located within this midline defect, which develops near the umbilical ring(1). The extern amniotic layer, the middle Wharton’s jelly layer, and the intern peritoneal layer form a three-layer covering for the herniated abdominal contents(2). The accepted standard of care states routine prenatal screening that should include highlighting the integrity of the anterior abdominal wall and the insertion of the umbilical cord (ISUOG Practice Guidelines updated: performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan) and the diagnosis of the abdominal wall defect and related anomalies. An early diagnosis enables prenatal counseling and safe delivery at a tertiary care facility with a multidisciplinary team that includes neonatologists, obstetricians and pediatric surgeons(3). Over 70% of cases of omphalocele have additional chromosomal abnormality(4,5). On the long-term survival, related or supplementary anomalies make a significant difference(6).

Micropenis is a condition that is part of a larger group of issues that are collectively referred to as inconspicuous penis. Still, it differs fundamentally from the other diagnostics in this category, such as webbed penis and buried penis, the main issue being the size of the penis itself rather than the skin that covers it. Although iatrogenic causes are rarely found, the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is typically the etiology of this illness(7). The range of prenatal anomalies that can be found before birth includes atypical genitalia development (AGD). These include complex abnormalities for which it is still difficult to determine the sex, such as clitoromegaly, hypospadias and epispadias(8). There is still no link between prenatal and postnatal observations, and many prenatal diagnoses are incorrect. For example, the lack of distinct boundaries between clitoromegaly and micropenis before birth is a sign of potential confusion(9).

One of the most prevalent congenital abnormalities in men is hypospadias. Penile curvature, a ventrally lacking hooded foreskin, and proximal displacement of the urethral opening are the usual characteristics of the syndrome. The urethral meatus is situated distally on the penile shaft in roughly 70% of cases; this is regarded as a moderate variant unrelated to other urogenital abnormalities. The other thirty percent are proximal and frequently more complex(10).

In its extreme form of the bifid scrotum, the two scrotal sacs are widely separated, with a fully opened urethra in the form of proximal hypospadias, and the scrotal raphe is not visible. Bifid scrotum is an uncommon congenital defect that affects the midline of the scrotum. Although bifid scrota are typically linked to androgen insensitivity syndrome, hypogonadism and penoscrotal hypospadias, they can also be an isolated genital abnormality linked to maldevelopment and uncommon somatic syndromes(11).

For the prenatal and newborn population, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a significant and sometimes silent cause of severe illness and mortality. It is described as a fetal growth rate that is below average for the particular infant’s growth potential(12). Obstetricians frequently diagnose intrauterine growth restriction, which entails a higher risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity. The identification of IUGR is essential, because careful assessment and management can lead to a successful outcome(13).

This article’s goal is to describe omphalocele and micropenis care, along with prenatal diagnosis strategies and postnatal outcomes.

