Actualităţi în diagnosticul hepatitei autoimune la copil

Update on the diagnosis of pediatric autoimmune hepatitis

Abstract

The types of autoimmune liver disorders recognized in the pediatric population are: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC), and de novo AIH after liver transplant. AIH can present with a broad clinical spectrum, specifically acute or severe acute hepatitis and chronic hepatitis. The diagnosis of AIH is based on clinical aspects, the laboratory investigations comprising liver and immunology analysis, and in some cases liver biopsy. AIH should be suspected after excluding other similar causes of liver disorders, such as viral hepatitis and metabolic disorders.Keywords

pediatric autoimmune hepatitisdiagnosisautoimmune sclerosing cholangitisautoantibodiesmagnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographyRezumat

Tipurile de boli hepatice autoimune recunoscute la populaţia pediatrică sunt: hepatita autoimună (AIH), colangita sclerozantă autoimună (ASC) şi AIH de novo după transplant hepatic. AIH prezintă un spectru clinic larg, ca hepatită acută, formă acută severă sau hepatită cronică. Diagnosticul AIH se bazează pe aspecte clinice, investigaţiile de laborator cuprinzând analize hepatice şi imunologice, iar în unele cazuri biopsie hepatică. AIH trebuie suspectată după excluderea altor cauze similare, cum ar fi hepatitele virale şi bolile metabolice.Cuvinte Cheie

hepatită autoimunăcopildiagnosticcolangită sclerozantă autoimunăautoanticorpicolangiopancreatografie prin rezonanţă magneticăIntroduction

The types of autoimmune liver disorders recognized in the pediatric population are autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC), and de novo AIH after liver transplant(1). AIH is a complex liver disease characterized by immune-mediated hepatocyte injury associated with the destruction of liver cells, causing inflammation, liver failure and fibrosis. AIH is an uncommon condition that affects all ages and all ethnicities. Some studies suggest that the incidence of pediatric AIH has been rising in the last two decades(2), while others consider that these cases are more often diagnosed compared to the past due to the increased awareness and the decrease in the number of cases of viral hepatitis after hepatitis B vaccination and hepatitis C effective treatment(1). AIH can present with a broad clinical spectrum, specifically acute(3) or severe acute hepatitis(4) and chronic hepatitis(5). The diagnosis of AIH is based on clinical aspects, the laboratory investigations comprising liver and immunology analysis, and in some cases liver biopsy. There are described two types of AIH that can be distinguished based on the serological profile: type 1 AIH (AIH-1) is positive for antinuclear antibody (ANA) and/or anti-smooth muscle antibody (SMA), and type 2 AIH (AIH-2) is defined by positivity for anti-liver kidney microsomal type 1 antibody (anti-LKM-1) and/or for anti-liver cytosol type 1 antibody (anti-LC-1). AIH should be suspected after excluding other similar causes of liver disorders, such as viral hepatitis and metabolic disorders(6). In the presence of a progressive inflammatory process, the continuous loss of hepatocytes can cause liver dysfunction and liver fibrosis in the long term(7).

Genetic trait

The mechanisms involved in autoimmune diseases represent a complex pathway between human leukocyte antigen (HLA) predisposing genes and non-HLA systems(8). The importance of HLA variants implicated in AIH-1 was demonstrated by a genome-wide association study (GWAS)(9). HLA genes responsible for AIH-1 susceptibility in adults are associated with the HLA-DRB1 variant on chromosome 6, representing a class II human major histocompatibility complex (MHC). The HLA-DR3 (DRB1*0301) and DR4 (DRB1*0401) molecules are described in North American and European populations(10,11), and the latest allele in Oriental populations(12). HLA genes responsible for AIH-1 susceptibility in children are associated with HLA-DR3 in northern Europe, but the DR4 encoding allele is not described as a genetic predisposition in pediatric AIH-1(13). The predisposition for AIH-2 is associated with HLA DRB1*0701(14) and DRB1*0301(15). There are multiple allele variants reported in AIH-1 susceptibility in different world areas, such as DRB1*1301 and DRB1*0301 in Brazil and Egypt(16), and also HLA-DRB1*1301 in South America(17). The susceptibility for AIH-2 in Egypt is described in the genetic variant HLA DRB1*15(16). In children with AIH-1 and AIH-2, a partial deficiency of the class III MHC complement component C4 was reported(18). In one-quarter of the cases, the autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) syndrome can be associated with AIH-2(19). A Danish nationwide registry analysis demonstrated the intricate relation between genetic and environmental factors, showing that in families with cases of AIH, first-degree relatives present a five-fold increased risk of developing AIH(20).

