Introduction. Now, the medical system represents one of the biggest fields in the global economy and is one of the most important factors for community development and for sustaining social well-being. Performance indicators of activity are essential instruments used for the management of the hospitals. They offer valid information that allows us to identify the weaknesses and strengths of the institutions and to improve the management performance.

Objectives. Talking about psychiatry, patients with the same main diagnostic, with the same treatment and duration of the hospitalization can present significant differences when looking at the complexity of the medical services and the resources that were needed. Therefore, a personalized approach adapted to the social particularities and to the functionality of the psychiatric patients is needed.

Methodology. This paper represents a review of the literature which is based on a series of scientific articles that have as a theme the activity indicators of hospitals, looking especially at the evaluation of the activity in a psychiatric hospital.

Results. Multiple studies have identified the following factors to be associated with psychiatric cases as predictors of using resources for the mental health: diagnostic stage of the illness, the severity of the symptoms, the risk of self-harm and aggressivity, the level of functioning socially and professionally, comorbidities, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Conclusions. The high management of a hospital needs a multidimensional approach, each medical field having its own particularities. Therefore, in psychiatry, the complexity indicators need an individual approach. Prospective payment for each case, based solely on the primary diagnostic and the number of hospitalization days, has proven to be superficial. A wrong evaluation of the human resources needed and of the materials for each case impaires the providing of high-quality medical services.

Redefinirea indicatorilor spitaliceşti pentru psihiatrie

Redefining hospital indicators for psychiatry

First published: 20 noiembrie 2021

Editorial Group: MEDICHUB MEDIA

DOI: 10.26416/Psih.67.4.2021.5712

Abstract

Rezumat

Introducere. În prezent, sistemele de sănătate reprezintă unul dintre cele mai mari sectoare ale economiei mondiale şi printre cei mai importanţi factori pentru dezvoltarea comunităţii şi asigurarea bunăstării sociale. Indicatorii de performanţă ai activităţii sunt instrumente esenţiale de management pentru spitale. Acestea oferă informaţii valide care să le permită să identifice punctele forte şi punctele slabe ale instituţiilor şi să îmbunătăţească performanţa managerială.

Obiective. În ceea ce priveşte psihiatria, pacienţii cu diagnostic principal, tratament şi durate ale spitalizării identice pot prezenta diferenţe semnificative în ceea ce priveşte complexitatea serviciilor medicale şi resursele implicate. Astfel, este necesară o abordare personalizată adaptată la particularităţile sociale şi de funcţionalitate ale pacienţilor cu tulburări psihice.

Metodologie. Lucrarea de faţă reprezintă un review de literatură care are la bază o serie de articole ştiinţifice ce au ca temă indicatorii de activitate ai spitalelor, cu accent pe evaluarea activităţii în cadrul spitalului de psihiatrie.

Rezultate. Mai multe studii au identificat următorii factori asociaţi cazurilor psihiatrice ca fiind predictori ai utilizării resurselor în sănătatea mintală: diagnosticul, stadiul bolii, severitatea simptomelor, riscul de autovătămare şi heteroagresivitate, nivelul de funcţionare socială şi profesională, comorbidităţile, caracteristicile sociodemografie.

Concluzii. Managementul performant al unui spital necesită o abordare multidimensională, fiecare specialitate având propriile particularităţi. Astfel, în psihiatrie, indicatorii de complexitate necesită o abordare individuală. Plata prospectivă pe caz, luând în considerare doar diagnosticul principal şi zilele de spitalizare, s-a dovedit a fi superficială. Evaluarea greşită a necesarului de resurse umane şi materiale în fiecare caz inhibă furnizarea unor servicii de îngrijiri medicale superioare.

Introduction

The medical system represents one of the biggest fields in the global economy and is one of the most important factors for community development and for sustaining the social well-being(1). In the World Health Report – Health Systems Financing, published by the World Health Organization (WHO), hospitals are identified as the main providers of medical services and among the factors that provide the most balanced distribution of the medical assistance and to promote the justice index for the medical field. Furthermore, healthcare systems accomplish intermediary and the final objectives at all the levels by improving the hospital performance(2). These are the main domains, but also the most expensive part of the healthcare system, so that in developed countries and in those that are developing, they represent 40% and 80% of the expenses in the medical field(3).