Case presentation

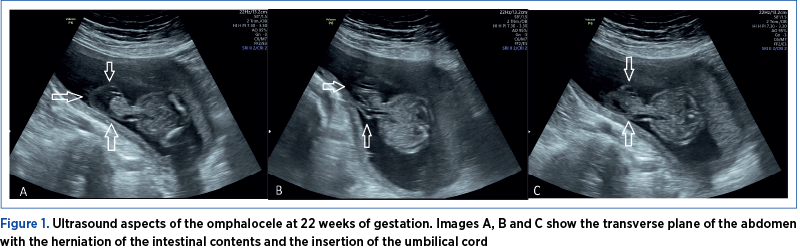

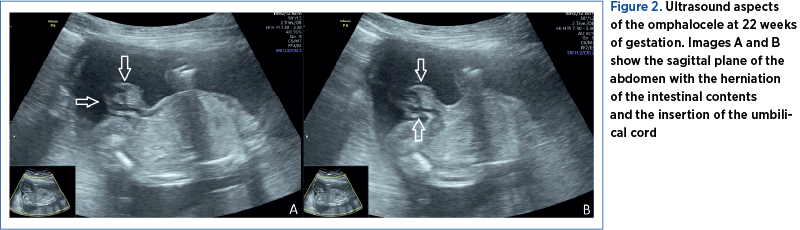

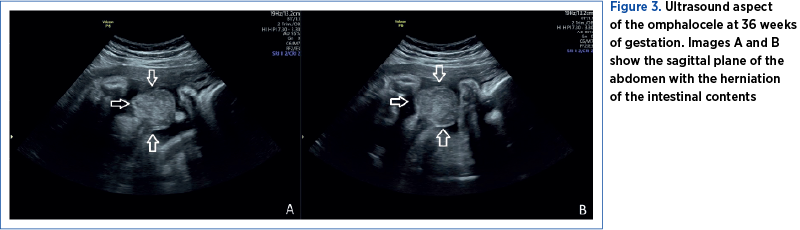

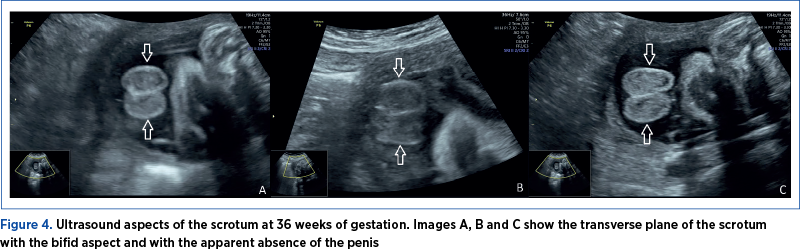

The investigations were conducted in the County Emergency Clinical Hospital of Craiova, a tertiary center. The examination was performed using a Voluson P8 GE HealthCare medical system. A 24-year-old pregnant patient addressed the Prenatal Diagnosis Unit of the Emergency County Hospital of Craiova for second-trimester invasive genetic testing (amniocentesis – screening of chromosomes 13, 18, 21 aneuploidy, X and Y and fetal karyotype by quantitative fluorescent-polymerase chain reaction [QF-PCR]). At 21 weeks of gestation, the fetus was presumed to have an abdominal wall defect (omphalocele) – Figures 1, 2 and 3. Unfortunately, the patient had no first-trimester obstetrical care. The ultrasound evaluation confirmed the omphalocele and, in addition, the fetal sex was declared ambiguous. The ultrasound images revealed a possible bifid scrotum, yet there was an inability for better visualization of the penis (Figure 4). The couple’s current pregnancy was their first, and it is important to note that the pair is Caucasian, non-consanguineous and has no history of sexual strife in the family.

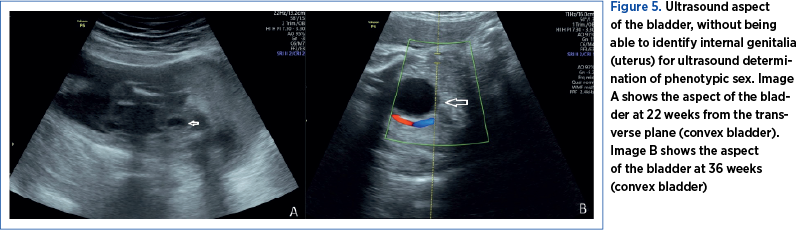

In most pregnancies, sonographic fetal sex determination is possible; nevertheless, in certain instances, it may present challenges. When determining the fetal sex in the late second trimester, sonographic methods rely on the direct view of the external genitalia. If external genitalia cannot be highlighted, the accurate identification of fetal sex may also be aided by other sonographic landmarks, such as the uterus, the descended testis, the fetal scrotum, the midline raphe of the penis, the labial lines, the uterus, and the direction and origin of the fetal micturition jet in males (Figure 5)(14).

The genetics results (screening for chromosome 13, 18 and 21 aneuploidies by QF-PCR from amniotic fluid and classic karyotype) confirmed a normal male fetal karyotype (46 XY) and no duplications or microdeletions of the 13, 18 or 21 chromosomes. Further investigations from the amniotic fluid, such as amniotic fluid testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels(15) and SRY gene(16), were not performed because of the high costs that the family could not afford.