Clinical features and diagnosis

Specific features that can help establish the diagnosis of AIH are described: female preponderance(21), elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG), the presence of autoantibodies and histological findings that suggest interface hepatitis(22). The presence of ANA and/or SMA indicates AIH-1. In contrast, the presence of anti-LKM-1 and/or anti-LC-1 is attributed to AIH-2(23) (Table 1).

AIH-1 is described in both children and adults, while AIH-2 mainly affects children. There are little data based on the incidence of childhood AIH, but it is known that AIH type 1 accounts for approximately 60% of cases and appears most commonly in adolescents. In contrast, AIH-2 appears more frequently in younger children and infants(29). Presentation as fulminant hepatic failure, with elevated transaminase and bilirubin levels, is more often encountered in AIH-2 than in AIH-1(30). However, AIH-2 is more often refractory to treatment withdrawal(13).

Adult patients with AIH type 1 present a chronic course of the disease with symptoms such as abdominal and joint pain, nausea and fatigue(31), in comparison with juvenile AIH where children present with more severe wide-ranging symptoms, making the timing of diagnosis important, especially in prolonged severe liver disease. The diagnosis is often delayed in relapsing forms where awareness should be raised, and AIH should be excluded in the presence of sustained symptoms(1). The broad clinical spectrum can range from an acute presentation with nonspecific symptoms followed by jaundice, dark urine and pale stools (in almost half of the patients with both types)(27) to severe acute hepatitis with liver failure, developing encephalopathy in a period between two weeks and two months after presentation (3% of cases with AIH-1 and 25% of cases with AIH-2)(30). There is also described a slowly progressive course of disease in 40% of cases with AIH-1 and in 25% of cases with AIH-2, which can last for a period of a few months to a few years before diagnosis, characterized by malaise, headache, anorexia, weight loss, arthralgia, abdominal pain and relapsing jaundice(1). Only in rare asymptomatic cases, the diagnosis is based on an incidental finding of modified laboratory investigations(32). Approximately 10% of patients with both AIH types may present with end-stage liver disease and with symptoms of portal hypertension such as digestive bleeding and splenomegaly(28).

The presence of autoimmunity in the family is found in 40% of the cases. One-fifth of the patients present other overlapped autoimmune diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), nephrotic syndrome, thyroiditis, vitiligo, insulin-dependent diabetes(13), hemolytic anemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenia, celiac disease and urticaria pigmentosa(33). These disorders should be investigated in the presence of AIH, and immediate treatment should be conducted(34).

Among these, the most common disorders associated with AIH are autoimmune thyroiditis(33), celiac disease(35) and IBD(28). Recently, a study suggested that a gluten-free diet may have a positive long-term effect in patients with AIH and celiac disease. This statement was based on the differences between patients with AIH and celiac disease and those without celiac disease. These findings suggested that gluten withdrawal may strengthen the immunosuppressive treatment, resulting in sustained remission in the treatment-free period, reshaping the progression of AIH with overlapped celiac disease(36). This effect is compared with that seen in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and celiac disease with a gluten-free diet which displays an improved glycemic control due to enhanced gut permeability(37).

Addison disease and hypoparathyroidism are described most frequently in AIH-2 or autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal-dystrophy (APECED). APECED is an autosomal recessive genetic disease characterized by Addison disease, hypoparathyroidism and chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis(38). Some studies described multiple single-gene mutations that result in the association between immunodeficiency and autoimmunity, as well as AIH, based on an impaired immune system(39).