Hospitals are essential for the good working of the communities and most of the time they can represent a central point(4). Also, they are essential for healthcare systems, being instruments that have the role of coordinating the medical care system. They often provide an organized environment for education and formation of the doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals who work in the healthcare field and represent a critical basis for the clinical research. Hospitals should consider the needs and values of the community around them while also being resilient structures capable of providing healthcare services and adapting in emergency situations(5). An efficient hospital is conceived for beneficiaries, taking care of the needs of the population that is at risk, like children and elderly. A well-conceived hospital environment maximizes the efficiency of the given clinical aid and improves the well-being of the patients and of the healthcare workers.

A rapid increase in healthcare costs is directly proportional to the economic, social and cultural crisis confronting the healthcare system’s infrastructure(4,6). The aging of the population, the progress in the healthcare field and the development of the informational technology (telemedicine) represent changes that need more and more active and faster measures from the healthcare providers(7,8). The evaluation of the performance indicators of the hospitals is a type of strategy of management for those modifications. A continuous control of the procedures in the hospitals has as a goal the making of a proactive answer to those changes(9).

The performance indicators of activity are essential instruments of management for the hospitals. They offer viable information that allow us to identify the weak and the strong points of institutions and to improve the managerial performance(10). The complexity index of the cases (casemix) is a number without unit that expresses the resources that are needed by the hospital according to the number of patients treated (in Romania, this index is established according to the Minister of Health for approbation of the methodological norms for the application of the frame-contract), therefore those indexes of the complexity of cases become indexes of the performance of the hospitals.

Casemix systems were developed in the ‘70s by Robert B. Fetter of Yale University for the management of the patients who were admitted in the hospital in an acute regime(11). These represent a continuous system of learning that have as a central objective the improvement of the quality, efficiency and the transparency of the healthcare services that are delivered to the hospitals(12). Because these systems allow a classification of the patients who are in a hospital, in 1983, Health Care for All (HCFA) decided to use the system in the United States of America for financing the hospitals (for patients who had health insurance from HCFA, most of them beneficiaries of the Medicare program).

Once implemented in numerous politics of healthcare in the western world, multiple casemix systems were in continuous development, having to begin with either a system based on diagnostic groups, or other newer systems(13). The cornerstone of those systems remains the association of the patients in groups that are homogenous from the point of view of the utilisation of the resources(14,15). For realising a relevant prediction of the necessary resources for providing healthcare services, the casemix systems, despite their concept, need to capture and use the most important factors for determining the expenses. To describe a case in an adequate way in expenses, we need to consider the complexity of that case.

Regarding the patients who are hospitalised on the psychiatry wards, although with the same diagnostic and the same treatment, they can have significant differences regarding the complexity of the healthcare services required, differences determined by the degree of dysfunctionality, an indicator that is hard to quantify. The capacity of a casemix system to predict the use of the resources is realised in terms of proportions of variations explained by groups of diagnostics well defined(16). For centralisation of the calculated payments based on the casemix systems, payments made to the hospitals based on the real cost based on the needs of the healthcare services that are needed by the patient have been supported by research that examines the predictive power of different particularities among the characteristics of the patient considering the diagnostic and treatment(15,17,18). Therefore, it was argued that the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures alone don’t reflect adequately the differences that arise from the complexity, determining the elevation of the interest in the incorporation of some indicators of activity, such as the severity of the disease, comorbidities and risk factors(19-21). Therefore, the question remains if the actual casemix systems based on groups of diagnostics explain well enough the use of these resources, the cost of the healthcare of a patient, or the duration of the hospitalization(22).

Materials and method

This paper represents a review of the literature that is based on a series of scientific articles which have as a theme the activity indicators of hospitals, looking especially at the evaluation of the activity in a psychiatric hospital. The papers included were selected after research developed on the online data: PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Wiley Online. The citations in this paper are represented by clinical randomized studies, unsystematized reviews or meta-analytical studies.

Results

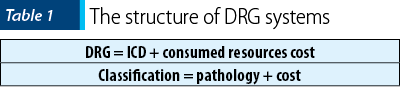

The evaluation of the Romanian hospitals is realized using the system of classification into basic diagnostic groups (Diagnosis-Related Groups – DRG basic), which represents, just like the name says, a schematic classification of the patients by the diagnostic. This represents a casemix system that is based on a structure that resembles the International Classification of Diseases – ICD, the diagnostics being classified in classes and subclasses. In addition to the ICD, in the DRG system they use the cost of the resources used for patient care as a classification criterion(23). In this way, through the DRG system, patients can be classified simultaneously by the pathology and by the cost of resources needed, which assures the possibility of associating the types of patients with the expenses of the hospital that have been made (Table 1).

