Gayet-Wernicke encephalopathy is an acute neuropsychiatric condition caused by thiamine deficiency. Only a small percentage of patients experience all three symptoms, with ophtalmoplegia, ataxia and confusion, and the full triad occurs more frequently among those who have overused alcohol. The evolution is toward full recovery, Korsakoff syndrome, dementia or death. We present the case of a 56-year-old patient, known with a diagnostic of alcoholism, who was admitted for a complicated withdrawal syndrome with delirium and who developed encephalopathy and dementia syndrome.

Evoluţie rapidă de la encefalopatie Gayet-Wernicke la demenţă, la un pacient cu dependenţă cronică alcoolică

Gayet-Wernicke encephalopathy with rapid evolution toward dementia in alcoholic dependence – case report

First published: 24 septembrie 2019

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.58.3.2019.2525

Abstract

Rezumat

Encefalopatia Gayet-Wernicke este o condiţie acută psihiatrico-neurologică, fiind cauzată de deficitul de tiamină. Doar un mic procent dintre pacienţi prezintă cele trei simptome principale (oftalmoplegie, ataxie şi confuzie), iar dintre aceştia, cei mai mulţi sunt pacienţi cu dependenţă cronică alcoolică. Evoluţia este spre recuperare completă, sindrom Korsakoff, demenţă sau deces. În lucrarea de faţă prezentăm cazul unui pacient de 56 de ani, cunoscut cu alcoolism cronic, care a fost internat pentru un sindrom de sevraj complicat cu delirium, cu evoluţie ulterioară spre encefalopatie şi demenţă.

Introduction

Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is an acute neuropsychiatric condition caused by depleted intracellular thiamine deficiency, most commonly arising in chronic alcohol misusers, who may present to emergency departments (EDs) for a variety of reasons(1). Other conditions causing malnutrition and decreased thiamine absorption, such as gastrointestinal surgical procedures (including bypass surgery, gastrojejunostomy, gastrectomy and colectomy)(2-7), therapy with intragastric balloon(8), chemical therapy(9,10), terminal tumor(11), anorexia nervosa(12), fasting(13), starvation(14), pancreatitis(15), and prolonged intravenous glucose infusion(16), have been reported as predisposing factors.

Clinically, the key features are mental status disturbances (global confusion), oculomotor abnormalities and gait disturbances (ataxia)(1). Apart from these clinical features, we can find deficits in neuropsychological functioning in patients with WE, which are more prominent after the improvement in the physical conditions. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, showing typical (thalami, mammilary bodies, tectal plate, and periaqueductal area) and atypical (cerebellum, cranial nerve nuclei, and cerebral cortex) signal-intensity alterations, is an essential tool to get the right diagnosis, especially when clinical presentation is incomplete(17). Although thiamine is the cornerstone of treatment of Wernicke’s encephalopathy, there are no universally accepted guidelines with regard to its optimal dose, mode of administration, frequency of administration or duration of treatment. The prognosis depends on prompt early intravenous administration of thiamine(1).

We present the case of a 56-year-old patient, known with a diagnostic of alcoholism, who was admitted for a complicated withdrawal syndrome with delirium and who developed encephalopathy and dementia syndrome.

Case report

A 56-year-old patient, with a 22-year history of alcohol abuse, was admitted to our hospital with acute confusional state, disorientation in time and space, tremor, sweating and complex visual hallucinations. He stopped the alcohol intake two days before hospitalization.

Patient history

Our patient was a non-smoker, married, with one son. The family members said that the patient functioned independently before the neurological problems and had no medical history, including psychiatric disorders. The amount of alcohol he consumed was 500 ml per day.

On admission: BMI – 20.3 kg/m2, with a body temperature of 37.7 oC, sweating, with a heart rate of 90/min, respiration of 18/min, and blood pressure of 130/85 mmHg, without clinical signs of heart or respiratory failure. He was drowsy, not oriented to person, place or time, with difficult speech, and not cooperative with the examination. There were no jaundice, or enlarged superficial lymph nodes observed. The abdomen was symmetrical, soft and without tenderness. The paraclinic workout showed hepatocytolysis.

Psychiatric evaluation

Face: hypomobile.

Perception: sensorial hypoestesia, visual hallucinations.

Attention: hypoprosexia.

Memory: hypomnesia.

Mood: irritability, irascibility.

Thinking: bradipsychia, no delusions.

Speech: difficult.

Behavior: tremor, psychomotor agitation, verbal and physical aggression.

Volition: hypobulia.

Consciousness: disorientation in time and space.

Sleep: insomnia.

Neurological evaluation

The neurological examination showed an agitated patient, in acute confusional state, sluggishly reactive pupils, without nistagmus, and with normal ocular movement, postural tremor of the upper limbs, decreased proprioception with absent deep tendon reflex in the lower limbs, without motor weakness or other sensory impairments, Babinski and Kerning signs were not present; with no other remarkable findings. All symptoms were characteristic for a complicated withdrawal syndrome with delirium.