The diagnosis of AIH is based on clinical aspects, laboratory investigations comprising liver and immunology analysis, and in some cases liver biopsy. AIH should be suspected after excluding other similar causes of liver disorders such as drug-induced liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, viral hepatitis B, C and E, and Wilson disease(40). The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) proposed a diagnostic system that provides the probability of AIH using several positive and negative scores(41). Recently, simplified IAIHG criteria were suggested for being much easier to use in a clinical setting. The simplified score is based on IgG, autoantibodies, the histological examination, which forms the positive criteria, and the exclusion of other causes of hepatitis, such as hepatitis B, C or E viruses, Wilson disease or alcohol use, which form the negative criteria from the IAIHG score(22). Neither the original, nor the simplified scoring system is recommended in juvenile AIH, especially in the presence of severe acute hepatitis(42).

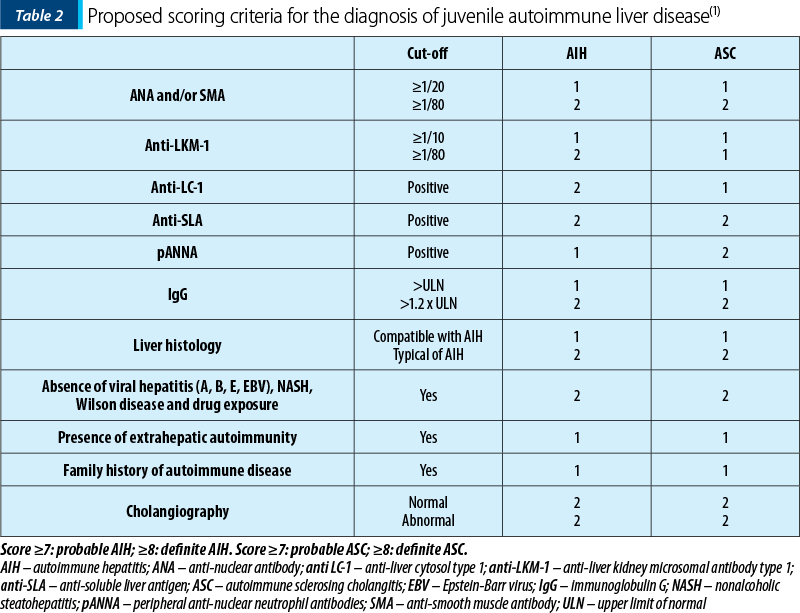

IAIHG cannot state the distinction between AIH and ASC. The difference between AIH and ASC can only be made by performing a cholangiogram that describes the bile duct disorder from disease onset(28). More recently, ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee published a Position Statement based on the diagnosis and management of juvenile AIH, proposing a diagnostic score to help differentiate between AIH and ASC(1) (Table 2).

ASC is a chronic disease characterized by intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic biliary tree inflammation, resulting in bile duct injury and liver fibrosis, with significant morbidity and mortality. Even though ASC was considered rare in children, the usage of noninvasive biliary imaging showed an increased frequency of ASC in the pediatric population, being as prevalent as AIH-1(28). Overlapping syndrome between AIH and ASC is more frequently described in children than in adults(1).

The clinical features of ASC, when compared to AIH, include: half of the patients with ASC are male; the common presenting symptoms in both ASC and AIH-1 are abdominal pain, jaundice and weight loss; IBD is encountered in almost half of children with ASC and in only 20% of those with AIH; all ASC patients have positive ANA and/or SMA and almost all have a significant increase in serum IgG levels; the presence of pANCA is described in two-thirds of children with ASC compared to half of the patients with AIH-1 and only 10% of those with AIH-2; standard liver function tests at presentation cannot differentiate between AIH and ASC.