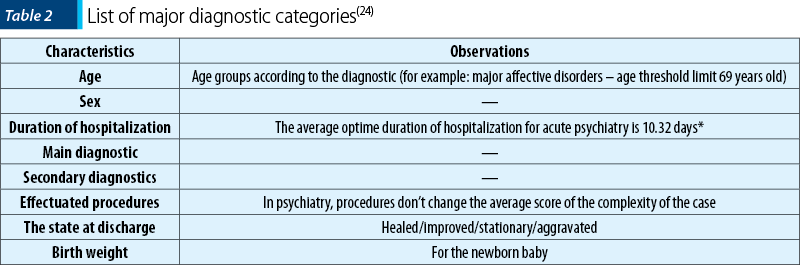

According to the casemix system used in Romania, the funding of the hospital wards, despite their profile, is based on the calculation of the average costs that is characterised for each discharged patient (Table 2).

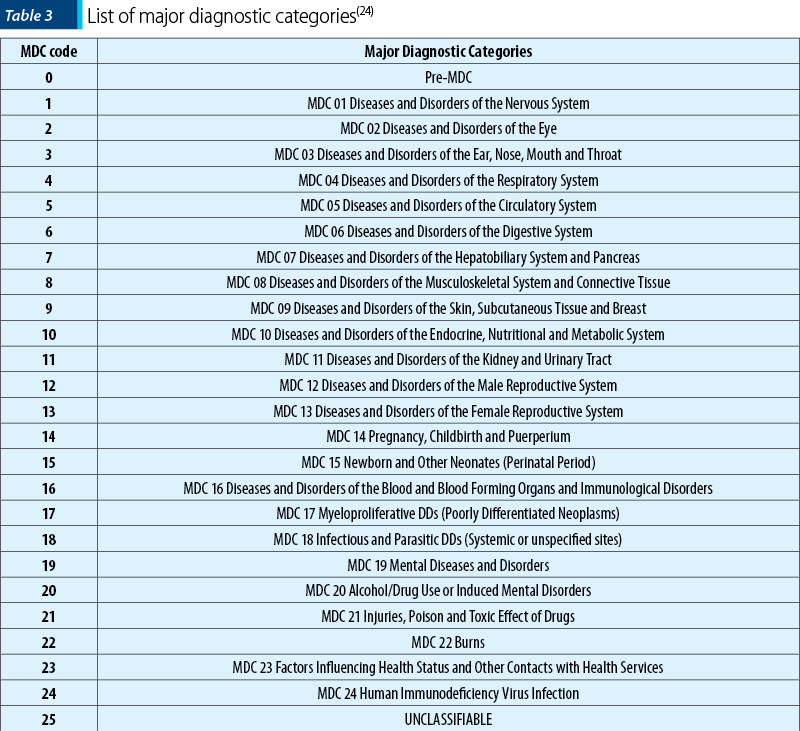

This represents a standardized method that is based on the description of the healthcare services in the form of average cost that is represented by the needing of the human and material resources (for example, a specific set of healthcare services given by a hospital to a patient with a certain pathology). The most known casemix system and widely used is the Diagnostic-Related Groups (DRGs), that groups mainly the potential patients hospitalised based on a predefined variable, the patient characteristics, such as demographic data (age, sex), main diagnostic and secondary diagnostics and procedures and therapeutic interventions in major diagnostic categories (MDC) – Table 3.