Subsequently (one week after admission), the patient’s condition worsened, developing opisthotonus, bilateral mydriasis with slight reactive to light pupils, horizontal bilateral nystagmus, bilateral lateral rectus palsy, conjugate gaze palsy and gait ataxia, and he became unable to feed himself or to maintain the orthostatic posture. All symptoms were suggestive for a diagnosis of Gayet-Wernicke encephalopathy.

Electroencephalography revealed an encephalopathic pattern with diffuse slowing background activity with theta waves and some paroxysmal slow delta waves; the hyperventilation determined low-voltage and diffuse delta activity predominantly over the frontal brain regions (Figure 1).

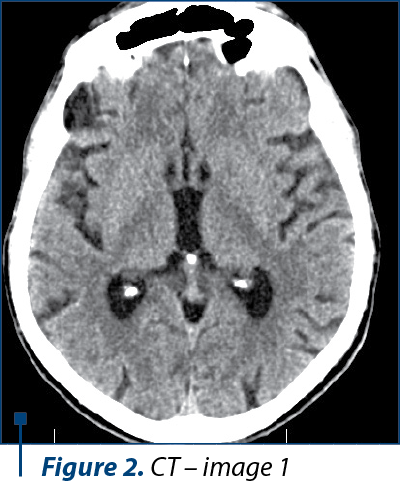

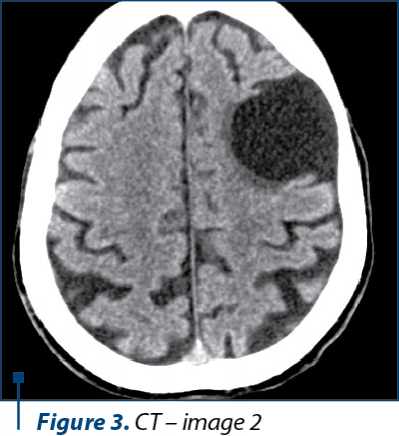

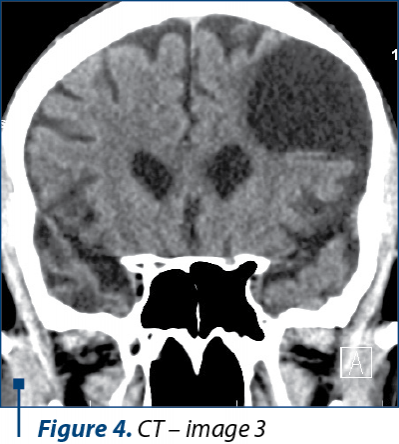

Because of his physical altered status, the patient was not able to perform an MRI. The CT scan examination revealed a cortico-subcortical cystic lesion of 43/38 mm in the left frontal lobe with minimal surrounding gliosis, most probably a porencephalic cyst, and old posttraumatic lesions on the right frontal lobe and on the anterior pole of the right temporal lobe, with no other pathological findings (Figure 2, 3, and 4).

At one month follow-up, after the administration of thiamine, the patient was confused, disorientated in time and space, agitated, with significant cognitive and behavioral impairment, emotional blunting, loss of insight, decline in personal hygiene, bilateral horizontal nystagmus and gait ataxia.

The psychological evaluation revealed: severe decline in attention, executive function, or visuo-spatial performance, disorientation in time and space. Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) = 4 points, Global Assessment of Functioning score (GAFS) = 10 points, Katz score for activities of daily living (ADL) = 1 (7) – severe dependence (low self-care), Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) – Lawton and Brody scale: 2 (8) – high dependency level, low self-maintenance. The clinical symptoms and the psychological evaluation were suggestive for a diagnosis of dementia.

Discussion

The patient in the present case report developed rapidly a Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) and a dementia syndrome with important cognitive, neuropsychiatric and functional impairments after the complicated withdrawal syndrome with delirium(18). The patient was able to function independently up to a point that he developed WE. The severity of the neuropsychiatric symptoms makes a patient in need of lifelong care.

In the present case, we were not able to perform an MRI because of the altered physical status of the patient, who was not able to cooperate for the investigation. We performed a CT scan, even though it is known that CT scans are not always sufficient for the imagistic diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy(19). The CT images were suggestive for an intense old blunt trauma of the head with most probably an impact point at the level of the left frontal region that caused a left frontal hematoma and a countercoup injury on the left frontal lobe and on the anterior pole of the temporal lobe. These images together with the rapid degradation of his neuropsychiatric status led us to believe that the patient could have had pugilistic dementia, but the family could not relate any recent or repetitive head trauma in the patient history and they admitted to the chronic alcohol abuse.

The characteristic lesions of Wernicke’s encephalopathy can be found at the level of both thalami, periaqueductal areas of the third ventricle, floor of the fourth ventricle, tectal area of the midbrain, cerebellar vermis and mammillary bodies – especially. These specific lesions have a low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images. CT scans images cannot reveal sustainable data about the structures situated in the posterior cranial fossa and the base of the brain, thus some Axial FLAIR and T2-weighted MRI images should have been obtain for revealing the characteristic lesions at the level of the mammillary bodies – if present.