In the early disease stages of ASC, alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels are usually normal or only slightly increased. This underlines the importance of performing a cholangiogram or a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography from the presentation. Despite abnormal images on cholangiograms, 25% of the patients with ASC have no bile duct involvement on histology, while 27% of the children with AIH have biliary disease on histology(1). Often, ASC is initially diagnosed and treated as AIH-1 and is discovered during follow-up only after the appearance of the cholestatic disease(28).

Laboratory investigations

The laboratory investigations reveal a wide range of abnormalities; among these, there are elevated transaminase values and impaired synthetic function in almost half of the patients, with low albumin levels and modified coagulation tests(28). Most of the patients have high IgG levels, but normal values of IgG do not exclude the diagnosis of AIH(13). The cut-off value of autoantibodies is lower in pediatric patients than in adults(43). One-quarter of the cases with AIH-2 and approximately 15% of those with AIH-1 have a normal level of IgG levels, especially in an acute clinical setting(1). There is described a reduction in the levels of IgG among these children after beginning the immunosuppressive treatment. Also, AIH-2 can have partial IgA deficiency more often than AIH-1(29).

The presence of antinuclear antibody (ANA) and/or anti-smooth muscle antibodies (SMA) indicates AIH type 1 (AIH-1), while the presence of anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody type 1 (LKM-1) and/or anti-liver cytosol type one antibody (LC-1) is attributed to AIH type 2 (AIH-2)(23). Some patients with hepatitis C can also have positive anti-LKM-1. Therefore, the exclusion of hepatitis C is mandatory before diagnosing AIH-2(44). Other autoantibodies that can be used include anti-soluble liver antigen (anti-SLA) and peripheral antinuclear neutrophil antibody (atypical pANCA or pANNA). pANCA is often observed in AIH-1 or ASC and IBD, whereas in AIH-2 it is absent(45). SMA can be used for monitoring treatment efficiency in children(46) and adults with AIH-1(47), while anti-LKM1 and anti-LC1 can be used in monitoring response to therapy in juvenile AIH-2(48).

Anti-SLA (autoantibodies to soluble liver antigen) were first characterized as specific for AIH type 3(49). Still, recently the development of these autoantibodies has been described in both types of AIH. Even though they were only found in a few cases of AIH, they are an indicator of disease severity with a higher number of relapses(50).

Histology

Almost one-third of the cases have cirrhosis on liver biopsy at the diagnostic moment, even those presenting with acute symptoms, therefore AIH should be suspected regardless of the mode of presentation(13). Liver biopsy in both types demonstrates a similar aspect regarding the severity of interface hepatitis, but in AIH-1 the initial biopsy describes more often cirrhosis than in type 2(28).

Liver biopsy in AIH shows: portal inflammatory infiltrate with dense mononuclear cells and plasma cells which extends into lobule; interface hepatitis displayed by damage in the outer layer of periportal hepatocytes; enhanced collagen synthesis resulting from hepatocyte destruction which extends from periportal space into the lobule; liver cells regeneration with “rosette” formation(51).

The severity of inflammation, hepatocyte destruction and the presence and extension of fibrosis are variable among cases. Liver biopsy can also demonstrate the presence of an overlapped nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or ASC. Interface hepatitis is not pathognomonic for AIH; it can also be encountered in other disorders and can be absent in cases with AIH which were previously treated with immunosuppressive medication(28). The relapse of AIH can include panlobular inflammatory infiltrate with periportal necrosis expanding to the centrilobular area, forming bridging necrosis(52).

Conclusions

The early diagnosis is important, but the currently used AIH scoring systems do not display sufficient sensitivity, and further firm diagnostic tools are still needed. There are guidelines that provide a fundamental overview about diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. This underlines the importance of distinguishing between AIH and other similar causes of liver disorders such as viral hepatitis, metabolic disorders, ASC and drug-induced liver disease. The prognosis of pediatric cases with AIH who are treated with immediate immunosuppressive treatment is favorable, with good long-term survival rates and a reduced effect on the quality of life.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliografie

-

Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Baumann U, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Autoimmune Liver Disease: ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee Position Statement. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(2):345-360.