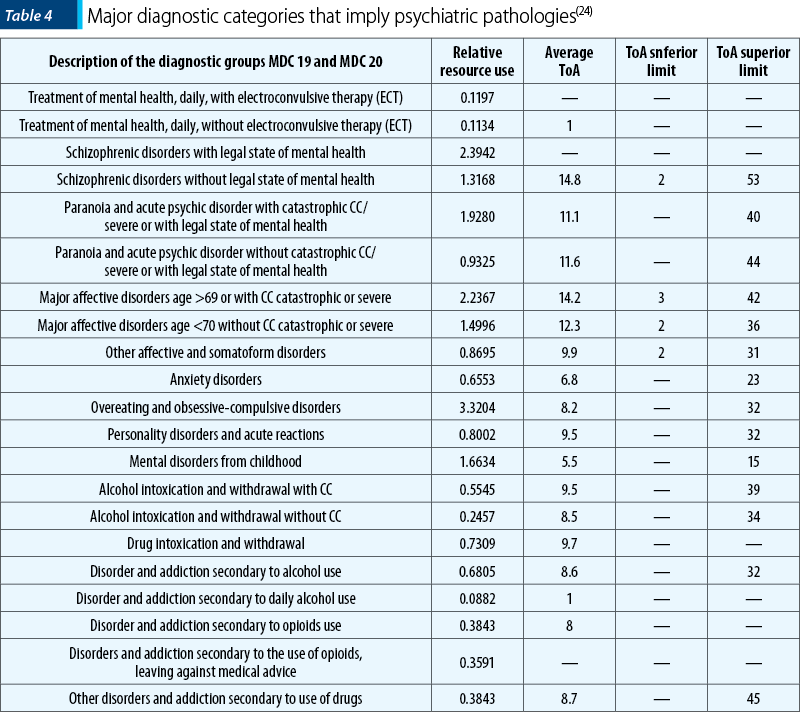

Regarding psychiatry, there are two major diagnostic categories involved: MDC 19 (Diseases and mental disorders) and MDC 20 (Alcohol/drug abuse and alcohol-induced organic mental disorders). These are detailed in Table 4, next to the relative DRG value, the time of admission (TA), and the inferior and superior limits of the duration of hospitalization.

The diagnostic groups are conceived for the purpose of standardization of the hospital’s efficiency; therefore, the results are expressed in the form of the number of patients discharged, homogenized within those predefined groups of diagnostics. Therefore, this public health policy determines healthcare systems to go in the opposite direction of the concept “there are no diseases, but sick people”(20,25).

The financing of the hospitals made by the DRG system assumes that every discharged patient will be included in a group of diagnostics that have prospectively established a cost for each resolved case, that will be paid to the hospital, despite the level of resources consumed with that patient(12). From this moment on, we can say that they will intervene over the big picture of the whole hospital because hospitals will change their activities to achieve services that will bring them a better income. For using the DRG system to finance hospitals, once the patients are classified in DRGs, there are two more steps needed(14):

a) Establishing the costs for each group of diagnostics (or relative values of the costs); those costs must be based on adjacent costs for each patient from a certain group of diagnostics, and they can be implemented at the same time as the classification system DRG or they can be developed for each country. Once the average cost for resolving a case for each DRG is calculated, those are transformed into payments and used for all the hospitals that participate in the system.

b) Giving the budget allocated for healthcare assistance for the hospitals, starting from the number and the type of patients discharged (the casemix of each hospital) and a list of costs (or relative values) for each DRG.

The financing with DRG can be made retrospectively (the reimbursement of the hospital for each type of discharged patient), or prospectively (establishing a global budget made by the negotiation of the number and the type of patients who will be hospitalized). Choosing one of those options depends on the way the share of the financial risk is made between the financier and the hospital(26).

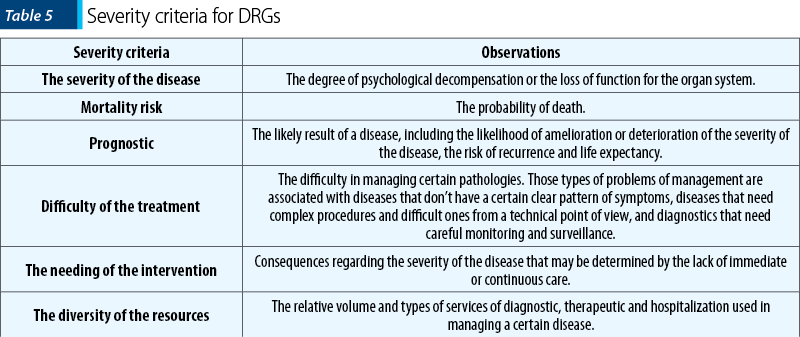

Currently, there are three versions of the DRG: basic DRGs, All Patient DRGs, and All Patient Refined DRGs. According to this classification, the definition of the severity of each case is realized by evaluating six dimensions (Table 5)(25).