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a medical emergency, and if not recognized and treated promptly, it is associated with progression to irreversible Korsakoff psychosis (consisting of confabulation and anterograde memory deficits), dementia or even death.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is often difficult, because of the clinical heterogeneity. The prognosis is very severe, leading to disabling persistent dysfunction and, in 20% of cases, to death. The proper management for rapid interventions in this life-threatening disorder involves complex teamwork, psychiatrists, neurologists, internal medicine specialists and appropriate medical imaging.

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments: We thank the patient and his family for their willingness to participate.

Bibliografie

- Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. The Lancet Neurology. 2007; 6(5), pp. 442-455.

- Singh S, Kumar A. Wernicke encephalopathy after obesity surgery: a systematic review. Neurology. 2007; 68(11), pp. 807-811.

- Loh Y, Watson WD, Verma A, Chang ST, Stocker DJ, Labutta RJ. Acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy following bariatric surgery: clinical course and MRI correlation. Obesity Surgery. 2014; 14(1), pp. 129-132.

- Becker DA, Ingala EE, Martinez-Lage M, Price RS, Galetta SL. Dry Beriberi and Wernicke’s encephalopathy following gastric lap band surgery. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2012; 19(7), pp. 1050-1052.

- Velasco MV, Casanova I, Sanchez-Pernaute A, et al. Unusual late-onset Wernicke’s encephalopathy following vertical banded gastroplasty. Obesity Surgery. 2009; 19(7), pp. 937-940.

- D’Abbico D, Praino S, Amoruso M, Notarnicola A, Margari A. Syndrome in syndrome: Wernicke syndrome due to afferent loop syndrome. Case report and review of the literature. Il Giornale di Chirurgia. 2011; 32(11-12), pp. 479-482.

- Nolli M, Barbier A, Pinna C, Pasetto A, Nicosia F. Wernicke’s encephalopathy in a malnourished surgical patient: clinical features and magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2005; 49(10), pp. 1566-1567.

- Chaves LC, Faintuch J, Kahwage S, deAssis Alencar F. A cluster of polyneuropathy and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in a bariatric unit. Obesity Surgery. 2002; 12(3), pp. 328-334.

- Cho IJ, Chang HJ, Lee KE, et al. A case of Wernicke’s encephalopathy following fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2009; 24(4), pp. 747-750.

- Turner JE, Alley JG, Sharpless NE. Medical problems in patients with malignancy: case 2. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: an unusual acute neurologic complication of lymphoma and its therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004; 22(19), pp. 4020-4022.

- Yae S, Okuno S, Onishi H, Kawanishi C. Development of Wernicke encephalopathy in a terminally ill cancer patient consuming an adequate diet: a case report and review of the literature. Palliative&Supportive Care. 2005; 3(4), pp. 333-335.

- Saad L, Silva LF, Banzato CE, Dantas C, Garcia C. Anorexia nervosa and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports. 2010; 4, article 217.

- Unlu E, Cakir B, Asil T. MRI findings of Wernicke encephalopathy revisited due to hunger strike. European Journal of Radiology. 2006; 57(1), pp. 43-53.

- Tsai HY, Yeh TL, Sheei-Meei W, Chen PS, Yang YK. Starvation-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy in schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2004; 58(3), pp. 338-339.

- Arana-Guajardo AC, Camara-Lemarroy CR, Rendon-Ramirez EJ, et al. Wernicke encephalopathy presenting in a patient with severe acute pancreatitis. Journal of Pancreas. 2012; 13(1), pp. 104-107.

- Koguchi K, Nakatsuji Y, Abe K, Sakoda S. Wernicke’s encephalopathy after glucose infusion. Neurology. 2004; 62(3), article 512.

- Manzo G, De Gennaro A, Cozzolino A, Serino A, Fenza G, Manto A. MR Imaging findings in alcoholic and nonalcoholic acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy: a review. BioMed Research International. 2014.

- Chotmongkol C, Limpawattana P. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: report of a case. J mEd Assoc Thailand. 2005; 88(6), pp. 855-858.

- Antunez E, Estruch R, Cardenal C, Nicolas JM, Fernandez-Sola J, Urbano-Marquez A. Usefulness of CT and MR imaging in the diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Am J Roentgenology. 1998; 171(4): 1131-1137.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Adicţiile în perspectiva pragmatică a ICD-11

Se inventariază modificările aduse de noua ediţie a ICD faţă de ediţia precedentă, precum şi în comparaţie cu predecesorul său temporal, DSM-5 (201...

Imagistica tensorului de difuzie și tractografia RMN – aplicaţii în maladia Alzheimer

Boala Alzheimer este cel mai frecvent întâlnit tip de demență la nivel global, prin urmare necesitatea diagnosticului precoce a devenit o prioritat...

Eficacitatea factorilor neurotrofici în tratamentul cazurilor cu demenţă mixtă, vasculară şi Alzheimer, cu multiple comorbidităţi

The incidence of neurodegenerative diseases has increased as a direct result of the increasing life expectancy.

Dificultăţi în diagnosticarea demenţei adultului tânăr – prezentare de caz

Demenţa frontotemporală (DFT) afectează în general adulţii cu vârste de 50-60 de ani, dar au fost raportate şi cazuri în jurul vârstei de 30 de ani...