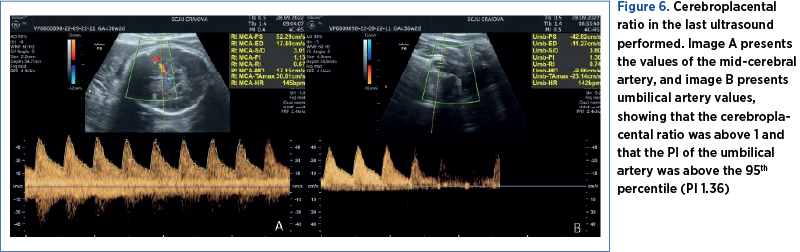

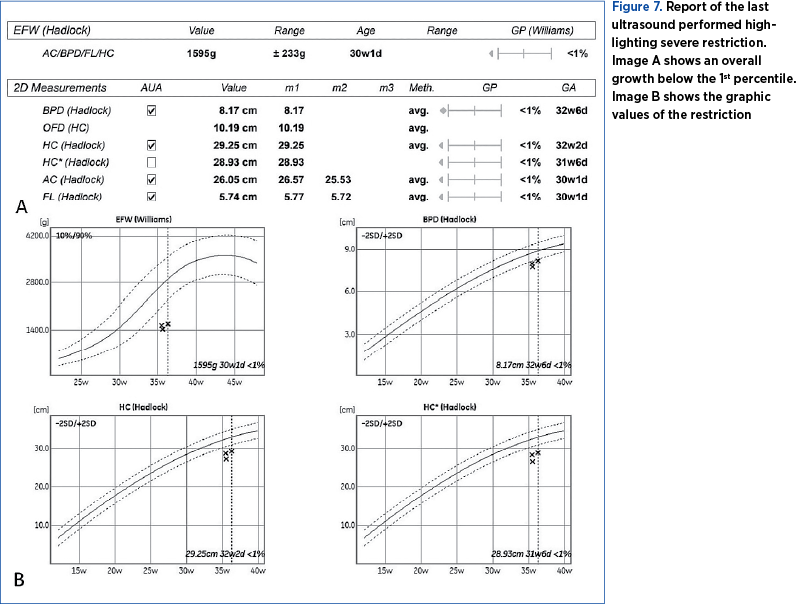

The pregnancy was monitored at the County Emergency Clinical Hospital of Craiova until 36 weeks and 2 days, when an elective caesarean section was performed due to the occurrence of intrauterine growth restriction and chronic fetal distress (Figures 6 and 7).

The postpartum diagnostic was omphalocele, micropenis with a stretched penile length of 1.4 cm, much lower than the average of 4 cm at birth(17) or under 2 cm(18), being able to be easily included in the micropenis spectrum, along with the bifid scrotum and hypospadias (Figure 8).

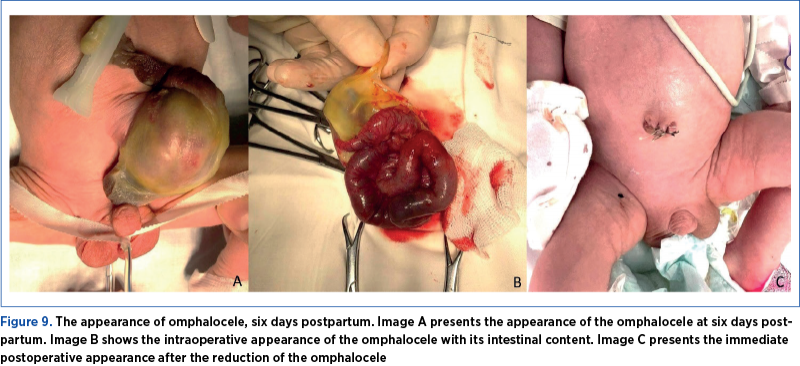

After six days of care in the newborn service, the patient was transferred to the pediatric surgery clinic, where he underwent omphalocele-reduction surgery (Figure 9). The short-term evolution was favorable, and the patient was discharged after two weeks.

Results

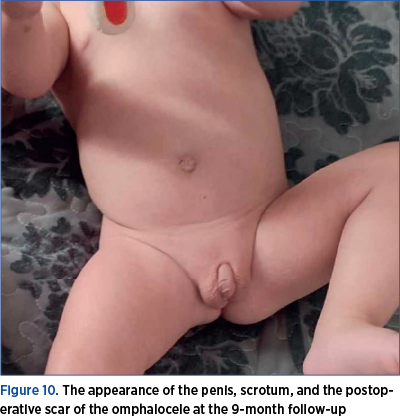

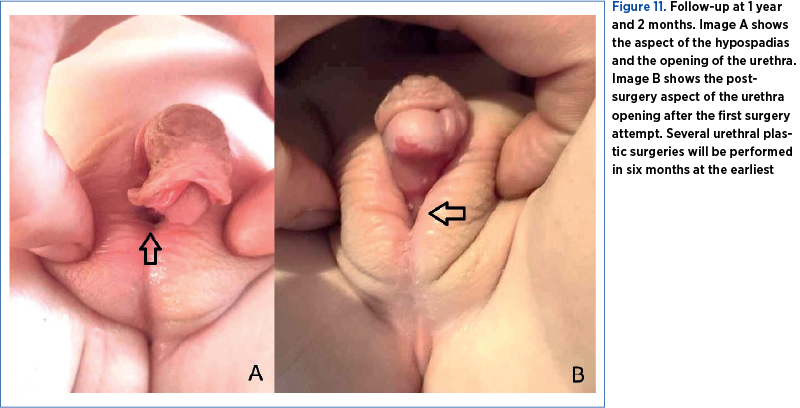

After the patient was discharged, the family continued the hormonal investigations. At the 9-month follow-up, the blood tests revealed a normal thyroid profile, the gonadotropic axis with prepubertal values, prolactin at the upper limit of normal, normal inhibin B, and normal corticotropic axis, but the testicles were not palpable in the scrotum (Figure 10). At 1 year and 2 months, the patient underwent the first hypospadias correction surgery (Figure 11).