Regarding the casemix systems, there are a series of preconceptions that lead to a lack of interest from healthcare professionals(16). First, it needs to be mentioned that these systems don’t have the purpose of reducing the quality of healthcare. Casemix systems represent instruments that can be used to analyze the ratio between quality and cost of the public healthcare systems. On the other hand, those systems don’t represent ways of payment, but are instruments that can be used for this purpose. Regarding their variety, there is not just the DRG system, but there are over 100 systems of casemix classification(28).

A meta-analytical study from 2014 which included 23 papers identified a total of 218 indicators that are utilized in the specialty literature. The average duration of stay in the hospital and the holding ratio of the bed have been most frequently used for evaluating the performance of the hospital. The evaluators were interested mainly in quantitative indicators for evaluating the performance of the hospital. The authors recommend that hospital managers select a combination of quantitative and qualitative indicators for monitoring performance in the medical field(29).

In 2018, Pourmohammadi et al. included a total of 49 scientific studies for the purpose of realizing a systematic review that had as its objective the evaluation of the main performance indicators of the hospital’s activity(1). The final model included three big categories of indicators: of productivity, of efficacy and financial. Human resources, the number of hospital beds, direct costs, the productivity of the operating room, the emergency room, the intensive care units, the radiology department, the laboratories and the productivity of technology and equipment are all included in the productivity indicators category. Regarding the efficacy indicators, those were classified as: seeing accessibility (equity), safety, quality, and responsibility. The responsibility indicators were classified in three big categories focused on: the patient, the medical staff, and the social role. Financial indicators included profitability, incomes, costs, active investments, debt, and liquidity.

The DRG type of casemix system has numerous limitations in many areas of expertise: mental healthcare, medical recovery, chronical diseases, palliative care, intensive therapy, neonatology(21,30-32). Worldwide, mental healthcare services are confronted with a rise in addressability and a lowering of resources. Therefore, the attention is focused on the cost of the care and the financial services that assure that the resources are appropriately matched to the needs. When the Prospective Payment System (PPS) Medicare was implemented for hospitals in 1983, the psychiatric care that was given in the psychiatric hospitals and in the liaison psychiatry of the general hospitals was exempt due to the concern that the diagnostic groups (DRG) would not be adequate because of the psychiatric cases(33). Further research did not sustain the prospective payment for each case (on the discharge), because they did not manage to make a system of classification of the patients that was efficient in explaining the variation in costs in psychiatric cases.

An article by Lave mentions two key reasons for the limited success in trying to identify the main characteristics of the costs in mental healthcare. Firstly, most of the systems were based on the diagnostic as a primary variable in classification, because it is viable in the administrative data, and the diagnostic had little to do with the cost of psychiatric care compared with the unviable factors in the administrative data. Secondly, it is difficult to measure the treatment costs of patients because the routine costs (mainly medical assistance and other services of social assistance offered in a hospital or unity with a psychiatric profile) represent a large portion of the total psychiatric costs. According to the convention report of costs (Medicare), all the patients from a certain facility have the same daily routine. As a result, the characteristics of the patients will explain the variation in the cost only to the extent that those variations evaluate just the identifiable characteristics, like age and sex(34).

Several studies have found that the following factors associated with psychiatric cases predict the use of mental health resources: diagnostic, disease stage, severity of symptoms, risk of self-harm and aggressivity, level of functioning socially and professionally, comorbidities and sociodemographic characteristics(28,35).

A study made by the Freiburg University in 2016, that followed-up 667 discharges of a psychiatric hospital, identified 25 variables in the prediction of the daily costs. The absolute value of the importance is neither informative, nor comparable with other studies. In exchange for that, they are supposed to be used to compare the relative importance of the variables that make up the subject of the investigation. The most important variable found was the global evaluation of the functionality (GAF), followed by deliriant symptoms, redirecting from a hospital to another and neurotic disorders as the main diagnostic. An accentuated lowering of importance was found after the first 10 variables. After that, there were differences of smaller importance between the variables(36).