-

Sebode M, Kloppenburg A, Aigner A, et al. Population-based study of autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cholangitis in Germany: rising prevalences based on ICD codes, yet deficits in medical treatment.

-

Z Gastroenterol. 2020;58(5):431-438.

-

Czaja AJ. Acute and acute severe (fulminant) autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(4):897-914.

-

Yasui S, Fujiwara K, Yonemitsu Y, et al. Clinicopathological features of severe and fulminant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(3):378-390.

-

Heneghan MA, Yeoman AD, Verma S, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis. Lancet (London, England). 2013;382(9902):1433-1444.

-

Corrigan M, Hirschfield GM, Oo YH, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis: an approach to disease understanding and management. Br Med Bull. 2015;114(1):181-191.

-

Czaja AJ. Hepatic inflammation and progressive liver fibrosis in chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(10):2515.

-

Seldin MF. The genetics of human autoimmune disease: A perspective on progress in the field and future directions. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:1-12.

-

de Boer YS, van Gerven NM, Zwiers A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants associated with autoimmune hepatitis type 1. Gastroenterology. 2014 Aug;147(2):443-52.e5.

-

Donaldson PT. Genetics in autoimmune hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22(4):353-363.

-

van Gerven NMF, de Boer YS, Zwiers A, et al. HLA-DRB1*03:01 and HLA-DRB1*04:01 modify the presentation and outcome in autoimmune hepatitis type-1. Genes Immun. 2015;16(4):247-252.

-

Furumoto Y, Asano T, Sugita T, et al. Evaluation of the role of HLA-DR antigens in Japanese type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15(1):1-9.

-

Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Reid F, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20-year experience. Hepatology. 1997;25(3):541-547.

-

Bittencourt PL, Goldberg AC, Cançado EL, et al. Different HLA profiles confer susceptibility to autoimmune hepatitis type 1 and 2. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(8):1394-1395.

-

Ma Y, Bogdanos DP, Hussain MJ, et al. Polyclonal T-cell responses to cytochrome P450IID6 are associated with disease activity in autoimmune hepatitis type 2. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):868-882.

-

Elfaramawy AA, Elhossiny RM, Abbas AA, et al. HLA-DRB1 as a risk factor in children with autoimmune hepatitis and its relation to hepatitis A infection. Ital J Pediatr. 2010 Nov 10;36:73.

-

Pando M, Larriba J, Fernandez GC, et al. Pediatric and adult forms of type I autoimmune hepatitis in Argentina: evidence for differential genetic predisposition. Hepatology. 1999;30(6):1374-1380.

-

Vergani D, Wells L, Larcher VF, et al. Genetically determined low C4: a predisposing factor to autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Lancet (London, England). 1985;2(8450):294-298.

-

Meloni A, Willcox N, Meager A, et al. Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome Type 1: An Extensive Longitudinal Study in Sardinian Patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(4):1114-1124.

-

Grønbæk L, Vilstrup H, Pedersen L, et al. Family occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis: A Danish nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):873-877.

-

Tenca A, Farkkila M, Jalanko H, et al. Environmental risk factors of pediatric-onset primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(3):437-442.

-

Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48(1):169-176.

-

Muratori P, Granito A, Quarneti C, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in Italy: the Bologna experience. J Hepatol. 2009;50(6):1210-1218.

-

Webb GJ, Hirschfield GM, Krawitt EL, et al. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2018;13:247-292.

-

Rodrigues AT, Liu PMF, Fagundes EDT, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis in Children and Adolescents with Autoimmune Hepatitis and Overlap Syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63(1):76-81.

-

Tanaka A, Takikawa H. Geoepidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a critical review. J Autoimmun. 2013;46:35-40.

-

Jiménez-Rivera C, Ling SC, Ahmed N, et al. Incidence and Characteristics of Autoimmune Hepatitis. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1237-e1248.