Discussion

From what we have investigated so far, the micropenis, hypospadias, bifid scrotum and omphalocele, in our case, represented an isolated anomaly without other associated conditions. However, we know that omphalocele is associated with genetic abnormalities in 70% of cases(4,5). It is yet unknown, though, whether the presence of micropenis itself has any long-term effects regarding sexual satisfaction and life quality(19). Other studies found isolated micropenis, with no indication of gonadotrophin deficit or a fault in testosterone production, and no indication of a quantitative or qualitative failure in androgen binding. During a crucial stage of development, these isolated abnormalities may result from momentary errors in androgen production, action, or both(20). Bhangoo et al. (2010) discovered isolated micropenis with 5-reductase type 2 (SRD5A2) deficiency and AR gene abnormalities, both of which can cause androgen resistance(21). This study may not be applied to our case, but it is to be considered.

Regarding the omphalocele, studies have found that children with large omphalocele may experience delayed motor development; therefore, the advice was cautious observation and prompt referral to physical therapy for these kids(22). Trisomy 13, 18 or 21 and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome are the most prevalent chromosomal anomalies(23-25). However, in the case of our patient, the karyotype after the amniocentesis came out as normal.

Mulatinho et al. (2012) described a case with severe intellectual disability, omphalocele, hypospadias and high blood pressure. The genetic investigation found an interstitial deletion of 6 Mb in the long arm of the chromosome from 2q22.1 to 2q22.3(26). In our case, these anomalies do not seem to be part of a syndrome. Therefore, their association cannot be considered accidental, and microdeletions can be considered. Still, the microdeletions could not be investigated due to the significant costs of these investigations, not provided by the public medical healthcare system, and the lack of other symptoms after birth.

Ludorf et al. (2021) highlighted the fact that, out of 16,442 cases with hypospadias, 12.7% also presented other anomalies such as cardiac, musculoskeletal and additional urogenital defects(27).

Other studies presented the association between micropenis-hypospadias and omphalocele, but with the highlighting of several anomalies such as cryptorchidism, presacral dimple, flexion contractures of the fingers, bifid thumb, Simian crease, overriding toes, small for gestational age, hypoglycemia, ocular hypertelorism, microphthalmia, coloboma of the iris, low-set ears, beak nose and micrognathia(28). Our communication is the first to present this malformative association isolated, and not accompanied by other major structural or genetic abnormalities.

In the specialized literature, the association of micropenis, hypospadias, bifid scrotum and omphalocele, without other anomalies, is quite rare(29-31), which makes our case different from the rest of the literature.

Conclusions

Structural anomalies can often appear alone, spontaneously, or in association with other structural anomalies as part of syndromes. In our case, micropenis-hypospadias and omphalocele associations were found isolated, despite the detailed prenatal and postnatal evaluation and the literature findings. Fetal growth and well-being should be monitored, as intrauterine fetal growth restriction may occur.

Conflict of interest: none declared

Financial support: none declared

This work is permanently accessible online free of charge and published under the CC-BY.

Bibliografie

- Fisher R, Attah A, Partington A, Dykes E. Impact of antenatal diagnosis on incidence and prognosis in abdominal wall defects.

- J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(4):538–41.

- Yazbeck S, Ndoye M, Khan AH. Omphalocele: A 25-year experience.

- J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21(9):761–3.

- Verla MA, Style CC, Olutoye OO. Prenatal diagnosis and management of omphalocele. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28(2):84–8.

- Dunn JCY, Fonkalsrud EW. Improved survival of infants with omphalocele. Am J Surg. 1997;173(4):284–7.

- Akinkuotu AC, Sheikh F, Olutoye OO, Lee TC, Fernandes CJ, Welty SE, et al. Giant omphaloceles: surgical management and perinatal outcomes. J Surg Res. 2015;198(2):388–92.

- Baerg JE, Munoz AN. Long term complications and outcomes in omphalocele. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2019;28(2):118–21.

- Wiygul J, Palmer LS. Micropenis. Sci World J. 2011;11:1462–9.