In 2013, a team from Queensland University in Australia elaborated an alternative to the current DRG system, the MH-CASCC (Mental Health Classification and Service Cost Classification)(37). This is based on the calculation of the complexity index additionally to the casemix systems (diagnostic, severity, clinical variables and sociodemographic variables), the level of functionality, measured by a profile changed by life abilities (adults) or specific measures for children/adolescents.

Conclusions

In general, the performant management of a hospital requires a multidimensional approach, with each field having its own particularities. The evaluation of a limited and rigid number of indicators of the activity of all the hospital units may lead to an incorrect elaboration of a policy and of a public health decision.

Simultaneously, the diversity of the indicators from the specialized literature highlights the complexity of the application field and of the ways under which the performance of a hospital can be evaluated. A broad and complete approach to the system of evaluation of performance is conditioned by selecting the best-matched indicators in the first step.

Regarding the indicators of complexity of the case on a psychiatry ward, the prospective payment lowers the providing of some services of superior psychiatric healthcare. The DRG system provides a strong stimulant to reduce the duration of the hospitalization by imposing an optimal duration of treatment, which does not always correspond with the time when the psychotropic treatment begins to act.

Bibliografie

WHO. The World Health Report Health Systems Financing The path to iniversal coverage. The World Health Report, 2010.

Bastani P, Vatankhah S, Salehi M. Performance ratio analysis: A national study on Iranian hospitals affiliated to ministry of health and medical education. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2013 Aug; 42(8): 876–882.

McKee M, Healy J. The role of the hospital in a changing environment. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78(6):803-10. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0042-96862000000600012.

Turner BS. Hospital. Theory, Culture & Society. 2006 May;23(2-3):573-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276406023002136.

Abdulsalam Y, Schneller E. Hospital Supply Expenses: An Important Ingredient in Health Services Research. Medical Care Research and Review. 2019 Apr;76(2):240-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558717719928.

Bardhan IR, Thouin MF. Health information technology and its impact on the quality and cost of healthcare delivery. Decision Support Systems. 2013;55(2):438-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.10.003.

Steinman M, Morbeck RA, Pires PV, Abreu Filho CA, Andrade AH, Terra JC, Teixeira Junior JC, Kanamura AH, et al. Impact of telemedicine in hospital culture and its consequences on quality of care and safety. Einstein (São Paulo, Brazil). 2015 Oct-Dec;13(4):580-6. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-45082015GS2893.

Association AH. Fast facts on US hospitals. Internet URL (http://www Aha Org/Aha/Resource). 2012.

Hopfe M, Stucki G, Marshall R, Twomey CD, Üstün TB, Prodinger B. Capturing patients’ needs in casemix: A systematic literature review on the value of adding functioning information in reimbursement systems. BMC Health Services Research. 2016 Feb 3;16:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1277-x.

Fetter RB, Shin Y, Freeman JL, Averill RF, Thompson JD. Case mix definition by diagnosis-related groups. Medical Care. 1980 Feb;18(2 Suppl):iii, 1-53.

Quentin W, Geissler A, Scheller-Kreinsen D, Busse R. Understanding DRGs and DRG-based hospital payment in Europe. Diagnosis-Related Groups in Europe: Moving towards Transparency, Efficiency and Quality in Hospitals. Open University Press and Mc Graw Hill: Berkshire, England 2011.

Turner-Stokes L, Sutch S, Dredge R, Eagar K. International casemix and funding models: Lessons for rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2012 Mar;26(3):195-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511417468.

Fetter RB. Casemix classification systems. Australian Health Review: A Publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 1999;22(2):16-34; discussion 35-8. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH990016.

Street A, Kobel C, Renaud T, Thuilliez J. How well do diagnosis-related groups explain variations in costs or length of stay among patients and across hospitals? Methods for analysing routine patient data. Health Economics (United Kingdom). 2012 Aug;21 Suppl 2:6-18. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2837.

Averill R, Muldoon J, Vertrees L, et al. The Evolution of Casemix Measurement Using Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs). HIS Research Report. 1998.

Campbell SE, Seymour DG, Primrose WR, Almazan C, Arino S, Dunstan E, et al. A systematic literature review of factors affecting outcome in older medical patients admitted to hospital. Age and Ageing. 2004 Mar;33(2):110-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh036.

McCrone P. Predicting mental health service use: Diagnosis based systems and alternatives. Journal of Mental Health. 1995;4(1):31-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638239550037820.