-

Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Karani J, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis/sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome in childhood: a 16-year prospective study. Hepatology. 2001;33(3):544-553.

-

Oettinger R, Brunnberg A, Gerner P, et al. Clinical features and biochemical data of Caucasian children at diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.

-

J Autoimmun. 2005;24(1):79-84.

-

Di Giorgio A, Bravi M, Bonanomi E, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure of autoimmune aetiology in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(2):159-164.

-

Al-Chalabi T, Underhill JA, Portmann BC, et al. Impact of gender on the long-term outcome and survival of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48(1):140-147.

-

Brissos J, Carrusca C, Correia M, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis: trust in transaminases. BMJ Case Rep. 2014; 2014: bcr2014203869.

-

Wong GW, Heneghan MA. Association of Extrahepatic Manifestations with Autoimmune Hepatitis. Dig Dis. 2015;33 Suppl 2:25-35.

-

Guo L, Zhou L, Zhang N, Deng B, et al. Extrahepatic Autoimmune Diseases in Patients with Autoimmune Liver Diseases: A Phenomenon Neglected by Gastroenterologists. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017; 2017:2376231.

-

Najafi M, Sadjadei N, Eftekhari K, et al. Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Children with Autoimmune Hepatitis and vice versa. Iran J Pediatr. 2014;24(6):723.

-

Nastasio S, Sciveres M, Riva S, et al. Celiac disease-associated autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: long-term response to treatment. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56(6):671-674.

-

Uibo R, Panarina M, Teesalu K, et al. Celiac disease in patients with type 1 diabetes: a condition with distinct changes in intestinal immunity? Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8(2):150.

-

Ahonen P, Myllärniemi S, Sipilä I, et al. Clinical variation of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) in a series of 68 patients. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(26):1829-1836.

-

Grimbacher B, Warnatz K, Yong PFK, et al. The crossroads of autoimmunity and immunodeficiency: Lessons from polygenic traits and monogenic defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(1):3-17.

-

Association for the Study of the Liver E. Corrigendum to “EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis”. J Hepatol. 2015;63(6):1543-1544.

-

Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.

-

J Hepatol. 1999;31(5):929-938.

-

Ferri PM, Ferreira AR, Miranda DM, et al. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune hepatitis in children: A challenge for pediatric hepatologists. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(33):4470.

-

Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi FB, et al. Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2004;41(4):677-683.

-

Lamireau T, McLin V, Nobili V, et al. A practical approach to the child with abnormal liver tests. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2014;38(3):259-262.

-

Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Mieli-Vergani G, et al. Serology in autoimmune hepatitis: A clinical-practice approach. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;48:35-43.

-

Gregorio GV, McFarlane B, Bracken P, et al. Organ and non-organ specific autoantibody titres and IgG levels as markers of disease activity: a longitudinal study in childhood autoimmune liver disease. Autoimmunity. 2002;35(8):515-519.

-

Couto CA, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, et al. Antismooth muscle and antiactin antibodies are indirect markers of histological and biochemical activity of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2014;59(2):592-600.

-

Muratori L, Cataleta M, Muratori P, et al. Liver/kidney microsomal antibody type 1 and liver cytosol antibody type 1 concentrations in type 2 autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 1998;42(5):721.

-

Manns M, Kyriatsoulis A, Gerken G, et al. Characterisation of a new subgroup of autoimmune chronic active hepatitis by autoantibodies against a soluble liver antigen. Lancet (London, England). 1987;1(8528):292-294.

-

Ma Y, Okamoto M, Thomas MG, et al. Antibodies to conformational epitopes of soluble liver antigen define a severe form of autoimmune liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35(3):658-664.

-

de Boer YS, van Nieuwkerk CMJ, Witte BI, et al. Assessment of the histopathological key features in autoimmune hepatitis. Histopathology. 2015;66(3):351-362.

-

Hegarty JE, Nouri Aria KT, Portmann B, et al. Relapse following treatment withdrawal in patients with autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1983;3(5):685-689.