- Kalfa N, Amouroux C, Fuchs F, Paris F. Should We Really Screen for Genital Variants Before Birth? Eur Urol. 2019;76(2):e39–40.

- Fuchs F, Borrego P, Amouroux C, Antoine B, Ollivier M, Faure J, et al. Prenatal imaging of genital defects: clinical spectrum and predictive factors for severe forms. BJU Int. 2019;124(5):876–82.

- Van Der Horst HJR, De Wall LL. Hypospadias, all there is to know. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(4):435–41.

- Fahmy MAB. Bifid Scrotum. In: Fahmy MAB (Editor). Normal and Abnormal Scrotum [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022 [cited 26 noiembrie 2023]. p. 187–203. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-83305-3_14

- Sharma D, Shastri S, Farahbakhsh N, Sharma P. Intrauterine growth restriction – part 1. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(24):3977–87.

- Peleg D, Kennedy CM, Hunter SK. Intrauterine growth restriction: identification and management. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(2):453–60, 466–7.

- Odeh M, Grinin V, Kais M, Ophir E, Bornstein J. Sonographic Fetal Sex Determination. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64(1):50–7.

- Mennuti MT, Wu CH, Mellman WJ, Mikhail G. Amniotic fluid testosterone and follicle stimulating hormone levels as indicators of fetal sex during mid-pregnancy. Am J Med Genet. 1977;1(2):211–6.

- Hawkins JR. The SRY gene. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1993;4(10):328–32.

- Schonfeld WA. Primary and secondary sexual characteristics: study of their development in males from birth through maturity, with biometric study of penis and testes. Am J Dis Child. 1943;65(4):535.

- Khadilkar V, Mondkar SA. Micropenis. Indian J Pediatr. 2023;90(6):598–604.

- Stancampiano MR, Suzuki K, O’Toole S, Russo G, Yamada G, Faisal Ahmed S. Congenital Micropenis: Etiology and Management. J Endocr Soc. 2022;6(2):bvab172.

- Evans BA, Williams DM, Hughes IA. Normal postnatal androgen production and action in isolated micropenis and isolated hypospadias. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66(9):1033–6.

- Bhangoo A, Paris F, Philibert P, Audran F, Ten S, Sultan C. Isolated micropenis reveals partial androgen insensitivity syndrome confirmed by molecular analysis. Asian J Androl. 2010;12(4):561–6.

- Hijkoop A, Peters NCJ, Lechner RL, Van Bever Y, Van Gils-Frijters APJM, Tibboel D, et al. Omphalocele: from diagnosis to growth and development at 2 years of age. Arch Dis Child - Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104(1):F18–23.

- Whitehouse JS, Gourlay DM, Masonbrink AR, Aiken JJ, Calkins CM, Sato TT, et al. Conservative management of giant omphalocele with topical povidone-iodine and its effect on thyroid function. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(6):1192–7.

- Lee SL, Beyer TD, Kim SS, Waldhausen JHT, Healey PJ, Sawin RS, et al. Initial nonoperative management and delayed closure for treatment of giant omphaloceles. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(11):1846–9.

- Zaccara A, Zama M, Trucchi A, Nahom A, De Stefano F, Bagolan P. Bipedicled skin flaps for reconstruction of the abdominal wall in newborn omphalocele. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(4):613–5.

- Mulatinho MV, De Carvalho Serao CL, Scalco F, Hardekopf D, Pekova S, Mrasek K, et al. Severe intellectual disability, omphalocele, hypospadia and high blood pressure associated to a deletion at 2q22.1q22.3: case report. Mol Cytogenet. 2012;5(1):30.

- Ludorf KL, Benjamin RH, Navarro Sanchez ML, McLean SD, Northrup H, Mitchell LE, et al. Patterns of co-occurring birth defects among infants with hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol. 2021;17(1):64.e1-64.e8.

- Chen H, Gershanik JJ, Mailhes JB, Sanusi ID. Omphalocele and partial trisomy 1q syndrome. Hum Genet. 1979;53(1):1–4.

- Zahouani T, Mendez MD. Omphalocele. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 [cited 28 October 2023]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519010/

- Mamatha K, Yelikar BR, Deshpande VR, Disha BS. A Rare Case of Genital Malformation with Omphalocele, Exstrophy of Bladder, Imperforate Anus and Spinal Defect Complex-Autopsy Findings. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(7):ED37-ED38.

- Al-Qurashi F, Al-Hareky T, Al-Buainain H. Omphalocele, exstrophy of bladder, imperforate anus and spinal defect complex with genital anomalies in a late preterm infant. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2017;5(1):67.