Edwards N, Honemann D, Burley D, Navarro M. Refinement of the Medicare diagnosis-related groups to incorporate a measure of severity. Health Care Financing Review. 1994 Winter;16(2):45-64.

Horn SD, Horn RA, Sharkey PD, Chambers AF. Severity of illness within DRGs. Homogeneity study. Medical Care. 1986 Mar;24(3):225-35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198603000-00005.

Lichtig LK, Knauf RA, Bartoletti A, Wozniak LM, Gregg RH, Muldoon J, et al. Revising diagnosis-related groups for neonates. Pediatrics. 1989 Jul;84(1):49-61.

Forthman MT, Dove HG, Forthman CL, Henderson RD. Beyond Severity of Illness: Evaluating Differences in Patient Intensity and Complexity for Valid Assessment of Medical Practice Pattern Variation. Managed Care Quarterly. 2005;13(4).

Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, Bonazelli J, McCullough EC, Steinbeck B, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs): Methodology Overview. 3M Health Information Systems, 2003.

Geissler A, Scheller-Kreinsen D, Quentin W. Do diagnosis-related groups appropriately explain variations in costs and length of stay of hip replacement? A comparative assessment of DRG systems across 10 European countries. Health Economics (United Kingdom). 2012 Aug;21 Suppl 2:103-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2848.

Burgess P, Coombs T, Clarke A, Dickson R, Pirkis J. Achievements in mental health outcome measurement in Australia: Reflections on progress made by the Australian Mental Health Outcomes and Classification Network (AMHOCN). International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2012 May 28;6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-6-4.

Rahimi H, Khammar-Nia M, Kavosi Z, Eslahi M. Indicators of Hospital Performance Evaluation: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Hospital Research. 2014;3(4):199-208.

Smyth T. Safety and quality. Australian Health Review: A Publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2002;25(5):78-87. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH020078a.

Stevens VG, Hibbert CL, Edbrooke DL. Evaluation of proposed casemix criteria as a basis for costing patients in the adult general intensive care unit. Anaesthesia. 1998 Oct;53(10):944-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00576.x.

Guo P, Dzingina M, Firth AM, Davies JM, Douiri A, O’Brien SM, et al. Development and validation of a casemix classification to predict costs of specialist palliative care provision across inpatient hospice, hospital and community settings in the UK: A study protocol. BMJ Open. 2018 Mar 17;8(3):e020071. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020071.

Cotterill PG, Thomas FG. Prospective payment for Medicare inpatient psychiatric care: Assessing the alternatives. Health Care Financing Review. 2004 Fall;26(1):85-101.

Lave JR. Developing a Medicare prospective payment system for inpatient psychiatric care. Health Affairs. 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):97-109. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.22.5.97.

Eagar K, Gaines P, Burgess P, Green J, Bower A, Buckingham B, et al. Developing a New Zealand casemix classification for mental health services. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA). 2004 Oct; 3(3): 172–177.

Wolff J, McCrone P, Patel A, Normann C. Determinants of per diem hospital costs in mental health. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 31;11(3):e0152669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152669.

Eagar K, Green J, Lago L, Blanchard M, Diminic S, Harris M. Cost Drivers and a Recommended Framework for Mental Health Classification Development Final report for Stage B of the Definition and Cost Drivers for Mental Health Services project. Volume 1. University of Queensland. 2013;1:1–136.

Articole din ediţiile anterioare

Nu tot ceea ce strălucește este aur

Psihiatria comunitară din România a fost dezvoltată și reglementată prin Actul Regulator din anul 1974. Acesta a reprezentat un concept avansat, la...

Adresabilitatea către serviciile spitaliceşti de psihiatrie în timpul pandemiei de COVID-19 din România

Distribuţia în cele patru macroregiuni ale României a resurselor umane şi a capacităţilor instituţionale de internare pentru tratamentul tulburăril...

Modele patogenice diferenţiate implicate în evoluţia defavorabilă a schizofreniei

Schizofrenia este considerată, pe bună dreptate, cea mai severă tulburare psihiatrică, în care rezultatele terapeutice sunt încă sub aşteptările pr...

Spitalul de Psihiatrie Voila - Câmpina – studiu de caz

În contextul economico-social şi legislativ de astăzi, managerul unui spital de psihiatrie are, dincolo de atribuţiile și obligaţiile din contractu...